Language

On this Page:

“Art in America has always belonged to the people and has never been the property of an academy or a class. . . . The Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration is a practical relief project which also emphasizes the best tradition of the democratic spirit. The WPA artist, in rendering his own impression of things, speaks also for the spirit of his fellow countrymen everywhere. I think the WPA artist exemplifies with great force the essential place which the arts have in a democratic society such as ours.”

—Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Radio Dedication of the Museum of Modern Art, New York City,” May 10, 1939.

Overview

Does art “work” or have a purpose? How?

Is making art a form of work? Make your argument for why or why not.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt stated that art in America has never been the sole province of a select group or class of people. Do you agree or disagree?

Define what you think Roosevelt meant by “the democratic spirit.” How do you think art can represent democratic values?

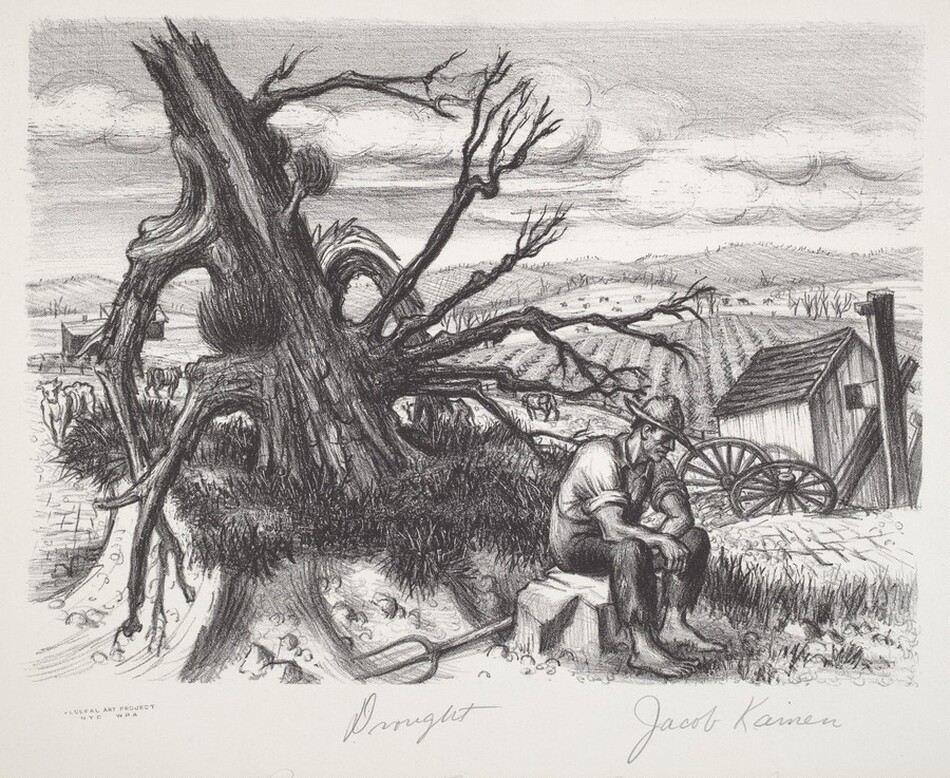

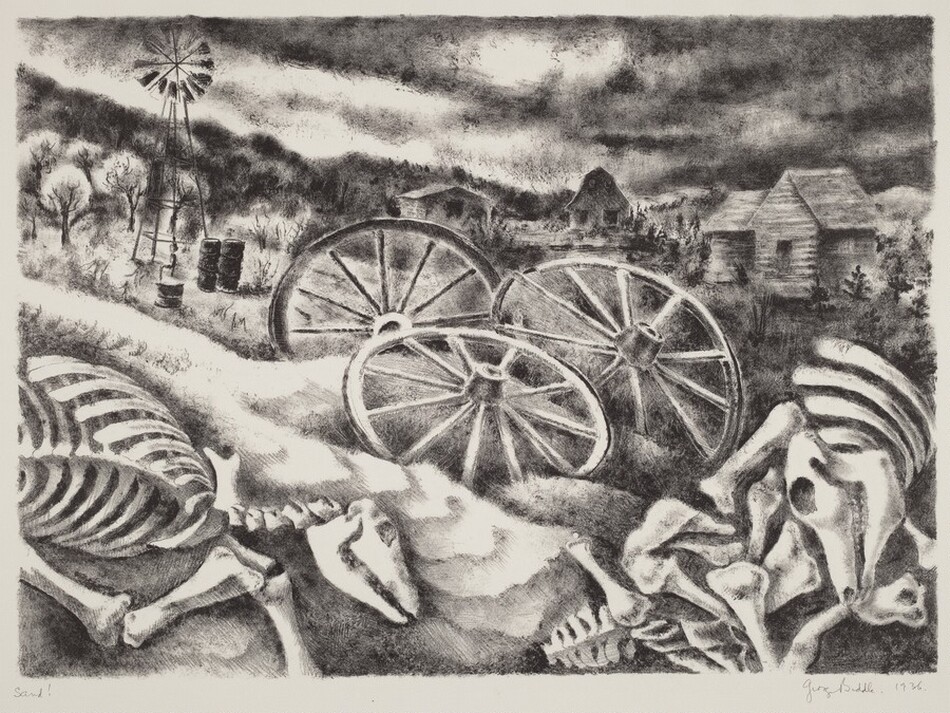

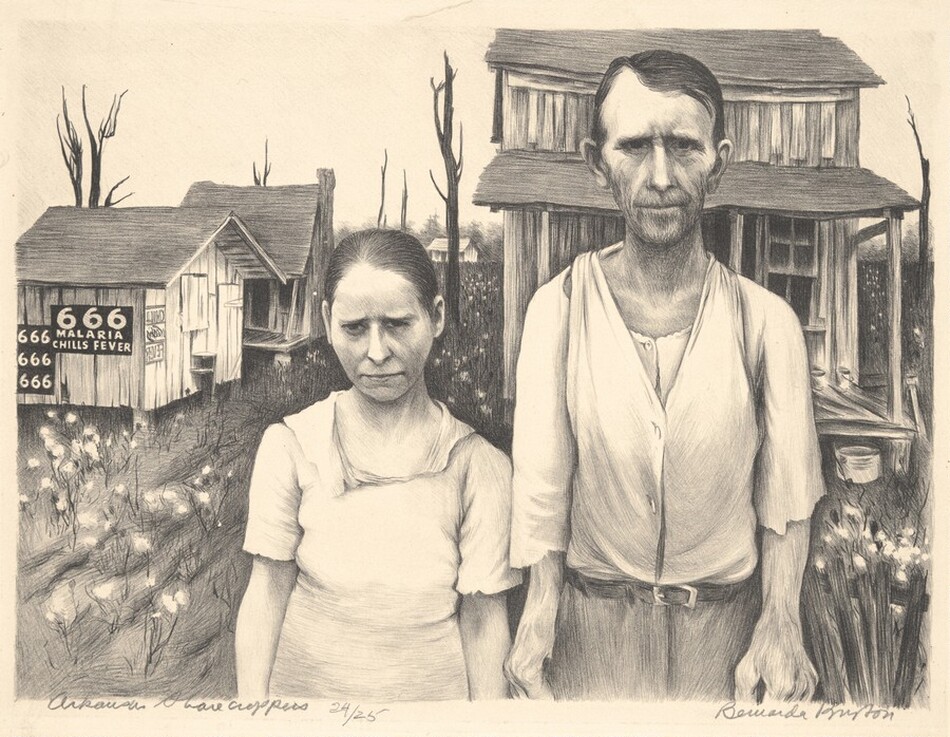

The Great Depression spanned the years 1929 to about 1939, a period of economic crisis in the United States and around the world. High stock prices out of sync with production and consumer demand for goods caused a market bubble that burst on October 24, 1929, the famous “Black Thursday” stock market crash. The severity of the market contraction affected Americans across the country. The most visible effects included widespread unemployment, homelessness, and a marked decrease in Americans’ standard of living. In addition, a severe drought produced the Dust Bowl—a series of damaging dust storms. This environmental disaster ruined many farmers during a period when the economy was largely agricultural.

