Roland Betancourt

Art and Automation

Visitors watch parts fly by on an overhead conveyor at the Ford River Rouge, from “Tour Through the Rouge Plant,” c. 1939, National Archives at College Park, NAID 93713

During my first year at the Center, I have dedicated my attention to completing two book-length monographs on the role of automation, the corporation, and the theme park in the postwar period, building on my earlier research in the history of science and technology, the senses, and performance in the premodern world.

The first book, Disneyland and the Rise of Automation (2026), looks at how the modern amusement park was built around the technologies and dialogues surrounding automation in the postwar period. This book traces the technological evolution of Disneyland’s attractions over its first three decades to show how automation technologies were adapted and aestheticized amid concerns about machines replacing humans in society. This book asks pressing questions about how our relationships with technology are mediated by our visual culture and how the rise in autonomous, thinking machines was aestheticized throughout the postwar period.

The second book, The Corporate Imaginary: The Postwar Corporation and the Invention of the Theme Park, focuses on the transformations of the corporation through the organizational concepts that were peddled by mid-century business consultants and think tanks, such as decentralization and diversification. In one chapter, for instance, I trace how the Stanford Research Institute deployed the policies and practices developed for the dispersion of industry under the threat of nuclear attack to select a site for the Disneyland theme park. Through in-depth examination of extensive corporate archives and declassified documents, this book asks why the theme park became such a ubiquitous mode of expression for the corporation, demonstrating in the process how the theme park was a direct by-product of postwar managerial concepts.

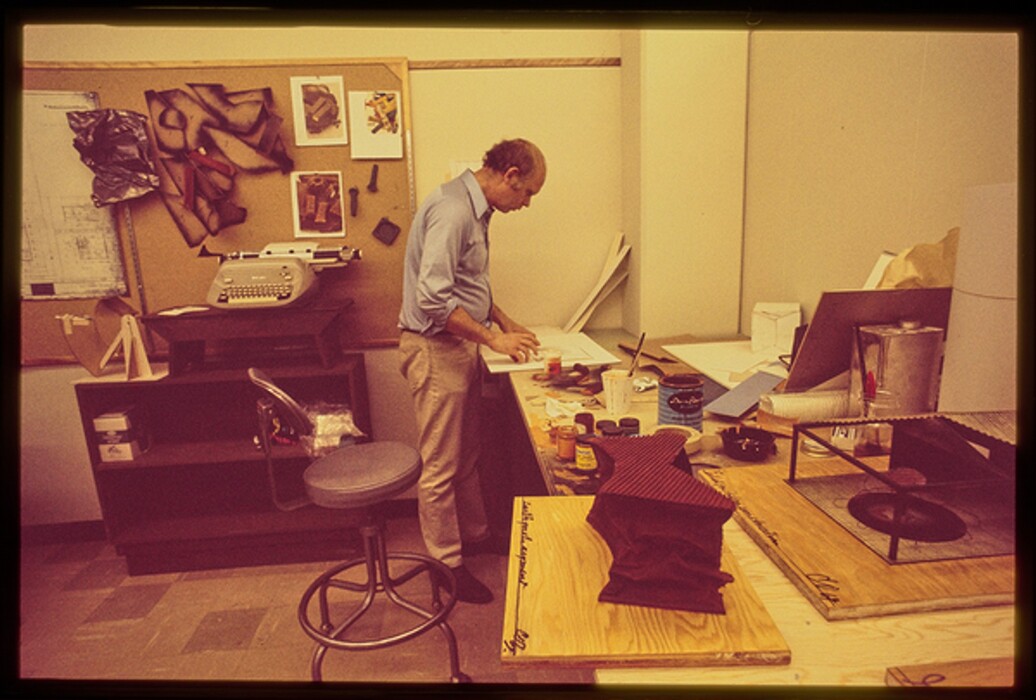

Claes Oldenburg working in his office at Walt Disney’s WED Enterprises, May 1969, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Modern Art Department Art and Technology records

In April 2025, I organized a one-day workshop at the Center entitled “Gold & Flatness: Byzantine Art after the Middle Ages.” Much scholarship today has highlighted the critique that “Byzantium” is an anachronistic term to describe the medieval Roman Empire, once centered on Constantinople. An invention of the early modern period, Byzantium is instead an artifact of European machinations: on the one hand, seeking to disentangle the empire from European history “proper” and, on the other hand, desiring to weaponize Byzantine history as a foil against eastern enemies, particularly the Ottoman Empire. Concepts like flatness, frontality, gold, revetments, inverse perspective, and so on developed not so much out of Byzantine art itself, but from a host of diverse, global artists responding to and refracting Byzantine art through their own religious, imperial, colonial, and subversive projects. The seminar brought together a wide range of scholars to examine the meandering lives of Byzantine art from the invention of Byzantium into the present, seeking for the first time to critically examine the promiscuous permutations of a style through its centuries of confusion, elision, and reinvention.

In between these projects, I have also completed two articles on topics deriving from my theme park project. One, “Pushbutton Aesthetics,” looks at the embodied practices and skills of factory operators, whose labor has often been de-skilled in the popular imagination. This article proposes that conventional art-historical methods can be used to articulate and contextualize the skill of these operators in a way that stresses the dialogic intimacies between control consoles, gestures, and the senses. A second article, reaching across Byzantium and into the present, looks at the notion of things “made without human hands” (acheiropoeita), an idea developed in Byzantium to explore the ways in which the divine manifested itself, both in miracles and in miraculous icons. In the 1950s, concomitant with burgeoning discourses around the coining of the term “automation,” we find this idea of things “untouched by human hands” to describe automation’s products. This article questions the entanglements between the ideas of the miraculous and the automated with critical reflections on ideas of humanity and slavery that were at the heart of these discussions, both ancient and modern.

University of California, Irvine

Andrew W. Mellon Professor, 2024–2026

Roland Betancourt will begin his second year as the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the fall.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.