Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Girl with a Flute, c. 1669/1675

Entry

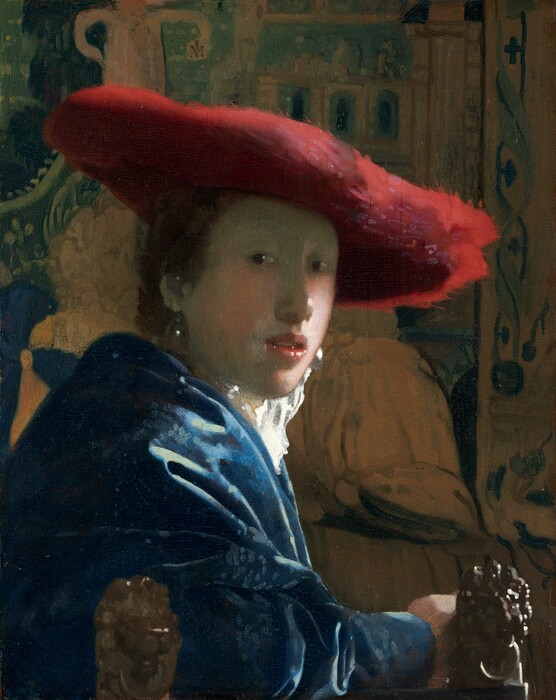

Gazing at the viewer from beneath a striking hat that casts a strong shadow over much of her face, the subject of Girl with a Flute occupies a shallow space defined by a patterned tapestry and a chair with lion-head finials. She rests her left arm on a ledge in the foreground and holds a recorder loosely in that hand. She wears a fur-trimmed jacket known as a jak or manteltje, a garment commonly found in domestic genre paintings by Gerard ter Borch the Younger, Gabriel Metsu, Frans van Mieris, Johannes Vermeer, and others from the 1650s through the early 1670s. (Similar jackets are worn in Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing.) Like the feathery, red beret in Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat, the curious hat in Girl with a Flute has no exact equivalent in paintings of the period. It appears to have been inspired by Chinese hats constructed of woven bamboo, but it has been modified by the addition of a gray, white, and black striped fabric covering, presumably to enliven its appearance.

When Girl with a Flute came to the National Gallery of Art in 1942 as part of a massive donation from Joseph Widener (1871–1943) and his late father, P. A. B. Widener (1834–1915), the work was hailed as the museum’s fifth painting by Vermeer. The painting had been discovered in 1906 by Abraham Bredius, director of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, in the Brussels collection of Jonkheer Jean de Grez. Bredius found the painting “very beautiful,” and it was exhibited at the Mauritshuis in the following year to great acclaim. In 1911, after De Grez’s death, the family sold the painting, and it soon entered the distinguished collection of August Janssen in Amsterdam. After this collector’s death in 1918, the painting made its way to the New York dealer M. Knoedler & Co., which sold it to Joseph Widener. On March 1, 1923, the Paris art dealer René Gimpel recorded the transaction in his diary, commenting, “It’s truly one of the master’s most beautiful works.”

Yet despite its enthusiastic initial reception, the painting’s attribution was soon called into question by scholars, who noted the painting’s many compositional weaknesses. The figure is static, posed nearly frontally, and leans heavily on the ledge in the foreground with no sense of breath or incipient motion. There is an awkward disparity in the proportions of her arms and only the vaguest sense of a body beneath her fur-trimmed robe. Her hat, left shoulder, and right hand are cut abruptly by the edges of the panel. The flute she holds (actually a recorder) is curiously undefined and seems inaccurately rendered. Rather than venturing an oblique glance from over her shoulder, a detail that characterizes Vermeer’s other single-figure depictions of young women, she looks at us straight on with little attempt at intrigue or beguilement. Even the chair finial and background tapestry are indifferently rendered—the brushwork is blocky and does little to create a sense of form or volume.

Similarities in scale, subject matter, and wood panel support have caused some scholars to consider Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute as companion pieces and to accept or reject the attribution of the two in tandem. There is, however, no documentary evidence linking them before they entered the collection of the National Gallery in 1937 and 1942, respectively. Slight differences in the size of the panels, the compositional arrangement of the figures, and the quality of execution led former National Gallery curator Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. to argue that the paintings were not companion pieces and that the attribution of Girl with a Flute to Vermeer could not be maintained. Accordingly, in 1978 the painting was classified as “Circle of Vermeer.” Wheelock subsequently modified his assessment and stated that “removing the Girl with a Flute from Vermeer’s oeuvre was too extreme given the complex conservation issues surrounding this image.” To account for some of the painting’s curious features, he proposed that Vermeer initially blocked in the painting sometime in the mid-1660s and that another artist revised it at later date. Based on his hypothesis, the painting was cataloged as “attributed to Vermeer.”

