About Alfred Stieglitz: Career Overview

Publication History

Published online

On this Page:

Early Europe, 1886–1894

Alfred Stieglitz, The Last Joke—Bellagio or A Good Joke, 1887, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.30

Key Set number 33

Alfred Stieglitz, The Last Joke—Bellagio or A Good Joke, 1887, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.30

Key Set number 33

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1864, Alfred Stieglitz began studying photography while a mechanical engineering student in Berlin. His teacher, Professor Hermann Wilhelm Vogel (Key Set number 1), an expert in photographic science and practice, encouraged Stieglitz to investigate the medium’s properties and possibilities by tackling a range of subjects, including landscape, portraiture, architecture, genre studies, and the reproduction of artworks (Key Set number 30).

Deeply influenced by German popular painting of the time—which often focused on picturesque rural scenes of daily life—Stieglitz traveled around Europe from 1886 to 1890 in search of similar subject matter to photograph. Some of his scenes are melodramatic (Key Set number 42) or sentimental (Key Set number 62), but others capture more spontaneous moments (Key Set number 33).

Alfred Stieglitz, A Street in Sterzing, The Tyrol, 1890, platinum print with mercury, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.64

Key Set number 72

Alfred Stieglitz, The Net Mender, 1894, carbon print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.199

Key Set number 212

Alfred Stieglitz, The Net Mender, 1894, carbon print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.199

Key Set number 212

Despite the success these photographs brought him, Stieglitz later destroyed most of his early European works—likely because their old-fashioned, “painterly” sensibility deviated from the modernist path he later traced for himself. More than three-quarters of the vintage prints in the Key Set made before 1896 likely escaped this fate because they are contained in four bound albums, each titled Sun Prints (1895–1896), which he gave to family members. The Key Set also includes two smaller albums from this early period: Freienwalde a. O. (1886), which chronicles a humorous outing with fellow students, and A Souvenir of Summer (1886), which records a family vacation in Mittenwald, Germany.

Early New York, 1890–1904

Alfred Stieglitz, Winter, Fifth Avenue, 1893, printed 1894, carbon print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.93

Key Set number 82

When Alfred Stieglitz returned to the United States from Germany in 1890, he made New York City his central subject. He walked the streets with a handheld camera, which allowed for more spontaneity than a large camera mounted on a tripod. He concentrated, as he had in Europe, mainly on working-class scenes of daily life, albeit now conveyed with a greater immediacy (Key Set number 77).

Stieglitz soon realized that technical challenges other photographers largely shied away from, such as rain, snow, and low light, could be a boon to his picture-making. Although such conditions were difficult to work in, they helped unify compositions, softened the unruly city, and tied it to nature. In 1893 he made his first “snow picture” of a stagecoach driving down Fifth Avenue in a blizzard (Key Set number 82). The next day, he came upon a streetcar driver washing down his horses; the steam rising from their overheated backs resembles mist over a lake (Key Set number 92). In his quiet night pictures of 1897–1898, the city, invariably robed in rain or snow, feels nearly empty, with the compositions dominated by trees and the halation of distant lights (Key Set number 257).

Alfred Stieglitz, The Hand of Man, 1902, printed 1910, photogravure on beige thin slightly textured laid Japanese paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.269

Key Set number 278

Alfred Stieglitz, The Hand of Man, 1902, printed 1910, photogravure on beige thin slightly textured laid Japanese paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.269

Key Set number 278

Alfred Stieglitz, The Flatiron, 1903, printed in or before 1910, photogravure on beige thin slightly textured laid Japanese paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.272

Key Set number 288

Alfred Stieglitz, The Flatiron, 1903, printed in or before 1910, photogravure on beige thin slightly textured laid Japanese paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.272

Key Set number 288

After the turn of the century, Stieglitz brought a similar pictorial sensibility to hallmarks of New York’s modernity. His 1902 photograph of a steaming locomotive in a Queens train yard transforms a soot-filled scene of industrial power into one of atmospheric beauty (Key Set number 278); its symbolic title, The Hand of Man, alludes to both the modern reshaping of the landscape and the mechanical process of photography itself. The next year Stieglitz trained his lens on New York’s audacious new skyscraper, the Flatiron Building, but he muted its uncompromising modernity by framing it with snow-dappled trees (Key Set number 288).

