Language

On this Page:

Overview

How does Gordon Parks use photography to address inequities in the United States?

How do Gordon Parks’s images capture the intersections of art, race, class, and politics across the United States?

What do photographs in general—and Gordon Parks’s photographs more specifically—tell us about the American Dream?

“A photographer can be a storyteller. Images of experience captured on film, when put together like words, can weave tales of feeling and emotion as bold as literature.… [Photographers] bring together fact and fiction, experience, imagination, and feelings in a visual dialogue that has enormous impact on how we observe and relate to the external world and our internal selves.” —Philip Brookman, “Unlocked Doors: Gordon Parks at the Crossroads,” Gordon Parks: Half Past Autumn, 1997

What did you picture while reading this quote? Consider where you encounter photographs and images in your own life. What impact do they have on you?

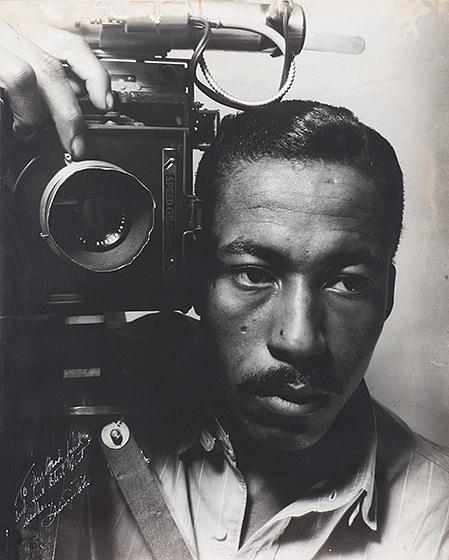

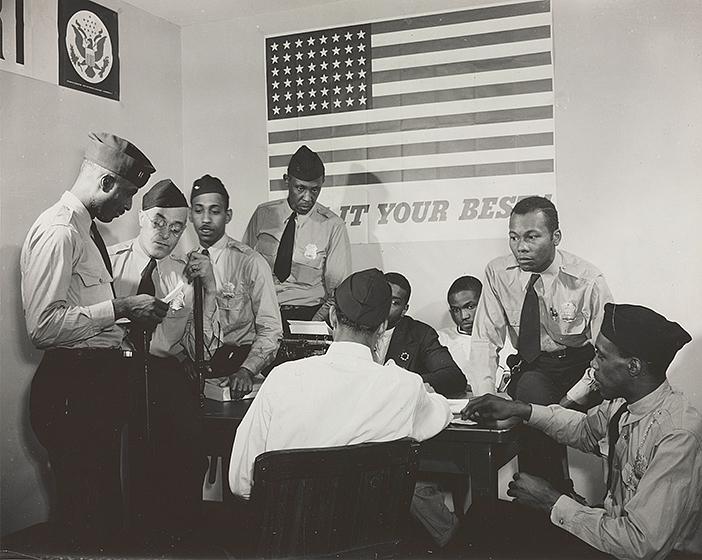

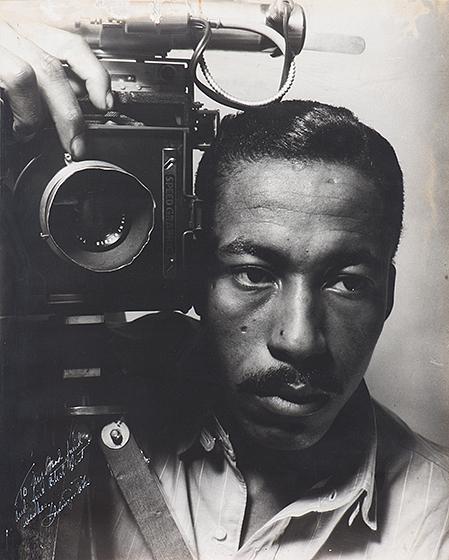

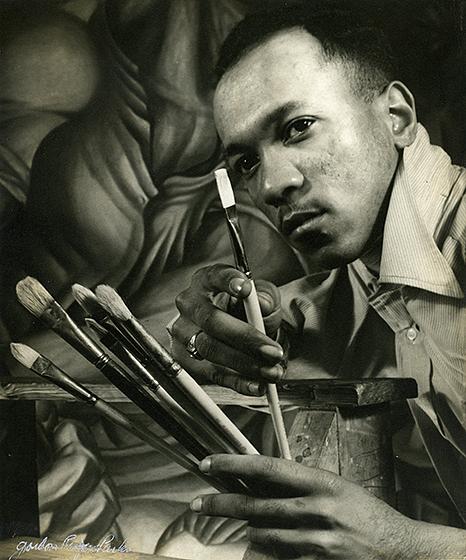

