Freddy Rodríguez’s Quest to Express Dominican History in Art

Freddy Rodríguez once described his work as “historical, always.” For over five decades, the New York–based, Dominican-born artist critiqued European colonization, the ills of religion, and a brutal dictatorship in the Dominican Republic. Rodríguez’s work spans abstraction, collage, sculpture, and public art, often addressing Dominican history and culture.

Alejandro Anreus, curator, art historian, and Rodríguez’s friend, describes the artist’s passions: “identity, freedom, the weight of history, spirituality, resistance, and redemption.” All of these, he says, are represented across Rodríguez’s many styles.

Anreus, who is the Leonard A. Lauder Visiting Senior Fellow at the National Gallery's Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, adds that “open-ended adventures, quests are at the heart of his art.” In his art, Rodríguez was an adventurer, a seeker, and a renegade.

Rodríguez Becomes a New York Artist

Rodríguez was born in Santiago de Los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, in 1945. His family had artist roots: he was the grandnephew of Yoryi Morel, a costumbrista artist. Costumbristas painted everyday life, depicting local or regional customs. And Morel was a pioneering force in Dominican modernist art. Rodríguez fled to the United States when he was just 18. He arrived in New York City on Christmas Eve 1963.

When Rodríguez was growing up in the 1950s and early ’60s, there were no modern or contemporary art museums in the Dominican Republic. He had never seen abstract or geometric art.

In New York, one of his high school art teachers gave him a pass to the Museum of Modern Art. That is where Rodríguez first saw works by artists like Piet Mondrian. He especially gravitated toward Mark Rothko and younger minimalists like Frank Stella. Rodríguez knew that he’d later create his own abstract art, infused with his Dominican identity.

Rodríguez became a self-described true “New York artist.” Museums and art schools educated him and fed his mind. He majored in textile design at the Fashion Institute of Technology and studied painting at the Art Students League of New York as well as the New School.

Anreus describes New York in the 1960s and ’70s as “a place of experimentation and risk-taking, a ‘dense soup’ of visual, literary, and musical manifestations.” And he calls Rodríguez “un caribeño universal”: a “universal Caribbean” person who can thrive anywhere. Indeed, Rodríguez lived all over the city: in Greenwich Village, West Village, Chelsea, and Williamsburg. And while living mostly on the island of Manhattan, he made geometric art about the Caribbean island where he was born.

In some ways the city was Rodríguez’s safe haven, providing him with tools to succeed as an artist. But he also experienced hard times. His mother died nine months after he arrived in New York. And Rodríguez encountered xenophobia. He often said that it was through abstract geometric paintings that he found “an emotional balance.”

Geometric Paintings that Explore Nueva York

Rodríguez created his first geometric works in the early 1970s. He drew on graph paper beforehand for precision. Describing his laser focus on hard-edged abstraction, Rodríguez often quipped, “You have to be sober.”

He worked downtown on Broad Street or DeKalb Avenue and sketched on his lunch break, observing the city’s jagged architecture. Several untitled works from 1971 feature rectangular bars, large squares, straight-edged borders, all in muted earth tones. These initial geometric paintings represent Rodríguez’s New York: urban, intense, and disciplined.

Anreus describes Rodríguez’s dedication to painting, calling him “a painter’s painter, obsessed with the tradition, ruptures, and renewal of the medium.” A trio of large paintings from 1974—Danza de Carnaval, Danza Africana, Amor Africano—features sharp edges, vibrant colors, and pulsating rhythmic patterns. Here Rodríguez, a non-Black Dominican artist, honors the foundational African influences in our culture.

He created these paintings in his Chelsea loft studio on West 22nd Street. He also threw parties there, playing music by Afro-Cuban singer Celia Cruz and other Fania Records superstars. Afro-Latinx and Latinx musicians crafted salsa dura, the official soundtrack, so to speak, of ’70s Nueva York. The raw energy of salsa seeped into Rodríguez’s work.

Packaging Dominican Dictatorship in a Tourist Brochure

For decades, Rodríguez used his art to protest oppression. He read Latin American writers like Julio Cortázar and Pablo Neruda, inspired by the political resistance they described. (Rodríguez always said that, if not for his art career, he would’ve been a writer.)

During the political instability of the early 1960s, Rodríguez marched in student-led, leftist protests. And this political activity put his safety in jeopardy, forcing him to flee to the United States.

When he left the Dominican Republic, chaos was unfolding. After three decades of dictatorship, Rafael Trujillo had been assassinated in 1961. Two years later, the first democratically elected president Juan Bosch was overthrown. The nation was heading toward civil war, which would erupt in 1965.

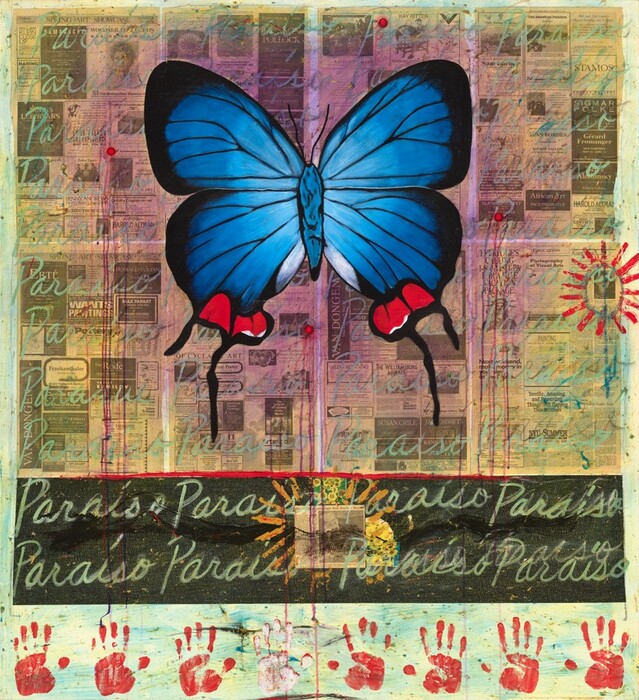

Last year, the National Gallery acquired Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, a large-scale collaged work made of acrylic paint, sawdust, and newsprint on canvas. In it, Rodríguez revisits his post-Trujillo trauma almost 30 years later.

The work mimics a morbid tourist brochure: three bullet holes drip blood and bloody handprints line the bottom of the canvas. They symbolize the atrocities of Trujillo’s regime.

A blue butterfly contrasts with these violent elements. Rodríguez uses it to represent a silent witness, an observer of colonial brutality since the 15th century. While we don’t know whether the artist intended this reference, for many viewers the butterfly also conjures up the Dominican national heroes, the Mirabal Sisters. These three women revolutionaries, known as the “Mariposas” (butterflies), were assassinated by Trujillo’s henchmen in 1960. Today, violence against women in the Dominican Republic persists—the country has the second highest femicide rate in Latin America.

Rodríguez scrawled paraíso (paradise) in cursive 44 times across this canvas, which is part of a series also called “Paradise.” He contrasted the tourist wonderland with the history of violence in the Dominican Republic. But even today, tourists who love spending idyllic vacations at Caribbean resorts can at times be participating in a violent system. Knowingly or not on the tourists' part, it can come at the cost of (usually Black) resort workers experiencing labor and sexual exploitation.

The background is a collage of New York Times arts sections from 1990. There are endless ads for exhibitions by 20th-century European and white American artists such as Sigmar Polke and Jackson Pollock. Rodríguez, a Dominican and Latine artist, stands up to the exclusion and rejection he faced from an art establishment that clearly privileges white artists.

“Rodríguez’s art world critique began in the 1980s. It parallels critiques from other artists of color and women artists, such as Howardena Pindell and the Guerilla Girls,” says National Gallery chief curatorial and conservation officer E. Carmen Ramos. “These artists and collectives publicly called out the racial and gender exclusions of museums and the broader art world. In his paintings, Rodríguez pointedly inserted himself into the history of modern and contemporary art.”

Ramos, a Latinx art specialist, studied Rodríguez’s work for years, including it in solo and group exhibitions. Ramos had a close relationship with the artist and spearheaded the acquisition of his work at the National Gallery.

Religious Traditions Surviving Colonization

The National Gallery also recently acquired Casabe y Cruz II. Rodríguez made this work in 1991, one year before the planned celebration of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus supposedly “discovering” the Caribbean.

“Like many Latinx, Latin American, and Native American artists, Rodríguez was critical of these worldwide celebrations,” says Ramos. “Colonizers imposed European beliefs and ideas to suppress Indigenous and African beliefs. This set the stage for land grabs, resource extraction, and forced labor. Rodríguez saw the Conquest as a spiritual event, but religion was used a tool of domination.”

Made of acrylic, sawdust, and glass, Casabe y Cruz II is sparse yet moving. The gold cross centered at the top of the grainy, white canvas represents Christianity. The tondo (round) format recalls 15th-century paintings from the Italian Renaissance, like Michelangelo’s Holy Family. It evokes the communion bread—typically a flat white wafer. In the Catholic ritual of the Eucharist, the bread stands in for the body of Jesus Christ.

The circular painting also resembles casabe, a bread popular across the Caribbean and Latin America as well as their diasporas. Derived from the yuca roots of the cassava plant, this flatbread originated with Indigenous peoples such as the Arawaks and the Caribs. Taínos (an Arawak group) inhabited the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and the rest of the Greater Antilles. Casabe preparation was a communal activity among Taíno women.

“Casabe y Cruz II blends two opposing symbols,” explains Ramos. “Both are circular and whitish in color, both are eaten. Christianity was meant to wipe out Native and later African beliefs and practices, but they actually endured.”

Rodríguez carefully chose white, which is associated with the "pure" and "immaculate" in Christianity, as the sole color on the canvas. Christian colonizers claimed to be “purifying” Indigenous and African religions that they deemed “barbaric.” The Spanish Catholic Church built up white supremacy to colonize, enslave, and force religious conversion on Taínos, other Indigenous groups, and eventually Africans.

The white circle also represents West and Central African spiritualities merging with Catholicism to survive. This birthed Afro-syncretic religions across Latin America, including Dominican Vudú (The 21 Divisions), Haitian Vodou, Cuban Vodú, and Santería.

Like Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, Casabe y Cruz II is part of a series of works—“Colonization.” Rodríguez enjoyed producing in series. “It keeps me busy, it keeps me investigating,” he said. Ever the truth teller, he thrived in studying and uncovering.

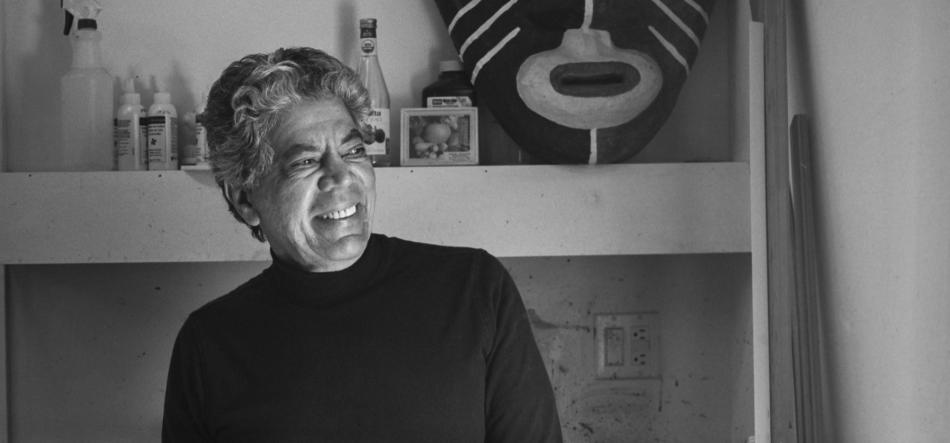

Banner image: detail of a photograph of Freddy Rodríguez in his studio in Queens, New York, in 2016. Photo by Manolo Salas.

You may also like

Article: Miguel Luciano’s Portrait of a Puerto Rico in Crisis

The artist confronts us with the contemporary Puerto Rican experience.

Article: 9 Latinx Artists You May Not Have Heard Of

Learn about the lives and works of artists of Latin American descent working in the United States from the 1930s to today.