Unlike his early European photographs, which he later mostly disavowed, Stieglitz embraced his early New York photographs as marking the start of his modernist trajectory.

The 291 Years, 1905–1917

From 1905 to 1917, Alfred Stieglitz made relatively few photographs. He was busy overseeing a new journal, Camera Work (1903–1917), and consumed first with promoting the art of his handpicked group of photographers, the Photo-Secession, and later with modern European art; he exhibited both at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession on Fifth Avenue, known (after its street number) as 291 (1905–1917). Though few, Stieglitz’s works from this period mark a significant turn from pictorialism, with its emphasis on atmosphere, to a more modernist-influenced concern for the underlying geometric structure of a composition.

In 1907 Stieglitz made what he later considered his first modernist photograph: a view of ship passengers in steerage, taken from the first-class deck (Key Set number 313). With its dense, grid-like patterning and compressed pictorial space, the photograph has an almost cubist structure—a connection Stieglitz first highlighted in 1911, when he published it in an issue of Camera Work that also included a cubist drawing by Pablo Picasso.

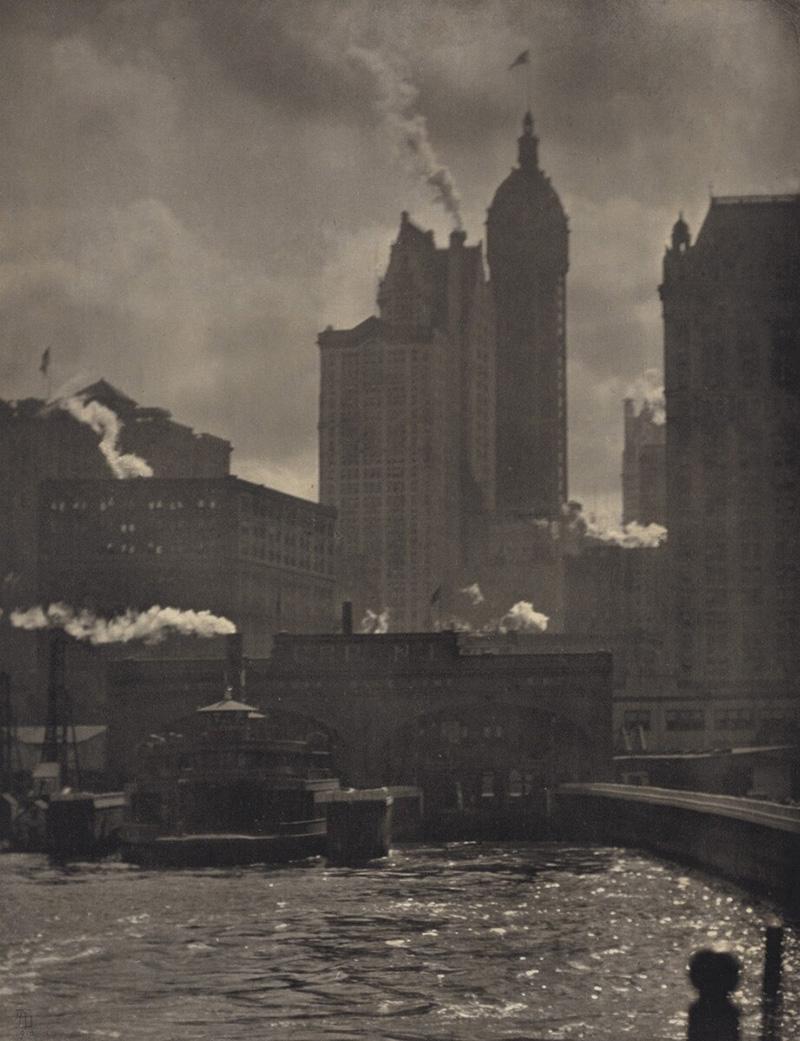

Stieglitz in 1910 made a series of photographs focusing on the modernity of New York City. The monumental The City of Ambitions—a view of the Manhattan skyline from a ferry—features the soaring Singer Building and plumes of smoke that attest to the city’s bustling activity (Key Set number 342). In his rigorously composed view of the sleek Mauretania, the world’s largest and fastest ocean liner, the shapes on the pier in the foreground are echoed in the ship’s funnels, uniting the city with the triumphs of modern technology (Key Set number 334). Old and New New York, in which the geometric frame of a massive building under construction looms over low-slung brownstones, points to the city’s—and Stieglitz’s—modernist future (Key Set number 344).

Alfred Stieglitz, Francis Picabia, 1915, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.363

Key Set number 403

After 1910, Stieglitz turned his photographic attention to making portraits of his circle of artists and colleagues. He made his gallery, 291, his informal portrait studio, reinforcing its primacy as the epicenter of modern art. The soft focus and brooding lighting of his first portraits (Key Set number 369) gave way to a more direct style by 1913, when he started posing sitters in front of works of art—often, if they were artists, their own (Key Set number 384). In these complex, multilayered portraits, Stieglitz expressed his understanding of a subject’s personality by linking sitter, setting, and formal elements; a portrait of Francis Picabia, for instance, rhymes an archlike shape in the painting with the painter’s brow and hunched shoulders, and the back of the chair on which he sits (Key Set number 403).

In 1915 and 1916, Stieglitz made a series of photographs out of 291’s back window that marked a turning point in his understanding of modernist photography (Key Set number 417). Unlike his earlier vistas of the city’s iconic sites and structures, these humble views lacked any obvious drama. But Stieglitz explored this cityscape not for its subject matter, but to study form—much as Picasso had done with his cubist studies of the Spanish village of Horta. With their compressed space, simplified geometric forms, and stacked and tilted planes, these photographs embody Stieglitz’s conscious translation of cubism to photography.

Alfred Stieglitz, From the Back-Window—291, 1915, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.372

Key Set number 417

Alfred Stieglitz, From the Back-Window—291, 1915, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.372

Key Set number 417

Georgia O'Keeffe, 1918–1920

In 1917, amid the tumult of US entry into World War I, the two great projects that had consumed Alfred Stieglitz for more than a decade—Camera Work and the gallery 291—came to an end. The next year, the fifty-four-year-old photographer and the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, who was twenty-three years younger, became lovers, catalyzing a burst of creativity unprecedented in Stieglitz’s long career: from 1918 to 1920, Stieglitz made more than 140 photographs of O’Keeffe that, unlike his earlier analytic work, resonated with emotion and personal meaning.

