Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664

Publication History

Published online

Entry

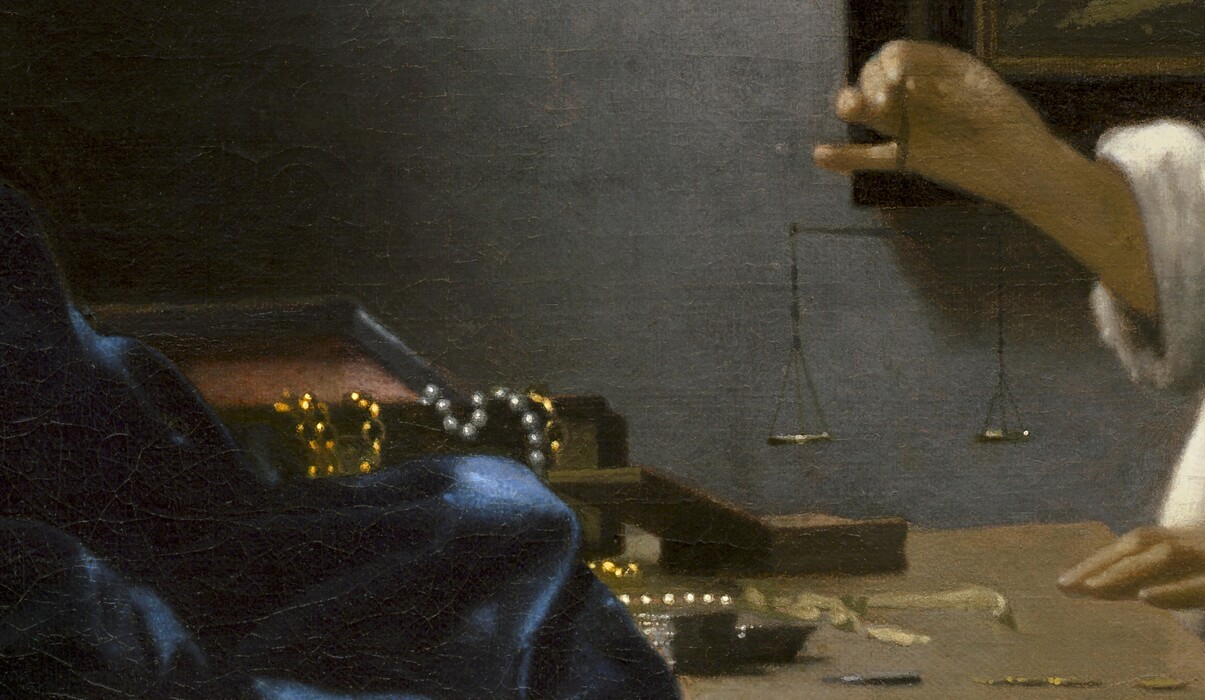

The young woman standing before a table in a corner of a room gazes toward the balance she is holding gently in her right hand. As though waiting for the delicate modulations of the balance to come to rest, she stands transfixed in a moment of equilibrium. She is dressed in a blue morning jacket bordered with white fur; seen through the parting of her jacket are vivid stripes of yellow and orange, perhaps ribbons or part of her bodice. Her white cap falls loosely to either side of her neck, framing her pensive yet serene face. Diffused sunlight, entering through an open window before her, helps illuminate the scene. The light, warmed by the orange curtain, flows across the gray wall and catches the fingers of the woman’s right hand and the balance before resting on her upper figure.

Behind the woman looms a painting of the Last Judgment, which acts as a compositional and iconographic foil to the scene before it. The Last Judgment, its proportions echoing those of the overall painting, occupies the entire upper right quadrant of the composition. Its rectangular shape establishes a quiet and stable framework against which Vermeer juxtaposes the figure of the woman, whose white cap and blue morning jacket contrast with the dark painting. Her figure is aligned with the central axis of the Last Judgment: her head lies at the middle of its composition, directly beneath the oval mandorla of the Christ in majesty. Her right hand coincides with the lower corner of the frame, which happens also to be the vanishing point of the perspective system. Her head and the central gesture of her hand are thus visually locked in space, and a seeming moment of quiet contemplation becomes endowed with permanence and symbolic associations.

