How Herb and Dorothy Vogel Built One of the Greatest Modern Art Collections—and Then Gave It All Away

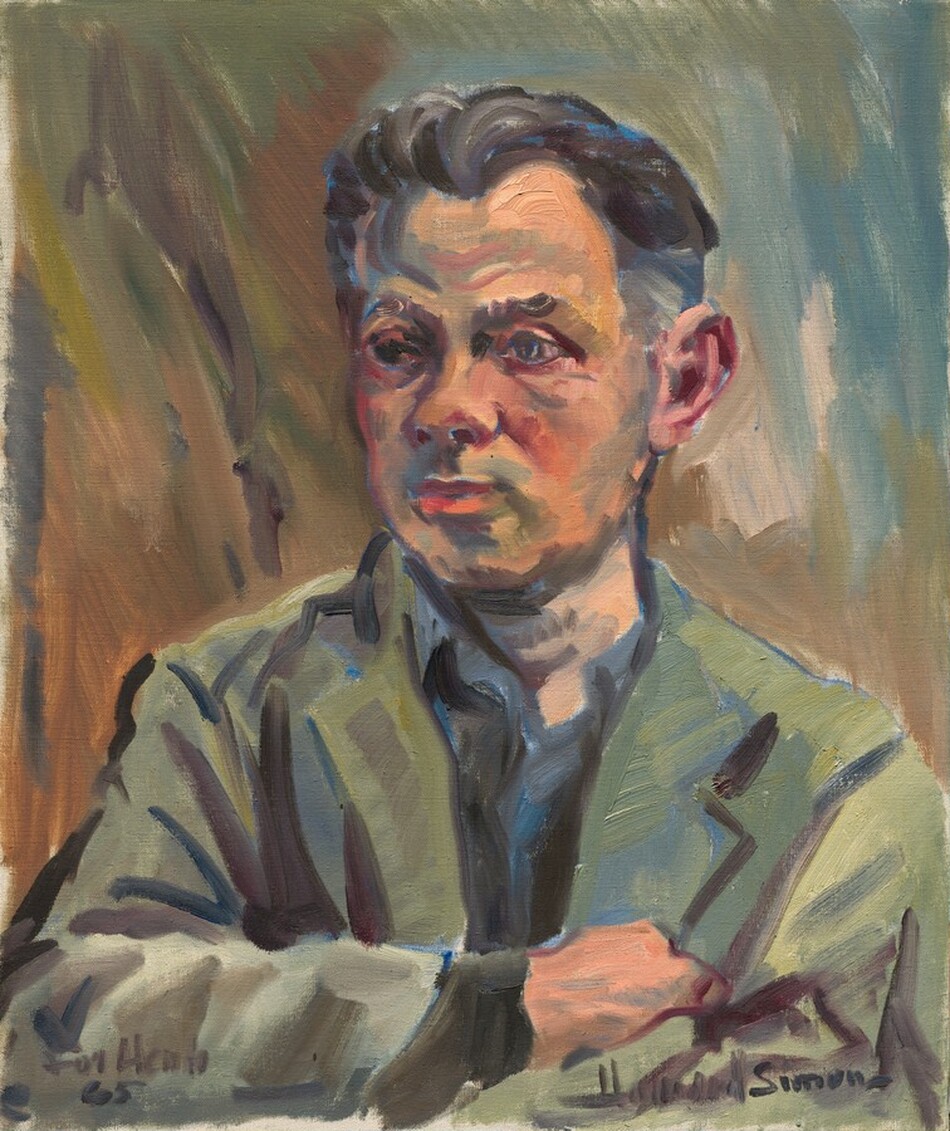

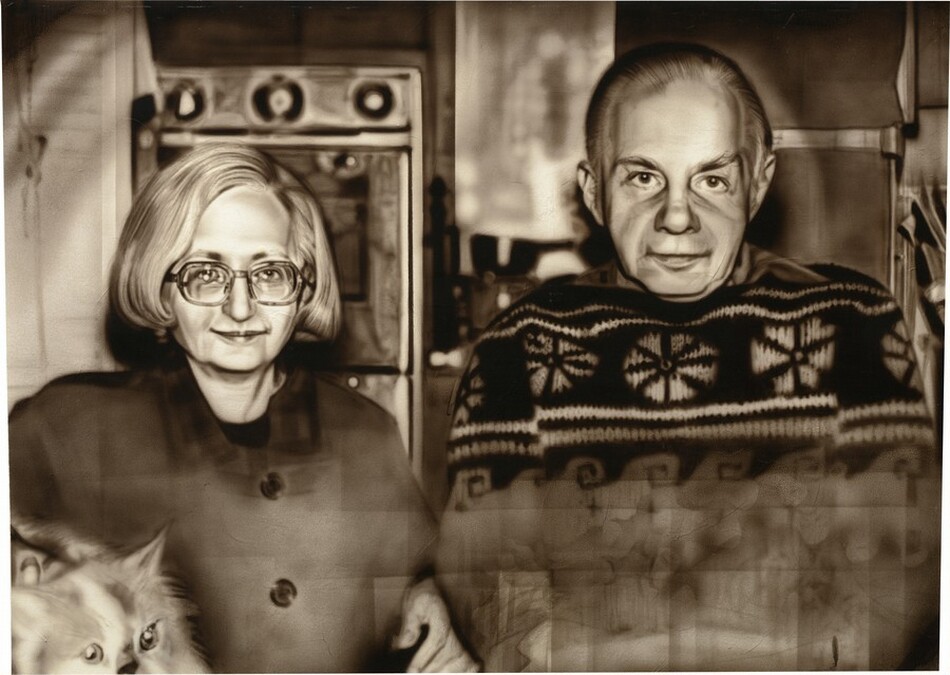

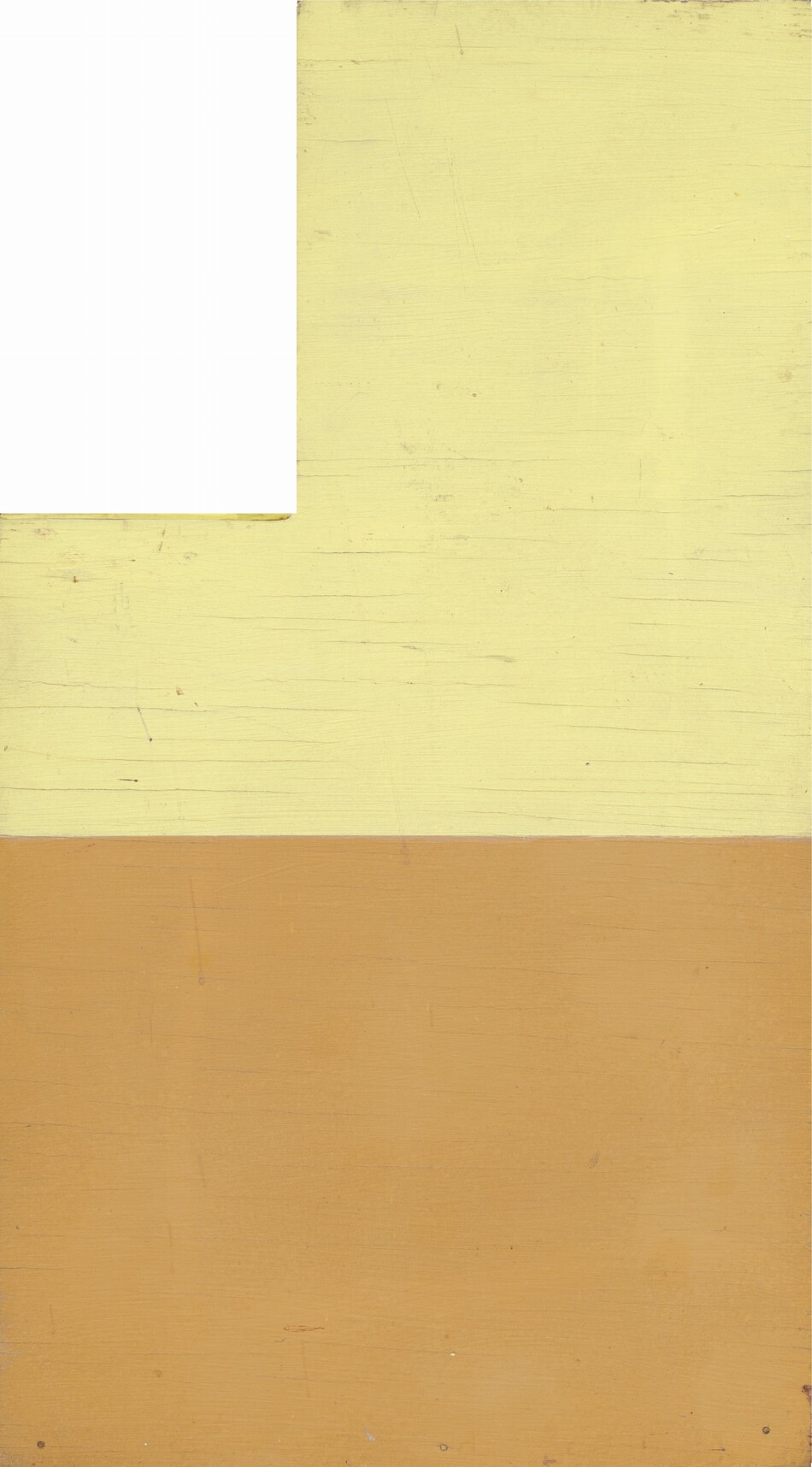

Michael Vinson Clark, Collected Collector (Portrait of Herb), possibly 1983, oil on linen, and Collected Collector II (Portrait of Dorothy), possibly 1983, oil on linen, National Gallery of Art, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection.

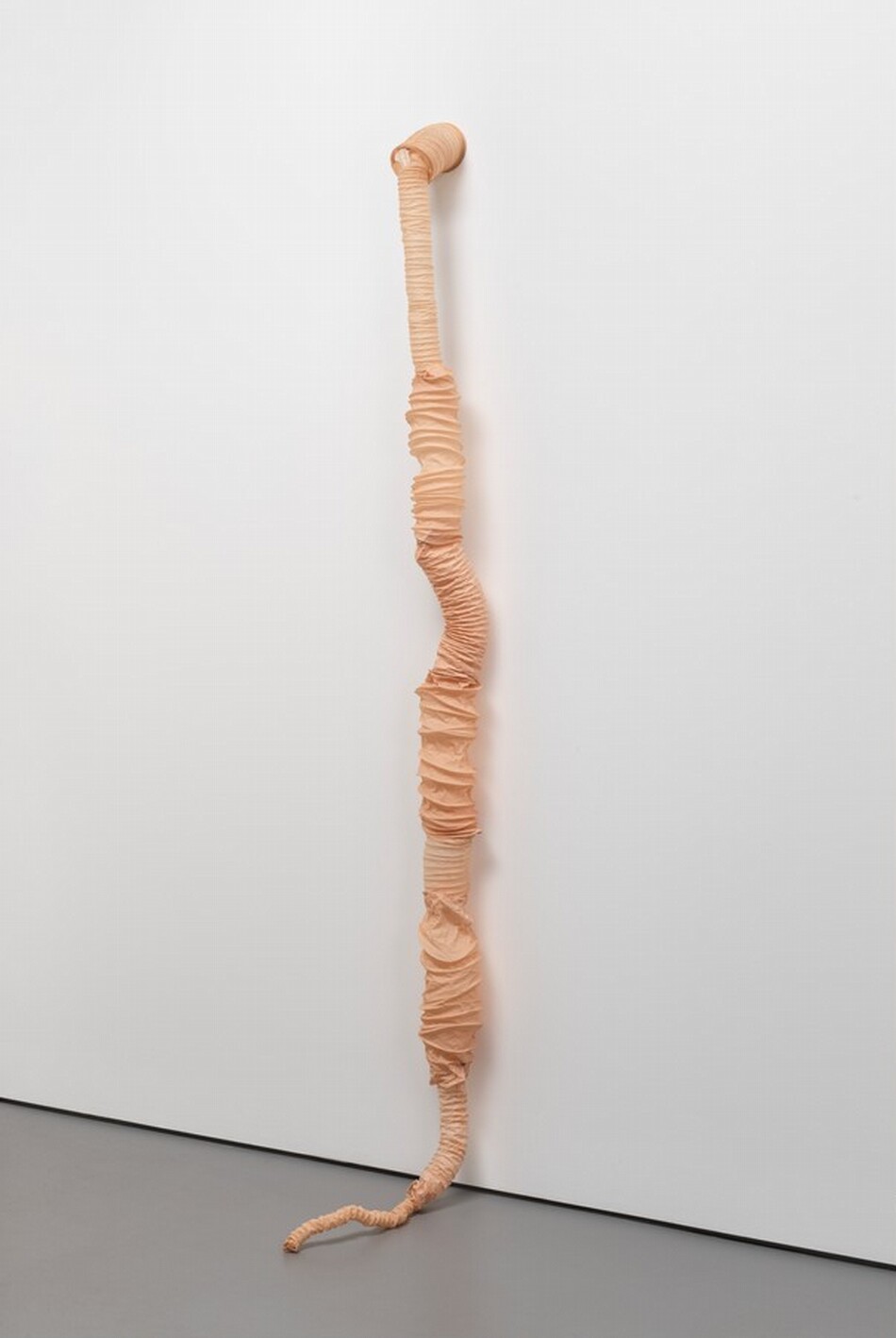

On November 10, 2025, the inimitable art collector Dorothy Vogel passed away. Along with her husband, Herbert Vogel (fondly known as “Herb,” he predeceased her in 2012), she amassed one of the most significant collections of 20th-century American art: over 4,000 works in total, with holdings by conceptual and minimalist artists like Sol LeWitt, Lynda Benglis, and Donald Judd. And what’s more astounding, they did it on their combined librarian and postal clerk salaries. Read on to learn more about this extraordinary couple and the legacy of art they left behind.

The Vogels had modest means.

Unlike most other art collectors, the Vogels weren’t wealthy. They started out as aspiring artists. After they got married in New York in 1962, Herb enrolled at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, and Dorothy joined him in drawing and painting classes to share in his interests. But they soon realized they took much greater joy in looking at others’ art rather than making their own, so they quit their Union Square studio and quickly pivoted to collecting.

To sustain their lifestyle, Dorothy worked as a reference librarian for the Brooklyn Public Library and Herb as a US Postal Service clerk. They lived modestly on Dorothy’s salary and dedicated Herb’s paychecks to buying art.

They championed avant-garde artists.

In the 1970s, when works of pop art and abstract expressionism fetched soaring prices on the art market, the Vogels pursued up-and-coming artists whose works they could afford. They zeroed in on artists whose work held little commercial appeal at the time: those making conceptual and minimalist art.

Herb remembered 1965 as a turning point, when they acquired their first work by conceptual artist Sol LeWitt. Herb explained, “I knew something was new. I didn’t know how good or bad it was, I just knew it hadn’t been done before.” LeWitt introduced the Vogels to his larger circle of artist friends, including Robert Mangold. These artists shaped the collectors’ taste for a movement that had not yet found a market.

They built close relationships with the artists they collected.

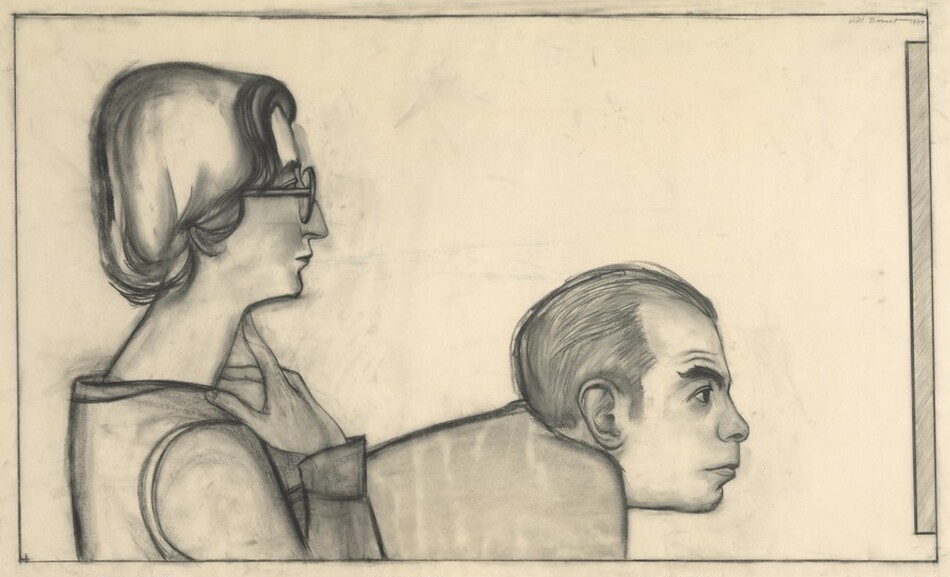

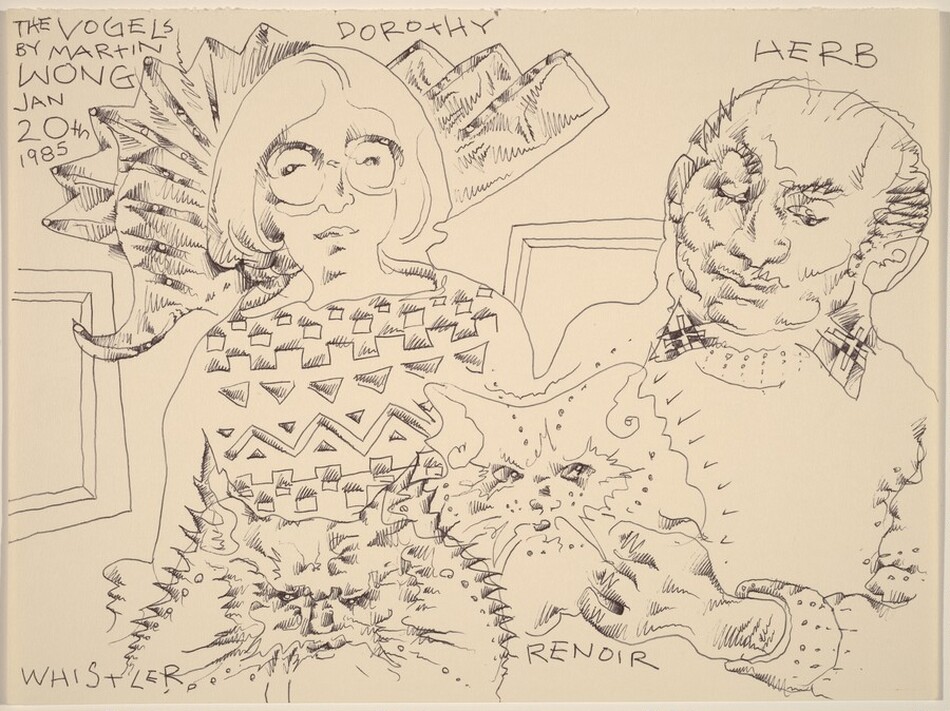

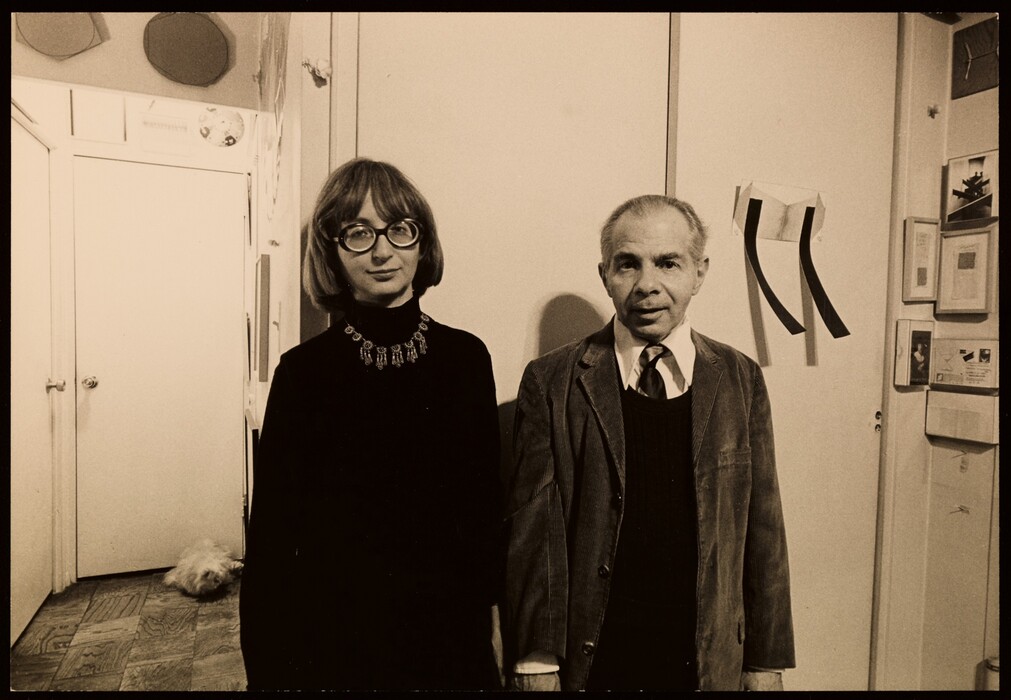

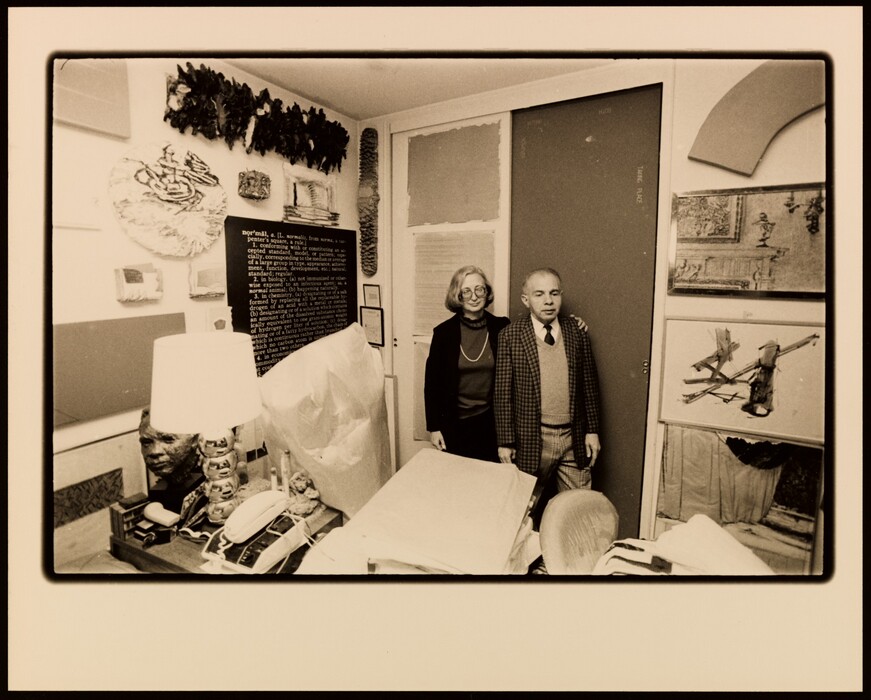

Herb and Dorothy bypassed galleries and art dealers to buy from artists directly. They cultivated close friendships with many artists who were early in their career, seeking to understand the artists’ ideas and working processes and encouraging their exploration. Artist Edda Renouf recalled, “They took their time looking at my works with full attention [which was] very inspiring to me and the beginning of our long-lasting friendship.” The range of portraits of the two, separately and together, testifies to the affection many artists felt for their humble and curious collectors.

Occasionally they exchanged services for art.

When the Vogels lamented they couldn’t afford a drawing by installation artists Jeanne-Claude and Christo, the artists proposed a different arrangement. They needed to spend the summer in Colorado to oversee their monumental installation Valley Curtain. Would the Vogels take care of their cat Gladys in exchange for the collage? Gladys joined the Vogels’ own eight cats for the summer, and the drawing went home with them as well.

They stored their entire collection in their apartment.

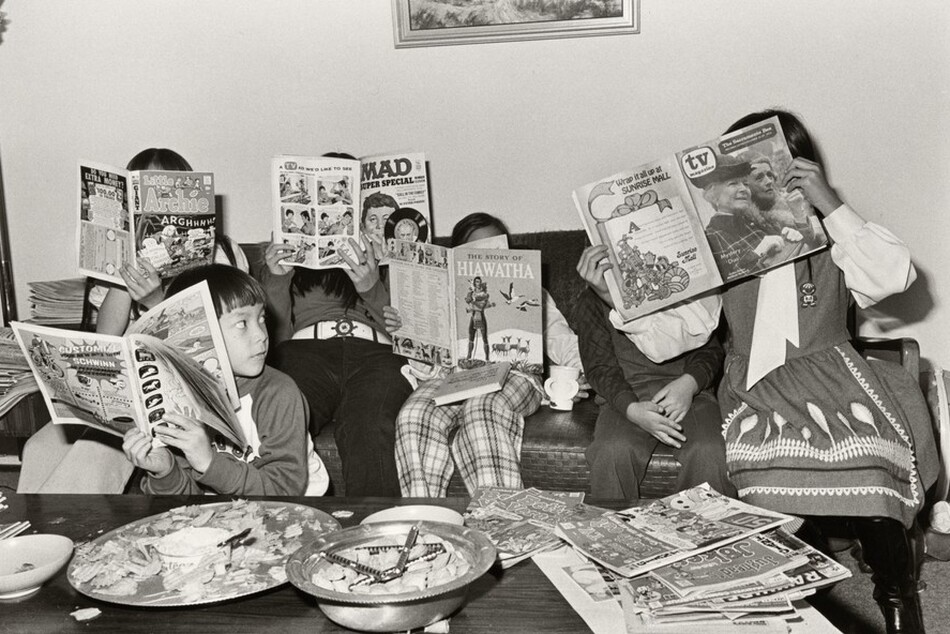

The Vogels were omnivorous collectors. The only restrictions they set on their purchases were that they had to be able to afford the artwork, carry it home via taxi or subway, and fit it within their 450-square-foot, one-bedroom Manhattan apartment.

At the peak of the Vogels’ collecting, over 4,000 works were crammed into their small home. Every wall was covered in paintings and drawings, sculptures were suspended from ceilings and resting on every surface, and the rest were wrapped and stored in crates and boxes. A Carl Andre piece composed of copper tiles was stored in a chocolate box. “Not even a toothpick could be squeezed into the apartment,” Dorothy recalled.

They chose to give their works to the National Gallery of Art.

In 1992, five moving trucks arrived at their New York apartment to transport 1,100 paintings, drawings, photographs, and other objects to Washington, DC. While many institutions expressed interest in their formidable collection, the Vogels chose the National Gallery to be its new home. The museum is free to the public, allowing people from all walks of life to see their collection. The National Gallery also has a policy against deaccessioning (selling off) works in the collection. It matched the Vogels’ commitment to never sell any of their art for profit, even though many artworks they bought inexpensively eventually became worth a fortune. As Dorothy put it, “How do you put a price on something, or someone, that is close to you?"

Sentimental value may have played a role as well. The National Gallery was the first place Herb had taken Dorothy on their honeymoon, and where she received her first art history lesson.

These works from the Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection are currently on view:

Their legacy reached every state of the nation.

The Vogels’ generosity extended far beyond Washington, DC. In 2008, in partnership with the National Gallery of Art, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, they launched the “Fifty Works for Fifty States” initiative, donating 2,500 works to 50 museums across the country—one in each state. The Vogels hoped their national program would allow museums to exhibit work by contemporary artists they otherwise might not have been able to acquire.

Above all, Dorothy and Herb Vogel made clear that their shared devotion to art was not about stockpiling possessions. It was about looking closely at art to find something daring and new, uplifting the artists who light the way, and helping the rest of us see it too.

You may also like

Article: 12 Documentary Photographers Who Changed the Way We See the World

Photographers of the 1970s revolutionized the medium through innovations of both style and subject.

Article: Your Tour of Latinx Artists at the National Gallery

Use our guide to explore works by Latinx artists on view in our galleries.