Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Tavern Scene, early 1660s

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Within the dark confines of a spacious tavern country folk have gathered to pass the evening hours warming themselves by the fire, playing cards or backgammon, or just kibitzing while enjoying the soothing effects of tobacco and beer. The trees silhouetted against the moonlit sky, seen through the leaded-glass windows, situate the tavern in a rural setting. One senses that this scene is a recurring evening ritual, in which residents from the local community play out familiar roles night after night.

Much of the appeal of this small painting comes from the sense of atmosphere that helps unify the composition. One can imagine the quiet din of conversation within the dark recesses of this smoke-filled space. Light from various sources—the fire, the candle attached to the hearth, and the hidden candles on the tables—gives a warmth to the scene that is reinforced by the attitudes and expressions of the figures themselves.

Adriaen van Ostade, perhaps more than any other Dutch artist, devoted himself to the depiction of the lower echelons of Dutch society. Almost certainly influenced by Brouwer, Adriaen in his early years, Van Ostade initially executed images of peasant life that were far from flattering. By the 1660s, when he executed this small panel, his images had changed considerably. Instead of behaving raucously in taverns that look more like barns than public structures, the people here enjoy their leisure hours with exemplary deportment. Despite the presence of beer, tobacco, playing cards, and a backgammon game, none of these men has succumbed to vices so often associated with those who have yielded to sensual pleasures: no one has passed out, vomited, or threatened a fellow cardplayer with a knife or jug. The tavern itself is substantial and well kept, with a large fireplace, immaculately clean leaded windows, and sturdy ceiling beams.

As the character of his peasant subjects changed during the course of Van Ostade’s career, so did his style of painting. By the 1660s his technique had become more refined as he sought to develop a more subtle use of light and dark. This evolution in style might have developed in conjunction with his extensive work in etching during the 1640s and 1650s. Many of his etchings of interior scenes, for example, explore the subtle effects of various light sources to establish mood. Certainly the smallness of this painting and the delicacy of his touch bring to mind the scale and character of his etchings.

Because the last digit of the date is illegible, it is not certain when during the 1660s this scene was painted. The general disposition of the interior, however, is comparable to Van Ostade’s 1661 Peasants in an Interior (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). Not only are the architectural elements similar, but the inn’s patrons are likewise organized into two groups, one situated before the hearth and the other around a table set in the background beneath the leaded-glass windows. It thus seems probable that this work also dates from the early 1660s.

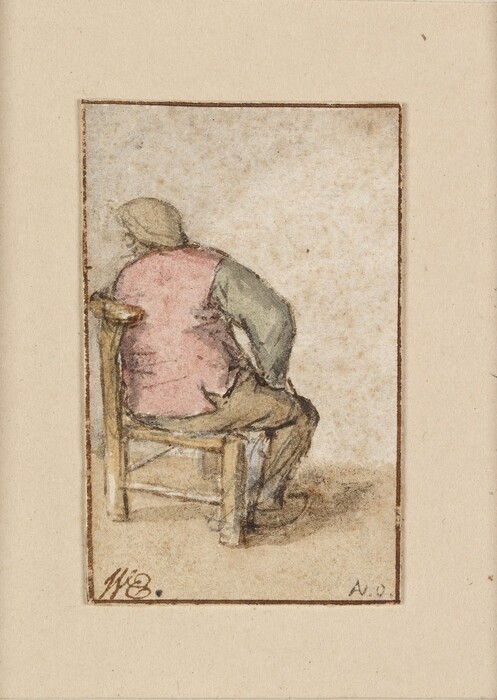

Van Ostade must have composed his scenes with the aid of individual figure studies, of which many exist. Although no such study from the 1660s matches exactly any of the figures in this composition, a watercolor from the 1670s, part of a series by Van Ostade in which he recorded earlier studies, depicts the seated man before the fireplace .

Technical Summary

The cradled panel support is composed of a single oak board with the grain running vertically. There is a slight convex warp. Dendrochronology estimates a felling date of 1650 for the tree and a period of 1655–1670 for the panel use.[1] A thin, off-white ground layer prepared the panel to receive thin paint layers whose low-covering power left the wood grain visible.

Moderate flaking in the past has occurred overall, and damage across the center of the painting has left a series of seven horizontal losses in the hat of the man farthest to the left and in the cardplayers (at the same height), as well as a vertical scratch through the arm of the central standing figure. The figures are slightly abraded, although the faces are free of loss or abrasion. Discolored varnish and old inpaint were removed when the painting was treated in 1978. The ground is somewhat crizzled, an effect that has transferred to the paint, making it difficult to saturate the paint and achieve an even coating of varnish. Many layers of varnish were applied in 1978 in an effort to achieve a satisfactory finish. By 2012, these layers of varnish had turned hazy and were no longer saturating the paint. Therefore, the varnish and inpainting were removed and replaced with new inpainting and a thinner layer of varnish..

[1] Dendrochronology by John Fletcher, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, Oxford University (see report dated November 16, 1979, in NGA Conservation files).

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford