Smithsonian Scientists on How Artists Depicted Five Curious Creatures

Jan van Kessel, Study of Insects and Reptiles [center], c. 1660, oil on copper, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA

When did you first see the pattern of a dragonfly’s wing? Or learn that giant mammals roam the ocean? If you had lived in Europe in the 16th or 17th centuries, your first exposure to the wonders of the natural world may have been through art. Artists of the period helped share newfound knowledge of insects, animals, and other beestjes or “little beasts.”

Our exhibition Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World pairs paintings, prints, and drawings from our collection with specimens and taxidermy from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Specialists from the museum helped us identify some magnificent (or mysterious) animals. Find out how artists represented, or sometimes misrepresented, the creatures in their works.

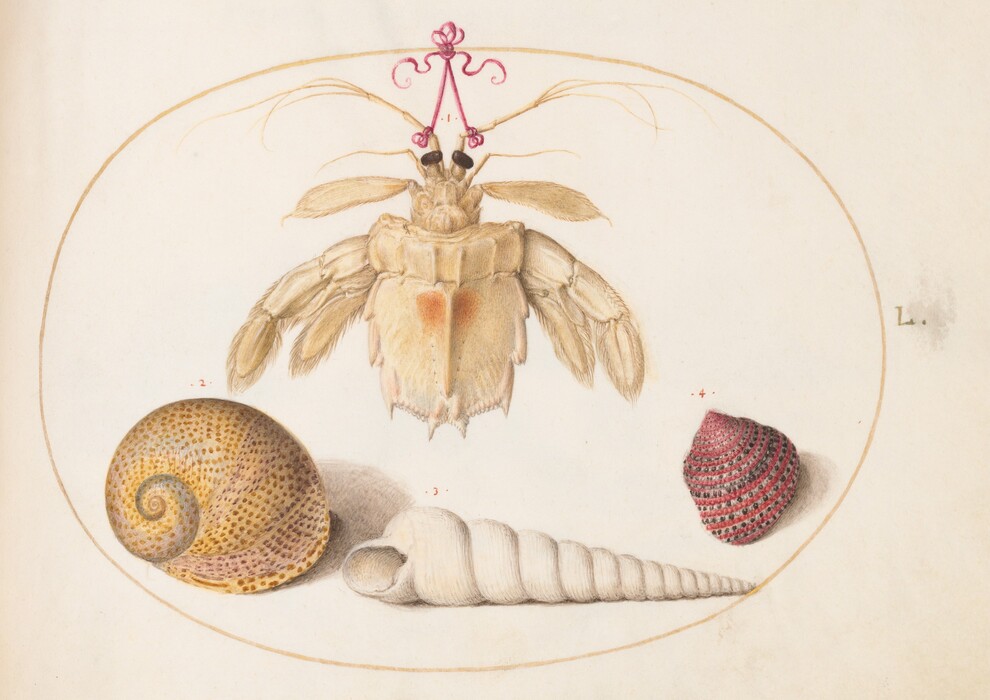

1. Joris Hoefnagel’s Punchy Mantis Shrimp

A crustacean dangles from a ribbon tied to the border of this page. Art historians were stumped by what creature Joris Hoefnagel was trying to represent here, in the Aqua volume of his The Four Elements.

That is until William Moser, collections manager for invertebrate zoology at the Museum of Natural History, solved the mystery. . . at least partially. The suspended creature has the head and tail of one of the heavyweights of the sea—the mantis shrimp.

But Hoefnagel’s mantis shrimp is missing its most important feature—its front claws. Though only 6–12 inches long, these shrimp use their claws to strike with such speed that they boil the water around them. Their punches produce vapor-filled bubbles that collapse, creating a shock wave that can stun or kill prey, even if their strikes miss.

Why did Hoefnagel omit the shrimp’s standout feature? He may have been working from a broken specimen that was missing its abdomen and claws. More likely though, the artist was playing a game with the viewer, challenging their knowledge of the natural world.

Joris Hoefnagel’s partial mantis shrimp lived on beyond this drawing. His son Jacob Hoefnagel included it in an engraving as part of the series, Archetypes and Studies. The earliest printed images of dozens of species, these relatively cheap prints became accessible to a wide public.

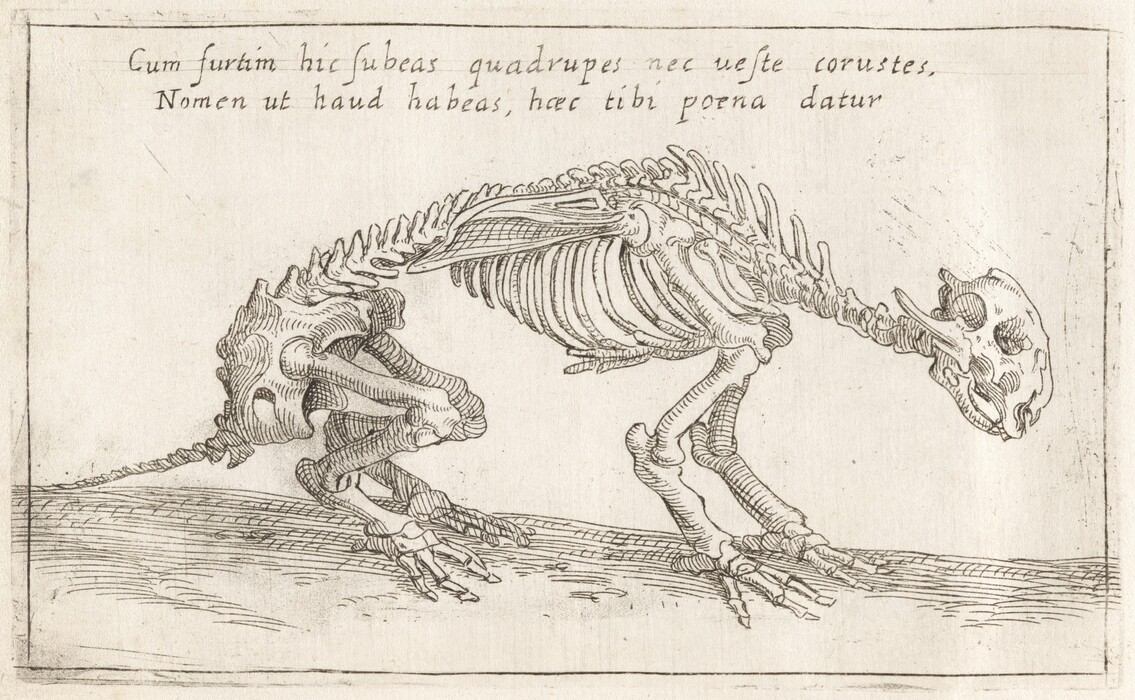

2. Teodoro Filippo di Liagno’s Sneaky Four-Legged Creature

This print comes from a set of etchings that depict real animal skeletons owned by the artist’s friend, Johann Faber. Faber likely commissioned the prints for fellow members of the Academy of the Lynx-Eyed, a Roman society dedicated to the study of natural sciences.

Each print includes the animal’s Italian name and a Latin verse that describes the creature and its behavior. But Liagno didn’t name this quadruped, and the description is cryptic:

When you wish to sneak around here on all fours brandishing no clothes,

So that you have no name, I give you this punishment.

Liagno blames the animal for “sneaking around” without “clothes” (skin). But whose fault is it that he couldn’t identify the creature? The skeleton’s, the scientist’s, or the artist’s?

Mammal specialists at the Museum of Natural History thought this most closely resembled an Old World porcupine skeleton—but not exactly. Compare the legs, pelvic regions, and scapulae (shoulder blades) of the two. Notice the differences?

We don’t know what accounts for the differences. Maybe the drawing Liagno copied had errors. Or perhaps the skeleton he worked from was missing pieces or was also unidentified.

3. Jan van Kessel’s Peanut-Headed Lanternfly (and its Imaginary Neighbor)

Jan van Kessel, Study of Insects and Reptiles [center], c. 1660, oil on copper, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA

Artist Jan van Kessel the Elder arranged the little beasts in this painting by their visual appeal. Shown all the same size—moths as big as lizards—they seem to float in space.

This work was a central panel in an “art cabinet” that would have held a collector’s small objects of “curiosity.” And indeed, Van Kessel includes species from the Americas that European viewers would have considered oddities. The peanut-headed lanternfly, for example, is native to South and Central America. As the insect’s name suggests, its head is shaped like a peanut. And false eyes on the sides of their unusual heads make the lanternflies look more like lizards or snakes to predators.

But some of the fantastical critters Van Kessel painted are just that. Next to the lanternfly is a creature that looks to be part dragon, part locust. This animal didn’t exist, but it also wasn’t the artist’s invention. It appears in many works from the late 1500s and 1600s. The hybrid may date back to the 1542 plague, when someone claimed to see the Latin words ira dei (wrath of God) on a locust’s wings. After that, locusts were associated with demonic forces and plagues. Woodcuts often showed them with webbed feet, wings, long tails, and antennae extending forward from their faces.

4. Jacopo Ligozzi’s Well-Fed Woodchuck

Jacopo Ligozzi made detailed watercolor studies of animals for the powerful Medici family in Florence. Notice how he captured the animal’s soft fur. Tiny little strokes distinguish each strand of hair and create the feel of a fuzzy pelt.

The woodchuck’s body, on the other hand, is inaccurately round. Ligozzi probably had to work from a skin or a poorly executed piece of taxidermy, rather than from a live animal. Compare his watercolor to this specimen from the Museum of Natural History. What other differences do you notice?

5. Jan van Kessel’s Chatty Parrot

This study from the circle of Jan van Kessel the Elder features a menagerie of birds. Resting on a branch in the middle is a hefty parrot that specialists at the Museum of Natural History identified as a yellow-headed amazon.

Like today, parrots were popular pets in the 1600s, though only the very wealthiest could afford them. The yellow-headed amazon, renowned for being an excellent talker, is now endangered because of poaching for the international pet trade.

Yellow-headed Amazon parrot at Cougar Mountain Zoological Park. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Exhibition : Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World

Experience the wonder of nature through the eyes of artists. Look closely at art depicting insects and other animals alongside real specimens.

You may also like

Article: Exquisite Corpse with Kerry James Marshall (and friends!)

The history painter takes inspiration from an old surrealist game — and so can we, as an opportunity for connection.

Article: Drawing with Scissors with Romare Bearden

Wendy MacNaughton takes us on a journey to meet the legendary Harlem artist known for his collages — and reflect on our own homes and families.