The visual juxtaposition of the woman and the Last Judgment is reinforced by thematic parallels: to judge is to weigh. As Christ sits in majesty on the Day of Judgment, his gesture, with both arms raised, mirrors the opposing direction of the woman’s balance. His judgments are eternal; hers are temporal. Nevertheless, the woman’s pensive response to the balance suggests that her act of judgment, although different in consequence, is as conscientiously considered as that of the Christ behind her. What then is the thematic relationship between her act and the painting on the wall behind her?

This question has been asked time and again, and, indeed, the actual nature of her act and its significance have been variously interpreted. Most earlier interpretations of this painting focused on the act of weighing and were premised upon the assumption that the pans of the woman’s balance contain certain precious objects, generally identified as gold or pearls. Consequently, until recently the painting had been alternately described as the Goldweigher or the Girl Weighing Pearls.

Microscopic examination, however, has revealed that the apparent objects in the scales are painted in a manner quite different from the representation of gold or pearls found elsewhere in this painting . The highlights in the scale certainly do not represent gold, for they are not painted with lead-tin yellow, as is the gold chain draped over the jewelry casket. The pale, creamy color is more comparable to that found on the pearls, but while the point of light in the center of the left pan of the balance looks initially like a pearl, Vermeer’s technique of rendering pearls is different. As may be seen in the strand of pearls lying on the table and in those draped over the jewelry box, he paints pearls in two layers: a thin, underneath (grayish) layer and a superimposed highlight. This technique permits him to depict their specular highlights and at the same time to suggest their translucent and three-dimensional qualities. In the band of pearls draped over the box, the size of the pearl (the thin, diffused layer) remains relatively constant although the highlights on the pearls (the thick, top layer) vary considerably in size according to the amount of light hitting them. The highlight in the center of the left pan is composed of only one layer—the bright highlight. Lacking the underlayer, the spot is not only smaller but also less softly luminescent compared to the pearls. The more diffused highlight in the center of the right pan is larger, but it is not round and has no specular highlight. These points thus appear to be reflections of light from the window rather than objects unto themselves. Reinforcing the sense that the scales are empty is the fact that the pearls and gold on the boxes and table are bound together and none lie on the table as separate entities as though waiting to be weighed and measured against one another.

Even so, the jewelry boxes, strands of pearls, and gold chain on the table must be considered in any assessment of this painting’s meaning. As riches they belong to, and are valued within, the temporal world. They have been interpreted in the past as temptations of material wealth and the woman as the personification of Vanitas. Pearls, however, have many symbolic meanings, ranging from the purity of the Virgin Mary to the vices of pride and arrogance. As the woman concentrates on the balance in her hand, her attitude is one of inner peace and serenity. The psychological tension that would suggest a conflict between her action and the implications of the Last Judgment does not exist.

Although the allegorical character of Woman Holding a Balance differs from the more genrelike focus of comparable paintings by Vermeer of the early to mid-1660s, the thematic concerns underlying this work are similar: one should lead a life of temperance and balanced judgment. Indeed, this message, with or without its explicit religious context, is found in paintings from all phases of Vermeer’s career and must represent his profound beliefs about the proper conduct of human life. The balance, the emblem of Justice and eventually of the final judgment, would seem to denote the woman’s responsibility to weigh and balance her own actions, a responsibility reinforced by the juxtaposition of her head over the traditional position of Saint Michael in the Last Judgment scene. Correspondingly, the mirror, placed near the light source, and directly opposite the woman’s face, was commonly referred to as a means of self-knowledge. As Veen, Otto van wrote in an emblem book Vermeer certainly knew, “a perfect glasse doth represent the face, Iust as it is in deed, not flattring it at all.” In her search for self-knowledge and in her acceptance of the responsibility of maintaining the balance and equilibrium of her life, the woman would seem to be aware, although not in fear, of the final judgment that awaits her. Indeed, in the context of that pensive moment of decision, the mirror also suggests the evocative imagery of 1 Corinthians 13:12: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” Vermeer’s painting is thus a positive statement, an expression of the essential tranquility of one who understands the implications of the Last Judgment and who searches to moderate her life in order to warrant her salvation.

