Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer

1640

Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck

Painter, Dutch, 1606/1609 - 1662

With great bravura, this fashionably clad member of the Haarlem civic guard stands with one arm akimbo, staring out at the viewer. His proud bearing, accented by the panache of his shimmering pink satin costume and plumed hat, attests to the great sense of confidence felt by the Dutch at the height of their "golden age."

Andries Stilte, whose family coat of arms decorates the upper corner of this painting, is presented as a standard bearer, or ensign, of the Kloveniers, one of Haarlem’s militia companies. During the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, militia companies served as a civic guard. By 1640, when Verspronck made this portrait, civic guard companies had lost most of their military function. Officers were chosen from Haarlem’s wealthy burghers, who vied for these prestigious appointments. The blue standard and sash serve to identify Stilte’s company and rank, but the rest of his outfit displays his personal taste, his family’s wealth, and his status as a bachelor (Haarlem’s militia regulations stipulated that only unmarried men could serve as ensigns). Stilte commissioned Verspronck to paint him wearing his sumptuous pink costume right before he resigned his rank to marry. As a married militia officer, Stilte would have worn an elegant black outfit.

Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck was one of the foremost portraitists in Haarlem during the mid-seventeenth century. Little is known about his artistic background, although he probably studied first with his artist-father, Cornelis Engelsz (c. 1575–1650). Verspronck may also have trained with Frans Hals (c. 1582/1583–1666). While many seventeenth-century Dutch artists, including Hals, portrayed Dutch militia companies, a life-size portrait of an individual ensign—such as Verspronck's striking likeness of Stilte—is exceedingly rare.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 46

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 104 x 78.5 cm (40 15/16 x 30 7/8 in.)

framed: 137.2 x 111.8 x 8.9 cm (54 x 44 x 3 1/2 in.) -

Accession Number

1998.13.1

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Jacques Goudstikker, Amsterdam), before 1917. Dr. Walter von Pannwitz [1856-1920], Berlin, by 1917;[1] by inheritance to his wife, Catalina von Pannwitz [1876-1959, née Roth], Heemstede; by descent in the Pannwitz family; (Otto Nauman, Ltd., New York); purchased 1988 by Mr. and Mrs. Michal Hornstein, Montreal; (sale, Sotheby's, New York, 30 January 1998, no. 69); purchased through (Bob P. Haboldt & Co., New York) by NGA.

[1] The Pannwitz family lent the painting to the Mauritshuis, The Hague, from 1917 to 1923. Walter von Pannwitz was a Munich lawyer who, with his second wife Catalina Roth, relocated to Berlin in 1910. He acquired an extensive collection of paintings and applied arts in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1917

Loan to display with permanent collection, Mauritshuis, The Hague, 1917-1923.

2000

Face to Face in the Mauritshuis, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague, 2000, no cat.

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2000-2001, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

2007

Dutch Portraits: The Age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals, The National Gallery, London; Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague, 2007-2008, no. 64, repro.

Bibliography

1920

Martin, Wilhelm. Kurzgefasster Katalog der Gemälde- und Skulpturensammlung, Königliche Gemälde Galerie Mauritshuis. The Hague, 1920: 84, no. 753.

1921

Martin, Wilhelm. Alt-holländische Bilder: Sammeln, Bestimmen, Konservieren. Berlin, 1921: 172-173.

1926

Friedländer, Max J. Die Kunstsammlung von Pannwitz. 2 vols. Munich, 1926: 1:11-12, no. 54, pl. 43.

1976

Yapou, Yonna. "Portraiture and Genre in a Painting Restored to Jan Verspronck." Israel Museum News 11 (1976): 41-46, fig. 7.

1979

Ekkart, Rudolf E. O. Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck: leven en werken van een Haarlems portretschilder uit de 17de eeuw. Exh. cat. Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem, 1979: 40, 78, no. 19, repro. 150.

1990

Sutton, Peter C. "Recent Patterns of Public and Private Collecting of Dutch Art." In Great Dutch Paintings from America. Edited by Ben P. J. Broos. Exh. cat. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Zwolle, 1990: 118, fig. 23.

1995

Otto Naumann Ltd. Inaugural exhibition of old master paintings. Exh. cat. Otto Naumann Ltd., New York, 1995: 140, color repro.

2000

National Gallery of Art. Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2000: 34-35, color repro.

Weller, Dennis P. Like Father, Like Son? Portraits by Frans Hals and Jan Hals. Exh. cat. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, 2000: fig. 6, color repro.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 212-213, no. 170, color repro.

2007

Ekkart, Rudolf E.O., and Quentin Buvelot. Dutch portraits: the age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals. Translated by Beverly Jackson. Exh. cat. National Gallery, London; Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. London, 2007: 220-221, no. 64, repro.

2008

Buvelot, Quentin. "El retrato holandés." Numen 2 (2008): 14, 25, repro.

2009

Ekkart, Rudolf E.O.. Johannes Verspronck and the Girl in Blue. Amsterdam, 2009: 20, 22, 58, color fig. 14.

2012

Tummers, Anna. The Eye of the Connoisseur: Authenticating Paintings by Rembrandt and His Contemporaries. Amsterdam, 2012: 244, 245, color fig. 154.

2014

Wheelock, Arthur K, Jr. "The Evolution of the Dutch Painting Collection." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 50 (Spring 2014): 2-19, repro.

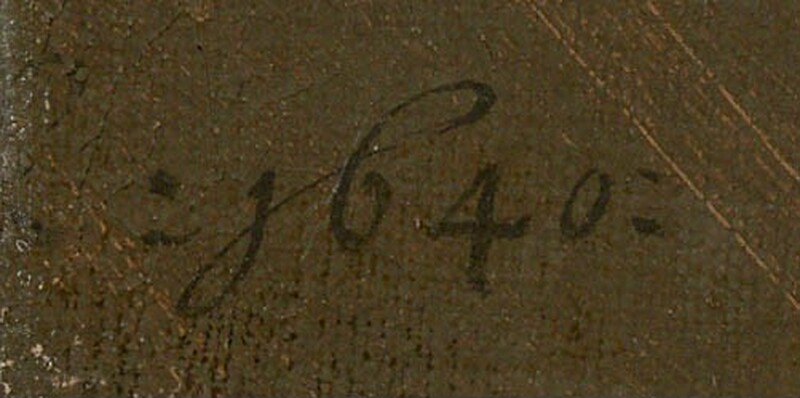

Inscriptions

lower left: :1640:

Wikidata ID

Q20177165