Sarah Cash

John Singer Sargent’s Stereographs Rediscovered

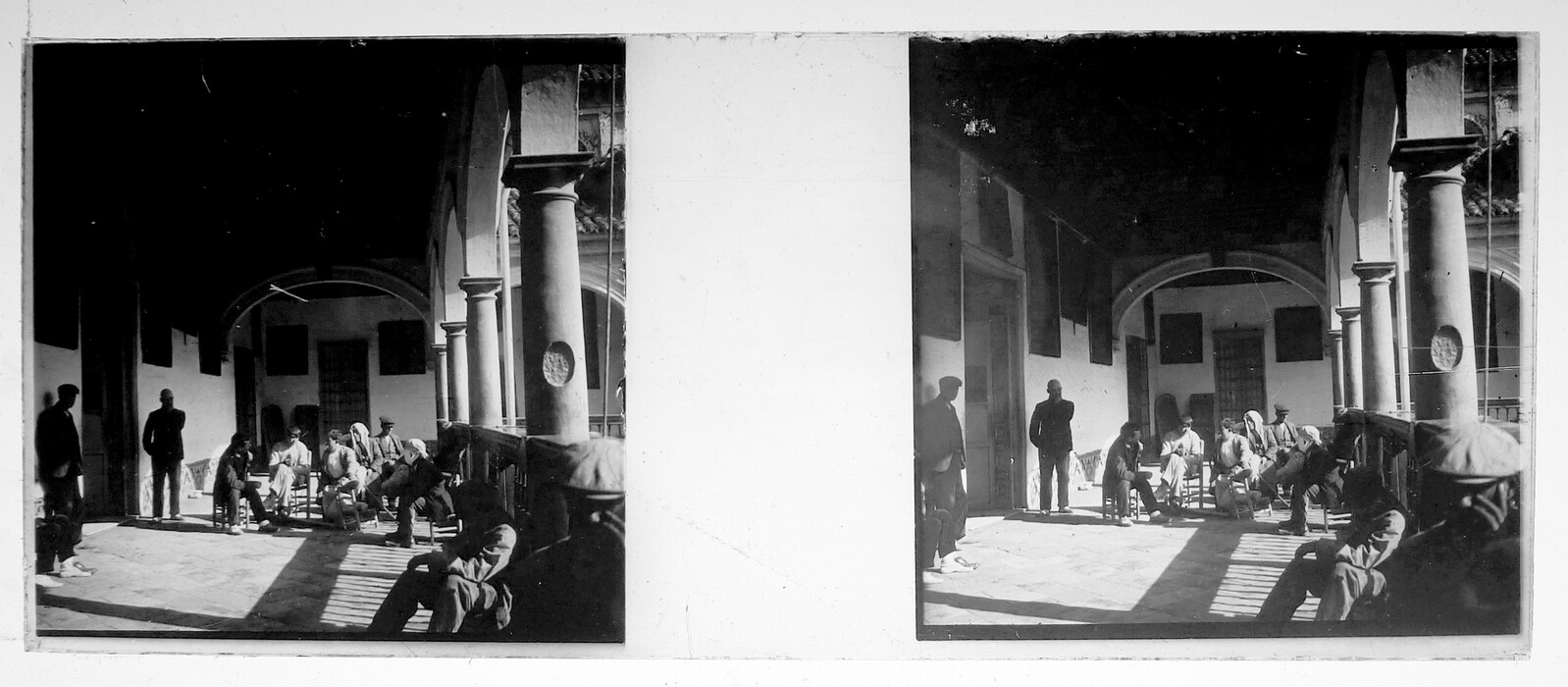

John Singer Sargent, Hospital at Granada, 1912, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1924. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

In 1907 John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) declared a change of course from his demanding work as a painter of commissioned “paughtraits,” as he called them. “I abhor and abjure them and hope never to do another especially of the Upper Classes,” he wrote to his friend Ralph Wormeley Curtis. The primary subject of my fellowship research, a virtually unknown cache of 194 glass stereographs taken by the artist from 1908 to 1913, sheds new light on this transitional phase of Sargent’s career. As he increasingly turned to landscapes, genre scenes, portrayals of friends and family, and the medium of watercolor, Sargent also embraced the new by creating photographic aide-mémoire during his travels. He traveled not only with his stereograph camera but also with a Kodak postcard camera, creating photographic postcards that, like the stereographs, often served as studies for finished oils and watercolors.

This research grew out of my Sargent and Spain exhibition (2022–2023), when I received digital images of the stereographs. Following Sargent’s death in 1925, these small glass plates (preserved in their original, labeled boxes), his Jules Richard Vérascope stereograph camera, Mattey Standard Stereoscope viewer, and one other handheld viewer transferred to his frequent travel and painting companion Wilfrid de Glehn (1870–1951). The 194 Sargent stereographs descended in de Glehn’s family in England, where they were supplemented over the years by photographs taken with the Vérascope camera (and others) to total approximately 1,500 plates. I visited the collection’s present owner in Cornwall in July 2024 to examine the stereographs and equipment. I also visited a de Glehn family member in Cambridge, who has been engaged in family research. Previously, I spent time in London with Sargent experts Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray to benefit from their observations about the people and locales depicted in the stereographs. I have also studied a collection of small gelatin silver prints—related to Sargent and his travels but by unidentified photographers—in the John Singer Sargent Archive at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

John Singer Sargent, Hospital at Granada, 1912, glass stereograph, private collection. Photo: Valerie Langfield

Early in my sabbatical fellowship, it was important to confirm my hypothesis that most of the 1,500 stereographs postdate Sargent’s lifetime and instead document de Glehn family, friends, and travels. This required a thorough examination of the people, locales, and clothing styles depicted in the photographs. Subsequently, aided by Ormond’s and Kilmurray’s observations, their nine-volume John Singer Sargent: The Complete Paintings, consultations with many National Gallery and external colleagues, and a trip to Granada in Spain, I have been able to identify nearly all of the locales, events, people, and details depicted in the 194 stereographs that do relate to Sargent. My study of the photographs’ connections to Sargent’s extensive travels and their compositional similarities to many of his completed oils and watercolors makes clear that they were taken by Sargent. This is underscored by the recent identification of the specific type of tabletop stereograph viewer (now lost) that appears in photographs of the artist’s Tite Street studio. It is a Jules Richard Taxiphote viewer, used specifically for glass stereographs. I have compiled all of this research into an Airtable database.

I have also completed significant reading on the topic of painters and photography and have consulted with several Sargent scholars in addition to Ormond and Kilmurray, as well as experts on other artists who utilized photography in their work, such as Winslow Homer (1836–1910) and Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). To date I have been able to take approximately half of my four-month fellowship; I hope to spend most of July and August 2025 on the project. In the remaining time, I plan to expand and refine my Airtable database; obtain and study higher-resolution digital photographs of the stereographs; visit Rochester, New York, to consult with the foremost specialist on stereographs; view additional photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, that relate to Sargent’s possible camera use; work with the plans and elevations of Sargent’s Tite Street home and studio to further study the stereographs that document the interior of his home and the art he displayed there; and more. I hope to give a lunchtime talk at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and potentially outline an article for Panorama, the peer-reviewed journal of the Association of Historians of American Art.

Department of American and British Paintings

Ailsa Mellon Bruce National Gallery of Art Sabbatical Fellow, 2024–2025

Sarah Cash will return to her duties as associate curator in the Department of American and British Paintings at the National Gallery of Art. She hopes to publish some of her research in Panorama and ultimately publish all of it in a book that may accompany a small National Gallery exhibition.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.