The character of the scene conforms closely to Saint Ignatius of Loyola’s recommendations for meditation in his Spiritual Exercises, a devotional service with which Vermeer was undoubtedly familiar through his contacts with the Jesuits. As Cunnar has emphasized, Saint Ignatius urged that, prior to meditating, the practicer first examine his conscience and weigh his sins as though he were standing before God on Judgment Day, and then “weigh” his choices and choose a path of life that will allow him to be judged favorably in a “balanced” manner.

I must rather be like the equalized scales of a balance ready to follow the course which I feel is more for the glory and praise of God, our Lord, and the salvation of my soul.

The many different interpretations of this painting that have appeared over the years, nevertheless, are a reminder of how cautious one must be in proposing a given meaning for this work. In addition to questions concerning the contents of the balance, there has been speculation as to whether the woman is pregnant or whether her costume reflects a style of dress in fashion during the early to mid-1660s, when this painting seems to have been executed. If she is pregnant, does her pregnancy have consequence for the interpretation of the painting? Is she, as some have suggested, a secularized image of the Virgin Mary, who, standing before the Last Judgment, would assume her role as intercessor and compassionate mother? Cunnar has argued, for example, that the image of a pregnant Virgin Mary contemplating balanced scales would have been understood by a Catholic viewer as referring to her anticipation of Christ’s life, his sacrifice, and the eventual foundation of the Church. Such theological associations were made in the seventeenth century and may have played a part in Vermeer’s allegorical concept.

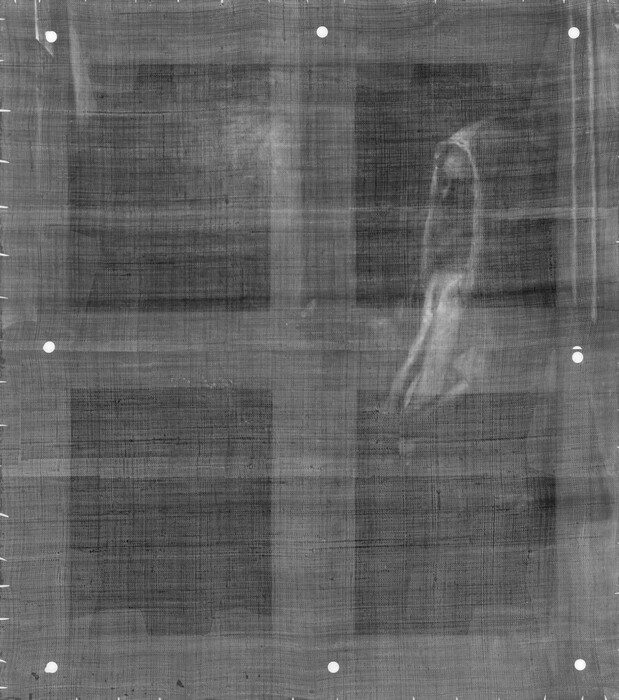

This painting offers one of the most glorious examples of Vermeer’s exquisite sense of balance and rhythm from the early to mid-1660s. The woman, her right hand gently holding the scale, is poised with her small finger extended, which gives a horizontal accent to the gesture. The left arm, gracefully resting on the edge of the table, closes the space around the balance and establishes an echo to the gentle arch of boxes, blue cloth, and sunlight sweeping down from the other side. The scales themselves, perfectly balanced but not symmetrical, are situated against the wall in a small niche of space created especially for them. Although no pentimenti are visible in the X-radiograph [see X-radiography], an infrared reflectogram reveals that the balance was enlarged and lowered. Vermeer has also taken the liberty of raising the bottom left edge of the picture frame behind the woman to allow sufficient room for the balance. Throughout, his interplay of verticals and horizontals, and of both against diagonals, of mass against void, and of light against dark, creates a subtly balanced but never static composition.

Restoration performed in 1994 provides further insights into Vermeer’s extraordinary sensitivity to light and color . With the removal of old inpainting and discolored varnish, one can, for example, more fully appreciate the delicate flesh tones in the woman’s face and the subtle modeling of the blue robe on the table. Most startling, however, was the discovery of extensive overpaint covering the black frame of the Last Judgment. The gold trim now revealed creates an accent in the upper right that visually links with the yellow curtain and the yellow and deep-orange accents on the woman’s costume, thereby restoring Vermeer’s original, and more dynamic, compositional intent. At the same time, the X-radiograph reveals that the tacking margins had been opened out and overpainted. With the removal of this overpaint, the image is now smaller than it had previously appeared, and its size reflects Vermeer’s original intention.