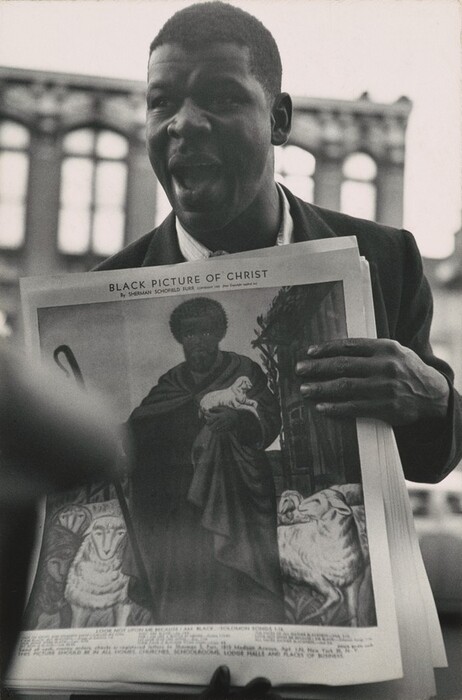

There is perhaps no individual who embodies the power of photography more than Gordon Parks. Photographer, poet, musician, storyteller, activist—Gordon Parks shaped the times in which he lived as much as he was shaped by them. Though his career as a photographer spanned six decades, it is the period from 1940 to 1950, the focus of the exhibition Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940–1950, that most significantly defined his point of view as an African American artist and documenter of American life at the dawn of the modern civil rights movement.

In 1937, while working as a waiter on the North Coast Limited passenger train, Parks saw magazines featuring Depression-era photographs—images like Dorothea Lange’s Migrant agricultural worker’s family, Nipomo, California that recorded the social and economic conditions of migrant farmers across the country. For Parks, images of dust bowl migrants reminded him of his own struggles and inspired him to purchase his first camera, a life-changing decision. He later recalled, “I was convinced of the power of a good picture.”

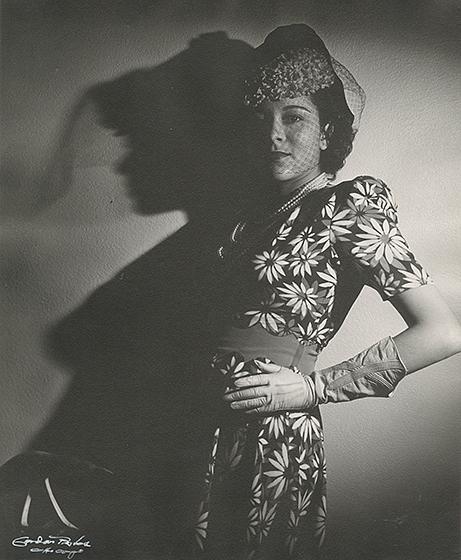

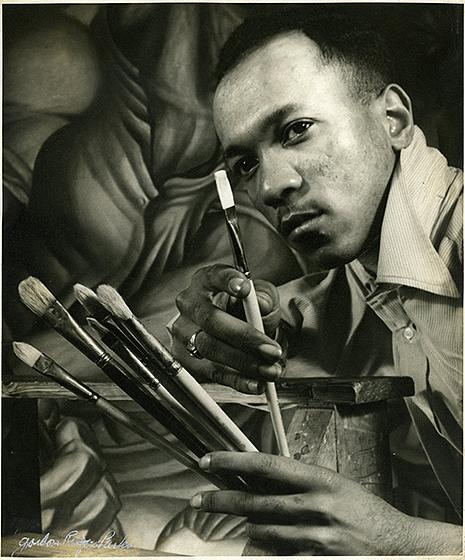

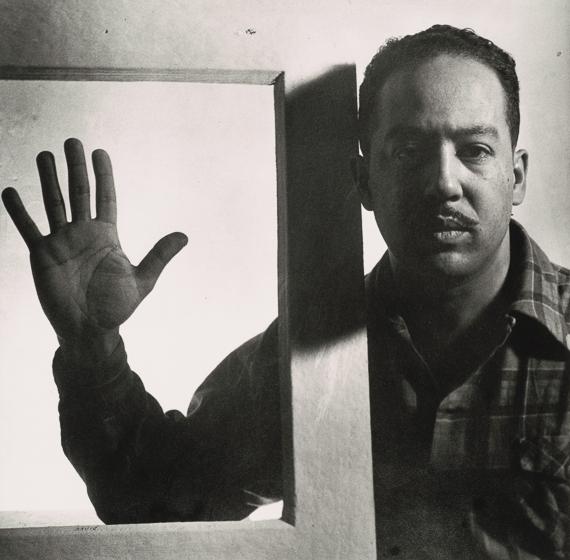

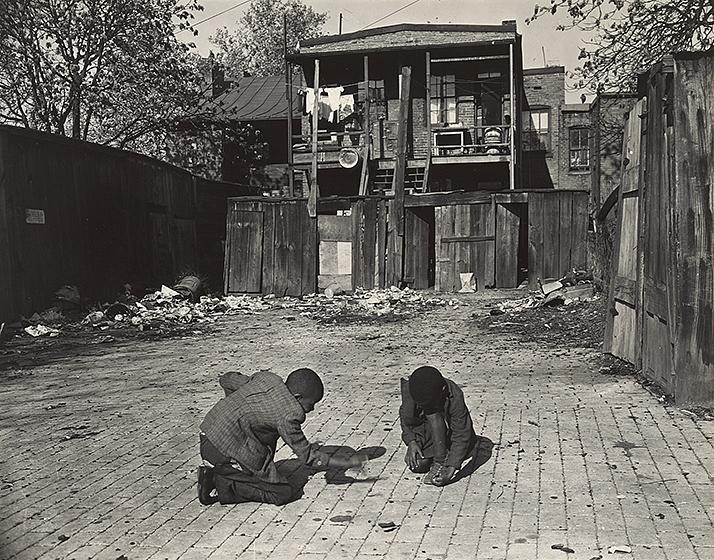

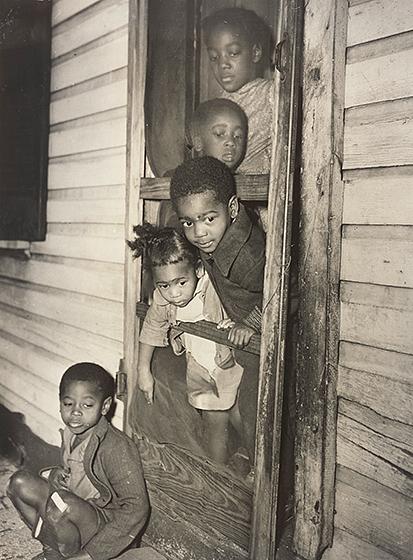

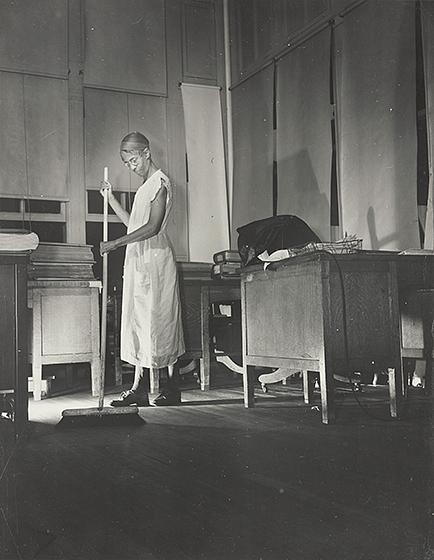

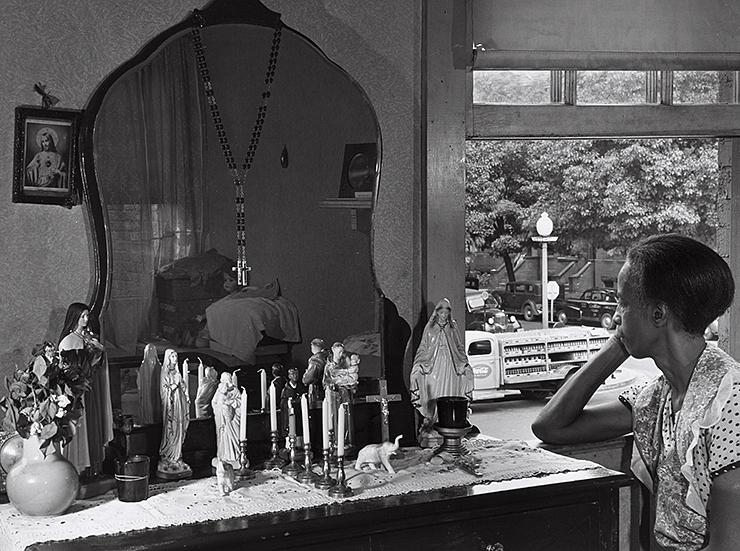

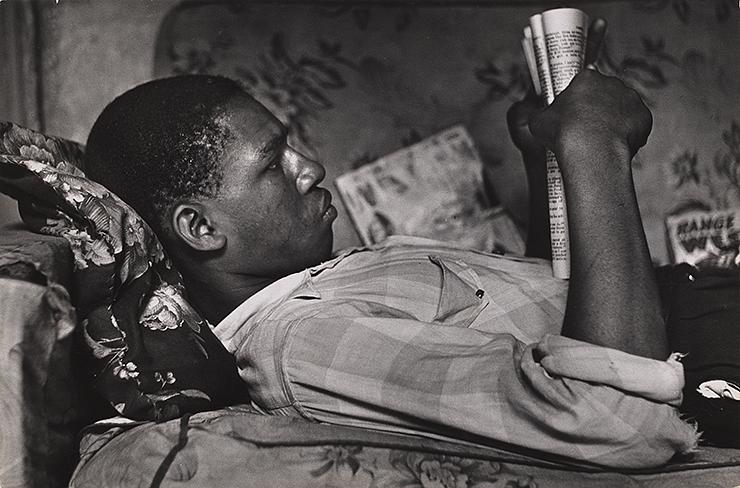

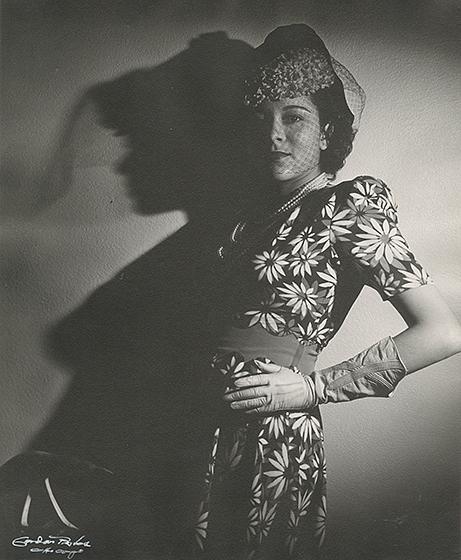

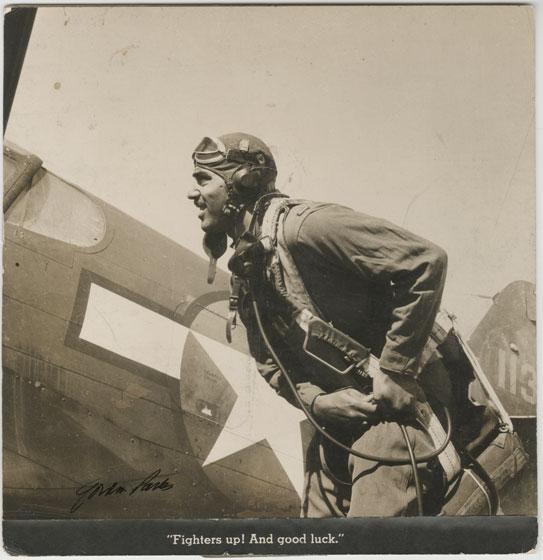

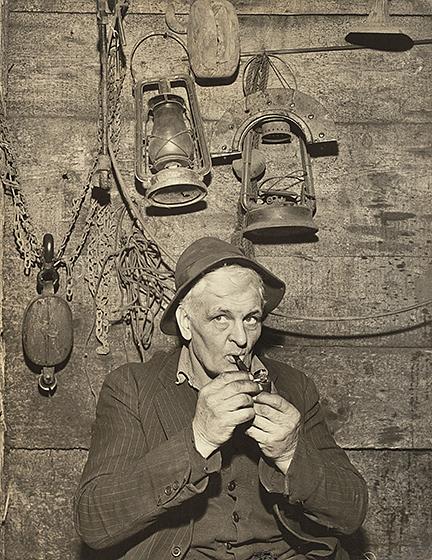

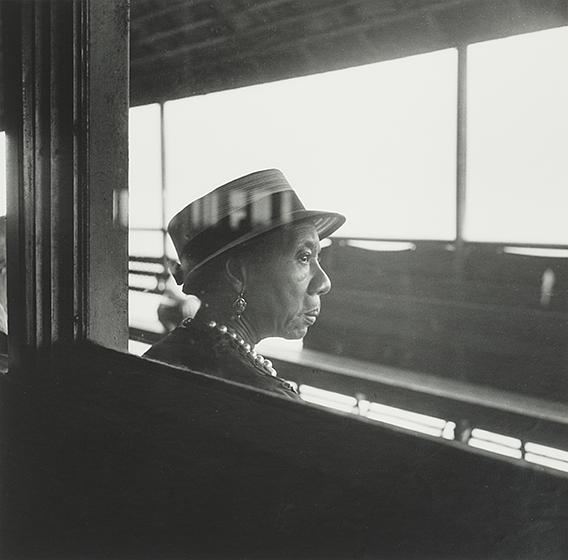

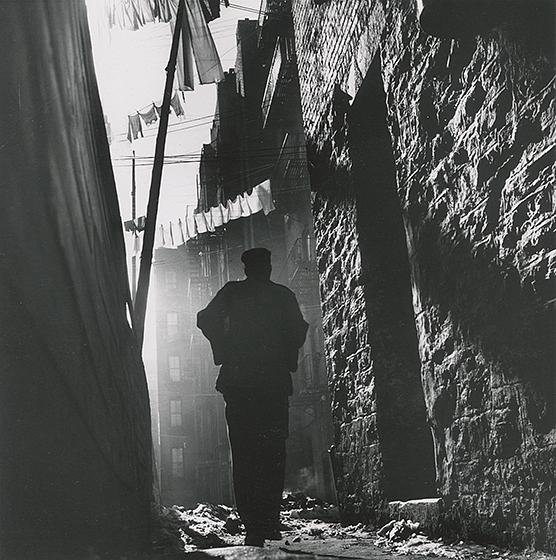

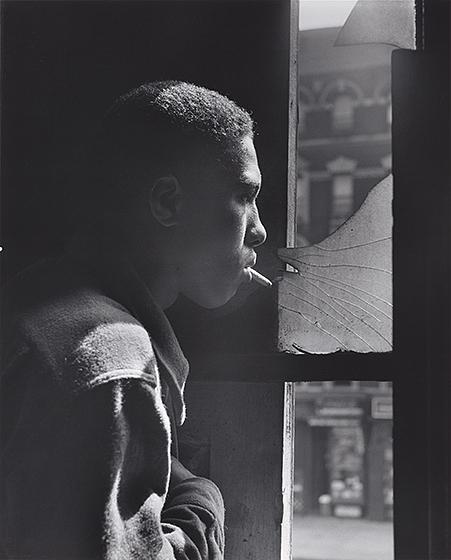

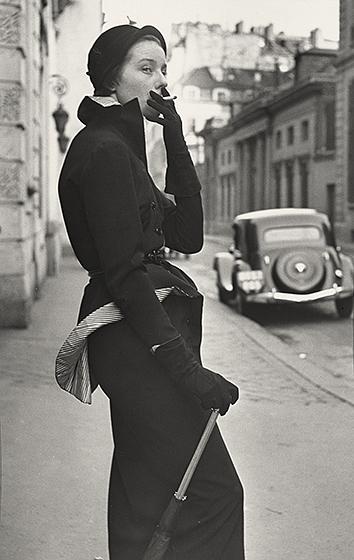

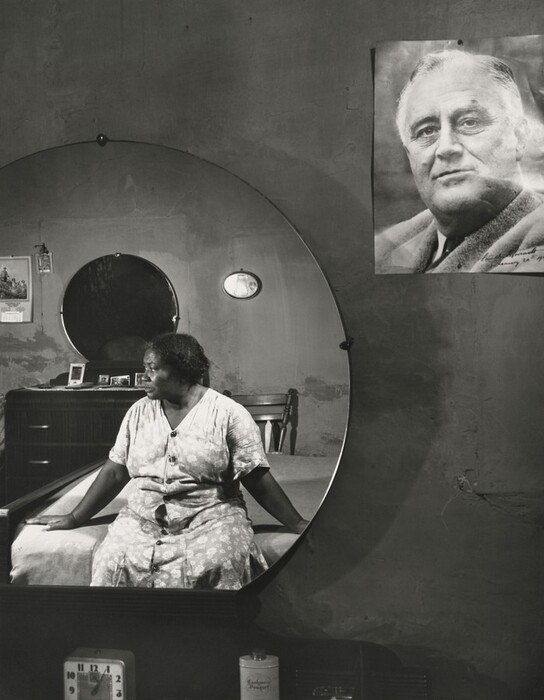

During the first decade of his career, Parks, a self-taught photographer, captured the beauty, power, and stature of Chicago socialite