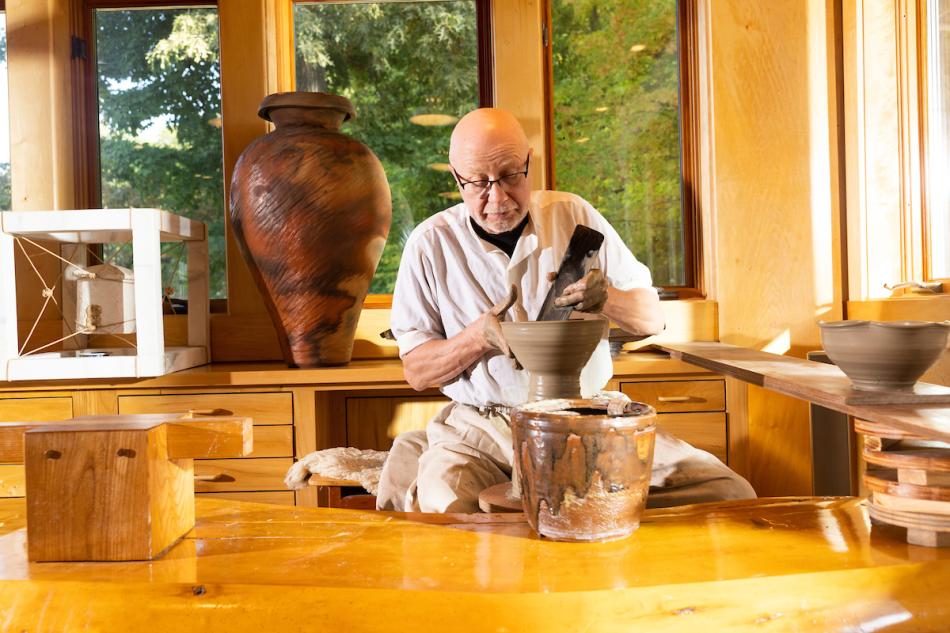

Potter Richard Bresnahan Navigates an “Eco-mutual” Future

“I’m lost,” Richard Bresnahan remembers telling his mentor, Sister Johanna Becker, Order of Saint Benedict, in 1975. He was a junior at St. John’s University in central Minnesota, and he had some choices to make. “I want to become a potter, but I don’t know how to build kilns. I don’t know how to dig clay or make glazes out of natural materials. I come from a very poor family in North Dakota, and I can’t afford graduate school. I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

Becker sent him to an island 6,000 miles away. In rural Kyushu, Japan, Bresnahan apprenticed under master potter Takashi Nakazato. Nakazato’s family had for 13 generations made Karatsu ware, a rustic style of functional ceramics named after their city.

When Bresnahan returned to Minnesota, he was no longer lost. He had been gifted a conceptual map, a way of living and making that set him on a spiritual, creative, and ecological path for life. He became the university’s first artist-in-residence, building a massive kiln and a vast community of artists. Today, an intimate relationship with the planet, which he calls “eco-mutualism,” is driving his work.

A North Dakota Childhood

Bresnahan was born in Fargo in 1953 and raised in rural Casselton, North Dakota. His childhood taught him the power of resourcefulness in uncertain times. He worked on relatives’ farms and at his dad’s grain elevator. And he learned what it takes to survive as small family farmers: reusing materials, repairing machinery, living off what the land gives, and banking those gifts for the future. “Coming out of the Depression, can you imagine how happy my great aunts and uncles and my grandparents were when they were able to buy their first grain bin? It only held 1,500 bushels, but they had control over their seeds for the first time.”

The region would be hit viciously in the years that followed. The 1980s farm crisis and ensuing recession would cause waves of foreclosures and farmer suicides.

“Drive the prairies of North Dakota today,” Bresnahan says. “The farmhouses are gone, the barns are gone. But you see the sentinels, those grain bins, those last remaining joys of farming families that are gone.” During his apprenticeship in Kyushu, he found a way of living that resonated with his North Dakota childhood: communal, resourceful, hyperlocal, and sensitive to the earth.

A Hyperlocal, Global Art Tradition

Becker was a member of Saint Benedict’s Monastery and a scholar of Asian ceramics. Before sending Bresnahan off to Karatsu, she gave him some advice.

“Your responsibility is to learn all you can of the processes, the cultural stimulations, the reasons why all of this has been done. Your responsibility is to bring that back to this culture and change it, because it doesn’t exist here.”