In office at the time of the crash, President Herbert Hoover (term 1929–1933) was unable to stop the free fall of the American economy. His successor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was elected president in a landslide in 1933 with campaign promises to fix the economy. Roosevelt acted quickly to create jobs and stimulate the economy through the creation of what he called “a New Deal for the forgotten man”—a program for people without resources to support themselves or their families. The New Deal was formalized as the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA), an umbrella agency for the many programs created to help Americans during the Depression, including infrastructure projects, jobs programs, and social services.

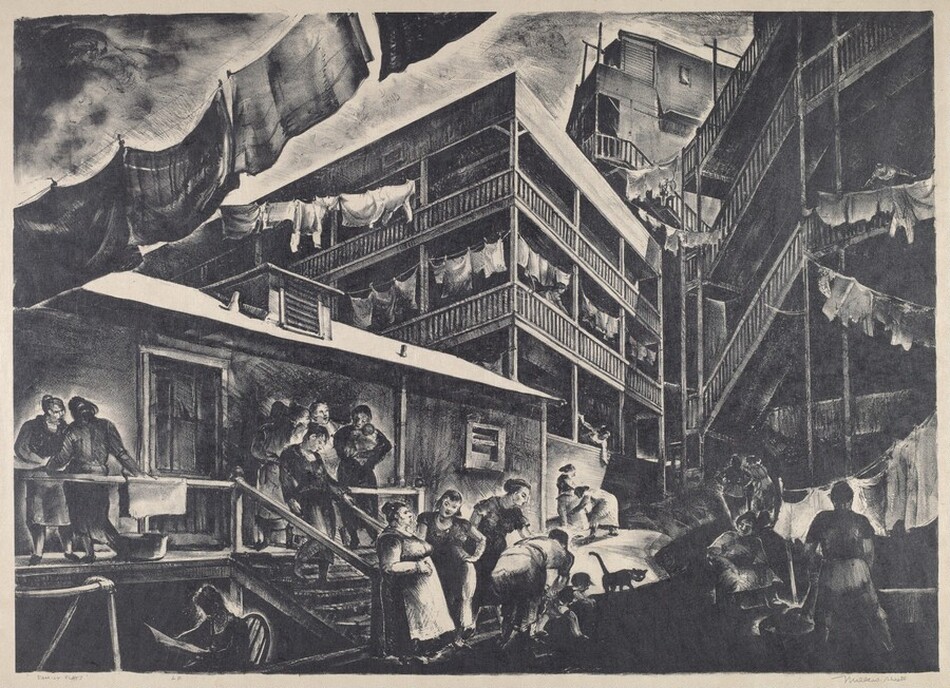

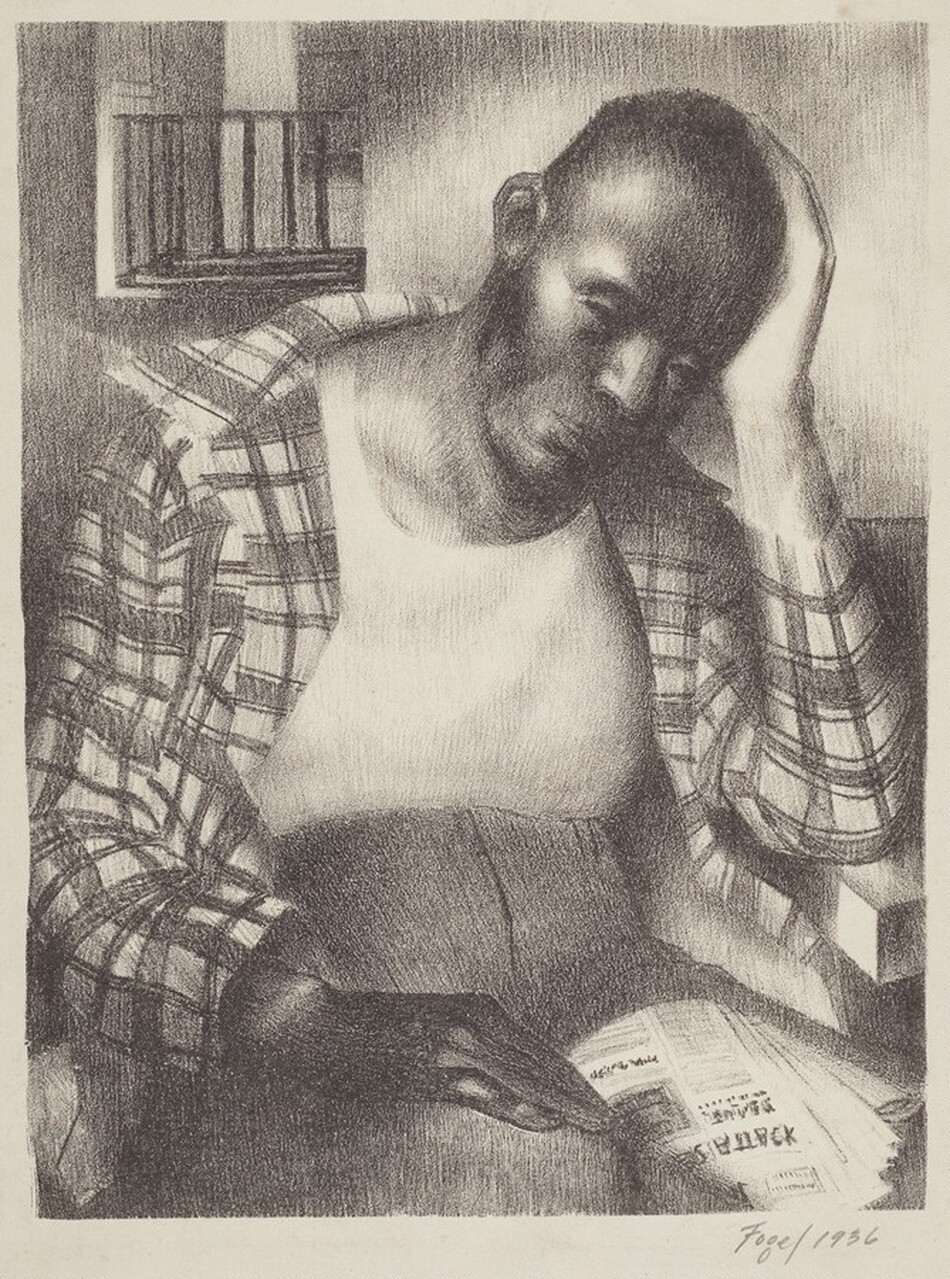

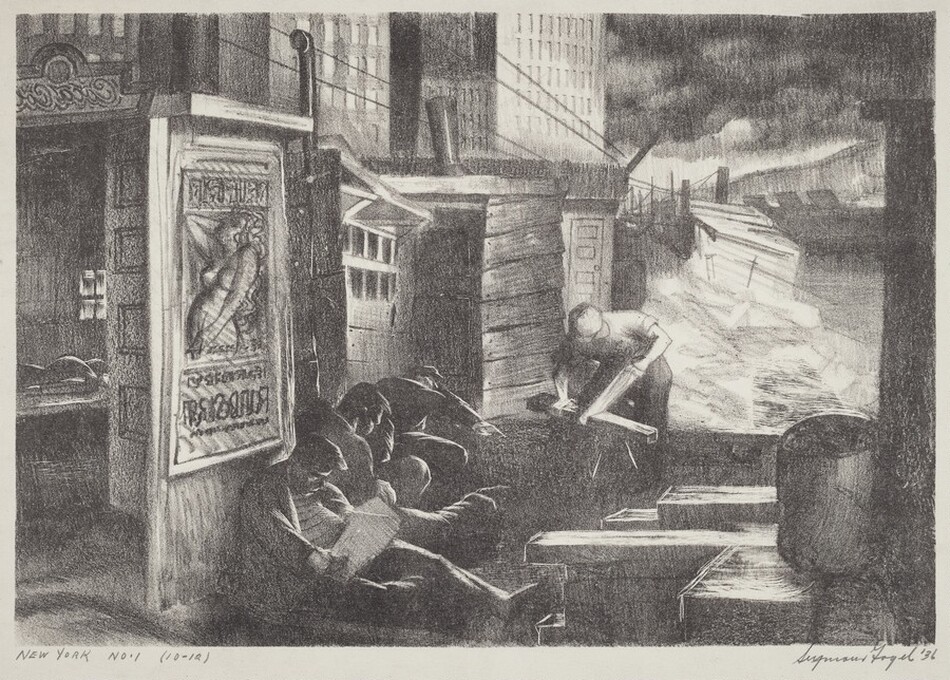

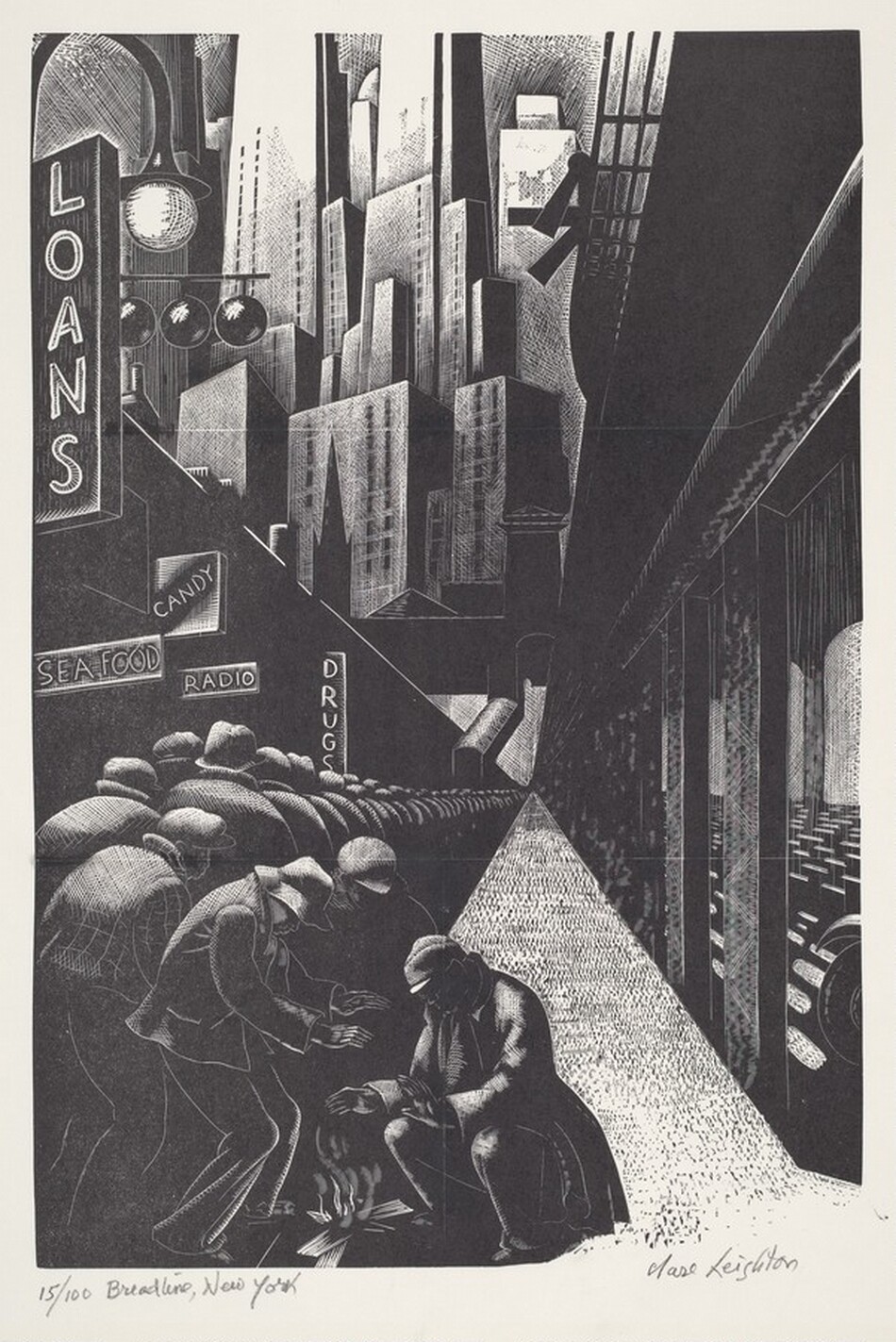

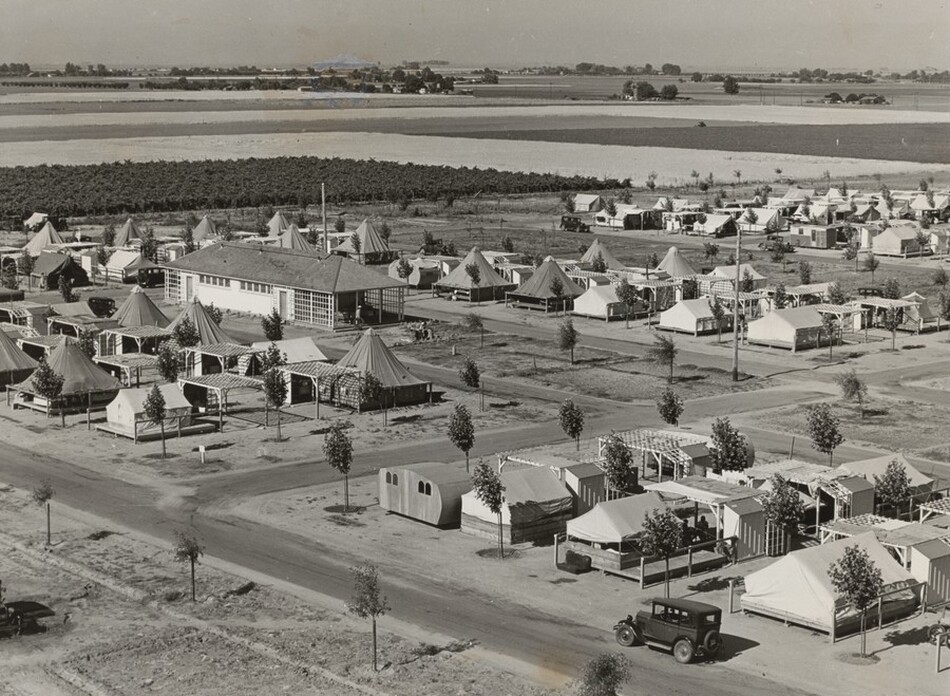

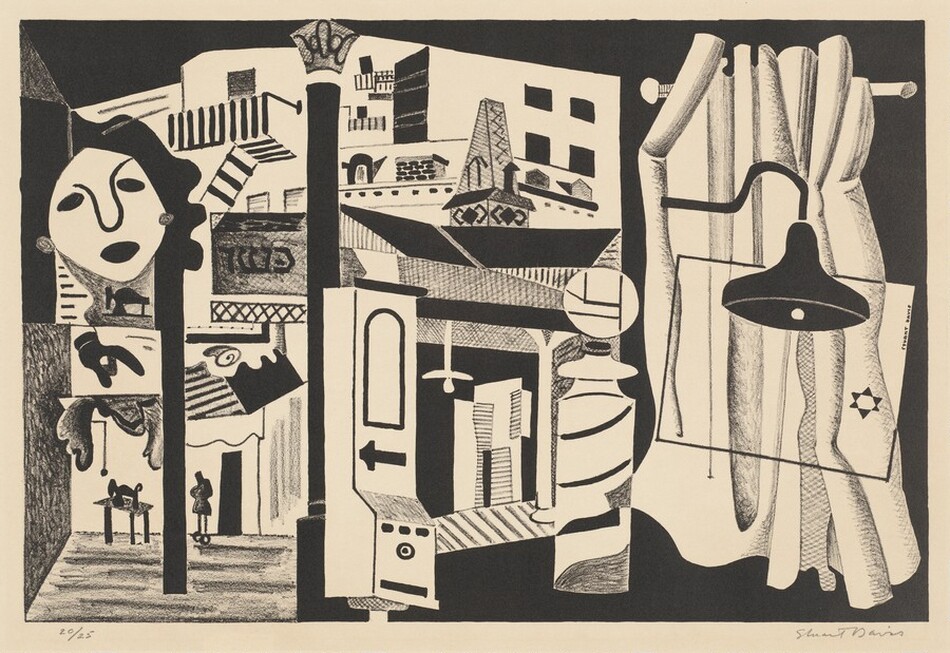

