Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: View of Dordrecht from the Dordtse Kil, 1644

Publication History

Published online

Entry

On a calm day with an overcast sky, a sailboat stops across from the city of Dordrecht to take on passengers from a rowboat. This sailboat, heavily laden with travelers, served as a ferry, one of a number of types of boats that transported people along the many inland waterways of the Dutch Republic. In the foreground another ferry—a rowboat filled with men, women, and children—heads toward Dordrecht across a wide body of water.

Van Goyen has situated the viewer southwest of Dordrecht on the bank of the Dordtse Kil. The spit of land on the left, on which the fisherman tends to his traps, marks the juncture of the Dordtse Kil with a larger river, the Oude Maas. The sailboat, which is behind this spit of land, is on the Oude Maas at the point where it is joined by the Dordtse Kil and begins to flow west, away from Dordrecht.

Dordrecht was an old and extremely important city in the Dutch Republic. By 1644, when Van Goyen painted this view, it had long since been a major mercantile center. Its importance grew as a result of its favorable geographic situation at the juncture of a number of major inland waterways that connected with the German and southern hinterlands. The conservative character of the city’s rich patrician class was reinforced by the formidable presence of the Dutch Reformed Church that resulted from the victory of the orthodox Calvinists, known as the Counter-Remonstrants, over the more moderate Remonstrants at the Synod of Dordrecht in 1618–1619. The Groote Kerk, the large cathedral with the unfinished spire rising in the distance, was the real and symbolic center of the church’s power in the city.

Van Goyen traveled frequently throughout the Netherlands during his long and productive career. On these trips he would fill sketchbooks with scenes that he later expanded into paintings executed in his studio. Working from such sketches he painted more than twenty such views of Dordrecht from the southwest between 1644 and the early 1650s. These paintings contain, in various combinations, many of the same compositional elements: the passenger sailboat, rowboats, the fisherman, and boats sailing along the distant shore, as well as buildings associated with the city’s profile itself. Without exception, Van Goyen featured the activities of the ferryboat loading and unloading passengers as it passed the juncture of the Oude Maas and the Dordtse Kil. He seems to have been intrigued as much by the activities associated with the site as by the dramatic view of Dordrecht that it offered.

This painting comes at the beginning of the series and is exceptional in the extraordinary stillness of the water. Reflections of the boats, buildings, and even the sky create subtle patterns across its surface. Van Goyen suggests the translucency of the water in the immediate foreground by allowing the ocher-colored ground to be visible through the thin brownish glazing on top of it. This painting technique, in which one looks through the surface to an underlying layer, parallels the experience of viewing water in nature.

The thinly painted distant view of Dordrecht is conceived in these same terms. The softly undulating tones and suggestive brushwork create the sense that the buildings, rather than being sharply defined solid masses, are enveloped in a misty shroud. This work, however, is not a pure “tonal” painting such as those executed by Van Goyen in the late 1630s and early 1640s; instead, it marks a transition to his later “classical” style. The sky is relatively densely painted, and areas of blue peek through the cloud cover. Touches of local color—blues, reds, and pinks—appear on the clothes of the figures.