Marva Louis; the spirituality of churchgoers in Washington, DC; and portraits of prominent African Americans like Richard Wright and Marian Anderson. But he would also use his camera to shine a light on the injustices faced by black Americans, showing the poverty, violence, and oppression that defined the decade from 1940 to 1950. In the midst of World War II, with the American military still segregated, photographs like Washington, D.C., Government charwoman (American Gothic) make a bold statement about the disparities between the promise and realities of the American Dream. When given the chance, Parks chose to “fight back” against the inequalities he witnessed; his choice of weapons was a camera.

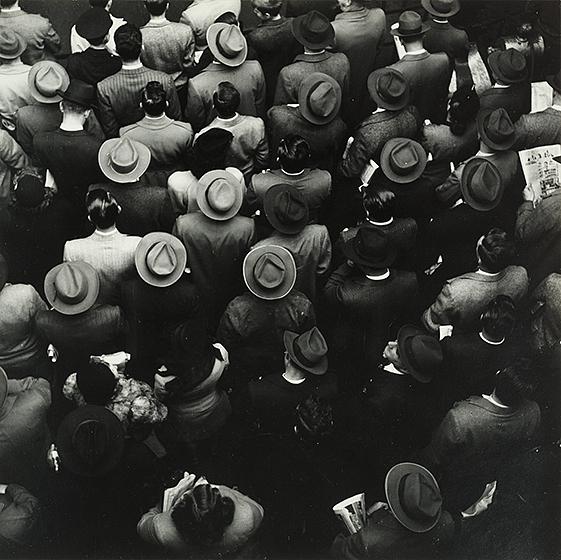

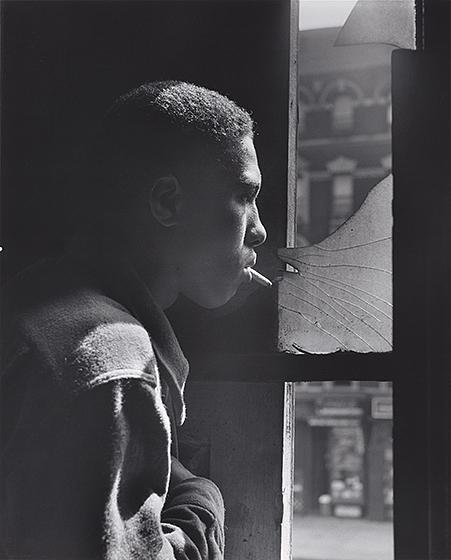

The photographs in this image set speak to the power of Parks’s voice as an artist. His images certainly serve as documents of specific moments in time; but individually and as a group they also reveal humanity, implore empathy, pose questions, provoke outrage, and even inspire activism. Though taken decades ago, Parks’s photographs capture individuals and represent issues and themes that still resonate deeply with us today.

Selected Works

Activity: Words and Images

In 1942, Gordon Parks arrived in Washington, DC, with a fellowship to work as a photographer at the Farm Security Administration (FSA). The Historical Section of the FSA was headed by Roy Stryker, who famously hired photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Jack Delano to document the impact of the Great Depression on American farmers. Stryker encouraged Parks to incorporate words into his photographic process, suggesting, “you can’t just take a picture of a white salesman, waiter, or ticket seller and just say they are prejudiced…[you] need to verbalize first and experience first, then find logical ways to express it in pictures.”

Still an apprentice at the FSA, Parks was directed by Stryker to first explore Washington, then a racially segregated city, without his camera in hand. He went to buy lunch and a new coat, and tried to attend a film, but as a black man, he was turned away each time.

Think about your own experiences in your school, community, or city. What needs changing? Write an essay on this subject and using a camera, capture images that visualize the injustices you wish to call attention to.

