Who Is Ellsworth Kelly? 10 Things to Know

What did Ellsworth Kelly want you to feel? In a word: joy.

One hundred years after the American artist’s birth, learn about his life and inspirations, from his love of birdwatching and time in Europe during World War II to his creative process and the building he designed.

1. Kelly started making art as a child.

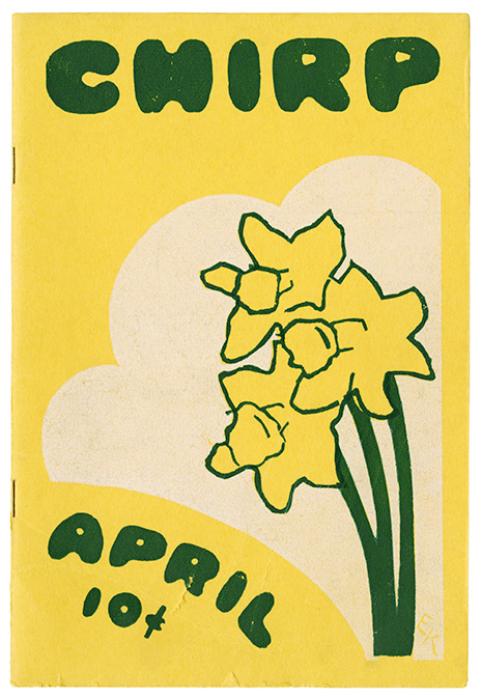

Ellsworth Kelly, Cover of Chirp (Oradell Jr. High School journal), 1938, linoleum print, image Courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio, Artwork © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

Ellsworth Maurice Kelly was born in Newburgh, New York, on May 31, 1923. He spent most of his childhood in New Jersey.

Encouraged by his teachers, Kelly started experimenting with painting and sculpture in elementary school. He was listed as “best artist” in his junior high school yearbook.

2. Kelly loved birdwatching, which drove his fascination with color.

Kelly’s mother and grandmother introduced him to birdwatching when he was six. And he soon learned about the work of ornithologists (bird experts) and illustrators John James Audubon and Louis Aggasiz Fuertes.

Birdwatching would remain a lifelong hobby. Kelly said in an interview that “colour fascinated [him] in birds—red streak here, blue streak there, green streak here.” Watching the active, colorful creatures, he became interested in the relationship between color and space.

3. Kelly used his art skills while serving in a “Ghost Army” during World War II.

Ellsworth Kelly with screenprints, Fort Meade, Maryland, 1943, image Courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

In 1942 Kelly left art school at Pratt Institute in New York City to volunteer for the army. Kelly was based in Fort Meade, Maryland, for training. While there, he often visited the National Gallery.

Eventually his battalion joined the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known today as the “Ghost Army.” The Ghost Army made inflatable tanks and other tricks to confuse Germany about the location and scale of the Allied forces. Kelly and other artists taught soldiers to paint the fake vehicles.

4. Kelly studied medieval art and architecture.

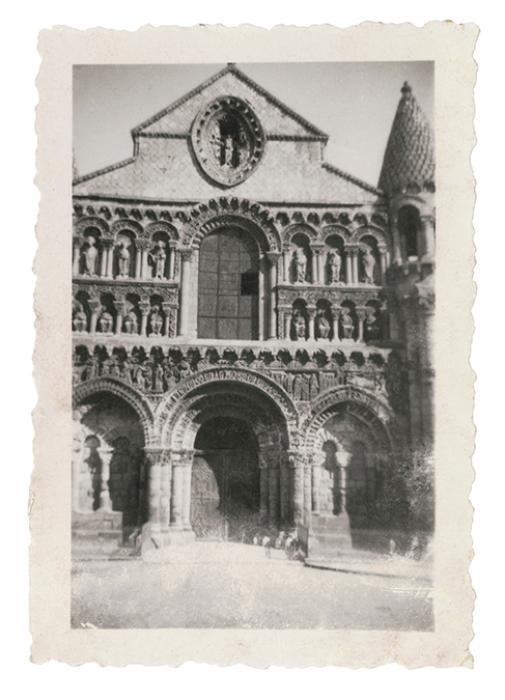

Ellsworth Kelly, West façade, Notre-Dame-la-Grande, 12th-century, Poitiers, 1949, gelatin silver print, image Courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio, Artwork © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

After training, the Ghost Army was sent overseas. Kelly was stationed in England, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. While most museums were closed because of the war, Kelly explored the countries, making watercolors and drawings of what he saw.

Visiting the historic churches and towns had a lasting impact on his art. It began a lifelong interest in Romanesque and Byzantine art and architecture that would influence his ideas about the relationship between painting, sculpture, and architecture.

5. Kelly developed his abstract style while living in postwar France.

After the war, Kelly used the financial support offered through the G.I. Bill of Rights to continue his studies at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (then the Boston Museum School). Following graduation, he moved to Paris. He enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts but spent more time in the city’s museums than in class.