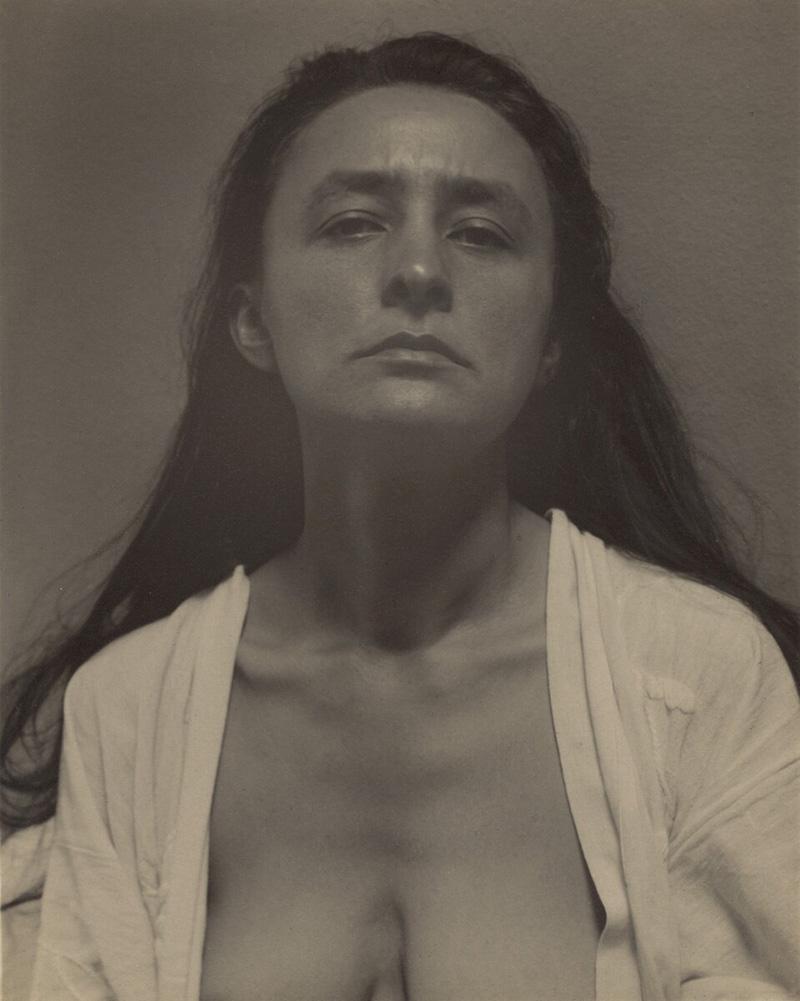

Stieglitz made his first portraits of O’Keeffe at 291 in 1917, shortly before the gallery closed. Like his other 291 portraits of artists, Stieglitz posed O’Keeffe in front of her art; in one her head is framed, halolike, by a circular form in her drawing (Key Set number 457). He continued to pose O’Keeffe in front of her drawings in 1918, but as their intimacy grew, he began to conjoin her art and her body, suggesting they were one (Key Set number 490).

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918, printed 1924/1937, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1980.70.66

Key Set number 490

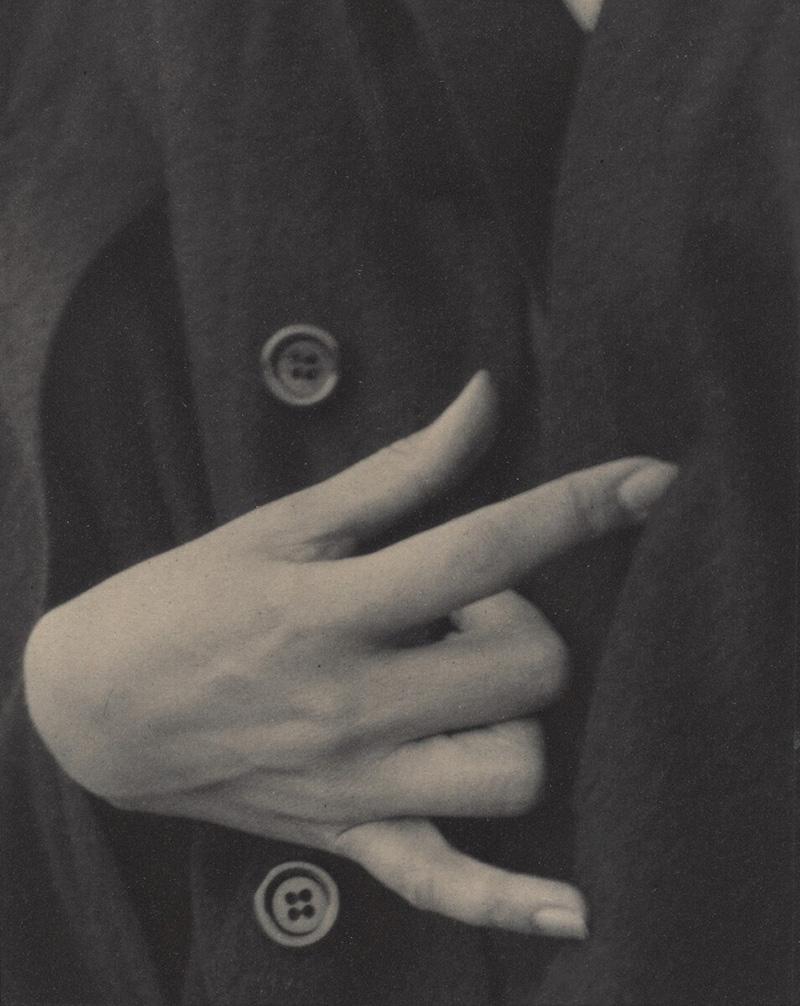

As O’Keeffe quickly became more comfortable with his scrutiny, Stieglitz focused on her less as an artist than as a lover. In several photographs, wearing a loose or open kimono, she looks directly and longingly at the camera (Key Set number 501). Other photographs lavish attention on isolated parts of her body, including her torso, legs, feet, and hands. These independent studies express Stieglitz’s passion as well as his belief that different body parts were expressive of O’Keeffe’s individuality (Key Set number 514). The many portraits of her hands, in particular, including extreme close-ups, evoke an intimate sense of touch (Key Set number 531).