Activity: What Tells a Story

“I think Roy stirred the interest in me to try and get to know people and get to know all kinds of people better and investigate their ills and their prejudices and their goods and their evil.” —Gordon Parks, oral history interview, December 30, 1964, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

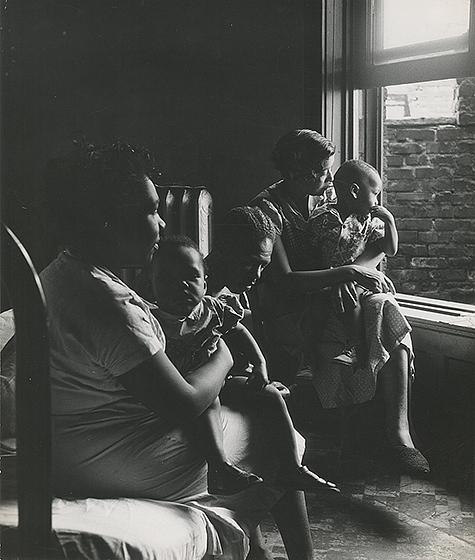

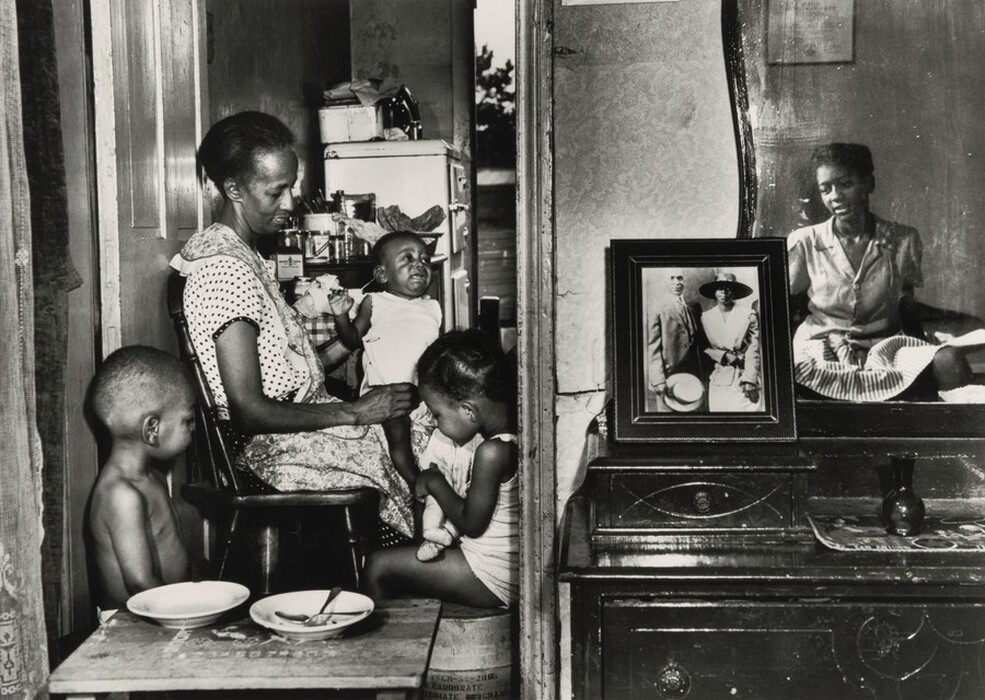

Early in his career at the Farm Security Administration, Gordon Parks was encouraged to consider how a series of photographs can tell a more complete story.

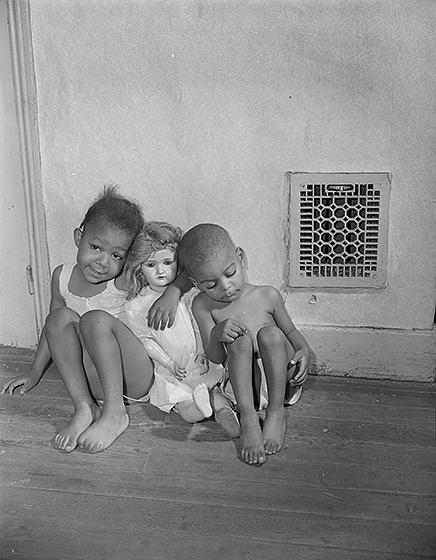

Using images of government worker Ella Watson and her family, split the class into groups and give each group one photograph from the series. Have each group discuss what story their particular image tells. Consider all of the elements of the photograph: subject matter, details, lighting, composition, perspective, and point of view.

Next, bring the class together to share the photographs and stories discussed. How does seeing all of the photographs together reinforce or change the story each group developed? Discuss what new stories you can now tell and what other connections you can make.