Despite its modest appearance, Girl with a Flute has a more complex relationship to Vermeer than Wheelock has proposed. A combination of traditional connoisseurship, understanding of historical painting practice, and the latest results of an array of technical analyses shows that Girl with a Flute was made not by Vermeer, but by someone who, despite understanding that artist’s distinctive working methods, was unable to achieve the same level of finesse: conceivably, an unknown studio associate.

Several factors relate Girl with a Flute to paintings by Vermeer, and specifically to Girl with the Red Hat. The overall conception of the two paintings is undeniably close. Both are tronies: informal, anonymous head studies that offered artists a vehicle for exploring physiognomy, facial expressions, unusual costumes, and striking effects of light and shadow. The depth of both spaces is compressed, with the women posed between a tapestry-covered wall and a chair with lion-head finials. Light coming from each sitter’s left suffuses their left cheeks, noses, and chins with rosy highlights, which are countered by the greenish shadows cast by the broad and striking hats they wear. To understand the reasons for identifying Girl with a Flute as the creation of a close associate of Vermeer and not the artist himself, it is necessary to peer below the surface, where technical examination has yielded results that both link the painting to works by Vermeer (including Girl with the Red Hat) and reveal the differences between them.

Girl with a Flute is indisputably a 17th-century painting. Dendrochronology has determined a felling date for the wood in the early 1650s, and pigments identified throughout the painting are both consistent with 17th-century practice and also characteristic of Vermeer. For example, a paint sample taken from a yellow highlight on the young woman’s left sleeve includes natural ultramarine, lead white, and lead-tin yellow. Lead-tin yellow was prevalent in the 17th century, but not later.

However, at every stage of the painting process, the execution of Girl with a Flute is less assured than that of Girl with the Red Hat or any other painting by Vermeer. Although the panel was traditionally prepared with a double ground layer, this appears to have been inexpertly done, perhaps even by an amateur. Unlike the smooth surfaces observed in the ground layers of Vermeer’s paintings, the upper ground layer here has an unusually coarse and brushmarked texture that would have made it impossible to achieve a refined finish in the completed painting. While Vermeer used the underpaint stage to fluidly model forms and quickly define areas of light and shadow, in Girl with a Flute this underlying layer is clumsily applied, with brushstrokes that make little deliberate attempt to model form.

Poor technique in the painting’s underlayers, presumably the mark of an inexperienced artist, caused paint defects that impacted the surface appearance. These include wide drying cracks in dark areas and wrinkles in white areas that had to be scraped down to level the surface before the final paint was applied . Such severe paint defects are rarely observed in works by Vermeer. These features were interpreted by Wheelock as damages to the underpaint—which he assumed to have been done by Vermeer—that had to be corrected before the final paint could be applied—which he surmised had been done by another, later hand. A simpler and more plausible explanation, however, is that they represent the errors of a painter who had not yet experienced (or chose to ignore) the consequences of improperly preparing their materials. The extensive modifications to the composition visible in x-radiographs and infrared reflectograms may be further evidence of an artist learning as they went and making a determined effort to bring the composition to a satisfactory balance.