The degree of Vermeer’s sensitivity can best be illustrated by comparing this scene with a close counterpart by Hooch, Pieter de, A Woman Weighing Gold . Although De Hooch probably painted this scene in the mid-1660s after he left Delft for Amsterdam, it is so similar to Vermeer’s that it is difficult to imagine that they were painted without knowledge of each other or of a common source. Nevertheless, the refinements and mood of the Vermeer are lacking in the De Hooch. The woman in De Hooch’s painting is not gazing serenely at her scales; she is actively engaged in placing a gold coin or weight into one of the pans. By her active gesture she separates herself from the quiet rhythms and geometrical structure of the room.

Woman Holding a Balance has a distinguished provenance that can be traced in a virtually unbroken line back to the seventeenth century. The enthusiastic descriptions of the work in sales catalogues as well as in critics’ assessments attest to its extraordinary appeal to each and every generation. Perhaps the most fascinating early reference to this work comes from the first sale in which it appeared, the Dissius sale in Amsterdam of 1696. It is the first painting listed in that sale, which included twenty-one paintings by Vermeer, and is described in the following terms: “A young lady weighing gold, in a box by J. van der Meer of Delft, extraordinarily artful and vigorously painted.”

The protective box in which Woman Holding a Balance was framed was probably related to the painting’s special thematic character. Much as with the boxes that Dou, Gerrit occasionally placed around his paintings, one would be able to see Woman Holding a Balance only after opening two little doors attached to the box in which it was placed. The painting, thus, was not conceived as a work to be viewed every day, as one passed back and forth while occupied with mundane activities. Rather, the decision to contemplate this painting would have been consciously made, reserved for those quiet moments when one yearns for inner peace and is in search of spiritual guidance. Upon encountering this radiant image after opening these doors, the viewer’s eye, located directly opposite the vanishing point, would have been drawn to the symbolic core of the composition. The experience would have been a private one, a timeless moment for both visual and spiritual enrichment as one contemplated the allegorical themes of balance and harmony that underlie this work. That the painting was listed first in the sale and contained in a protective box indicates the extraordinary value placed on this work, an appreciation that has never diminished.

Technical Summary

The original support is a very fine, tightly woven fabric. When the painting was lined, the format was enlarged about one-half inch on all sides by opening out and flattening the tacking margins. The composition was extended by overpainting these unpainted edges. Regularly spaced tacking holes and losses in the ground layer along the folds of fabric bent over the original stretcher confirm that these smaller dimensions were the original format.

A moderately thick, warm buff ground is present overall, and extends onto the tacking margins. Examination has not shown evidence of an underdrawing but does show a brown painted sketch describing the forms with fine lines and indicating shadows with areas of wash. Microscopic examination shows a pinhole in the back wall near the balance, where the artist probably pinned strings to establish the orthogonals of the perspective system. Both the ground color and the brown sketch influence the final image, the ground color warming the thinly painted flesh tones and hood and the brown sketch contributing shadows to the blue jacket. Vermeer blended finely ground, fluid paint with imperceptible brushstrokes and added rounded, thicker touches to create specular highlights. He softened some contours by overlapping paints and suggested others by leaving a thin line of brown sketch between two edges. No pentimenti are visible in the x-radiograph; an infrared photograph reveals a change in the position of the balance.

Small losses are found in the figure, small areas of abrasion in the dark passages. Discolored inpainting and varnish were removed in 1994. During this treatment, black overpaint covering the frame of the Last Judgment on the wall behind the woman was removed, revealing two vertical bands of yellow paint along the right side of the frame. Overpaint that had been applied along the opened-out tacking margins when the painting was restretched on a larger stretcher has been removed. The painted image, now smaller, reflects Vermeer’s original intention.

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Joanna Dunn based on conservation reports by David Bull, Melanie Gifford, Melissa Katz, and Kay Silberfeld

April 24, 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection

Photo: bpk, Berlin / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie

Photo: bpk, Berlin / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie