Ten Artworks to Understand Early United States History

The portraitist who popularized the steamship. The failed painter who invented the telegraph. The Black sailor who gave his life to protest British occupation.

The stories behind some works in our collection reveal surprising connections to key events and figures in the early history of the United States.

From the Native peoples lobbying to keep their homelands to immigrants facing challenges in their new home, artists used these works to shape American identity, advocate for change, and reckon with our nation’s stories.

1737: The Walking Treaty forces the Lenape people out of their homeland

The first thing you noticed in American folk artist Edward Hicks’s painting Peaceable Kingdom may have been the lion’s layered haircut or the small child petting a leopard. Hicks made some 60 paintings in which humans and animals coexist, inspired by a story from the Bible’s Book of Isaiah.

But look to the left, and you’ll notice what seems to be a meeting between Native Americans and colonists. The parallel scenes suggest that Hicks is comparing one group to the animals and the other to the humans.

The meeting in the background represents the Treaty of Shackamaxon or Great Treaty. According to legend, Lenape (or Lunaapeew) Chief Tamanend and William Penn, founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, met under an elm tree along the Delaware River. They agreed on how to divide the land, allowing the groups to live peacefully as neighbors.

Whether or not that story is true, shortly after Penn’s death in 1718, his sons executed the Walking Purchase or Walking Treaty of 1737, forcing the Lenape people off their homeland.

1770: The Boston Massacre

While better known for his work as a silversmith, Paul Revere also made engravings, etched prints that could be easily reproduced and distributed. This print depicts the Boston Massacre, a 1770 confrontation between British soldiers and locals who had grown frustrated with the occupation.

The five men whom British soldiers killed that day are listed at the bottom of the print as “unhappy sufferers.” They include Crispus Attucks, a sailor and ropemaker believed to be of Black and Native American descent. Attucks quickly became a martyr and hero, one of the first to die for American independence. In other versions of this print, Attucks is identified with a darker skin tone. Revere and others used the print as propaganda to argue for freedom from British rule.

1790: The Capital moves to Washington

Edward Savage began this portrait of The Washington Family only months after George Washington was inaugurated as the nation’s first president.

George and Martha Washington posed for Savage in New York City, then the country’s capital. But the painting is set at the family’s Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon. We see the Potomac River in the background. A map on the table refers to plans to move the capital to Washington, DC.

The Black man standing to the right may be one of George Washington’s enslaved attendants, Christopher Sheels. He was one of the 317 people the Washingtons enslaved at Mount Vernon.

1819: The US Capitol is reconstructed

Samuel F. B. Morse was a painter before he became famous for inventing the telegraph (and Morse code). The young artist decided that, to be taken seriously, he needed to make a major history painting. His subject: the House of Representatives in the United States Capitol.

Morse worked long days for many months to paint the nearly 11-foot-wide canvas. Much of his painting is imagined. At the time, representatives were heatedly debating legislation like the Slave Trade Act and Missouri Compromise. But Morse shows congressmen, staff, Supreme Court justices, and press reading, resting, or in quiet conversation as the chamber is prepared for an evening session.

Pawnee Chief Petalesharo looks on from the visitors’ gallery at the top right. He was part of a delegation from the Great Plains tribes that met with President James Monroe. Speeches delivered at that meeting include the remark, “We have everything we want—we have plenty of land, if you will keep your people off of it.”

1807: Debut of the Clermont steamship

One invention played a key role in early America’s growth and expansion—the steamboat. And central to its popularity? A painter. Pennsylvania-born portraitist turned inventor Robert Fulton made his name building the first successful submarine, but then shifted his focus to making boats that used English steam engines.

In 1807 he debuted the Clermont, which traveled from New York City to Albany, New York. Steamboats were faster and larger than the flatboats that came before them. They allowed goods to be transported around the country and led to further exploration and settlement.

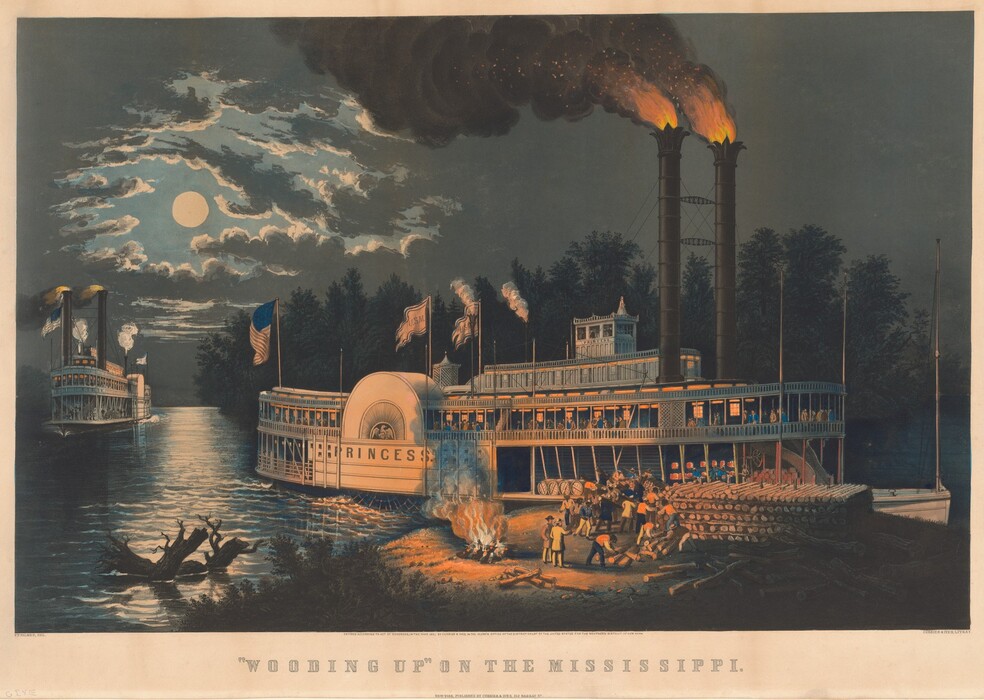

Frances Flora “Fanny” Palmer was a British immigrant known for illustrations of life in the United States. This 1863 print shows the luxurious Princess steamboat stopping for fuel. Black figures, likely enslaved, load lumber onto the boat—a reminder that the exploitation of both people and land drove the Industrial Revolution. White passengers, who enjoyed the boat’s lavish meals and lodgings, stand on the upper deck.

In 1858 the Princess was heading to New Orleans when its four boilers exploded. Dozens of passengers died, and others were seriously injured. It was one of many steamboats to explode or break down.

1850: The Compromise of 1850 establishes California as a free state

Knights on horseback ride off to battle in Jasper Francis Cropsey’s The Spirit of War. Despite its medieval setting, Cropsey’s painting references the military and political battles that were top of mind for Americans in the mid-19th century.

The Mexican American War ended in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe. The United States expanded significantly, taking over all or some of what is now California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas, Wyoming, and Texas. This land brought with it some 115,000 new American citizens. But what kind of country would those new citizens live in?

The Compromise of 1850 allowed California to enter the Union as a free state (one where slavery was banned) and also allowed Utah and New Mexico to decide whether to be free states. It also created a new Fugitive Slave Act that required free states to return escaped enslaved people to their owners and made it illegal to assist runaways.

Cropsey first exhibited The Spirit of War a year later with another painting, The Spirit of Peace. The pair captured the tension between the two sides of the country—and the potential for war.

1855: Castle Garden opens as America’s first immigration processing station

In 1855, nearly four decades before Ellis Island, the country’s first immigrant processing station opened at Castle Garden. Over 8 million immigrants passed through the station in its 35 years. American artist Charles Frederic Ulrich painted this scene of a busy waiting room in 1884. At the center, a mother nursing her baby sits on a trunk with labels that suggest they may be from Sweden.

When this work was exhibited, critics noted the irony of its title—In the Land of Promise. Migrants faced poor living conditions, and the federal government had begun limiting who could immigrate to the United States. Following the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921 set annual quotas for immigrants from each country. Today, quotas still exist for certain immigrant groups.

1858: The Wanderer slave ship arrives to Georgia

Kerry James Marshall’s painting Voyager memorializes some of the last enslaved people brought to America. The name on the boat refers to the Wanderer, one of the last slave ships to come to the United States.

The Wanderer docked at Jekyll Island, Georgia, in 1858, 50 years after the nation had outlawed the transatlantic slave trade. We don’t know exactly how many people had been forced onto the boat before it left from West Africa, but many died on the six-week journey across the Atlantic, known as the Middle Passage. The 409 people who survived were sold into slavery at markets in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida.

Marshall surrounds the figures on the boat with symbols. For example, images of fetuses and a skull reference the tragic deaths of the ship’s captives.

1863: 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment storms Fort Wagner

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial, 1900, patinated plaster, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, Cornish, New Hampshire, X.15233

Just weeks after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the governor of Massachusetts began recruiting Black soldiers. More than 600 men volunteered to serve in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, including two sons of orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. However, Black soldiers were not allowed to be officers. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the son of an abolitionist family, was chosen to lead the regiment.

On July 18, 1863, the regiment led an assault on Confederate forces at Fort Wagner in South Carolina. Nearly half of the Union soldiers, including Shaw, were captured or killed. Their bravery was widely reported and is said to have convinced General Ulysses S. Grant to recruit more Black soldiers. And they inspired many Black men to enlist—more than 180,000 served the United States Forces during the Civil War, fighting for the permanent end to slavery and to restore the Union.

In the 1880s, Shaw’s family commissioned Irish American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to make a monument honoring the 54th. His initial versions focused solely on Shaw. The family asked Saint-Gaudens to include the valiant soldiers that Shaw had served alongside. (While many were still living, Saint-Gaudens did not use any of them as models.) The bronze memorial was unveiled on Boston Common in May 1897. But Saint-Gaudens wasn’t completely satisfied—he kept working on this slightly different plaster version for several more years.

1864: Yosemite Valley established as first federally protected park

Carleton Watkins was one of many adventurers to move out West for the Gold Rush. While living in San Francisco, Watkins learned the art of photography and established a business making photographs for land dispute cases and mining interests.

In summer 1861 Watkins carried his (large) camera to California’s remote Yosemite Valley. His photos of sublime landscapes and magnificent trees were a wonder to viewers around the country.

Watkins’s photographs also proved useful in lobbying efforts to protect the land from development or deforestation. In 1864 President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, providing the land with federal protection. This would eventually lead to the creation of the National Park System.

While national parks would prove essential to preserving and protecting places like Yosemite Valley, they led to the Native Ahwahnechee people (also known as the Southern Sierra Band of Miwok Indians) being pushed out from the region they’d inhabited for thousands of years.

You may also like

Article: Robert Longo’s Huge Drawings of America’s Seats of Power

The American artist challenges our ideas about the medium with some of the largest drawings you’ll ever see.

Article: David Drake’s Poetic Pottery Was Resistance

We know so much more about Dave than we otherwise would because he signed his vessels, and also inscribed them with poems, during a period of harsh anti-literacy laws.