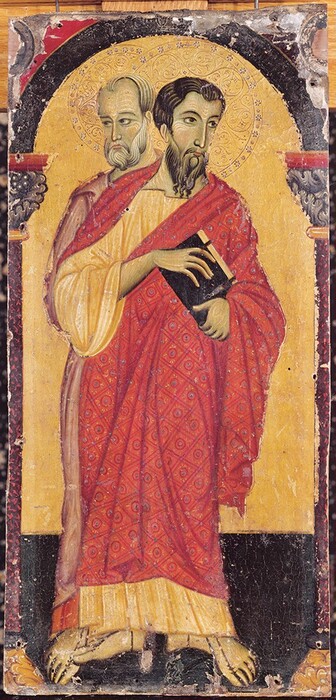

Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Saint James Minor, c. 1272

Publication History

Published online

Entry

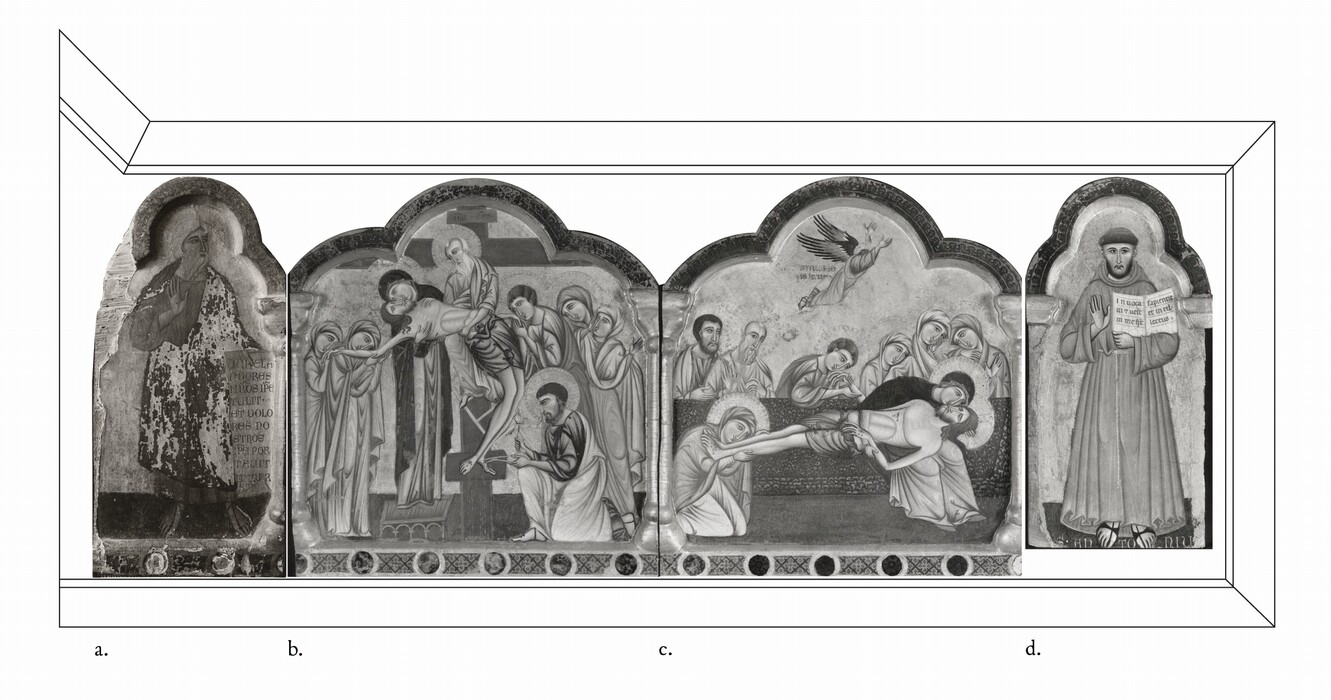

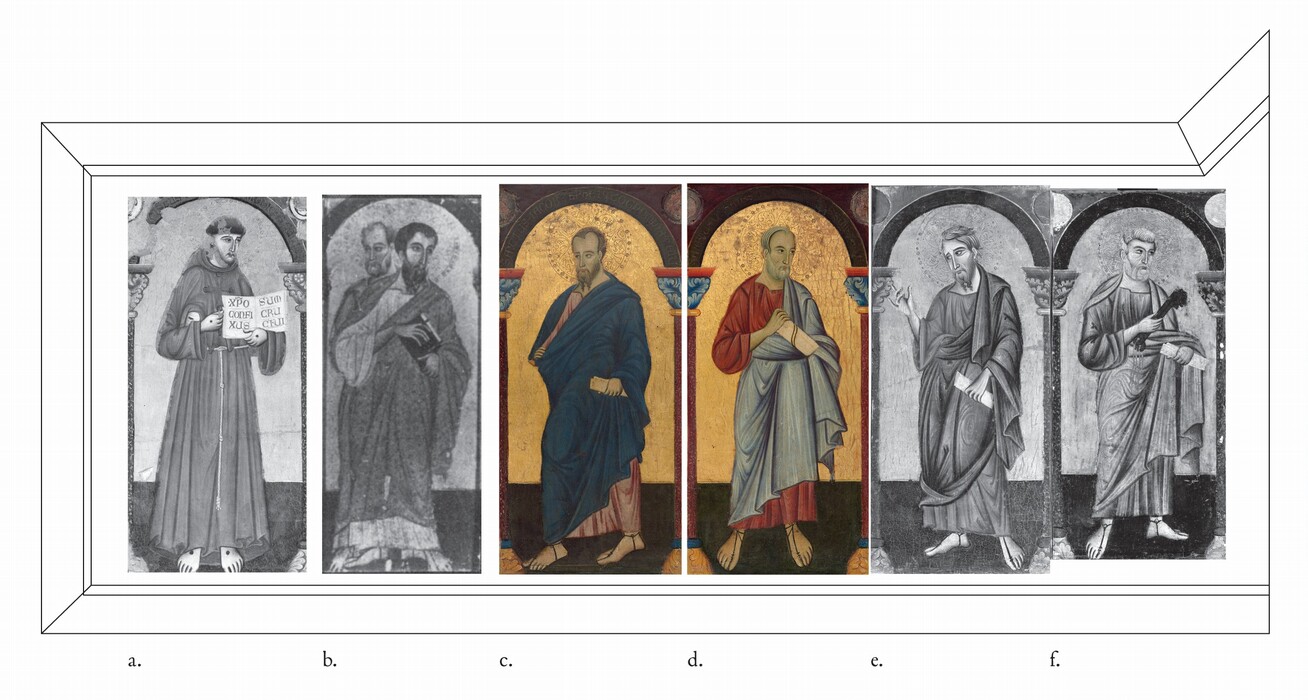

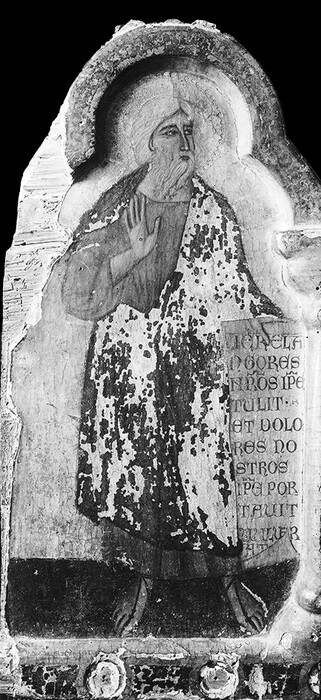

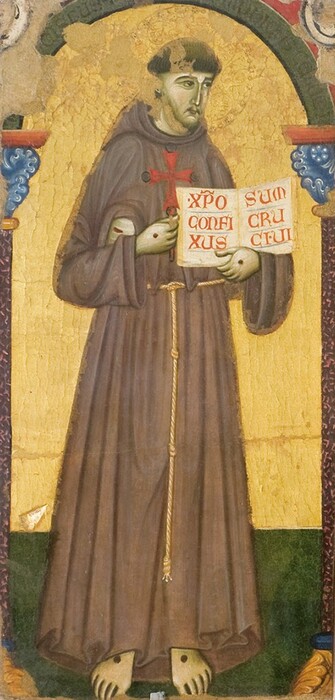

This panel and its companion, Saint John the Evangelist, originally formed part of an altarpiece painted on both sides. The side displayed to the faithful presumably showed four stories of Christ flanked by saints and prophets (see also Reconstruction), while the rear side showed the apostles and Saint Francis, full length (see also Reconstruction). Of the main side of the altarpiece, which had already been dismembered by 1793, only the components of the right part have survived, namely Prophet Isaiah (, treasury of the basilica of San Francesco, Assisi) and Deposition , Lamentation , and Saint Anthony of Padua , all three now in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia. Nothing has survived of the left part of the dossal, which perhaps showed Jeremiah (or another prophet), the counterpart of Isaiah on the other side, flanked by two other scenes of the Passion and another full-length saint, corresponding to Saint Francis on the back. The centerpiece of the dossal, probably a Madonna and Child, has also been lost. On the back of the dossal, from left to right, were Saint Francis (, now Galleria Nazionale dell’ Umbria, Perugia, no. 24); Saints Bartholomew and Simon (, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; see note 1); the two panels being discussed here from the National Gallery of Art; Saint Andrew , in the past erroneously identified with other apostles (Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia, no. 23); and Saint Peter (, formerly Stoclet collection, Brussels; acquired by the Italian State in 2002 for the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia, no. 1393). As for the lost central panel on the rear side, images of the Madonna and Child or Christ Enthroned have been proposed. To the right of the central image, the presence of six other apostles can be assumed; two of them presumably were combined in a single panel, as in the case of the Metropolitan Museum of Art painting. It is likely, lastly, that the seventh figure, the one closest to the central panel, was the apostle Saint Paul.

