Who Is I. M. Pei? 10 Things to Know

What inspired the Chinese American architect to make some of the world’s most beautiful buildings? Read about I. M. Pei’s influences, the first building he designed, and his celebrated structures.

1. Pei’s childhood shaped his creative approach.

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in Guangzhou, China, on April 26, 1917. His family moved to Hong Kong when he was one and then to the quickly modernizing Shanghai when he was 10. Pei spent several summers in Suzhou, the home of his ancestors. According to Pei, his family’s garden, known as Shizilin (Lion Grove Garden), taught him that “the hand of man joined with nature becomes the essence of creativity.”

A photograph from the early 1920s shows I. M. Pei on the far left along with his grandfather (at center) and father Tsu-yee Pei and mother Lien Kwun (standing), Library of Congress.

2. Pei met famous architect Le Corbusier.

Pei came to the United States in 1935 to study architecture at the University of Pennsylvania before transferring to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). While browsing MIT’s library he discovered the writings of Le Corbusier, who pioneered modernism in architecture. By coincidence, Pei was able to spend two days with Le Corbusier when the Swiss-French architect visited MIT in 1935. Pei considered those two days “the most important days in [his] architectural education.” Pei received his master of architecture degree in 1946 from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Pei (third from left) with his professor and classmates at MIT during his sophomore year (1936–1937), Library of Congress.

3. Pei found inspiration in cubism.

Pei credited the 20th-century art movement of cubism with the origin of modern architecture. He considered architecture a form of art like painting and sculpture because it explores how spaces are shaped by solids and their opposite (voids)—and the effect of light on both.

Pei specifically cited his work for the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the Everson Museum, and the National Gallery’s East Building as directly influenced by cubism. Cubist works by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris are on view in the East Building’s galleries.

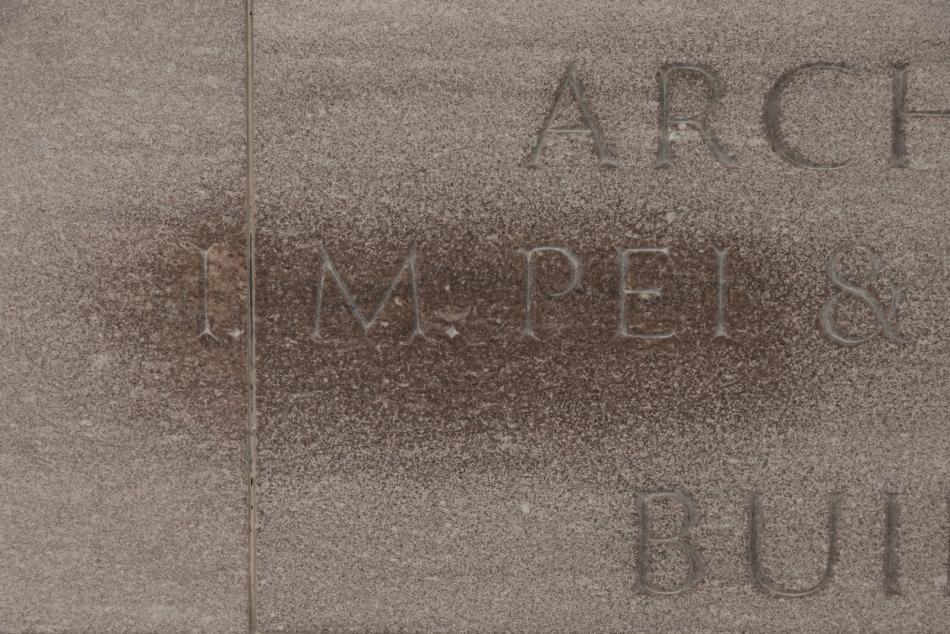

4. Pei’s first constructed design is in Atlanta.

In 1948, Pei was recruited to head the architecture department for real estate development firm Webb & Knapp. The following year, he designed a 50,000-square-foot office for Gulf Oil in Atlanta, Georgia.

Pei used marble for an exterior curtain wall, and Architectural Forum stated that, “with one bold stroke, Architect Pei freed traditionally monumental marble from its use as a thin veneer on costly masonry walls and turned that veneer into the wall itself.”

In 1955, Pei established his own firm, I. M. Pei & Associates, later renamed I. M. Pei & Partners. Today the firm is known as Pei Cobb Freed & Partners.

A 2013 photo of Pei’s first building for Gulf Oil in Atlanta, Georgia. Image by Keizers via Wikimedia Commons.

A 2013 photo of Pei’s first building for Gulf Oil in Atlanta, Georgia. Image by Keizers via Wikimedia Commons.

