Maria Berbara

Extracting Resources, Extracting Life: Brazilwood and Extreme Longevity in Early Modern European Colonial Prints and Maps

My time at the Center was principally devoted to completing a chapter of my book, which looks at the cultural representation of health, longevity, and disease in the early modern Americas, with a geographic emphasis on what today roughly corresponds to Brazil.

The trope of Native Americans living over 120, 150, and sometimes 200 years—which is very common in early modern European sources—is at the center of my project’s narrative. It acts as a thematic thread to understand early modern dichotomies related not just to life and death, but also to paradise and hell, good and evil, health and disease, youth and senility, and even past (for example, the Golden Age or Eden) and present. To this end, my project juxtaposes political and cultural history, confronting reality as it was fabricated and perceived in images with archival material and contemporaneous scientific data regarding the ecological impact of European colonization of the Americas.

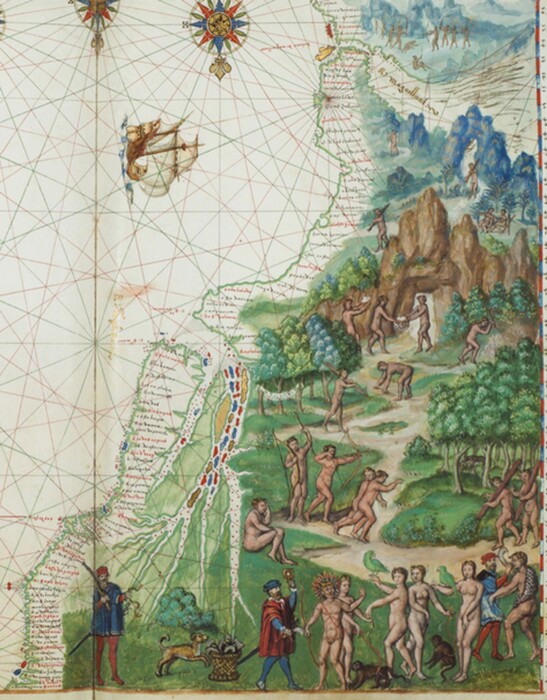

Detail of portolan atlas (so-called Vallard Atlas) representing the coast of South America, 1547, The Huntington Library

The massive arrival of Europeans, Asians, and enslaved Africans to the American continent in the early modern period ushered in a demographic collapse that caused millions of human deaths. In spite of this scenario, in the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans often imagined, described, and pictured the original inhabitants of the Americas as youthful, healthy, and extremely long-lived. In my book chapter, I propose a way to explain these constructs.

I studied hundreds of book illustrations and maps showing how early modern Europeans imagined Native Americans as the workforce for extracting brazilwood. These included prints from editions of works by Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512), Hans Staden (c. 1525–c. 1579), André Thevet (1516[?]–1592), and Jean de Léry (1534–c. 1611), as well as printed and manuscript maps produced mainly in Normandy. Many of those images—as well as their accompanying texts—represent the laborers as athletic, strong, and forever-young Natives effortlessly filling French commercial vessels with goods collected from paradisiacal forests and fields.

I have investigated how certain visual codes pertaining to different genres—from biblical iconography to the classical tradition, and from utopianism to depictions of travel accounts in the New World—intermingled and cross-pollinated in the representation of group interactions, poses, and physical attributes of Indigenous workers. A French print produced in 1551, which represents the so-called “Brazilian Feast,” for example, includes a group of Native Americans dancing around a tree, a vignette that is repeated in Pierre Devaux’s 1613 world map, also in connection to Brazil. This configuration is not at all unusual in European representations of the time, including a well-known painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder produced around 1530. There, as well as in the 1551 French print, the dance scene is connected with eroticism, youth, and the fertility of the land.

From left to right: Detail of engraving from C’est la déduction du sumptueux ordre plaisantz spectacles et magnifiques theatres dressés… (Rouen: Robert le Hoy, 1551), Bibliothèque nationale de France; Pierre Devaux, Detail of “Portefeuille 116 du Service hydrographique de la marine consacré à l’océan Atlantique,” 1613, Bibliothèque nationale de France; Lucas Cranach the Elder, Golden Age (detail), c. 1530, oil on panel, Alte Pinakothek

In addition to religious and existential considerations about the Native Americans’ soul and intellect, they were an essential part of colonial economic and mercantile machinery. Predatory extraction of goods—especially wood, in the case of Brazil, but also minerals and exotic animals—was the primary motivation for financing expeditions and settlements in the region. It became essential to represent Natives as collaborative, strong, young, docile, and capable.

Extractivist practices inaugurated by European colonial powers in early modern America were paired with visual and literary formulas that connected the New World to ideas of abundance, overflow, eternal spring, and youth. Just as Native peoples were perceived as never sick and capable of living for many years, so too plants, animals, and minerals were considered inexhaustible—or, at least, easily replaceable.

My Center fellowship allowed me not only to consult bibliographical and iconographical materials that I could not have accessed from home, but also to have the time and structure to conceptualize my project. In addition to the excellent resources of the National Gallery’s library and art collections, it was possible to visit other museums and libraries in Washington, such as the Library of Congress.

Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro

Beinecke Visiting Senior Fellow, November–December 2024

Maria Berbara will return to her position as full professor of art history at the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, where she will continue to work on her book and the Getty-funded project “The Amazon Basin as Connecting Borderland: Examining Cultural and Artistic Fluidities in the Early Modern Period.”

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.