Stieglitz conceived of his portraits of O’Keeffe as a single work—a composite portrait. Each photograph stands on its own, revealing a certain innate quality at a given moment. But because change is a constant, only a series of photographs can evoke a subject’s entire being over time. To underscore the composite nature of his project, in 1921 Stieglitz exhibited more than forty photographs of O’Keeffe—many clustered by body part—under the title “Demonstration of Portraiture.”

Stieglitz and O’Keeffe married in 1924, and he continued to photograph her through the 1930s—his composite portrait eventually numbering 331 works. But his pictures of her changed markedly over the years. In 1923 when he became entranced with photographing clouds, he made smaller, more casual pictures of her at work or holding the subjects of her paintings. Many of his portraits of her from the 1930s lack the feverish intensity of those he made from 1918 to 1920 and reveal instead the distance in their relationship.

The 1920s

In the 1920s, Alfred Stieglitz made Lake George, where he spent summers at his family’s home, the locus of his photographic explorations. He stayed in close touch with the 291 crowd, many of whom he exhibited at his new space in New York, the Intimate Gallery (1925–1929). But he also embraced his new role as a father figure to a circle of young writers and critics, including Sherwood Anderson (Key Set number 846) and Paul Rosenfeld (Key Set number 644), who advocated an American form of modern art tied not to theory, but to intuition and direct observation—especially of the countryside. Amid this new intellectual milieu, Stieglitz looked extensively at Lake George’s rural landscape for his subjects, making photographs of hills, trees, and barns (Key Set number 862).

In a conscious effort to grant his intuition freer rein, Stieglitz sought to photograph subjects over which he had little control. Forsaking slow and deliberate composition for quick reaction, he started making snapshots, including a joyous, almost cinematic series of eighteen photographs of Rebecca Strand swimming nude and toweling dry (Key Set number 751).