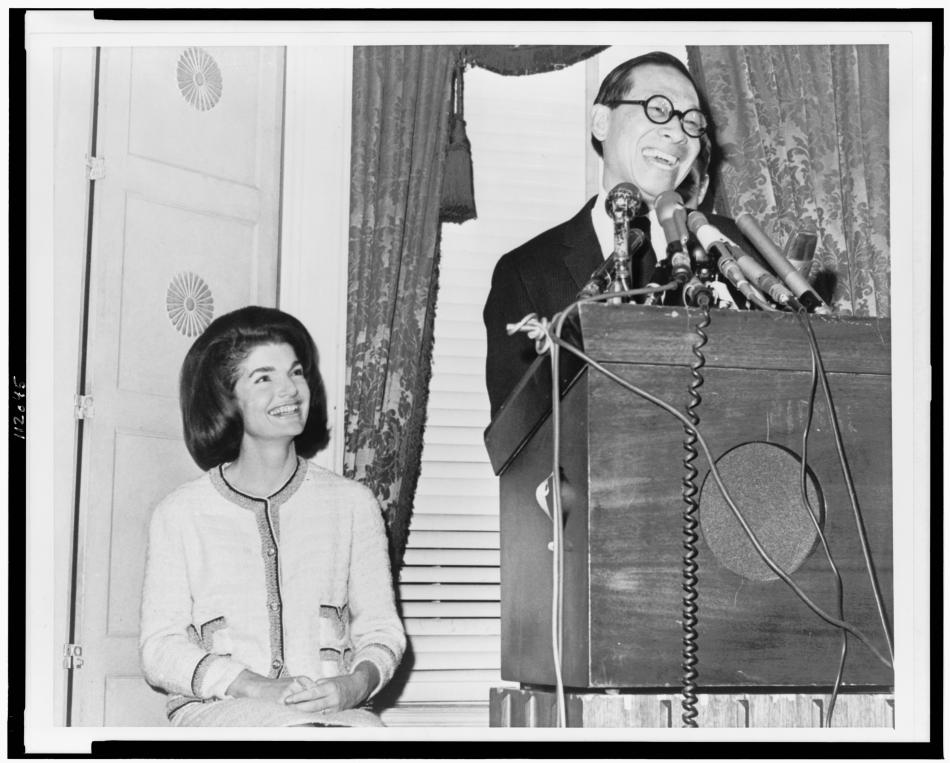

5. Pei designed the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library in Boston.

In 1964, Pei was commissioned to design the Kennedy Library. Jackie Kennedy chose Pei after considering many notable architects, including Louis I. Kahn and Mies van der Rohe. Pei was not well known at the time, but Kennedy made what she called a “really an emotional decision. He was so full of promise, like Jack [John F. Kennedy]; they were born in the same year. I decided it would be fun to take a great leap with him.”

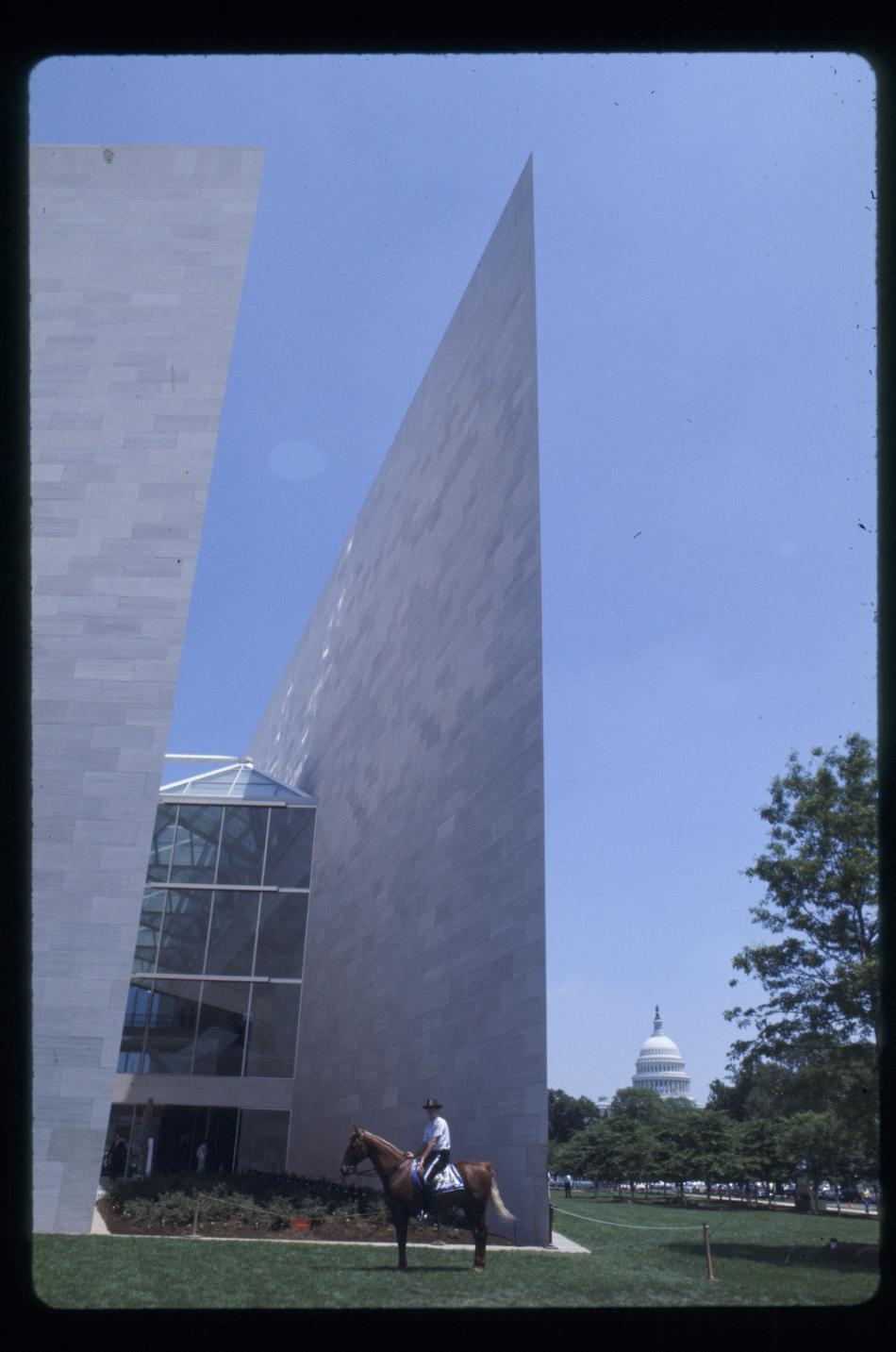

6. Pei’s design for the East Building is centered around triangles.

In 1968, the trustees of the National Gallery chose Pei to design the East Building. Congress had reserved a plot of land for the second building when the museum was established in 1937. Pei solved the problem of the site’s irregular shape by dividing it into two triangles, a concept he initially sketched on the back of an envelope during a flight from Washington, DC, to New York.

The final design for the East Building, which opened to the public in June 1978, includes the key elements of Pei’s practice: manipulating mass, volume, light, and materials with an eye to how people experience architecture.

Pei considered the East Building one of his most important works. “It was not until the National Gallery that I felt I had found a conviction about what architecture meant,” he said.

7. Pei designed the glass pyramid at the Louvre.

In 1981, French President François Mitterrand started a project to expand, renovate, and reorganize the Louvre museum in Paris. Mitterrand and Émile Biasini, who managed the project, both visited the East Building in the early 1980s and saw the glass “crystals” Pei had created on the plaza before selecting him as the architect.

Reorganizing the Louvre’s galleries and offices required a new, central public entrance. Pei brought the museum together around a new entrance housed in a large glass pyramid in the Louvre’s courtyard. While the pyramid was originally controversial, it has become one of Pei’s—and Paris’s—most iconic structures.

8. Pei won the Pritzker Prize.

The Pritzker Prize is commonly known as the Nobel Prize of architecture. After receiving it in 1983, Pei used his prize money to establish a scholarship fund for Chinese students to study architecture in the United States.

Pei has also been awarded the Gold Medal for Architecture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects, among many other honors.

Pei with Jay and Cindy Pritzker, 1983, courtesy of The Hyatt Foundation/The Pritzker Architecture Prize.

9. Pei described the process of designing the East Building, and the oral history is in the National Gallery Archives.

I. M. Pei & Partners donated the records of their work on the East Building to the National Gallery Archives in 1986. The archives also hold records related to the East Building, including models, specifications, photographs, correspondence, oral history interviews, press releases, and materials on later renovation projects.

To learn more about the archives, you can schedule a research appointment or ask questions by emailing [email protected].

Early conceptual sketch for the East Building by I. M. Pei, 1968, National Gallery Archives.

Early conceptual sketch for the East Building by I. M. Pei, 1968, National Gallery Archives.

10. Pei was 102 years old when he died.

Pei died in New York City on May 16, 2019, shortly after his 102nd birthday. He was one of the most important architects in the United States and the world. New generations of architects continue to study his designs.

Many architecture students and enthusiasts make the pilgrimage to see the East Building. You can see marks where their hands have reverently touched the carving of Pei’s name in the Atrium and the sharp 19.5-degree corner outside, commonly known as the “Knife Edge.”

You may also like

Article: 12 Documentary Photographers Who Changed the Way We See the World

Photographers of the 1970s revolutionized the medium through innovations of both style and subject.

Article: Centering Asian Artists in the American Story

Asian Americans are often left out of view of US history. But their lives—and their art—are an essential part of the nation’s story.