“Don’t eat fugu sashimi,” she added, holding out a Japan Times clipping about an actor who’d just died after eating raw puffer fish liver.

Bresnahan took this to heart. After nearly four years, he received the distinction of master potter, the first westerner in the Nakazato tradition to do so. He returned in 1979—alive and carrying journals and slides documenting all he had witnessed. He also had a proposal: to activate what he’d learned, but with a deeply local difference. He wanted to make pottery from indigenous materials.

He’d fuse practices and philosophies from Karatsu with the values of the Catholic monastics who founded St. John’s. The Benedictines prize hospitality, land stewardship, and self-sufficiency. Bresnahan was named the university’s first artist-in-residence and launched an apprenticeship program.

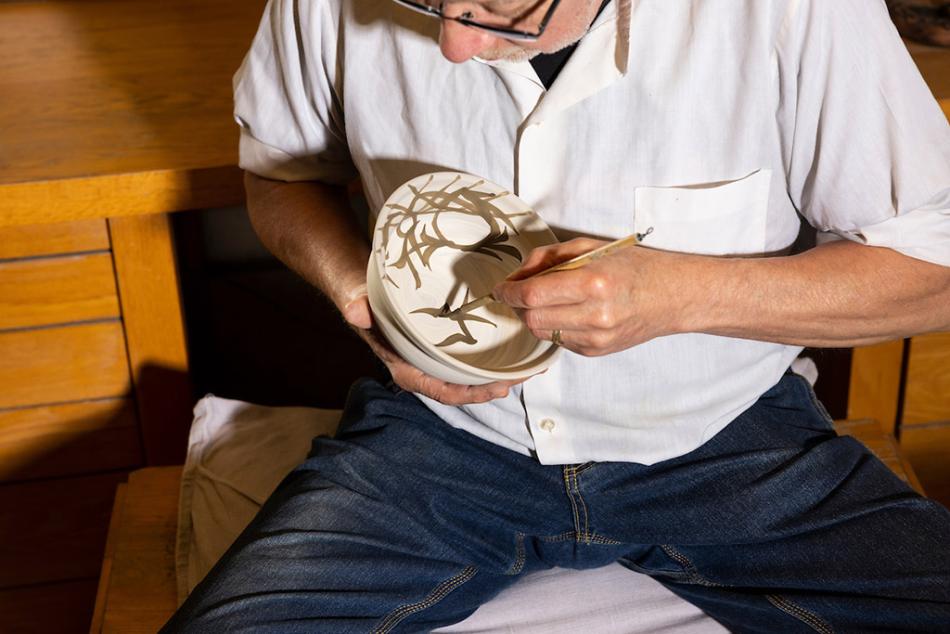

Soon after, he came upon a road project near campus that had exposed a massive clay deposit estimated to be 144 million years old. He brought enough clay back to supply the studio for 300 years. Then he began to play, testing how various materials create different colors and effects in glazes. He’d get donations of wild rice hulls from the White Earth and Red Lake Indigenous nations. And he’d mix in waste granite dust from a quarry in nearby St. Cloud to make tenmoku glazes. (A tenmoku glaze is an iron glaze that fires to a dark brown tone.) Flax straw from his uncle’s North Dakota farm made blue-tinged glazes, he discovered. Discarded sunflower seed hulls from grain distributor Cargill yielded golden hues.

This experimentation is part of what sets Bresnahan’s art apart, says Matthew Welch, chief curator at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. One of Bresnahan’s early supporters, Welch has organized several exhibitions of his works. “The artists that we really take note of in the great traditions in Japan are the ones that are pushing the envelope forward,” he says. “They’re not bound by tradition. They’re inspired by it, but they’re constantly experimenting. And if Richard brought back anything, it’s that.”

The Community at the Johanna Kiln

Bresnahan also began designing kilns. In 1995 he built the Johanna Kiln, still in use today. Eighty-seven feet long with three chambers, it’s the largest wood-fired kiln in North America.

Kiln making is a complicated affair, one that requires many hands to build and use. “They’re enormous undertakings,” says Welch. “The Japanese make massive kilns because firing them is a huge use of resources and becomes a community event. So lots of potters typically would put their works into a kiln. They’d all participate.”

It can take up to nine weeks to load the Johanna Kiln to capacity—about 12,000 works created by artists on and off campus. Before each firing, the kiln is blessed and purified with salt, rice, and sake in the Japanese tradition. Some 60 volunteers feed wood from the St. John’s Arboretum to keep the fire going.

“It’s around the clock for 10 days, so it’s fully a community undertaking,” says Welch, one that shows “that a potter is embedded in the community in a way that maybe other artists aren’t.”

Anne Meyer Jarrell, an apprentice in the studio from 2004 to 2006 and a shift lead at every kiln firing since, celebrates Bresnahan as a community leader.

“Richard is a father figure and the nurturer of an incredibly large and close group of people. But he also is very driven and focused on what he wants to accomplish,” she says. “It’s seemingly at odds with the sense of selflessness that you associate with someone standing behind a large community. But you need that kind of clarity and drive to be the person that others fall in line behind if you want to create something larger than one person can accomplish.”

Says Welch, “With Richard, there is this sense of community that is the antidote to that idea of the divinely inspired individual artist that we typically think of.”

Those relationships and that unique vision are at the center of Bresnahan’s most recent, and largest, work.

Art as a Storehouse for the Future

Richard Bresnahan, Kura: Prophetic Messenger, 2020. Photograph by Paul Wegner. Located in the Jon Hassler Sculpture Garden, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, MN. Gift of John and Lois Rogers. Image from the book Kura: Prophetic Messenger, by Richard Bresnahan; Margaret Bresnahan, editor; Kura Book Publishing LLC, 2021, page xxiv.

Richard Bresnahan, Kura: Prophetic Messenger, 2020. Photograph by Paul Wegner. Located in the Jon Hassler Sculpture Garden, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, MN. Gift of John and Lois Rogers. Image from the book Kura: Prophetic Messenger, by Richard Bresnahan; Margaret Bresnahan, editor; Kura Book Publishing LLC, 2021, page xxiv.

After having quintuple bypass heart surgery in 2017, Bresnahan says he “started seeing this particular idea of a sculpture project in the dream world.” Mental images began to appear for what would, in 2020, become Kura: Prophetic Messenger, the first permanent sculpture for the Jon Hassler Sculpture Garden at St. John’s.

The work weaves together the ideas, people, and practices Bresnahan holds dear. Like his ancestors’ grain bin, it’s a literal storehouse of seeds. It is based on the Japanese kura, “the most sacred architecture of the Shinto tradition.” But it also includes texts that he thinks will guide people well past his lifetime.

At the center of the work is a cylindrical kura suspended in the air. Inside, there is a stainless steel chamber. The chamber holds a ceramic jar, which in turn holds a scroll letterpressed by local artist Mary Bruno. It bears the text of The Rule of Saint Benedict, the book that has guided Benedictine monks for centuries.

Around the kura are earthenware jars packed in wild rice hulls. They hold 182 varieties of seeds for the Indigenous Three Sisters: 28 varieties of corn, 82 of beans, and 72 of squash. The seeds are hermetically sealed to be viable whenever needed, even in hundreds or thousands of years. Accompanying each container is a write-up about each seed.

There are also texts about people, each assigned to a specific seed, who have influenced Bresnahan. Some of the names are familiar: Winona LaDuke, Buckminster Fuller, John Prine. Others, more personal to the sculptor and his practice, include his apprentice Anne Meyer Jarrell, wife Colette Bresnahan, and late mentor Johanna Becker as well as members of the Nakazato family.

But this isn’t mere conceptual art, meant to provoke deep thinking. Bresnahan sees it as a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency tool kit.

“Starvation will come here at some point. We’re not going to Norway to some freezing hole in the mountain [the Svalbard Global Seed Vault] and getting the seeds out,” he says. “[This sculpture] contains the whole nutrition for 12 communities, tens of thousands of seeds. To save people’s lives.”

The project embodies Bresnahan’s approach to land stewardship and climate change. He sees this as a cognitive shift our culture needs, from “sustainability” to eco-mutualism. “Ecological mutualism means we include humanity.” In this sculpture, as in his nearly half-century of practice, Bresnahan has mapped out both the environmental and relational terrains we must navigate to survive a perilous future.

You may also like

Article: From Old Car Tires, Chakaia Booker Reveals Beauty and Devastation

Transforming discarded tires into monumental sculptures, the artist reflects on the environmental impact of our daily commutes.

Article: Sentinels and Sprawl: Photographs of the Saguaro Cactus

As the presence of humans changes the Sonoran Desert, photographers capture the impact on the saguaro cactus.