Try this exercise with other series in the image set. For instance, compare/contrast images detailing work of some kind. What do they say about labor in the United States? What can we learn about the nature of the American Dream?

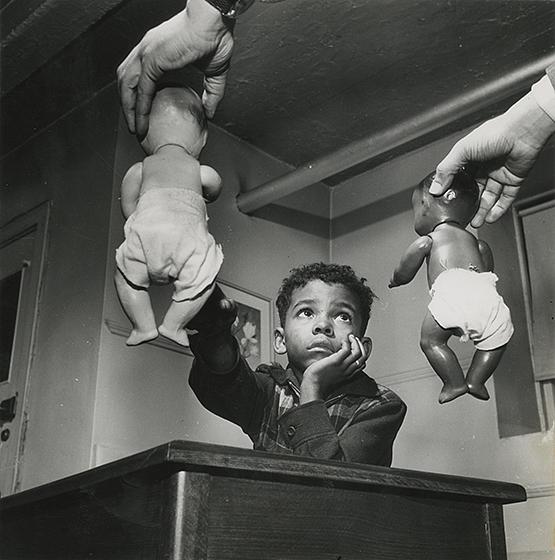

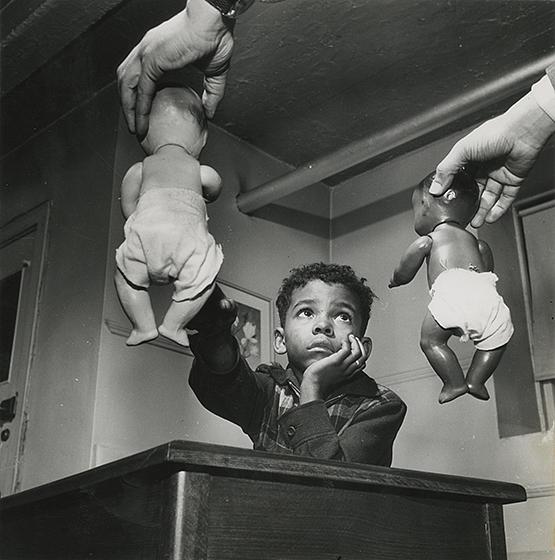

Or, compare/contrast Parks’s photographs of children. Why might Parks have focused on children in his work? What do photographs of children accomplish that his other images do not?

Activity: Making the Invisible Visible

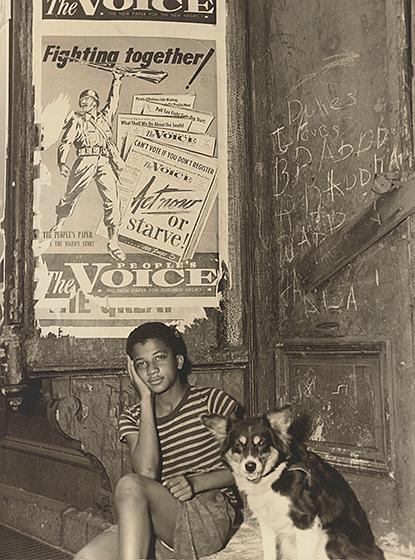

Gordon Parks and writer Ralph Ellison were friends and collaborators, simultaneously exploring through different means the daily injustices faced by black Americans. In 1948, Parks and Ellison walked the streets of Harlem together, photographing and writing about the connections between segregation and psychological health. Some of their findings were incorporated into Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, which explores themes of identity, community, stereotype, memory, and power through the voice of the narrator and his life experiences.

Ask students to identify and select five key passages from Invisible Man that focus on the broad themes identified above. Ask them to select one or two images from the set of pictures that Parks made in Harlem that focus on the same themes. How did Ellison and Parks explore each theme differently? What did each choose to focus on? Ask the students to explain which creative work they find more powerful, the text or the image, and why.

Additional Resources

Ella Watson United States Government Charwoman, Documenting America, Library of Congress

You may also like

Educational Resource: Uncovering America: Activism and Protest

Artists in the United States are protected under the First Amendment, which guarantees freedoms of speech and press. This module features works created by artists with a range of perspectives and motivations.

Educational Resource: People and the Environment

The US national park system exists in part because of artists.

Educational Resource: Faces of America: Portraits

The basic fascination with capturing and studying images of ourselves and of others—for what they say about us, as individuals and as a people—is what makes portraiture so compelling.