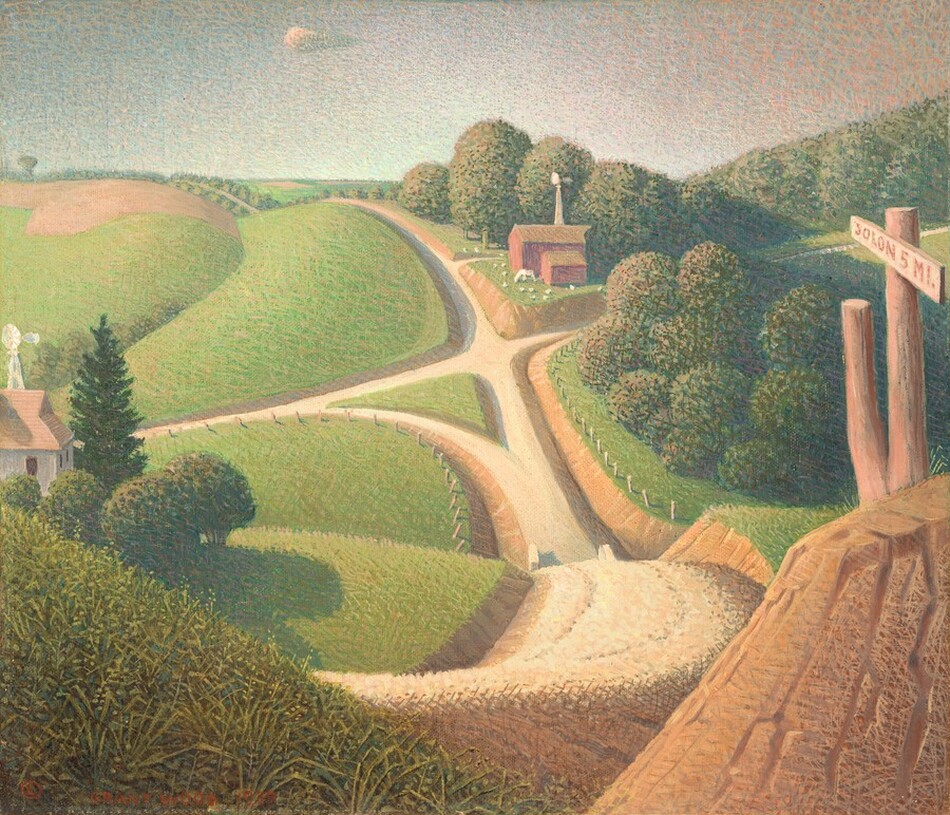

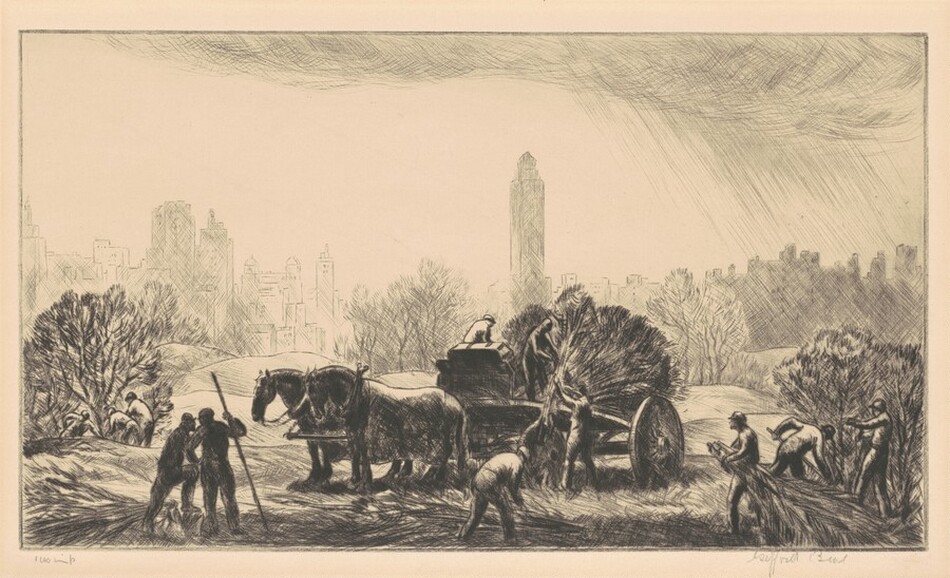

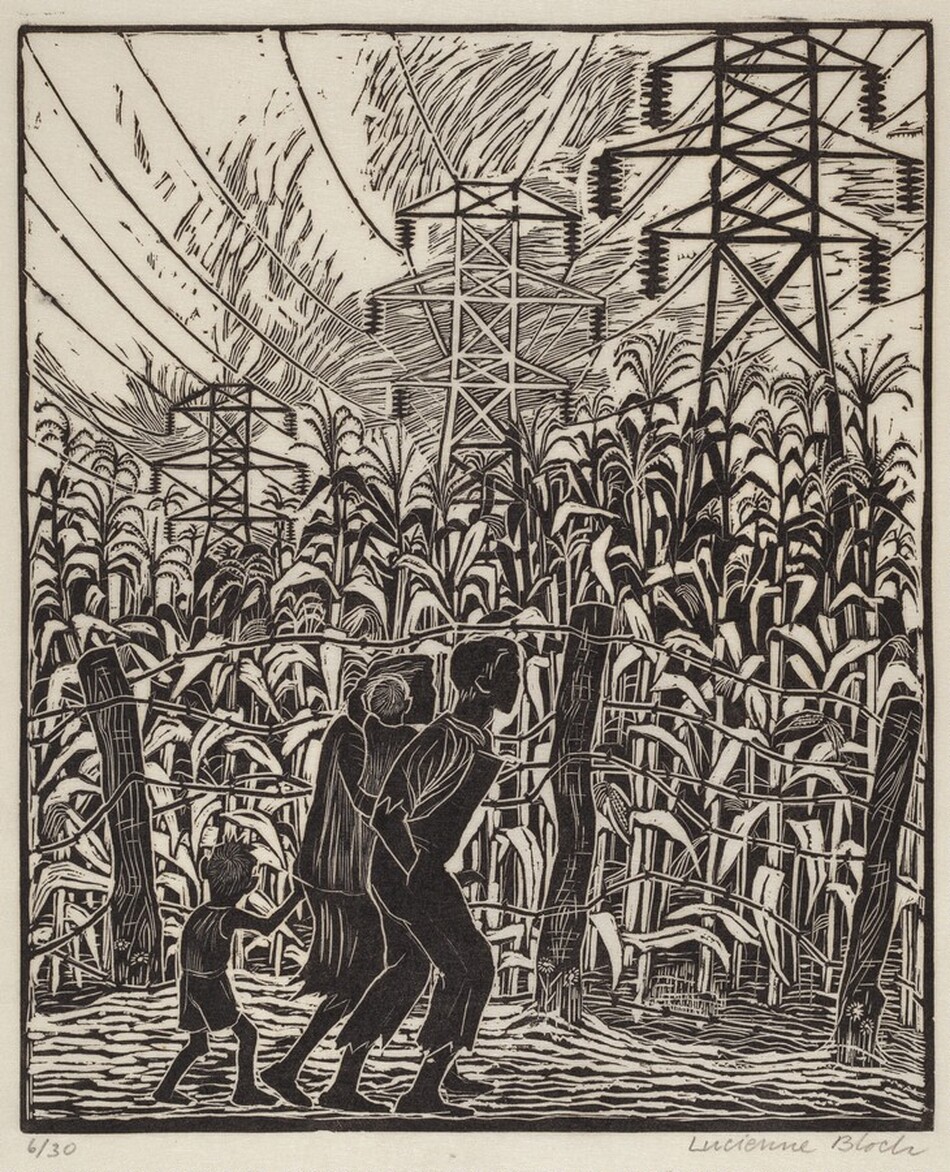

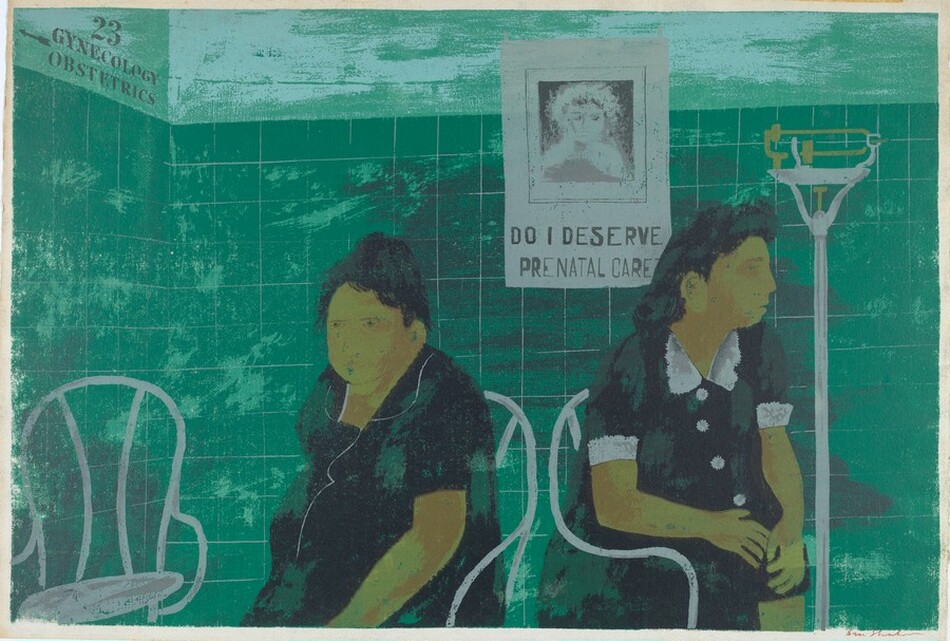

Through the WPA, artists also participated in government employment programs in every state and county in the nation. In 1935, Roosevelt created the Federal Art Project (FAP) as the agency that would administer artist employment projects, federal art commissions, and community art centers. Roosevelt saw the arts and access to them as fundamental to American life and democracy. He believed the arts fostered resilience and pride in American culture and history. The art created under the WPA offers a unique snapshot of the country, its people, and art practices of the period. There were no government-mandated requirements about the subject of the art or its style. The expectation was that the art would relate to the times, reflect the place in which it was created, and be accessible to a broad public.

