Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

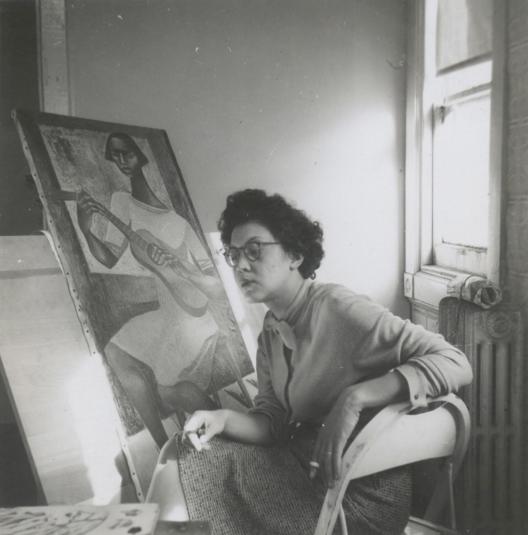

Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett in Her Studio, 1942, Courtesy of The Charles White Archives.

Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett in Her Studio, 1942, Courtesy of The Charles White Archives.

Elizabeth Catlett was an extraordinary artist and lifelong activist who believed in the power of art to promote social change. She created works celebrating human dignity and freedom, depicting with fierce pride her communities: those of Black America and of her adopted country, Mexico. And Catlett was committed to ensuring that her sculptures and prints lived among the people she championed. Experience Catlett’s artistic journey in our exhibition Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist, on view through July 6.

1. She was born and educated in Washington, DC.

Elizabeth Catlett (left) along with her siblings. Addison Scurlock, Catlett Children, John, Cera, and Elizabeth, 1921, Courtesy Elizabeth Catlett Papers, Amistad Research Center, New Orleans, LA

Born in 1915, Catlett navigated segregated DC from an early age. Her maternal and paternal grandparents had been born enslaved, and their stories shaped how she saw the world. As a teen she joined demonstrations on the steps of the US Supreme Court to protest the lynchings of Black Americans across the country.

Despite excelling in her college entrance exams, she was denied admission to Carnegie Mellon University due to her race. Instead, Catlett stayed in DC and enrolled in Howard University’s art program, where she studied under luminaries such as Loïs Mailou Jones and James Porter.

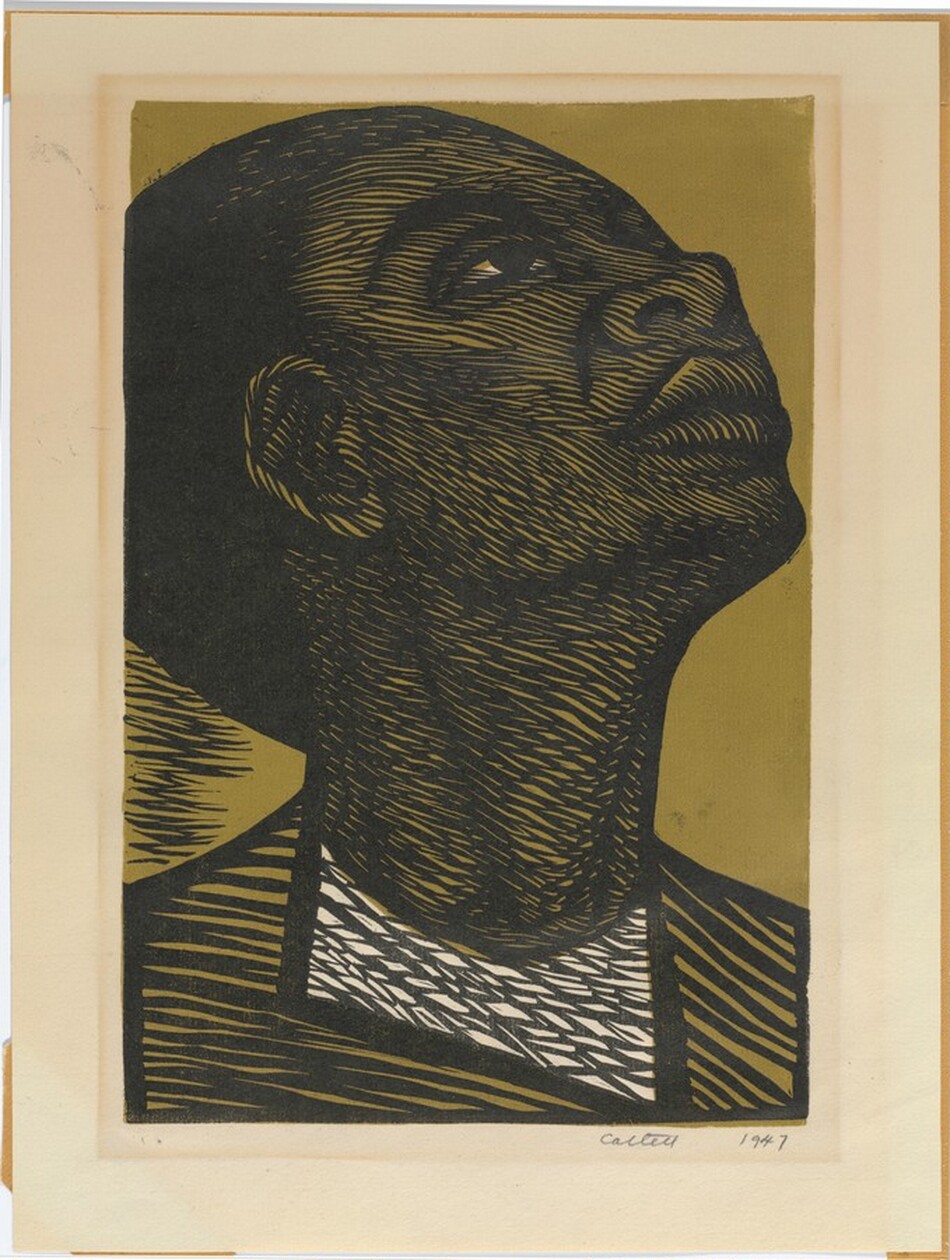

2. Printmaking was central to her art and politics.

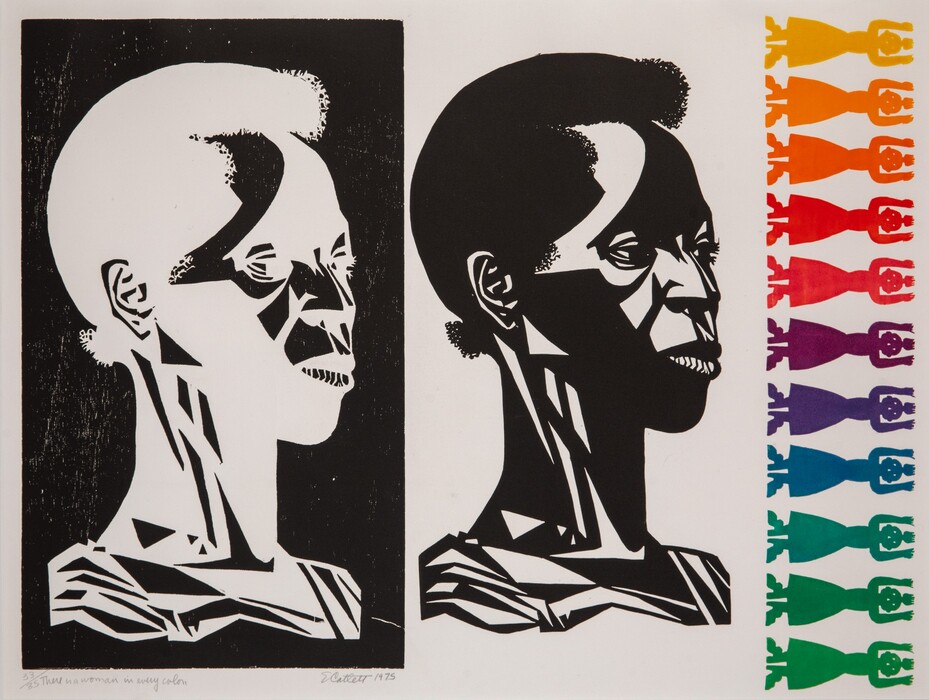

Elizabeth Catlett, There is A Woman In Every Color, 1975, woodcut/linocut, From the Hampton University Museum Collection, Hampton, VA. © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N

