American Paintings, 1900–1945: Landscape with Figures, 1921

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Landscape with Figures dates from the last decade of Maurice Prendergast’s life, when he dedicated himself almost exclusively to creating variations on the theme of group leisure in waterfront park settings. The artist depicted crowds at play throughout his career, having previously produced dappled watercolors of people gathered at New England coastal resorts, promenading along Venice’s canals, and enjoying New York’s Central Park. After his 1907 trip to France, where he studied the paintings of Paul Cézanne, both Prendergast’s style and his interest in representing specific locales changed. The artist later wrote to the critic Walter Pach that Cézanne’s work had “strengthened and fortified me to pursue my own course.” Indeed, Prendergast absorbed Cézanne’s use of broken brushwork, emphasis on the contour of forms, and layering of color to create his own vision. After 1914 he incorporated into his modernist idiom thematic aspects of the work of Giorgione, Nicolas Poussin, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Paul Gauguin, producing scenes of classicized women in generalized landscapes based loosely on the coastal parks surrounding Boston. These last paintings, Landscape with Figures among them, have been described by scholars as idylls that refer to a world removed from industrialization, technological advance, materialism, and war.

Formally, Landscape with Figures exemplifies Prendergast’s large, late oils, which are consistent in composition and paint application. Horizontal banding, in which the frieze of figures in the park, the water zone, and the sky are stacked one on top of the other, contributes significantly to the overall flatness of the picture. The composition, although containing many disparate elements, is unified by several trees extending from the lower into the upper registers and by the decorative patterning of the repeating circles of heads, bodices, hats, parasols, rocks, and the sun. The painting is also held together by its lively brushwork. Prendergast daubed, stippled, and dragged the paint, primarily muted reds, yellows, blues, and greens, to create a syncopated effect. Because he often skipped his brush over the heavily textured surface, which he had built up over time, Prendergast never completely obscured the paint layers beneath. Art historians have noted that this technique lends his paintings a sense of mystery and unreality. In Landscape with Figures this can be seen most easily in the lower right, where the bottom half of a woman in a red dress appears to be spectral.

Nancy Mowll Mathews has argued persuasively that Prendergast’s idylls served as elegies for turn-of-the-century leisure activities, such as group excursions by train and long resort holidays. These traditions disappeared in the face of individualized automobile travel and limited vacation time, as well as a world war that destroyed belief in an increasingly civilized society. According to Mathews, Prendergast retreated from reality in his late paintings by monumentalizing and making timeless the group leisure he and his audience no longer experienced. Significantly, Landscape with Figures belongs to a subset of Prendergast’s idylls that features a low or setting sun . The yellow light of the fading day that so forcefully falls on and between the legs of the women in Landscape with Figures suggests the waning of the type of leisure Prendergast valued.

In December 1923 the Corcoran Gallery of Art awarded Prendergast the Third William A. Clark Prize of one thousand dollars and the accompanying Corcoran Bronze Medal for Landscape with Figures, which he had sent to the Ninth Biennial Exhibition in a gilded frame probably made by his brother, Charles. The jury that honored Prendergast consisted of the artists Gari Melchers (chairman), Lilian Westcott Hale, Rockwell Kent, Ralph Elmer Clarkson, and Daniel Garber. The award was one of the few official recognitions of this kind that Prendergast received in his lifetime (the other being a bronze medal at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, in 1901). When he received notice of the honor, he supposedly remarked to his brother: “I’m glad they’ve found out I’m not crazy, anyway.” He wrote to the Corcoran’s director, “I shall prize it very much.”