While in France for the next five-plus years, Kelly crossed paths with artists Alexander Calder, John Cage, Jean Arp, and Constantin Brancusi. His style evolved from representational (showing figures and forms as he saw them) to abstract, with many solid shapes of color. The five-panel construction of Tiger, one of his abstractions from the time, may have been inspired by Matthias Grünewald's Isenheim altarpiece.

6. Kelly often started with drawings.

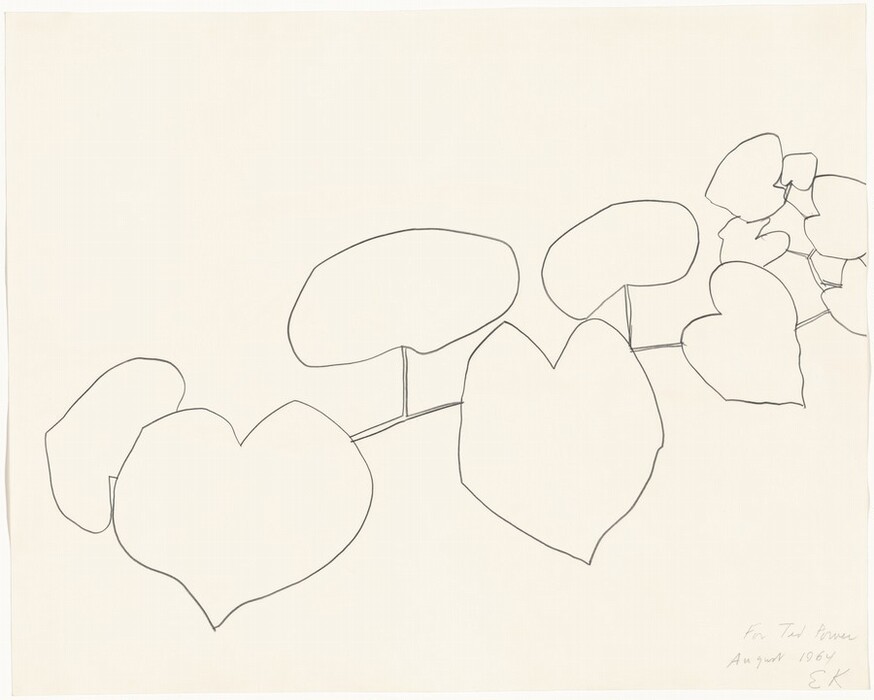

“Drawing, for me, is the beginning of everything,” Kelly once said. Working on paper was a key part of his creative process.

Before painting, Kelly would often make a sketch or study in pencil, gouache, ink, or collage. He would rearrange the elements and colors until he was satisfied. Sometimes, he would revisit earlier studies for new ideas.

The compositions of many of Kelly’s paintings come from nature or forms he observed in the world. Kelly made line drawings of their essential shapes, like this Wild Grape.

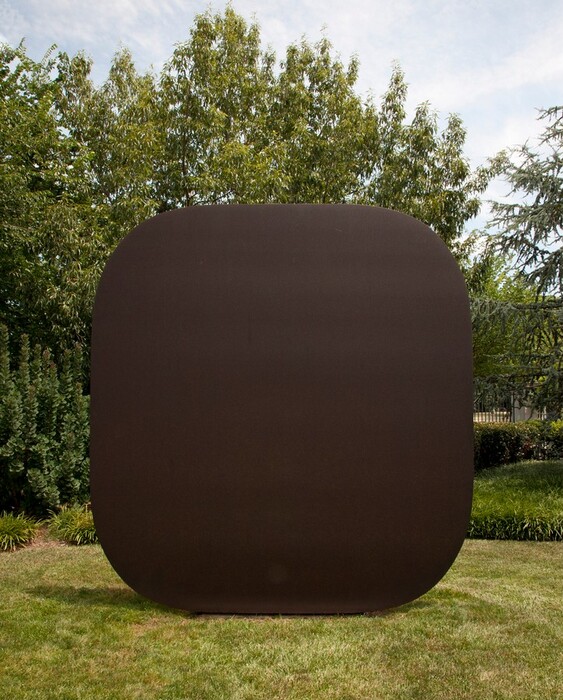

7. Kelly also made large-scale sculptures.

After moving to upstate New York in 1970, the artist began making large, outdoor sculptures. Kelly often played with shapes he had used in paintings, freeing them from a wall.

The shape of this steel sculpture came from a French kilometer marker. Its title, Stele II, and shape also refer to commemorative stones from ancient Mayan and Egyptian cultures. Like tombstones, stelae (the plural of stele) stand upright.

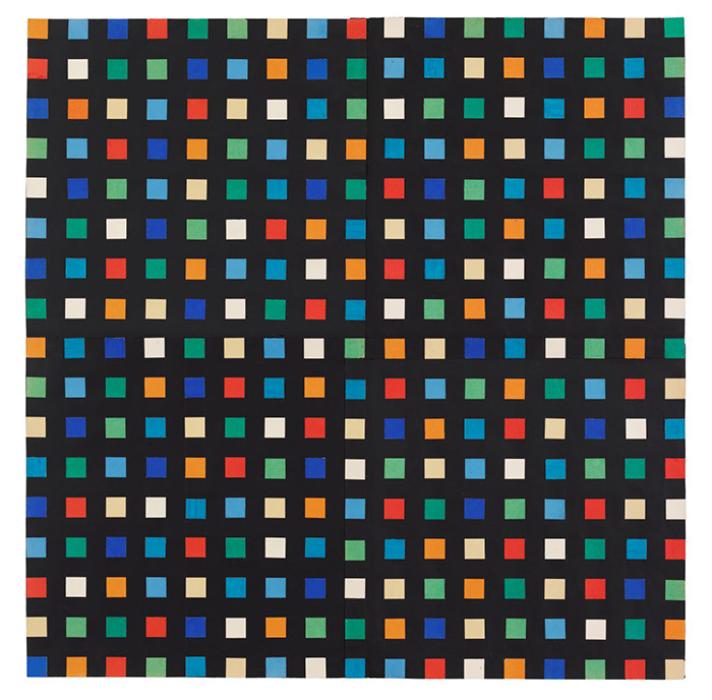

8. Kelly played with chance.

Ellsworth Kelly, Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance IX, 1953, collage on paper, image courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio, Artwork © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

Rather than carefully composing artworks, Kelly would sometimes leave them entirely up to chance. To create works like Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance, Kelly assigned numbers to each color and then randomly selected the arrangement. This interest in chance was part of a larger effort to remove his hand from his art.

When Kelly first began making abstract paintings, the popular style was abstract expressionism, which filled paintings with expression and gestures. Instead, Kelly made paintings without any hint of the artist’s hand. He wanted us to focus on the experience of shapes and colors in space.

9. Kelly designed a building.

The "tumbling squares" motif in "Austin", an immersive work of art and architecture designed by artist Ellsworth Kelly and built on the grounds of the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, United States. Larry D. Moore, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons, © 2018 Larry D. Moore

In 2015 Kelly gave the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin a monumental gift—his design for a building.

The layout of Austin draws on the stained glass–filled, Romanesque churches he saw in Europe. The space is organized in a cross, with arched ceilings and three sets of stained-glass windows in a spectrum of colors. We can think of this work as the culmination of his career: an environment where space, color, and shape all come together.

10. Kelly’s legacy continues 100 years after his birth.

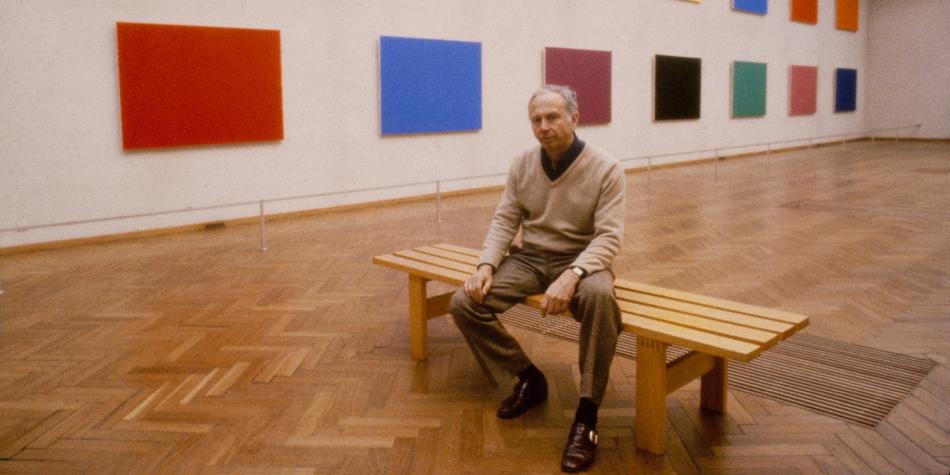

A visitor takes in Ellsworth Kelly’s Color Panels for a Large Wall, 1978, oil on canvas, Purchased with funds provided by The Glenstone Foundation, Mitchell P. Rales, Founder, 2005.87.1

This year marks the centennial of the artist’s birth. By the time he died at age 92 in 2015, Kelly had received countless awards including the National Medal of Arts. He is one of the most important postwar American artists, and his works are in museums around the world. Kelly’s husband of more than 30 years, photographer Jack Shear, carries on the artist’s legacy as the director of the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation.

Ultimately, his art achieves one of Kelly’s greatest wishes—to make people happy. In an interview a few years before his death Kelly said, “I wanted to give people joy.”

Banner detail: Ellsworth Kelly with Color Panels for a Large Wall at “Ellsworth Kelly: Paintings and Sculptures 1963–1979,” Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1979, image Courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio, Artwork © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

You may also like

Article: George Morrison Gets His Due

The Minnesota painter merged abstract expressionism with traditional Ojibwe values.

Article: Your Tour of Latinx Artists at the National Gallery

Use our guide to explore works by Latinx artists on view in our galleries.