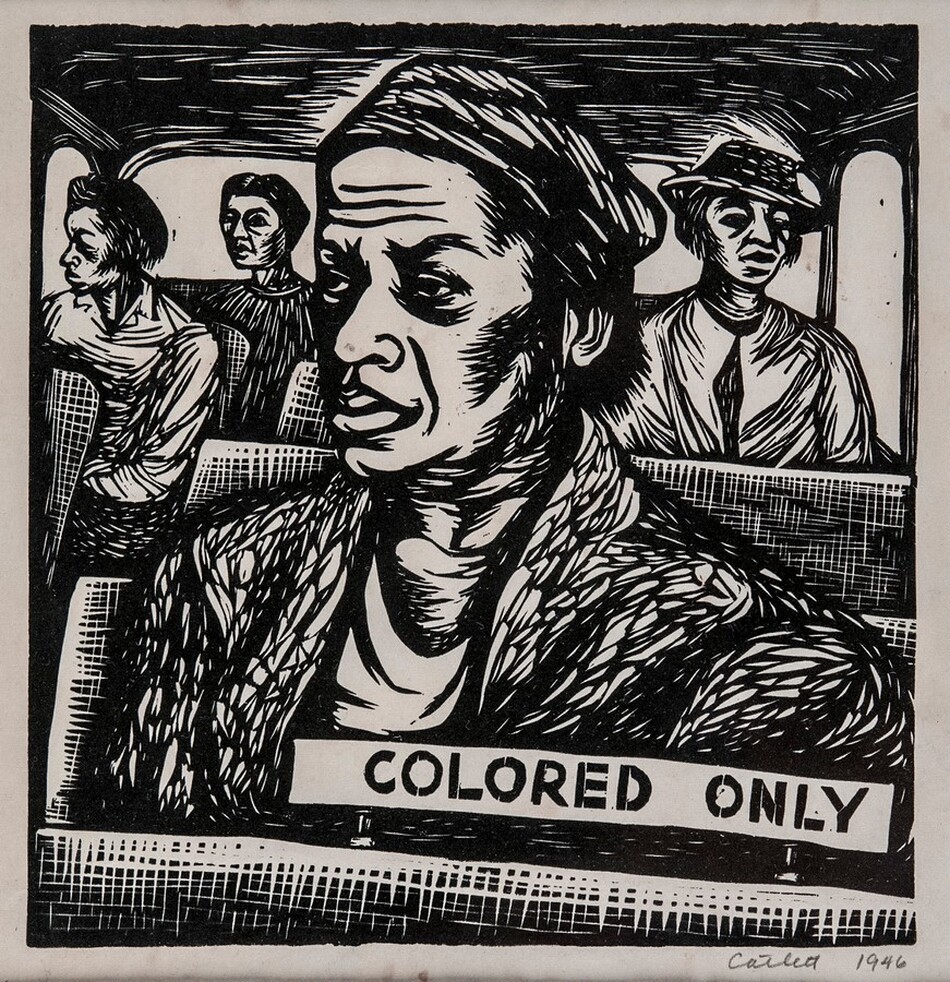

“I am Black, a woman, a sculptor, and a printmaker,” Catlett declared. Catlett believed that art belonged not just to elites but to everyday people. Printmaking allowed Catlett to distribute her powerful images widely, celebrating Black womanhood, labor dignity, and justice. Her prints were accessible in the community centers, schools, and homes of the people whose lives and struggles she so memorably portrayed. Printmaking also furthered Catlett’s artistic practice; its iterative processes allowed her to experiment and repeat motifs throughout her work.

3. Grant Wood advised her to make art about what she knew.

Portrait of Catlett at University of Iowa Graduation. Photographs, Box 4, Addendum II, Amistad Center

Catlett pursued her master of fine arts degree at the University of Iowa, where she studied with artist Grant Wood. She learned from Wood his disciplined and meticulous approach to art making, which she would carry throughout her career. Even as Catlett shifted her studies from painting to sculpture, Wood remained a significant mentor. He encouraged her to take as her subject “something you know the most about.” For Wood, this meant corn fields and red barns. For Catlett, it meant strong and proud Black women, who surrounded her in life but were nearly absent in art.

4. She defied segregation.

The Delgado Museum (now the New Orleans Museum of Art), probably 1950s. Photo via Wikimedia Commons (Family collection of Infrogmation of New Orleans). CC BY-SA 4.0

From 1940 to 1942, Catlett chaired the art department of Dillard University, an HBCU in New Orleans. She was determined to take her students to see a Pablo Picasso exhibition at the Isaac Delgado Museum (now the New Orleans Museum of Art) – but the museum was at the center of a then-segregated city park. Undeterred, she worked with the museum to visit on a day when it was closed to the public. Then she transported her class to its front steps by bus. For many of her students, this was their first time in an art museum.

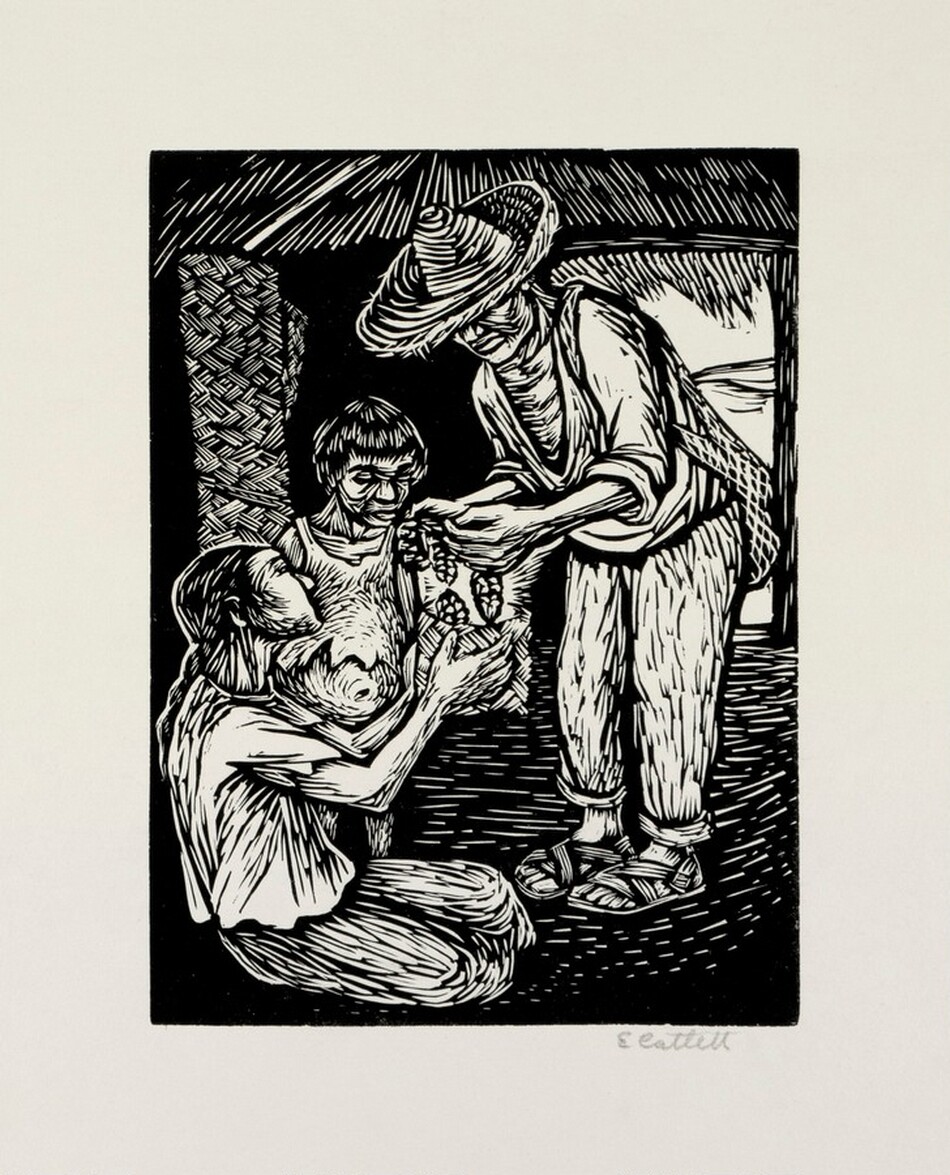

5. She made Mexico her home.

Elizabeth Catlett and Francisco Mora. Courtesy of Dalila Scruggs.

Catlett first became interested in Mexican art when she studied Mexican muralists in college and saw how their works brought art to the people. She came to Mexico in 1946 on a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship and joined the renowned Taller de Gráfica Popular (Peoples Graphic Workshop, or TGP) printmaking collective. TGP members believed in the power of art to educate and promote social change. One of its founders, Raúl Anguiano, introduced Catlett to the TGP’s method of working in series. At the TGP, she mastered linocuts —an economical printmaking process in which compositions are carved into inexpensive sheets of linoleum.

Catlett flourished in Mexico and decided to stay there after meeting and marrying Mexican painter Francisco Mora in 1947. She broke barriers as the first woman to teach sculpture at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, eventually heading the department. There, she developed her distinctive style, drawing upon modern, African, and Mesoamerican visual influences.

6. The Black Woman series is one of her most iconic works.

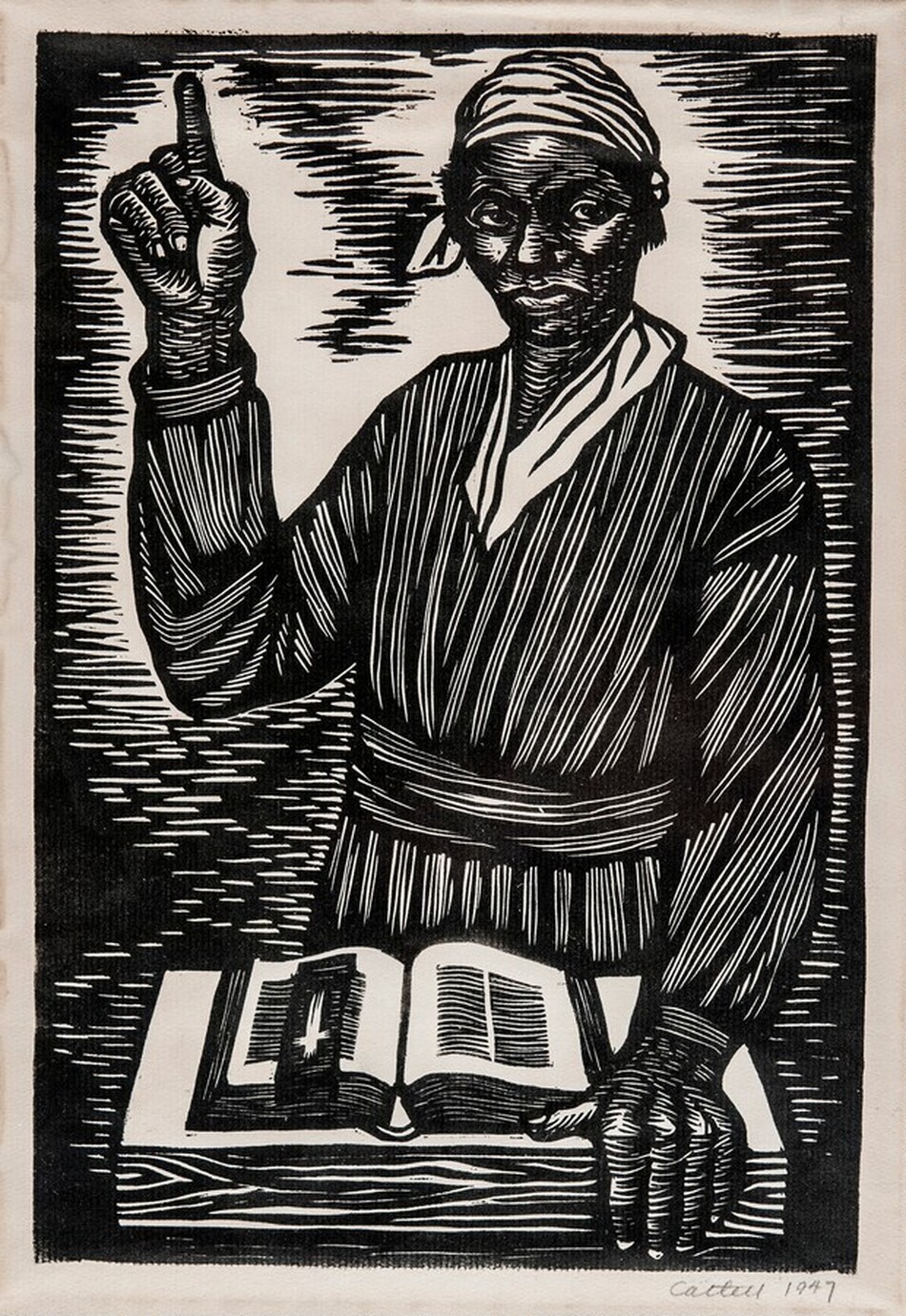

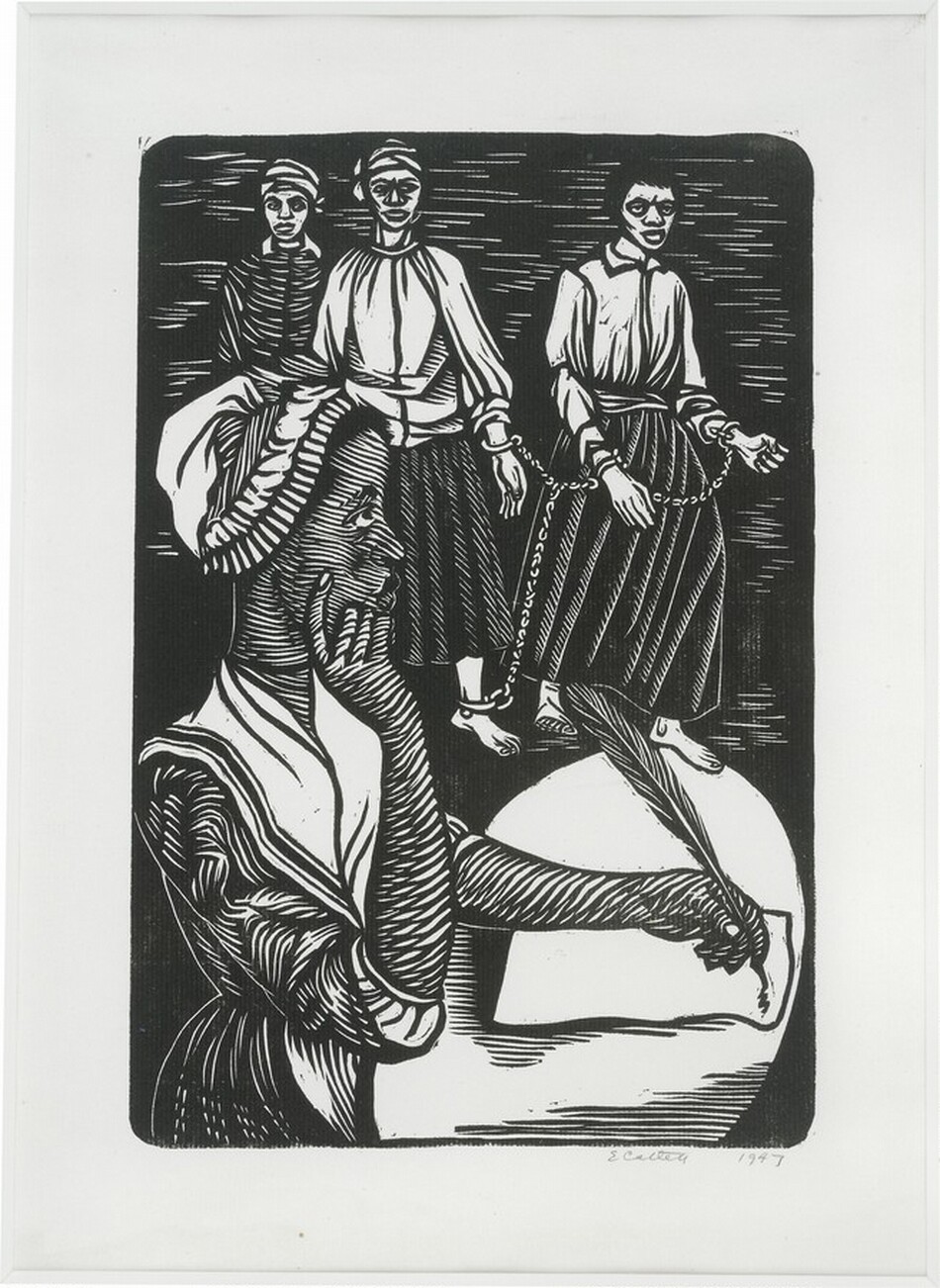

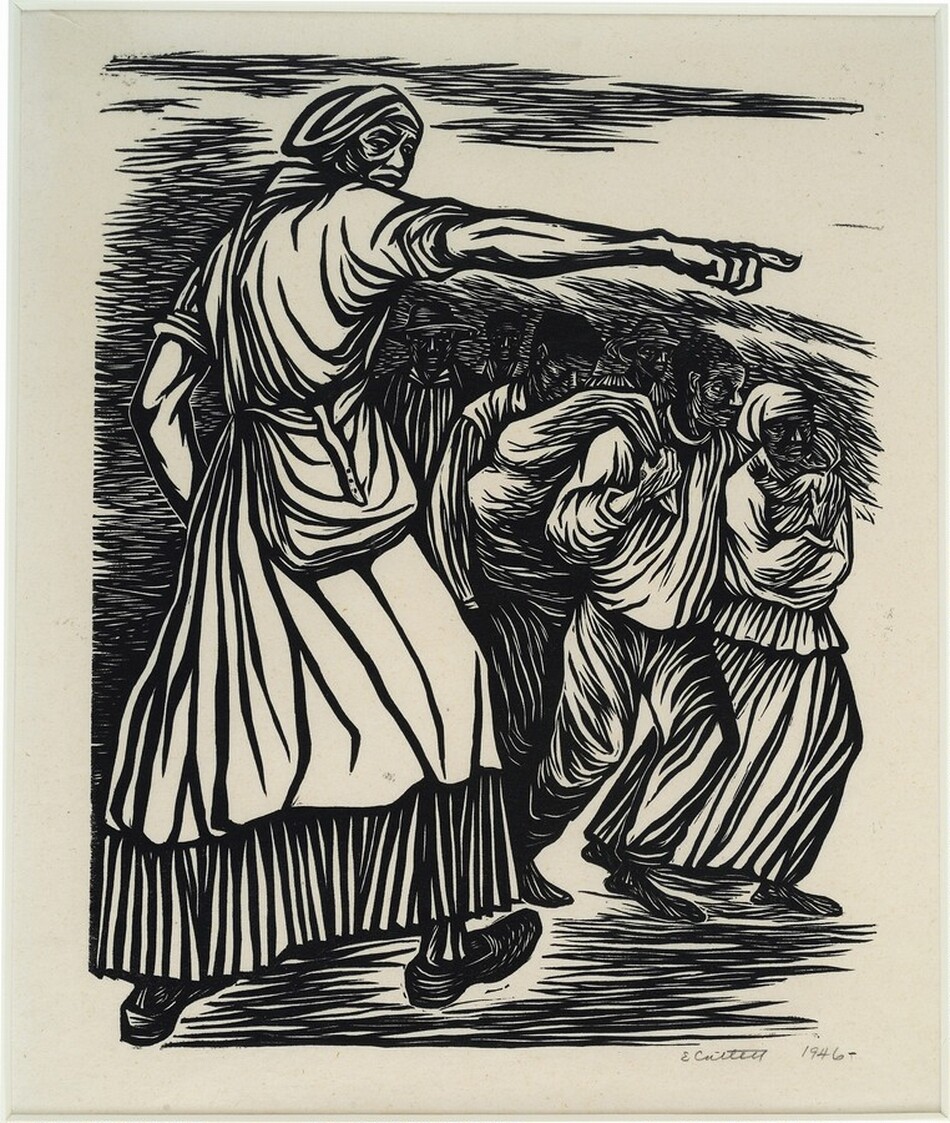

For the Rosenwald Fellowship, Catlett made a series of 15 linocuts originally called The Negro Woman, which she later retitled The Black Woman. The titles of the prints flow together to form a prose poem about the strength and suffering of Black women. Several of the prints depict renowned Black American women, including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Phillis Wheatley. Catlett represented the existence of these women as an act of resistance against racial oppression.

7. She was an international activist.

Elizabeth Catlett with her mother (left) and husband, artist Francisco Mora (right), at a protest in Mexico, c. 1950, Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Elizabeth Catlett advocated for civil rights and workers rights, and it came at a great personal cost. She was under surveillance by both the United States and Mexican governments. In the 1950s, she was arrested at a Mexican rail workers strike for being a “foreign agitator.” To avoid further arrests and deportation, she became a Mexican citizen in 1962. That same year, the US government labeled her an “undesirable alien.” Claiming that the TGP was a “communist front,” it barred Catlett and all TGP artists from entering the US.

For nearly a decade, she was repeatedly denied visas to return to her home country. In 1971, American authorities granted her a visa to return to the US to attend the opening of her solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Catlett’s American citizenship was finally reinstated in 2002. But even during her exile from the US, her commitment to the civil rights struggle of Black Americans never wavered.

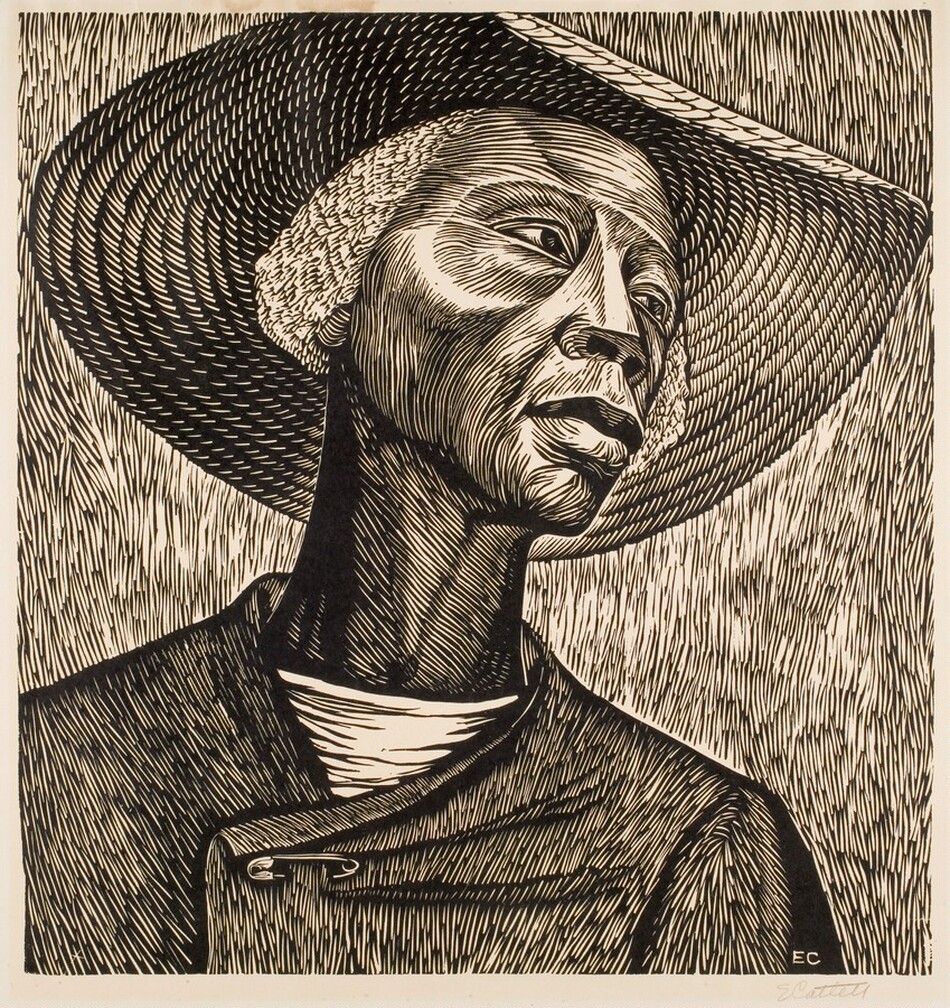

8. She championed the working class.

Catlett created powerful images of Black, Mexican, and Indigenous laborers—farmers, urban workers, street vendors, and teachers. Works like Sharecropper insist on the dignity and essential role of Black farmers; the sharecropper’s face may be sun-worn, but her head is held high and her gaze casts outward to the future. Catlett makes visual connections in her prints depicting Mexican campesinos, underscoring the shared struggle of agricultural laborers across the world. Catlett rejected the notion of art for art’s sake. She viewed the representation of ordinary people as an essential element of their empowerment.

9. She saw motherhood as central to her life and art.

Elizabeth Catlett, Mother and Child, 1983, mahogany, New Orleans Museum of Art, Museum purchase, Women's Volunteer Committee Fund, 83.71. © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Catlett had three sons: Francisco, Juan, and David Mora Catlett. She described becoming a mother as her most creative endeavor. While depictions of mother and child are canonical in the Western art, Catlett found few images of Black mothers. But in her own works, Black mothers became a recurring theme. Her renditions of Black motherhood powerfully show that they share the same desires of all mothers: to love, protect, and nurture their children.

As we can see from the embrace in Mother and Child, Catlett depicted the immense tenderness of a mother’s love. She also portrayed mothers as fiercely protective. In …and a special fear for my loved ones from The Black Woman series, Catlett captured women’s shared fears about the safety of their families.

10. She mastered many materials.

Brian Lanker, Elizabeth Catlett, 1988, gelatin silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Partial gift

of Lynda Lanker and a museum purchase made possible with generous support from Robert E. Meyerhoff and Rheda

Becker, Agnes Gund, Kate Kelly and George Schweitzer, Lyndon J. Barrois Sr. and Janine Sherman Barrois, and Mark

and Cindy Aron

“When I carve, I am guided by the beauty and the configuration of the material,” Catlett explained. And the materials she chose—clay, limestone, marble, onyx, and woods like primavera and mahogany—carried cultural significance. When the Smithsonian acquired her black marble sculpture Singing Head, she pointedly remarked, “Now they have one black marble” among their collection of white marble works.

Catlett looked to Mexican and African sculptural traditions for inspiration. In Singing Head, she took abstracted human forms found in African carvings as her starting point. She also learned techniques like Mesoamerican terracotta coiling and wood carving from Mexican sculptors Francisco Zúñiga and José L. Ruiz.

11. She made art for the public

Elizabeth Catlett, Floating Family, 1995, primavera wood, in situ photograph, Legler Regional Library, Chicago Public Library © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Catlett wanted her art to be accessible in public spaces that her communities frequented, not just in museums and galleries. Today, Catlett’s monumental sculptures adorn Atlanta’s City Hall, Howard University’s campus, a park in Harlem, and many more places across North America.

In 1994, the Chicago Public Library commissioned her to make a sculpture for Legler Regional Library, which primarily serves Black families on Chicago’s West Side. With a mother and child suspended horizontally, their arms outstretched and hands clasped, Floating Family hangs magically over the circulation desk. “I was excited just about the prospect of people sitting there, Black people sitting in that building, reading,” she said.

12. She was a friend and inspiration to many artists.

Through decades of teaching and activism, Catlett formed a wide circle of artists and friends. In Chicago she roomed with artist Margaret Burroughs and became friends with playwright Lorraine Hansberry, best known for writing A Raisin in the Sun. Burroughs and Catlett were also studio mates. They later reconnected at the TGP, where they collaborated with other artists on the print series Against Discrimination in the US.

When she moved to Harlem in 1942, fellow artist Ernest Crichlow introduced her to Jacob Lawrence and printmaker Robert Blackburn. In Mexico, she became friends with Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. She often created works in dialogue with those of her friends and collaborators. “We would meet at each other’s houses,” Catlett recalled, “and we would get together socially and discuss…creative things. People would read and we would look at each other’s work.”

Her legacy is felt deeply by artists working today. Baltimore-based printmaker LaToya Hobbs cites Catlett’s work as an inspiration for her monumental woodcut portraits of Black women, simultaneously revealing strength and softness. To celebrate the opening of this exhibition, Hobbs created a portrait of Catlett’s granddaughter Naima Mora.

Throughout her 96 years, Catlett remained true to her declaration: “I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black Revolutionary Artist, and all that it implies!”

You may also like

Article: 16 Black Artists to Know

Are you a fan of Glenn Ligon, Alma Thomas, or Gordon Parks? We’ve paired eight Black artists you might know with eight others to discover.

Article: Out of the Shadows, A Black Painter Finds Her Place in the Sun

American painter Lois Mailou Jones had to conceal her identity to exhibit this idyllic landscape — and achieved recognition on her own terms.