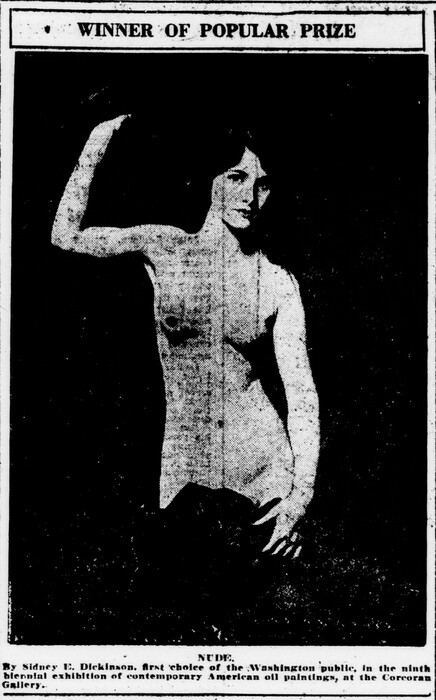

In truth, Prendergast had been receiving positive recognition for his work from progressive critics and collectors since the 1913 Armory Show had exposed Americans to European modernism, but reviews in the more conservative capital city were mixed. Many admired the Corcoran’s canvas as “a pleasing example of futurism,” but others agreed with Leila Mechlin of the Washington Star, who complained that the painting “brings to mind nothing other than an old-fashioned hooked rug, or a composition in cremel worsteds, it is an uneasy composition at that, and one wonders. But one almost always does wonder at the decision of prize juries.” Exhibition visitors voting for the popular prize that year picked, by a wide margin, Sidney E. Dickinson’s Nude, a realistic painting of a bare-breasted model . Landscape with Figures received only one vote.

In contrast to the ambivalent reception by the District’s art community, the Corcoran sought acquisition of Landscape with Figures just two days after the biennial opened. The staff most likely concurred with the jury of Prendergast’s artist peers, who, as director C. Powell Minnigerode explained, valued the painting’s “technical quality, originality, and execution.” Prendergast agreed to sell Landscape with Figures to the gallery at a one-third discount, for, he wrote, “I prefer Washington to have it.” The sale made the Corcoran the first public institution to recognize Prendergast’s important contribution to American art; previously, individual collectors such as John Quinn, Lillie P. Bliss, Dr. Albert C. Barnes, and Duncan Phillips were his major patrons. Other museums began purchasing Prendergast’s work only after he died, just two months after the Corcoran’s acquisition of Landscape with Figures.

Technical Summary

The painting was executed on a plain-weave, medium-weight canvas and was lined with a fiberglass fabric using a wax/resin adhesive. A smooth, thick, grayish-white ground appears to have been commercially prepared because the ground extends onto the tacking margins and was dry when the canvas was stretched. Furthermore, the tacking margins are intact, suggesting that the painting must be very close to its original dimensions, although the stretcher is a replacement. However the top tacking edge has a considerable amount of paint on it, suggesting that the artist began painting in a slightly larger format and later restretched the canvas to its present size. The signature and date on the reverse are no longer visible because they were covered up by the lining. The inscription was transcribed and photographed when the work was lined, but the image can no longer be located.

The artist’s technique is distinctive. He applied paint freely in a series of layers over previously dried layers of paint, eventually resulting in a very thick accumulation of paint in most areas. His technique of repeatedly dragging pasty paint across the surface of base layers has resulted in a very convoluted surface texture. By continually defining his forms with dark outlines the artist obtained a stained-glass effect. Many of the final touches of paint over this thick and largely opaque buildup were executed in deep reds and dark purples in thin, transparent paint. The work is coated with a clear synthetic resin varnish coating with a medium gloss.

According to the Corcoran’s conservation files, at some point L. J. Kohlmar had attached a lead-primed artist canvas as a lining to the reverse of the original canvas using a paste/glue adhesive. In 1964 Russell Quandt removed this lining and replaced it with a fiberglass fabric lining adhered with a wax/resin adhesive. Although Quandt does mention having inpainted the work in this treatment, recent ultraviolet examination shows little retouching. Quandt also probably removed the varnish and replaced it at this time. In 1966 Quandt surface-cleaned and revarnished the painting. Presently the appearance of the painting is quite good, although the extreme thickness of the paint has led to wide mechanical cracks and cupping.

Butler Institute of American Art

Butler Institute of American Art