Both the arrangement of this series of figures, standing under arcades, and their architectural framing were inspired, as Dillian Gordon (1982) showed, by an early Christian sarcophagus formerly kept in the church of San Francesco al Prato (and now in the Oratory of San Bernardino in Perugia); it had been used as the tomb of the Blessed Egidio (Egido), one of the first companions of Saint Francis, who died near Perugia in 1262 and was greatly venerated in that city. Since the same church also housed the large painted crucifix dated 1272 likewise executed by the Master of Saint Francis and now in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia, Gordon proposed a similar date for the altarpiece as a whole—a very plausible hypothesis, even if not everyone has accepted it.

As Edward B. Garrison (1949) and other scholars recognized, the altarpiece formerly in San Francesco al Prato should be considered one of the earliest examples of the type of altarpiece classifiable as “low dossal.” Both its large size and the fact that it was painted on both sides suggest that it was intended for the high altar of the church. Its measurements cannot have diverged very much from Jürgen Schultze’s (1961) calculations (0.58 × 3.5 m). Its external profile was probably distinguished by a central gable, whether arched or triangular, placed over the lost central panel, an archaic type that was replaced as early as the last decade of the thirteenth century by the more modern form of multigabled dossals.

The question of the authorship of the work has never been seriously disputed (even though some art historians have preferred to attribute the dispersed Perugian dossal to the workshop of the Master of Saint Francis). Greater uncertainties surround its date. To elucidate the question, some preliminary reflections on the main stages in the painter’s career are needed.

Two plausibly datable works can be of help in this regard. Some have attributed to the Master of Saint Francis the Madonna and Child with an angel frescoed on the north wall of the nave in the lower church of the basilica of San Francesco in Assisi and considered it to have been executed in 1252 or just after. The cycle of narrative frescoes on both walls of the same nave, on the other hand, unanimously has been attributed to the same artist and dated to around 1260. Comparing them with the one securely dated work of the painter, the painted crucifix of 1272 in Perugia, suggests that the elegant, lively figures in the Washington panels—Saint John turning his head to the right, Saint James stepping forward to the left—are closer to the figures of the cycle with stories of Christ and of Saint Francis than to the fragmentary image of the Madonna. With its more summary design and the static poses of its figures, the latter recalls on the one hand the figurative tradition of artists active in the middle decades of the century, such as Simeone and Machilone from Spoleto, and on the other the manner of the German workshop that executed the earliest stained-glass windows in the basilica of Assisi, those of the apse of the upper church.

As new artists joined the enterprise of decorating the basilica at Assisi, however, styles rapidly changed. A transalpine artist of considerable stature must already have been at work there around 1260, introducing stylistic models more closely attuned to the Gothic taste in western Europe. Under the guidance of this master the large windows of the transept of the upper church were realized, and among the artists working at his side was the Master of Saint Francis. In the windows assignable to him, the Umbrian artist responded with great sensitivity to the poetic aspirations of his transalpine companion; he repeated some of his ideas and forms both in his own stained-glass windows and in the cycle of narrative frescoes in the lower church, combining them with the rapid gestures and the strong expressive charge characteristic of his own native Umbrian culture. Thus, the stained-glass quatrefoils on the north side of the upper church, characterized by the plastic relief given to the bodies and the harsh vigor expressed in their poses, should be considered the result of a less advanced phase in the artist’s career than the mural cycle. The panel paintings executed for the Franciscan church of Perugia must belong to later years, presumably after an interval of some duration. Here the refined elegance prescribed by the Gothic style is expressed with particular evidence in the lean figures of the two panels with stories of Christ, and also in those with single figures. What is striking in them is the aristocratic refinement of their physiognomic types, their spontaneous and improvised poses, and the capricious undulation of the borders of their mantles . Unfortunately, the few other works known to us do not offer sufficient clues to estimate how long a period of time must have elapsed between the works of the Master of Saint Francis in Assisi and those in Perugia. On the other hand, the virtual identity of the style observable in the crucifix dated 1272 and in the surviving fragments of the altarpiece suggest that the two works must have been executed close to each other in time.

Technical Summary

Both this painting and its companion, Saint John the Evangelist, were executed on a single plank of horizontal-grain wood prepared with

Stephen Pichetto “cradled, cleaned, restored, and varnished” both panels in 1944. The paint is generally in good condition on both panels, although it is less well preserved on Saint James Minor than on Saint John the Evangelist. The photographs of the paintings published by Robert Lehman (1928) show small, localized areas of

Museo del Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco, Assisi

Museo del Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco, Assisi

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Image courtesy of Former Superintendent BSAE Umbria-Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection