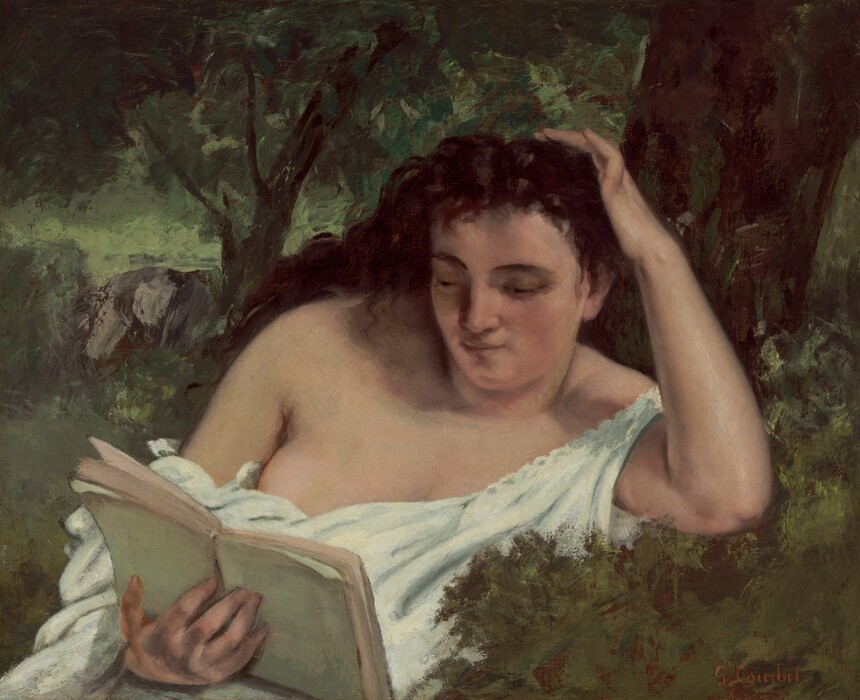

Gustave Courbet

Bibliography

1856

Silvestre, Théophile. Histoire des artistes vivants, français et étrangers. Paris, 1856: 211-277.

1878

Mantz, Paul. "Gustave Courbet." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 17 (1878): 514-527; 18 (1878): 17-29, 371-384.

d'Ideville, Henri. Gustave Courbet, notes et documents sur sa vie et son oeuvre. Paris, 1878.

1880

Gros-Kost, Emile. Gustave Courbet: Souvenirs intimes. Paris, 1880.

1882

Castagnary, Jules. Exposition des oeuvres de Gustave Courbet à l'Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Paris, 1882.

1897

Estignard, Alexandre. G. Courbet, sa vie et ses oeuvres. Besançon, 1897.

1906

Riat, Georges. Gustave Courbet, peintre. Paris, 1906.

1911

Castagnary, Jules. "Fragments d'un livre sur Courbet." Gazette des Beaux-Arts 4th ser., 5 (1911): 1-20; 6 (1911): 488-497; 7 (1912): 19-30.

1918

Duret, Theodore. Courbet. Paris, 1918.

1929

Léger, Charles. Courbet et son temps. Paris, 1925 (final edition: 1948).

1948

Courthion, Pierre. Courbet raconté par lui-même et par ses amis. 2 vols. Geneva, 1948.

1951

Mack, Gerstle. Gustave Courbet. London, 1951.

1973

Clark, Timothy J. Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution. London, 1973.

Nicolson, Benedict. Courbet: The Studio of the Painter. New York, 1973.

1977

Fernier 1977.

Toussaint, Hélène. Gustave Courbet (1819-1877). Exh. cat. Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 1977.

1978

Fernier, Robert. La Vie et l'oeuvre de Gustave Courbet, catalogue raisonné. Peintures, 1866-1877, dessins, sculptures. Paris, 1978.

1987

Mainardi, Patricia. Art and Politics of the Second Empire. London and New Haven, 1987.

1992

Chu, Petra Ten Doesschate. Letters of Gustave Courbet. Chicago and London, 1992.

2000

Eitner, Lorenz. French Paintings of the Nineteenth Century, Part I: Before Impressionism. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C., 2000: 102-105.