Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: The Mourning Saint John the Evangelist, c. 1270/1275

Publication History

Published online

Entry

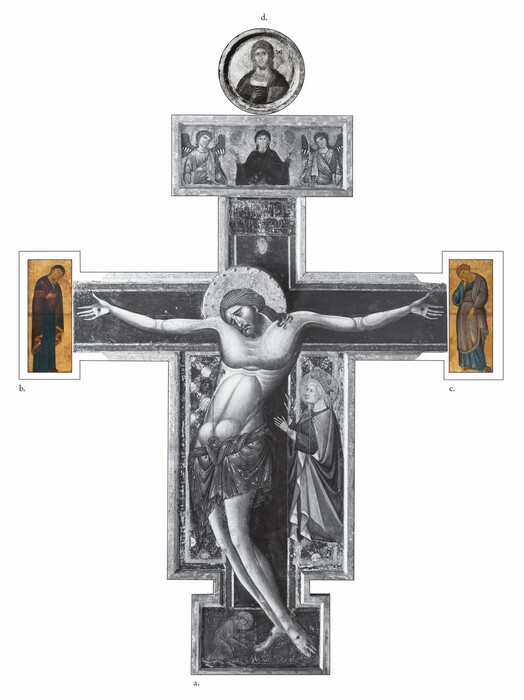

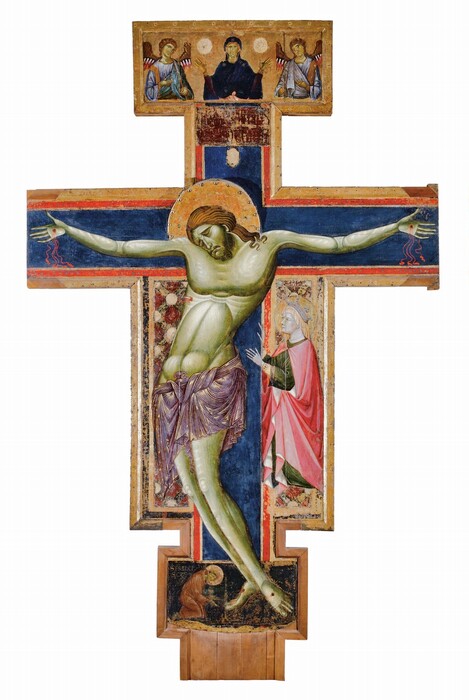

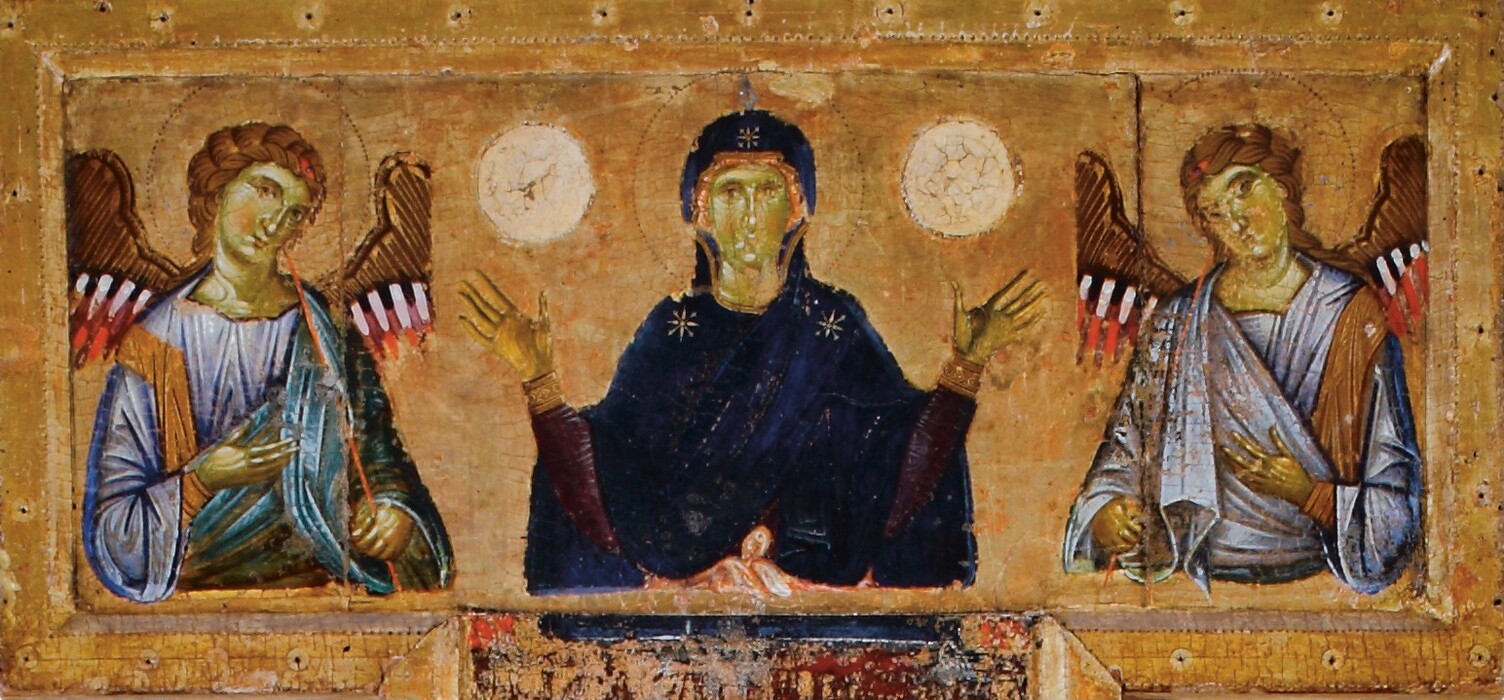

Because of their relatively large size, this panel and its companion, The Mourning Madnona, have been considered part of the apron of a painted crucifix. As their horizontal wood grain suggests, they undoubtedly formed the lateral terminals of a painting of this type, probably that belonging to the church of Santa Maria in Borgo in Bologna (now exhibited at the Pinacoteca Nazionale of that city), as Gertrude Coor was the first to recognize (see also Reconstruction). Another fragment of the work, a tondo with the bust of the Blessing Christ , was in the possession of the art dealer Bacri in Paris around 1939.

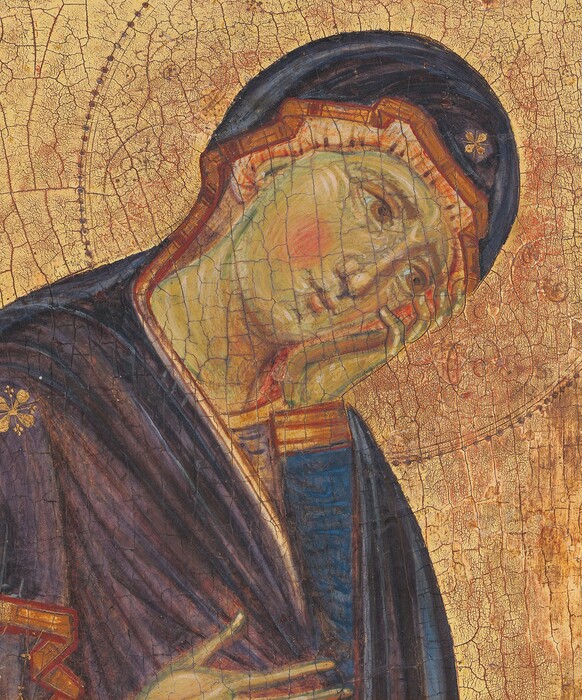

The two panels represent, respectively, the mother of Jesus and his favorite disciple in the typical pose of mourners, with the head bowed to one side and the cheek resting on the palm of the hand. As is seen frequently in Italian paintings of the late thirteenth century, Mary is wearing a purple maphorion over a blue robe, and Saint John a steel-blue garment and purple-red mantle. In publishing them (1922), Osvald Sirén noted the stylistic affinity of the two panels with the Bolognese crucifix . He inserted them in the catalog of the Master of the Franciscan Crucifixes, a painter of mixed Umbrian-Pisan culture of the second half of the thirteenth century, whose oeuvre he himself had reconstructed. For his part, Raimond van Marle (1923) considered the fragments works of an Umbrian artist of the school of the Master of San Francesco. Robert Lehman, in compiling the catalog of his father’s collection (1928), accepted Sirén’s opinion but proposed the date of c. 1250 for the two fragments. In 1929, Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà undertook a far more thorough examination of the problem of the two fragments and their stylistic affinities. Emphasizing the Umbrian component in the painter’s figurative culture, she stated that he was active in the years close to 1272 and had worked extensively in Emilia-Romagna.

While most art historians have accepted Sirén’s view and the conventional name he coined for the master, advocates of a contrary thesis have not been lacking. There are those who support the thesis that the two fragments are Pisan in derivation, or even propose Giunta Pisano as the master of the crucifix. Other art historians insist that the painter was Bolognese and exclude from his oeuvre the paintings of Umbrian provenance. Today, however, there seems no good reason to deny the common authorship of the oeuvre mainly consisting of crucifixes first assembled by Sirén, or to reject the name he attached to it, Master of the Franciscan Crucifixes.

The chronological sequence of the works attributable to the anonymous master is still under discussion. Useful clues can be deduced, however, from a comparison between some passages, such as the figure of the mourning Saint John, that frequently recur in his paintings. In my view, the pictorial treatment of the apostle in the crucifixes in the Treasury of the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, the Pinacoteca of Faenza, the bank in Camerino, and the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna not only confirm that these works were all painted by the same master but also suggest that their order of execution must have been that listed above. In the four versions of the image of Saint John, the design seems to gain in fluidity and the contours in movement, while the forms become more segmented, or ruffled, by the increasingly close-set alignment of the drapery folds. At the same time, the pose of the apostle gradually assumes the hanchement so dear to Gothic taste. These changes are present, of course, in the works of other contemporary artists and provide points of reference for the dating of our two panels. Thus, the figure of Saint John in the painting in Assisi seems to be close in style to that executed by the Master of Santa Chiara between 1253 and 1260 (crucifix in the Basilica of Santa Chiara at Assisi), while the version of the same image now in the National Gallery of Art seems more closely comparable, both in elegance of proportions and in pose, to the mourning Saint John by the Master of San Francesco, part of the painted crucifix in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia, dated 1272. The period of time indicated by these works ought also to circumscribe the years of activity of the Master of the Franciscan Crucifixes. On the other hand, the more lyrical manner of this master in comparison with the Umbrian masters cited above suggests that during the years spent in Umbria he was especially in contact with such painters as the Master of San Felice di Giano, the master of the crucifix (no. 17, unfortunately undated) in the Pinacoteca of Spoleto. His style clearly differs from that of the Bolognese followers of Giunta Pisano, and this circumstance in itself seems to rebut the hypothesis that he had been trained in the Emilian city. Yet it cannot be excluded that the artistic climate of Bologna could have stimulated successive developments in his career, especially the town’s vital and increasingly sophisticated tradition of producing miniatures for illuminated manuscripts, along with the influence of the sculpted Arca in the church of San Domenico, completed not long before the crucifix under discussion.

That the two fragments formed part of the crucifix now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna must remain a hypothesis that only proper scientific and technical analysis of the panels could corroborate. Yet the dimensions and pictorial treatment of the panels now divided among the galleries of Bologna and Washington and a private collection provide strong arguments to support the view that they originally belonged together. As for the measurements, the two panels in the Gallery, slightly cropped to the sides, are very similar in size to the upper terminal of the Bolognese crucifix . A virtual identity can also be seen in the pictorial treatment of these works. They all reveal the same search for a stylistic balance between Giuntesque formulae and a tendency towards the new needs of elegance and softness in the modeling of the figure. The similarity between the rapid brushstrokes that create the forms in the figures of the Madonna and Saint John and in the crucifix in Bologna seems to me evident. All three panels, moreover, reveal the same manner of producing relief effects by sudden flashes of light, using the same technique of applying delicate touches of white to the green underpaint preparation. The effect of this pictorial freedom and of the graceful and humanizing rendering of the figures would not fail to stimulate the Bolognese miniaturists active in the last quarter of the thirteenth century.

Technical Summary

Both this painting and its companion, Mourning Madonna, were executed on wood panels formed from at least three members with horizontal grain. The joins in both paintings line up with one another. One of the joins runs through the panels at the heights of the figures’ hips and another slightly below their knees. A third join or check runs through the top of the figure’s head in both panels, though it is more prevalent in Saint John the Evangelist. The panels were prepared with

The panels are in fair state. During a treatment by Stephen Pichetto in 1944, they were thinned and attached to secondary panels with auxiliary

now lost

now lost

Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection