Painting Climate Change in the 17th Century

The world has warmed by more than one degree Celsius since the late 19th century, and it is on course to warm by another two degrees by the end of this century. The combination of the speed, likely magnitude, and human cause of this global warming make it unprecedented in the history of our species.

Yet this is not the first time Earth’s climate has changed. In the 13th century, the climate of the Northern Hemisphere started to cool due to natural causes. Although cooling varied over time and from place to place, in general it persisted for several centuries. This period is commonly referred to as the Little Ice Age. Global temperatures declined by just a few tenths of a degree Celsius—significantly less dramatic a change than our current warming trend. Nevertheless, regional effects were often severe, including catastrophic droughts, torrential rains, and entire years in which winter never fully gave way to spring and summer.

Global temperature anomalies over the past 2,000 years. Dark blue indicates the coolest temperatures, while dark red indicates the warmest. The Little Ice Age (which can be dated to approximately 1250–1850) is outlined at right, just before the current period of extreme, human-caused warming. Graphic by Ed Hawkins using data from PAGES2k and HadCRUT4.6

Some of the disasters of the Little Ice Age may sound familiar. Indeed, many scholars study how people of the past coped with extreme weather to better understand how our societies might respond to global warming. The 17th-century Low Countries (modern Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) provide striking models of just how adaptive and resilient people can be in the face of a changing climate. But they also provide warnings about how climate resilience can create or worsen inequality.

Fortunately, the 17th century has furnished us with a unique resource: millions of paintings, prints, and drawings, created by thousands of artists across the Low Countries, that depict elements of everyday life. By 1650 the inhabitants of Holland—the wealthiest province of the Dutch Republic, the precursor state to today’s Netherlands—collectively owned around 2.5 million paintings. Many of these paintings seem to reflect the presence of the Little Ice Age and record its consequences for ordinary people. Some remarkable examples are included in the National Gallery’s collection.

These include stunning winter landscapes, which seem to recreate, with plausible detail, real-life gatherings in frigid weather. For example, Adam van Breen painted Skating on the Frozen Amstel River amid a sequence of chilly winters in the Low Countries, and in 1646—when Jan van Goyen painted Ice Scene near a Wooden Observation Tower—winter was even colder.

Although there were forces other than climate change that influenced how artists chose and depicted their subjects, icy landscapes do shed light on how the Dutch adapted to a cooler climate. The coastal Low Countries were crisscrossed by waterways that allowed for the efficient transportation of goods, people, and information.

Paintings like those of Van Breen and Van Goyen accurately portray how ordinary people across the Low Countries used sleds and ice skates—a Dutch invention—to keep these transportation networks open in cold weather. To maintain crucial shipments of goods that were easier to send by water, intrepid traders even designed specialized icebreaker ships.

Because the Little Ice Age did more than alter temperature, we can look beyond icescapes to see how artists depicted its telltale weather.

Ludolf Backhuysen’s Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast is only one particularly beautiful example of hundreds of Dutch and Flemish paintings that portray ships imperiled by storms. In the waters around the Low Countries, such storms may have been especially severe during cold decades of the Little Ice Age. Storms were often destructive for the Dutch, shattering ships and breaking through dikes that otherwise defended the coastal Low Countries from the sea. Yet because Dutch warships fared better in storms than their English counterparts, bad weather also offered advantages for the Dutch in a series of 17th-century wars with England. One of those wars ended with a Dutch victory in the same year Backhuysen completed his painting.

Despite overwhelming challenges, much of Dutch society thrived during the Little Ice Age. Paintings by Dutch masters capture the extraordinary affluence of the coastal Dutch Republic in the 17th century. Some of this wealth stemmed from the skill with which the Dutch exploited the opportunities offered by a cooling climate and coped with its most destructive weather.

Yet over the course of the 17th century, a rising share of Dutch wealth came at the expense of the marginalized and colonized. For example, Dutch merchants controlled Europe’s seaborne grain trade. They used that control to sell grain for handsome profits when cold snaps or droughts ruined harvests and worsened food shortages. In subhumid and dry savanna regions across Africa, cooling may have reduced the burden of diseases like malaria and trypanosomiasis, allowing Dutch slavers to work with more ruthless efficiency.

While we should urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions to minimize the eventual magnitude of global warming, we now have little choice but to adapt to a hotter and more extreme climate. We can find inspiration, and perhaps some reassurance, in 17th-century Dutch history and art. But we must also remember the cost of Dutch successes. Climate adaptation must be just. It must reduce inequality, rather than exacerbate it. If it does, artists may yet paint hopeful vistas of our hotter future.

You may also like

Article: Five Artworks About Climate Change

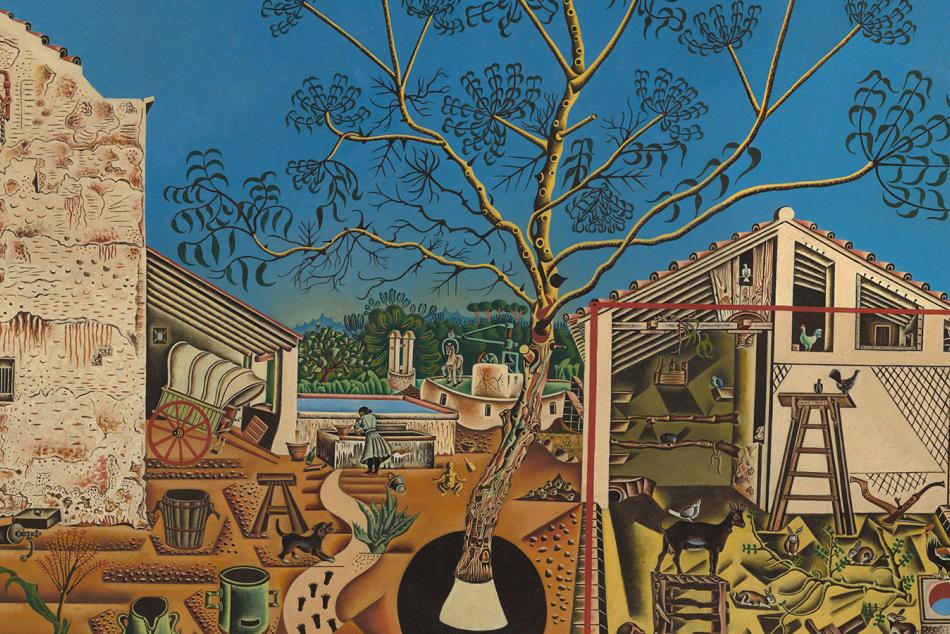

Works by Joan Miró, Ansel Adams, and other artists can inspire a conversation about our impact on the environment.

Article: In Plain Sight: Finding Your First (Art) Love

How can we learn to fall in love with a work of art? From curators who share the works that sparked their lifelong passion for art.