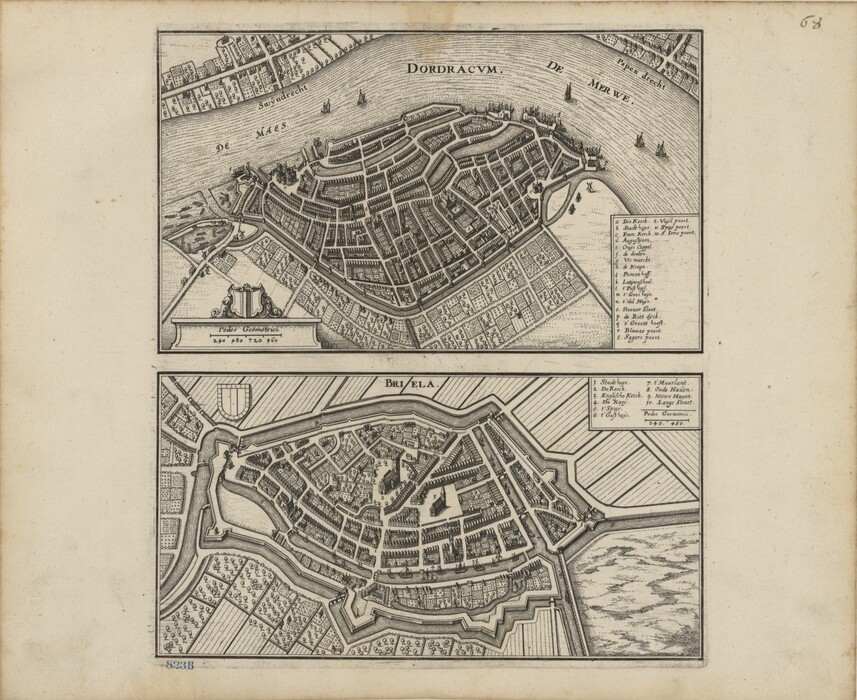

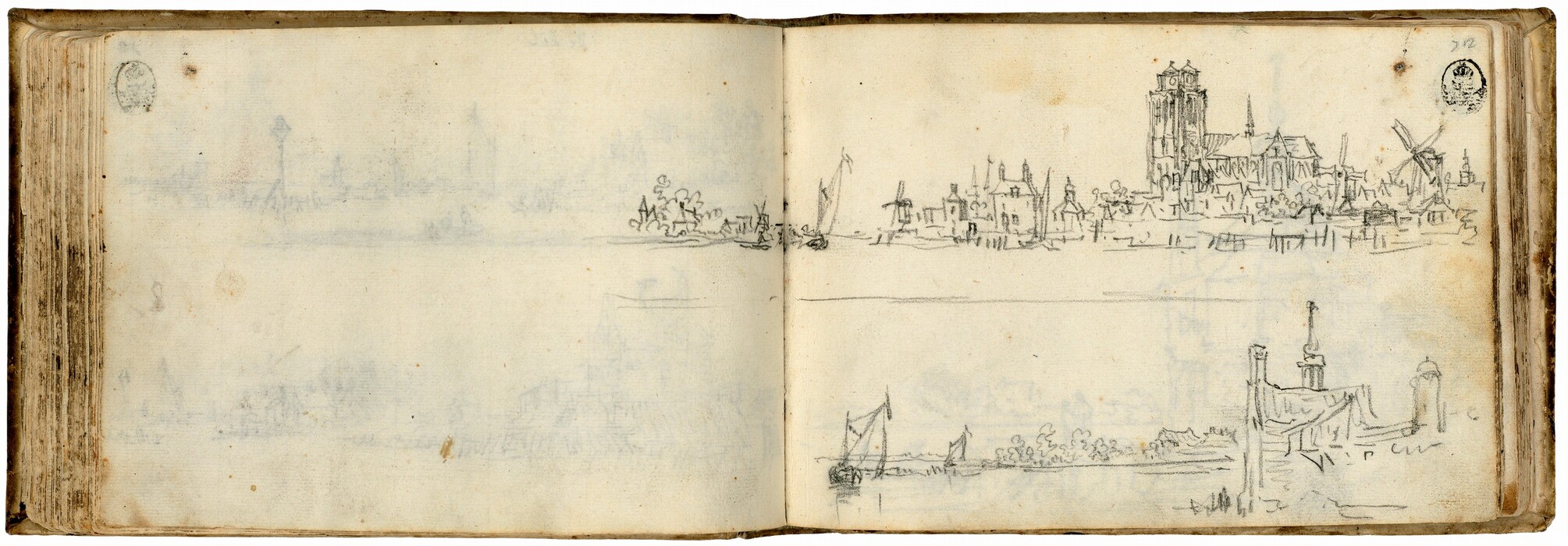

Many elements of Dordrecht’s architecture in this painting can be found on contemporary maps. The windmills to the right, the walled bulwark before the Groote Kerk, the ships clustered at the Vuylpoort beyond the bulwark, and the round bastion at the south bank of the Sagerspoort, for example, are all visible on the 1646 bird’s-eye-view map of Dordrecht in M. Merian’s Neuwe Archontologia Cosmica (Frankfurt am Main, 1646). The windmill on the bastion near the north end of the Nieuwe Haven, visible on the map, is seen here along the distant left edge of the Dordrecht coastline. While Van Goyen has accurately recorded the general disposition of the topographical elements, he has exaggerated the distances between them. If one compares this scene with a drawing of Dordrecht found in a sketchbook Van Goyen made around 1648 , one sees that the architectural elements were in reality more compactly grouped when seen from that vantage point. Van Goyen sought to give the view a panoramic character by stretching out the topographical elements, so that the eye scans across the horizon instead of being thrust into depth, and he deliberately situated the large sailboat in the foreground over the natural vanishing point of the scene. Through compositional decisions that minimize the effects of deep recession into space, Van Goyen thus sought to enhance the peaceful nature of the scene, encouraging his viewer to partake of the quiet mood engendered by the delicate atmospheric effects.

Technical Summary

The support is a thin panel composed of three horizontally grained boards of equal width joined horizontally. The support has been mounted onto another thin panel and cradled, with a slight dislevel along the upper join of the original panel. Paint is applied over a thin off-white ground with low, fine brushmarking, in thin semitransparent darks and thicker opaque lights.[1] The sky, the water, and the trees and buildings along the horizon were rapidly painted in an initial stage working wet-into-wet. In a later stage the primary boats and figures were sketched and painted over the dry paint of the water.

Small amounts of inpaint cover the panel joins, edges, and areas of slight abrasion. In a prior restoration, four undamaged areas in the central sky were overpainted to make the clouds appear denser. The painting has not been treated since its acquisition by the National Gallery of Art.

[1] The pigments were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) by the NGA Scientific Research department (see report dated August 4, 1982, in NGA Conservation department files).

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Library of Congress, Washington, Rare Book and Special Collections Division

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Library of Congress, Washington, Rare Book and Special Collections Division

Photo: Herbert Boswank, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden