What Did We Eat Before Colonization? A Native Chef and Artist Connect Over Plant Knowledge

Food is a basic human need. In our Food for Thought series, James Beard Award–winning journalist, scholar, and writer Cynthia Greenlee hosts a gathering of historians, food journalists, poets, chefs, and farmers and invites them to riff on food-related works of art in our permanent collection.

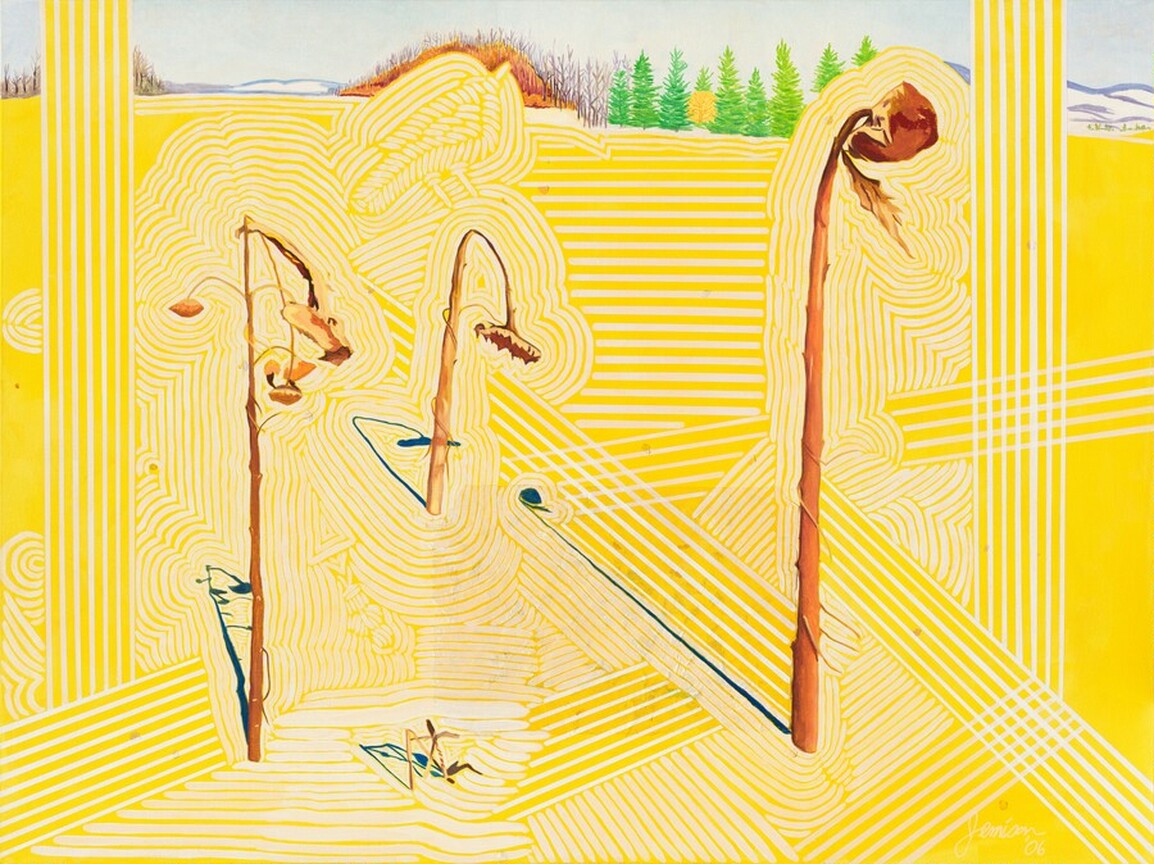

The artist behind Sentinels is G. Peter Jemison (Seneca Nation of Indians, Heron Clan), but I know him as “Pete.” A tall, quiet man with gentle eyes that belie the strength of his character. In the many years that I have known him, I’ve never heard a raised voice. A deeply spiritual man. He listens to conversations intently, almost excitedly. One can see his great curiosity for everyone and everything around him.

Pete is the founding site manager of Ganondagan, the location of a thriving 17th-century Seneca village. (He recently retired to focus on his art, but still lives nearby in upstate New York.) Haudenosaunee white corn was grown in abundance at Ganondagan. Whether on its interpreted trails, in the Seneca Bark Longhouse, or in the Seneca Art & Culture Center, you can sense the presence of those who have gone before and the wisdom harbored in the land.