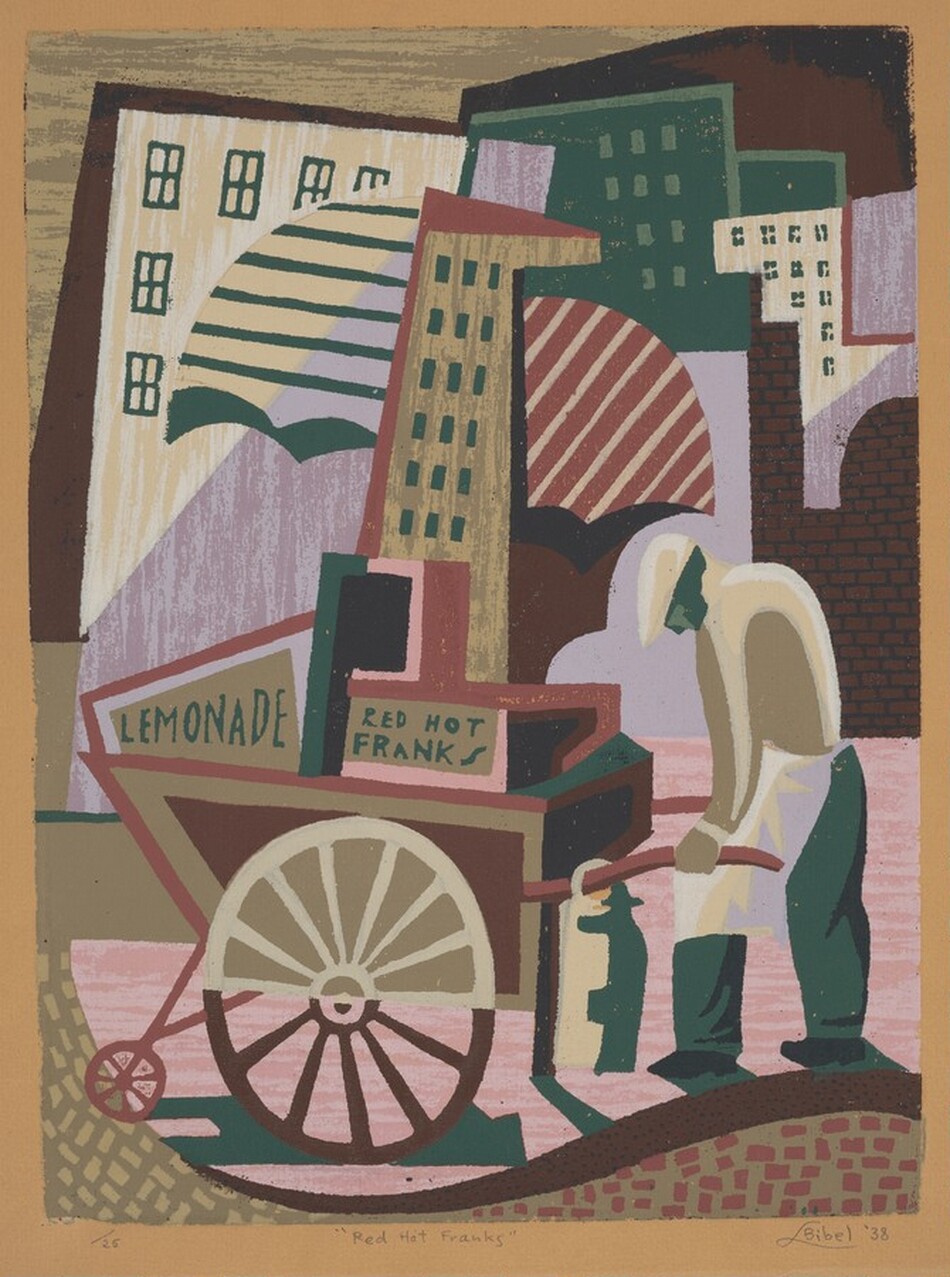

Artists working in the FAP and for other WPA agencies created prints, easel paintings, drawings, and photographs. Public murals were painted for display in post offices, schools, airports, housing developments, and other government buildings. Community art centers hosted exhibitions of work made by artists employed in government programs and offered hands-on workshops, led by artists, for everyone. Illustrators made detailed drawings that cataloged the physical culture and artifacts of American daily life—clothing, tools, household items. The WPA intentionally seeded arts programs and supported artists outside of urban centers. In so doing, it introduced the arts to a much more diverse swath of Americans, many of whom had previously never seen an original painting or work of art, had not met a professional artist, nor experimented with art making.

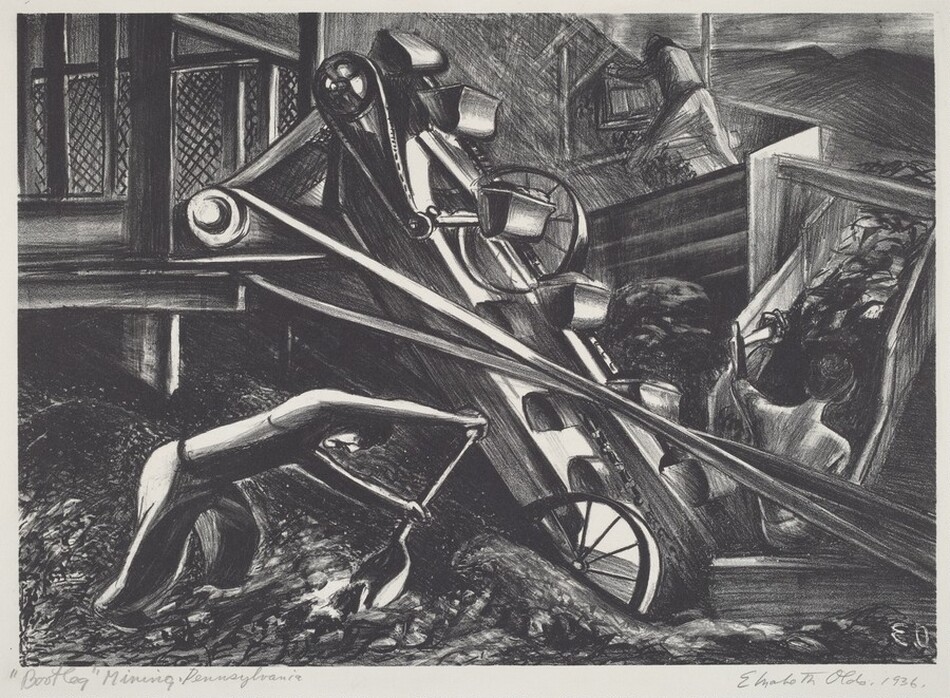

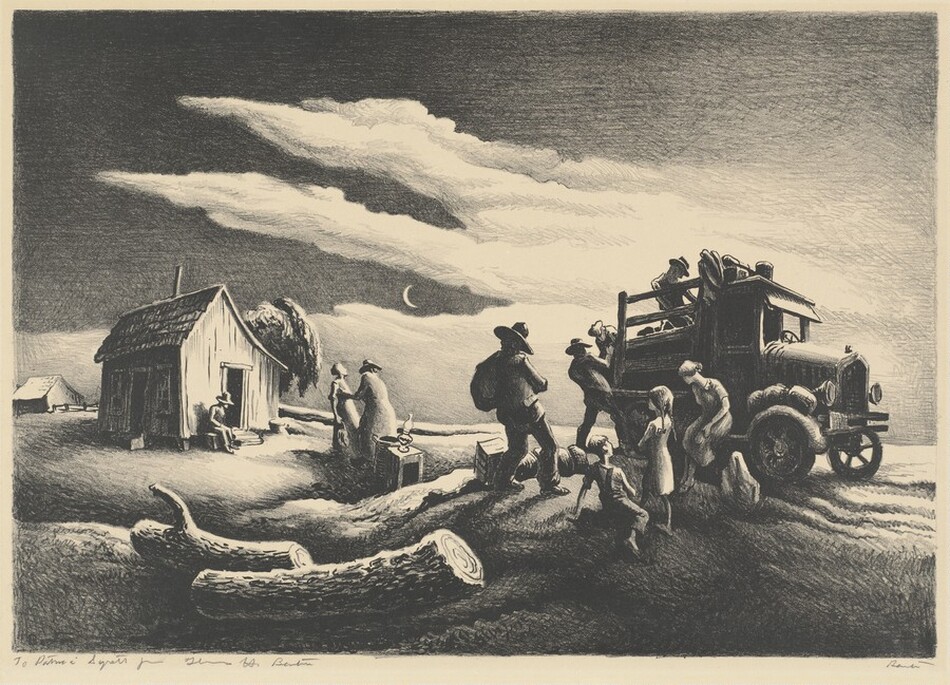

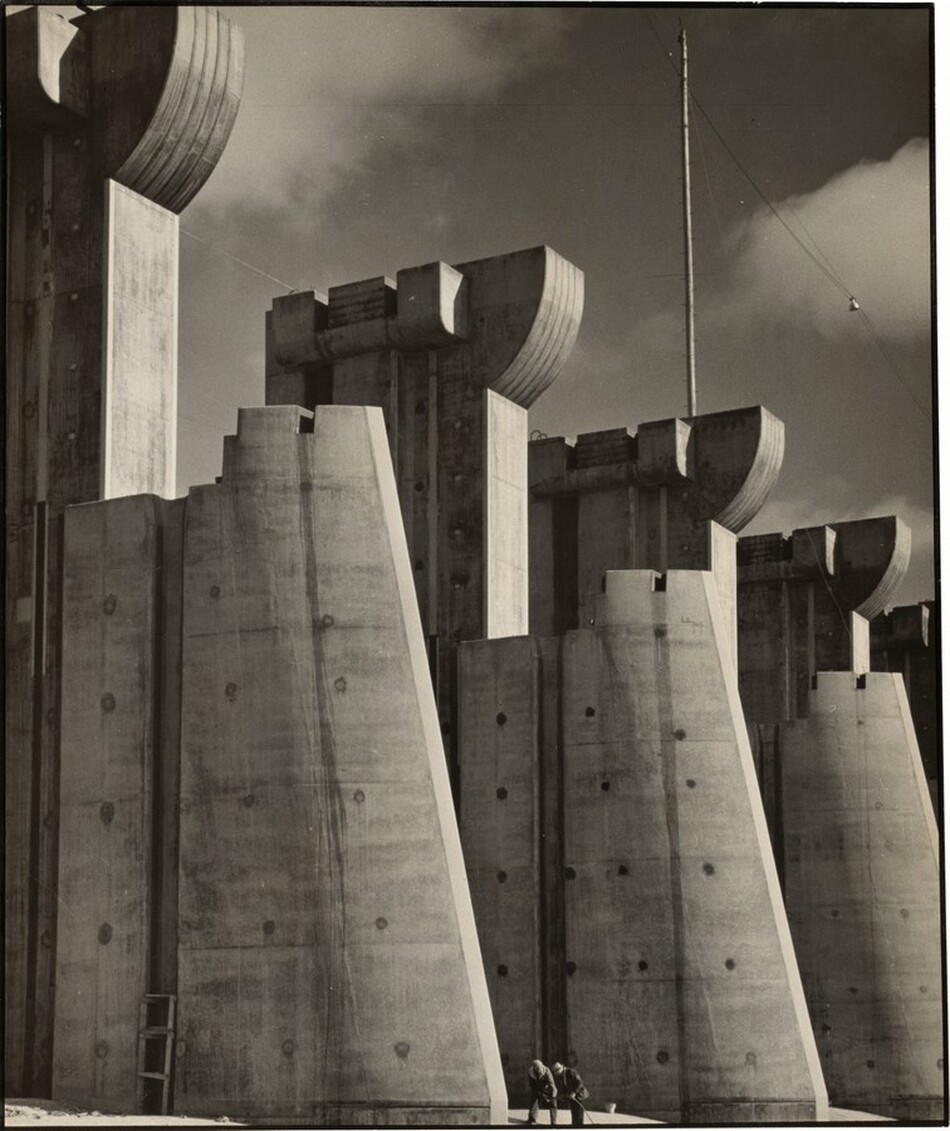

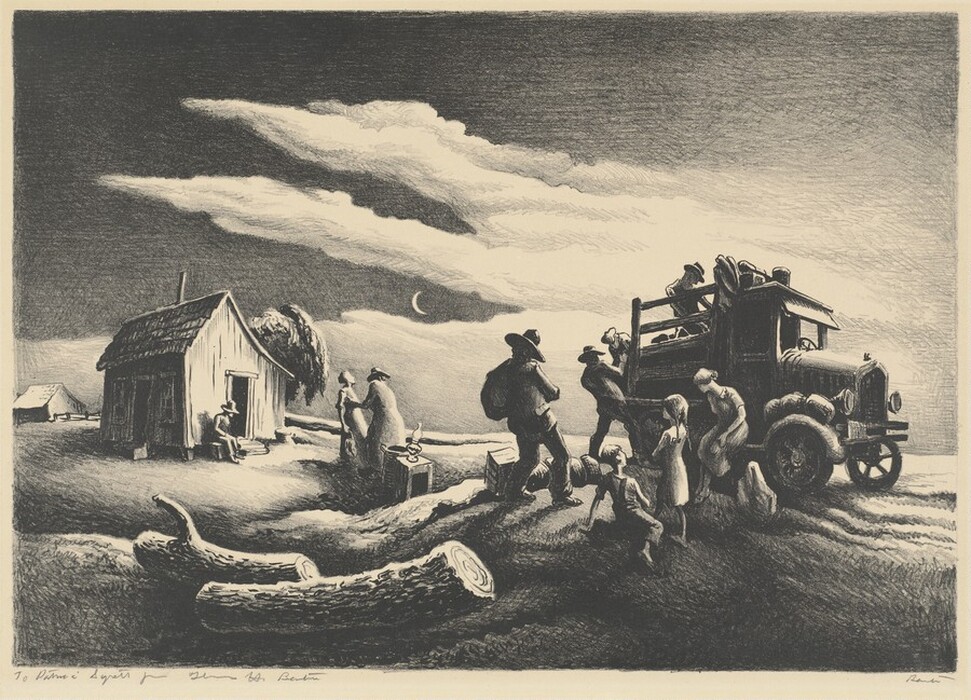

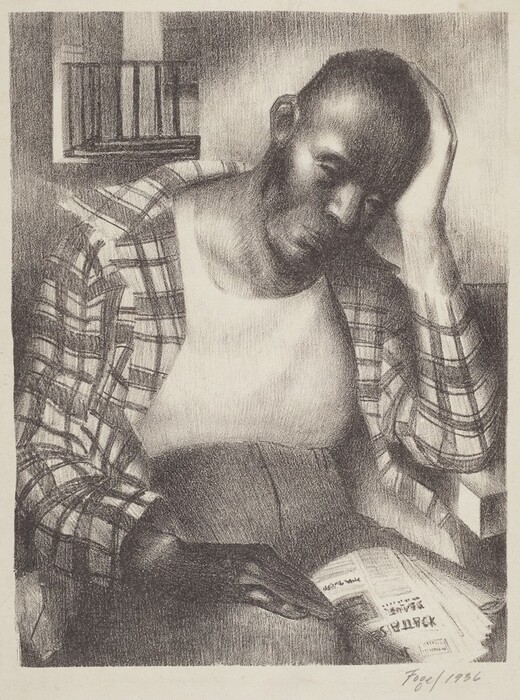

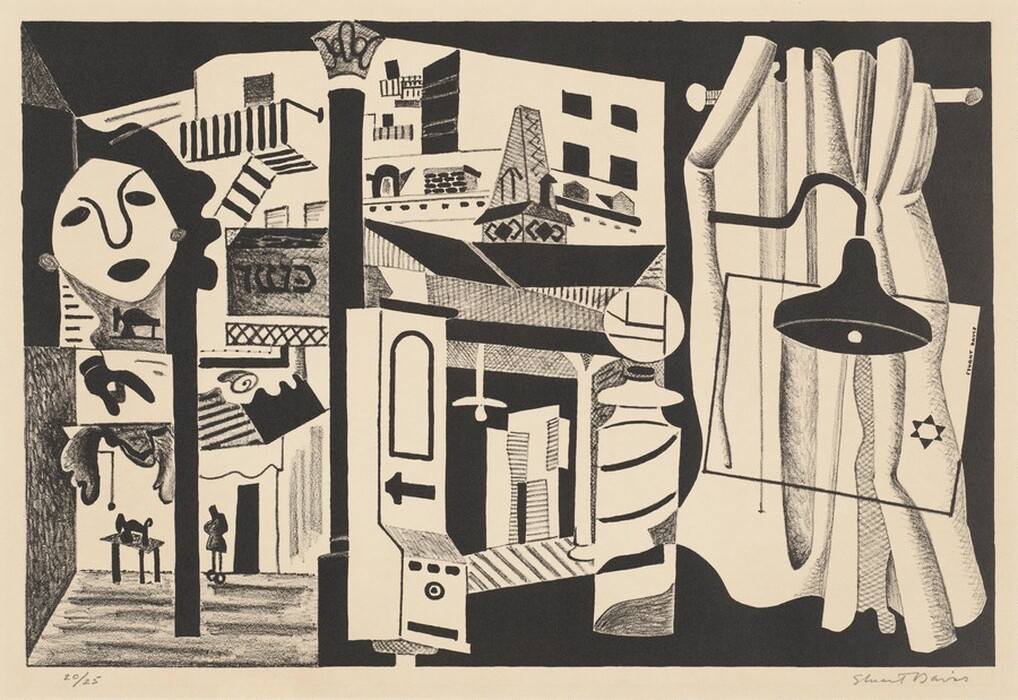

The art produced through government programs pictured both the hardship of the period and a vision of a better America. Breadlines, homelessness, and farms reduced to sand were common subjects. The successes of WPA programs were depicted and documented, too: triumphs such as the construction of vast dams to provide flood control for farmlands and generate hydroelectric power, the expansion of the electrical power grid across the country, and conservation and agriculture programs to restore productivity to areas of the country swept by dust and wind storms. Artists created idealized visions for the future and experimented with abstraction in response to the changing world around them. Under Roosevelt’s government programs, artists found meaningful work in making art for ordinary Americans and publicizing the WPA’s accomplishments. The WPA-era art programs reflected a trend toward the democratization of the arts in the United States and a striving to develop a uniquely American and broadly inclusive cultural life.

The WPA’s Federal Art Project ended in 1943. The United States had entered World War II, and war-related production boosted the economy at home and spurred job creation. The FAP also came under question politically, as some groups cast it as a producer of propaganda that curtailed artists’ freedom of expression.