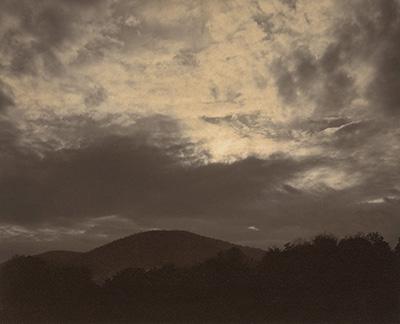

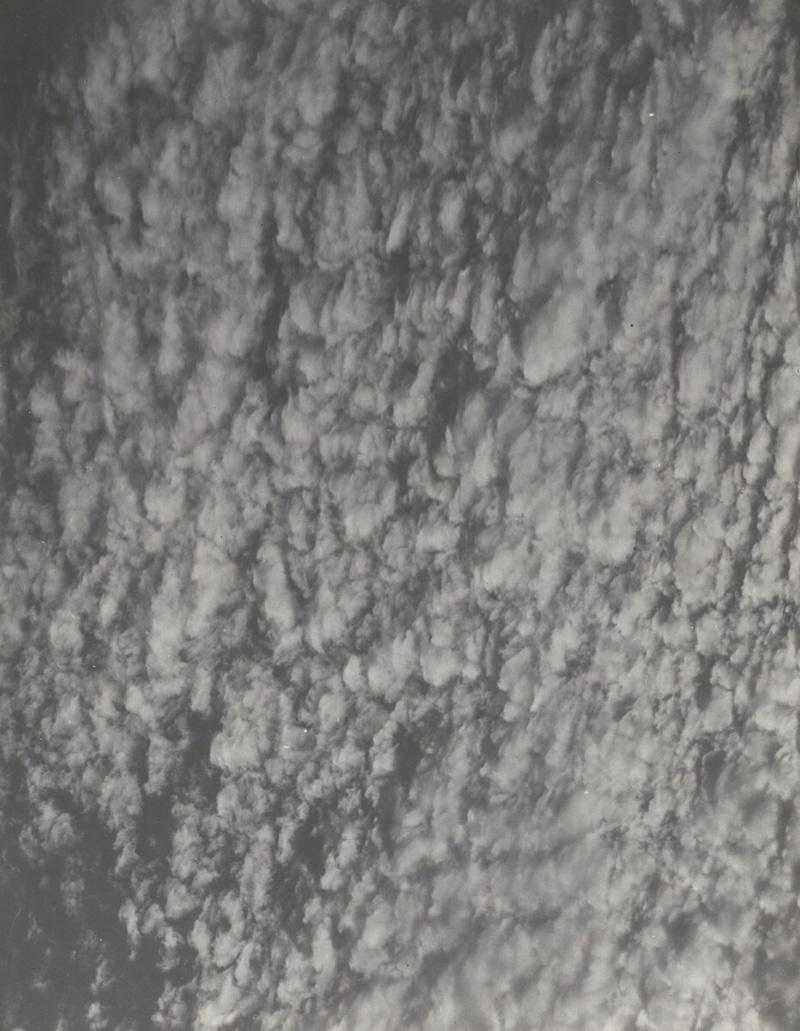

Stieglitz’s interest in seriality, intuition, and expression culminated in his unprecedented series of cloud photographs, which preoccupied him for most of the decade. His first series of ten photographs, made in 1922 with a large, 8 × 10-inch view camera, depicts clouds over the hills of Lake George (Key Set number 795). In the summer of 1923, Stieglitz became obsessed with photographing clouds, making more than 150 pictures. But now using a handheld camera that he could point anywhere in the sky, he was able to eliminate any reference to the ground (Key Set number 944). The resulting photographs are disorienting: with no anchor for the viewer and no sense of scale, they are simultaneously representational and abstract.

Stieglitz referenced music in the titles of his cloud photographs from 1922 (Music: A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs) and 1923 (Songs of the Sky), linking the abstraction inherent in music to the forms of the clouds. But starting in 1925, he began calling them Equivalents—a recognition that he saw the clouds as a vehicle to reveal his own thoughts and feelings (Key Set number 1114). As Stieglitz would later say, he saw the cloud photographs as “equivalents of my most profound life experience.”

For exhibitions, Stieglitz grouped the photographs into series. However, the series were not sequential or immutable, and the same photograph could appear in several series, sometimes oriented differently—always a reflection of Stieglitz’s subjective state.

The 1930s

Alfred Stieglitz, From My Window at An American Place, North, 1931, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.1231

Key Set number 1377

Alfred Stieglitz, From My Window at An American Place, North, 1931, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.1231

Key Set number 1377

In the early 1930s, Alfred Stieglitz again made New York City a subject of his work. His final gallery, An American Place, which he opened soon after the stock market crash of 1929, overlooked the city from the seventeenth floor of a new Madison Avenue office building. From those windows (Key Set number 1377), and from those of his thirtieth-floor apartment at the nearby Shelton Hotel (Key Set number 1391), Stieglitz recorded the frenzied building boom that transformed New York in the Great Depression.

Once settled on a particular view, Stieglitz made several variations at different times of day over the course of weeks or months, registering the growth of the buildings, the changing light and shadows, and the passage of time. Mostly shot head-on with his large, 8 × 10-inch view camera, Stieglitz’s rigorous compositions, rendered as crystalline gelatin silver prints, bespeak order and clarity. But for all of their formal beauty, they also represent the city as cold and inhuman—as Stieglitz made plain when he exhibited them in 1932 together with his earlier, more hopeful views of New York.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1933, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1980.70.317

Key Set number 1516

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1933, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1980.70.317

Key Set number 1516

The early 1930s marked a rocky period in the Stieglitz–O’Keeffe relationship. Georgia O’Keeffe became increasingly independent, spending summers in New Mexico starting in 1929. Stieglitz began an affair with a much younger woman, Dorothy Norman. Stieglitz depicts O’Keeffe with symbols of her independence, such as her southwestern blankets (Key Set number 1437) and animal bones (Key Set number 1432), or the new car she had just bought (Key Set number 1516). Strong formal studies, they speak to the chill between them. At the same time, as O’Keeffe knew, Stieglitz was eagerly making photographs of Dorothy Norman (Key Set number 1367).

Alfred Stieglitz, Poplars—Lake George, 1935, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.750

Key Set number 1575

Frequently alone at Lake George, Stieglitz, who turned seventy in 1934, started making quiet, autobiographical works based on his surroundings. A photograph of the small wooden building O’Keeffe used as her studio, with a dead tree branch extending across the doorway, evokes her absence (Key Set number 1557). Stieglitz also made photographs of nature in which he tried to bring the visual clarity that he imposed on New York City to the rural landscape (Key Set number 1508). Most poignantly, for much of the decade Stieglitz made a series of studies recording dying poplar trees, which he saw as emblems of himself (Key Set number 1575).

Ill health forced Stieglitz to put down his camera for good in 1937. He died in 1946.