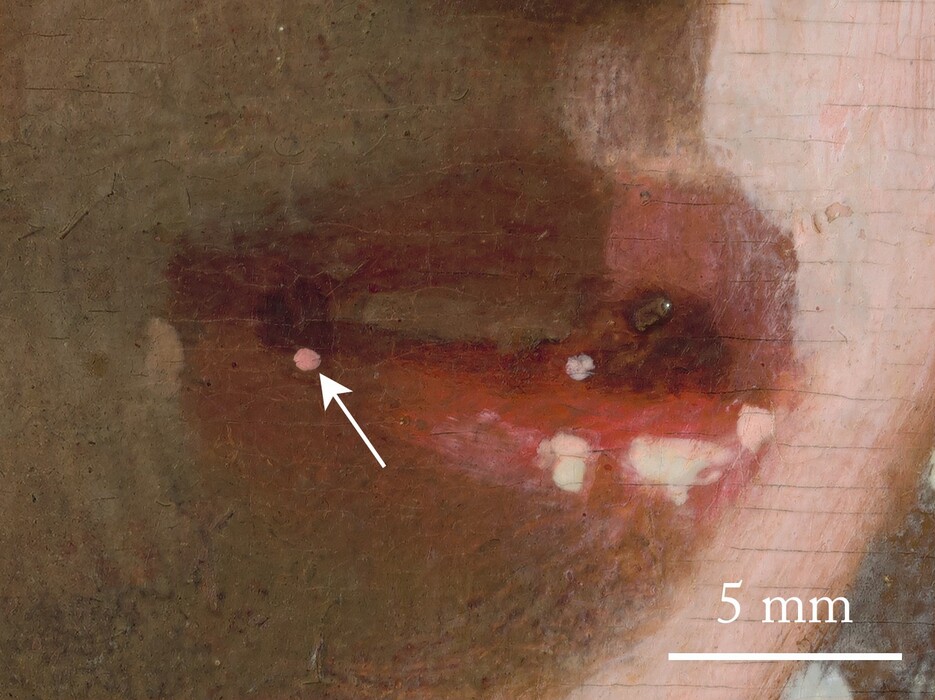

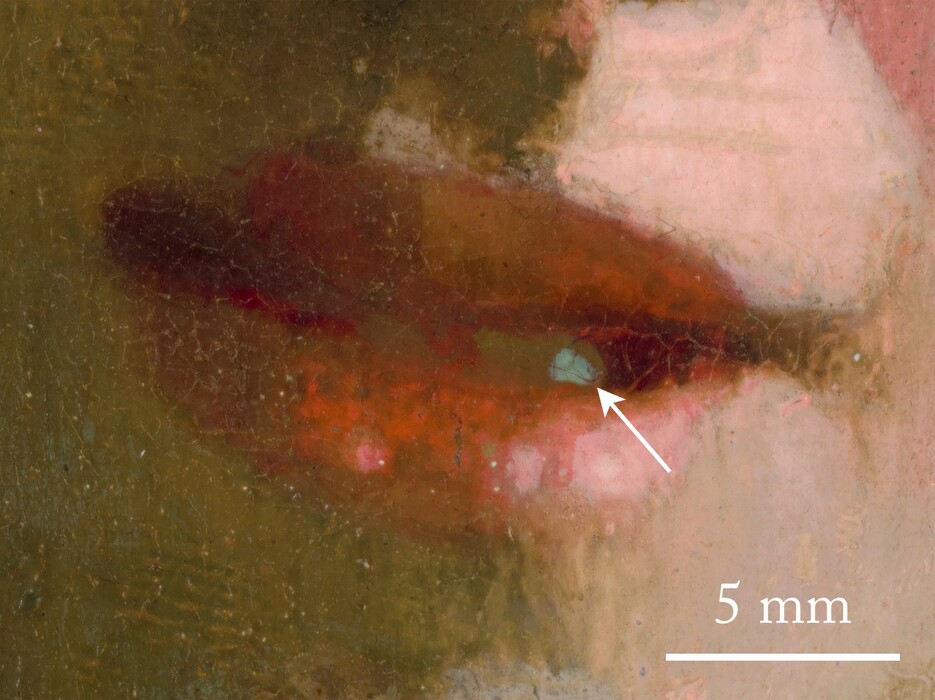

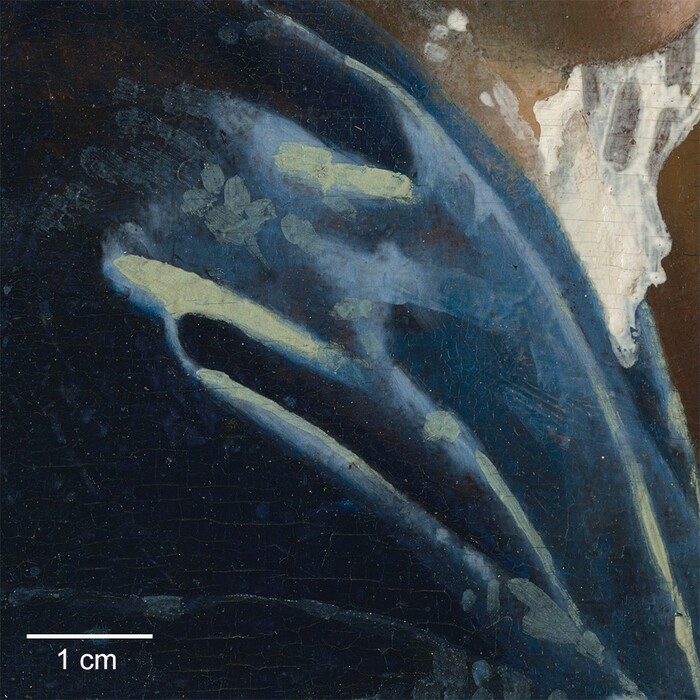

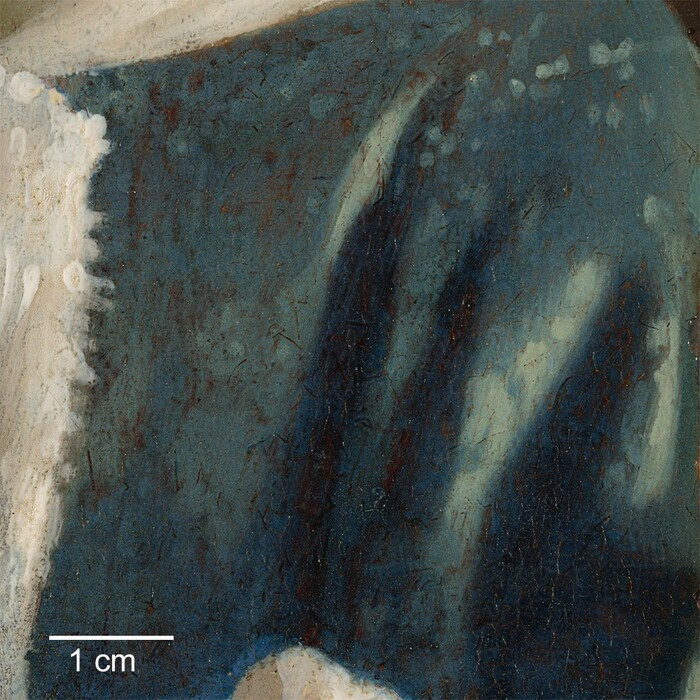

The final paint of Girl with a Flute not only reveals an intimate knowledge of Vermeer’s idiosyncratic painting practice, but also betrays the artist’s struggle in mastering his process and technique. In both Girl with a Flute and Girl with the Red Hat, the dull, greenish shadow cast by the hat over most of the face includes green earth, an unusual pigment choice for flesh tones in Dutch paintings. Although Vermeer used green earth for flesh tone shadows at times throughout his career, the practice is virtually unknown among his contemporaries. In both paintings, this greenish shadow is interrupted on one cheek by broad swaths of bright pink highlights. But while Vermeer modulated flesh tones with delicate strokes of his brush, the painter of Girl with a Flute formed the cheek highlights with hard-edged planes of thick, unvaried pink or gray paint and applied the greenish shadows with a similarly heavy hand , . In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer suggested the moistness of his model’s glistening mouth and eyes with tiny dots of highlight that incorporate the color around them—faint pink at the corner of the mouth and blue green in the eye peering out from greenish shadow. The artist of Girl with a Flute also added dots of highlight but, apparently oblivious to Vermeer’s intentional color harmonies, incongruously placed a blue-green dot within the pink mouth , .