Pete and his wife Jeanette (Mohawk, Snipe Clan) now steward the Ganondagan White Corn Project. Scholar John Mohawk (Seneca) and his wife Yvonne Dion Buffalo (Samson Cree) founded the project, which aims to bring white corn back as a staple of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) diet. When they walked on, Pete and Jeanette took over.

I have been blessed with the honor of spending time and cooking with John and Yvonne. And Pete and Jeanette have always welcomed me into their home and family. When I was invited to Ganondagan to create food events, we all worked in the kitchens together, laughing and talking. I remember great conversations at the kitchen table and family dinners—and during walks through the woods.

Finding Wild Ginger

I am a chef, so my conversations often meander to the topic of food. I am always seeking and learning more about what was here before colonization. What did we eat? Where did we find it? On one particular day, walking the trails and, of course, talking food, Pete spies a small plant. “What is this?” I say. Pete answers, “Wild ginger.”

I was more than excited. I love ginger. And while researching the many flavors we’ve become accustomed to from the old world, I’d always been sure that we had something similar of our own. And here it was!

Wild ginger (Asarum canadense L.) is a small, low-growing plant with round leaves much like a nasturtium. The root tastes like/is ginger! It grows in the eastern areas of North America and has been used as a medicinal as well as a food plant. Many of our indigenous plant foods are both medicinal and nourishing. This is a knowledge that is passed down through the generations, from one person to another. Precious gifts that must not be forgotten.

This small gift of wild ginger, from Pete to myself, has been significant in my work as a Native American chef. I, too, am obligated to pass on this knowledge.

Chef Loretta Barett Oden discussing sunchokes and summer squash at Slow Food USA in Denver in 2017. Image courtesy of the author.

Sunchokes Through the Generations

Sentinels also has a rich native history. Food! The sunflowers not only grace us with their beauty but they are also the source of nourishment. Their seeds are packed with intense nutrients like vitamin E and selenium as well as beneficial oils.

The peoples of North America have also harvested the roots of certain varieties of sunflowers for millennia. the Europeans referred to them as “Jerusalem artichokes.” (Check out that story.). We name them sunchokes. They can be eaten raw as well as cooked, and this is yet another source of nutrition knowledge handed down through the generations.

So in this work Pete captures the beauty of his subject and surrounds it with the symbolism of his culture, adding deep meaning and intention to his work.

I stand in awe.

If the Sentinels Could Speak

At first glance: sad, the end of summer. The warmth of summer gone. I hang my head in sadness, the cold snow. But on second glance, no. . .

I was once young and strong, firmly rooted in the rich warmth of Mother Earth. My broad leaves like arms stretching out to receive the nourishment of the sun, the rain—growing taller and taller. The bud that would become my crowning glory growing and ready to burst into the glorious beauty of my face, surrounded by the brilliance of my golden petals. . . beckoning, smiling, entreating the busy pollinators to come hither, partake of my nectar, stroll a while, spread your pollen.

I am tall, I am strong, I am oh so beautiful. I am the penultimate sun worshipper. I am the symbol of summer, and I possess a magical power. I can entertain and feed my friends—the buzzy bees, hummingbirds and fluttering butterflies—as they happily stroll and hover. My head held high, turning to watch the sun track across the summer sky.

As the days grow shorter, my head grows heavy with the weight of the next generation. The birds come to feast on my ripening seeds. A few fall to the ground with each visit. The squirrels scamper to gather some of them, but there are many left. I am nothing, if not prolific in my role as Mother. There will be enough to ensure the next family of golden sentinels.

The wind is brisk, and I grow weary. The snow comes to cloak my little ones and bring nourishment to them with the spring melt. I shall stay right here, looking down, guarding them through the winter’s rest. I am their sentinel. When I know they are safe, I shall step aside as they awake, seeking the brilliant sun that helps them grow straight and tall, their beautiful golden faces signaling another season.

You may also like

Article: An Expert Baker’s Take on “Cakes” by Wayne Thiebaud

The painting inspires baker and author Cheryl Day to recall the dessert’s place in her life—and in her family’s history.

Article: Making Pictures of the Animals We Eat

When Dutch artist Willem van Aelst painted dead animals, did he use the images to grapple with the full circle of life?