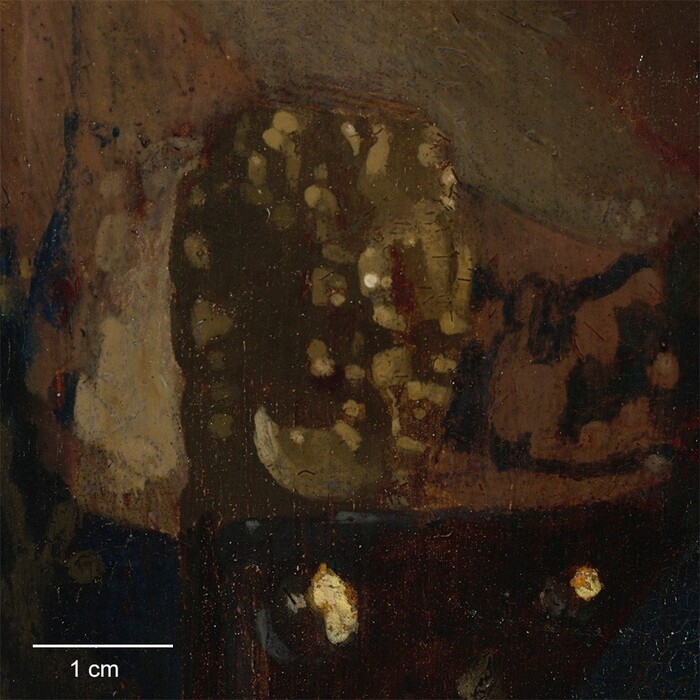

Such qualitative disparities are also evident in the painting of the chair’s lion-head finial, where the artist dutifully followed Vermeer’s process for crafting diffuse highlights to suggest an abstracted play of light. Yet the curves and dashes with which Vermeer magically conjured up the carved head of the chair’s finial in Girl with the Red Hat are, in Girl with a Flute, just meaningless patches of color on a shapeless form —the work of an artist who understood the process but was unable to achieve the effect. In the deepest shadows of the garments in both Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute, brown underlayers glimmer through the thinly applied surface paint, and highlights formed by admixtures of white lead and lead-tin yellow have been touched onto the surface in dots and brushed along the folds in angular strokes. In comparison to the delicately patterned brushstrokes and nuanced palette of warm and cool highlights evidenced in Girl with the Red Hat, the jacket in Girl with a Flute is simply modeled, with randomly dotted highlights and with the white and yellow pigments mixed uniformly throughout , .

The many similarities with Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat and the evident differences in material knowledge and skill of execution suggest that Girl with a Flute represents a student’s or workshop associate’s earnest response to that vibrant and engaging painting, or another similar, now lost painting of its type. There is, however, no record of a studio in which Vermeer trained or was assisted by another artist or artists, and most scholars have deemed such an arrangement unlikely and unnecessary for an artist who probably executed just one or two paintings per year. Vermeer registered no pupils with the Delft painter’s guild, and the brief notes made by visitors to his studio make no mention of assistants. Yet artists did not always formally register their pupils with the guild, and visitors rarely recorded the presence of anyone other than the primary artist. It is entirely possible that Vermeer took on a pupil or apprentice at some point in his career, perhaps welcoming the tuition fees as a source of much-needed income. Alternatively, he may have had help from family members, possibly enlisting his children to assist with routine tasks like grinding pigments and preparing supports. Scholars have periodically floated the notion of Vermeer family members working in his studio, though there is no archival evidence to indicate that any of Vermeer’s 11 children inherited their father’s artistic skills or pursued careers in the arts.

In sum, while the theory that Girl with a Flute was begun by Vermeer and completed by another artist cannot be sustained, it simply is not possible to know who did paint the work or under what circumstances it was painted. It is clearly dependent upon, and probably closely postdates, Girl with the Red Hat. With present knowledge, we cannot be sure whether it was created in honest emulation or with the deliberate intent to fool a discerning 17th-century Dutch art market, as it fooled connoisseurs in the early 20th century.

Technical Summary

The support is a single, vertically grained oak panel with beveled edges on the back. Dendrochronology gives a tree felling date in the early 1650s. A thin, smooth, white chalk ground was applied overall, followed by a coarse-textured gray upper ground. A reddish brown painted sketch exists under most areas of the painting and is incorporated into the design in the tapestry.

Full-bodied paint is applied thinly, forming a rough surface texture in lighter passages. In many areas, particularly in the proper left collar and cuff, a distinctive wrinkling, which disturbs the surface, seems to have been scraped down before the final paint layers were applied. Still-wet paint in the proper right cheek and chin was textured with a fingertip, then glazed translucently. The X-radiograph shows extensive design modifications: the proper left shoulder was lowered and the neck opening moved to the viewer’s left; the collar on this side may have been damaged or scraped down before being reworked in a richer, creamy white. The earring was painted over the second collar. These adjustments preceded the completion of the background tapestry. The proper left sleeve was longer, making the cuff closer to the wrist. Probably at the same time, the fur trim was added to the front of the jacket, covering the lower part of the neck opening. Infrared reflectography at 1.1 to 1.8 microns shows that changes also were made to the shape of the hat and contour of the arm on the figure’s proper right side.

The panel has a slight convex warp, a small check in the top edge at the right, and small gouges, rubs, and splinters on the back from nails and handling. The paint is rather abraded in several areas including the decoration of the hat, the sitter’s proper left arm, and the girl’s necklace. There are a number of small losses and areas of abrasion in the background and there is a large loss in the upper portion of the sitter’s proper right collar. The painting was treated in 1995 to remove discolored varnish and inpainting. It had last been treated in 1933 by Louis de Wild.

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. based on conservation reports by David Bull, Catherine Metzger, and Melissa Katz

April 24, 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.53

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.98