The National Gallery of Art collection contains many examples of works of art from this period of history. The art offers a window through which to explore the social conditions of the Depression, the mainstreaming of art and birth of “public art,” and the opening of government employment to women and African Americans.

Selected Works

Activity: Respond and Relate

- View the images in the set one by one. Ask students to look and list what they observe, including people, objects, settings, and the style of the art. Using that information as a guide, ask them to interpret the meaning or message of selected images and the mood or feeling the images convey.

- Next, try to categorize and group the types of images in the set. Ask students to develop their own categories based upon what they see. Then, relate the categories they identify with real-life circumstances and facts of the Depression, such as the following:

- unemployment or homelessness figures;

- facts about the drought/Dust Bowl and its ecology;

- human migrations and displacements;

- information about different job sectors;

- WPA-era public facilities built in your community (e.g., bridges, schools, post offices, roads); and

- cultural phenomena not supported by the WPA that proceeded in spite of the Depression (e.g., the Harlem Renaissance).

- Are there images that students cannot relate to their present-day lives or do not understand? Why? Explore the historical context of those images to arrive at an understanding of what is pictured and why the artist may have chosen to create that image.

Activity: Political Expressions and Social Justice

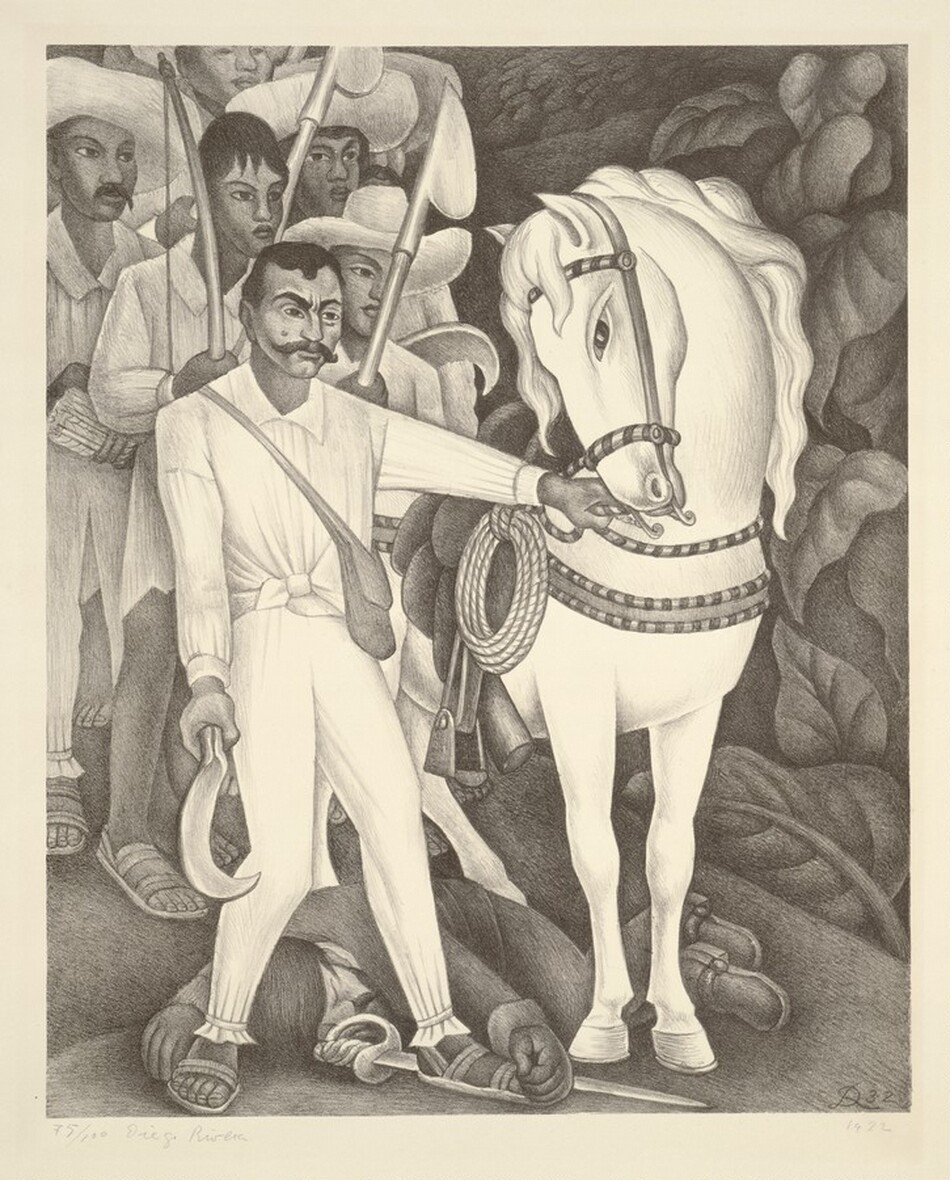

"For the first time in the history of monumental painting, Mexican muralism ended the focus on gods, kings and heads of state and made the masses the hero of monumental art."--Diego Rivera

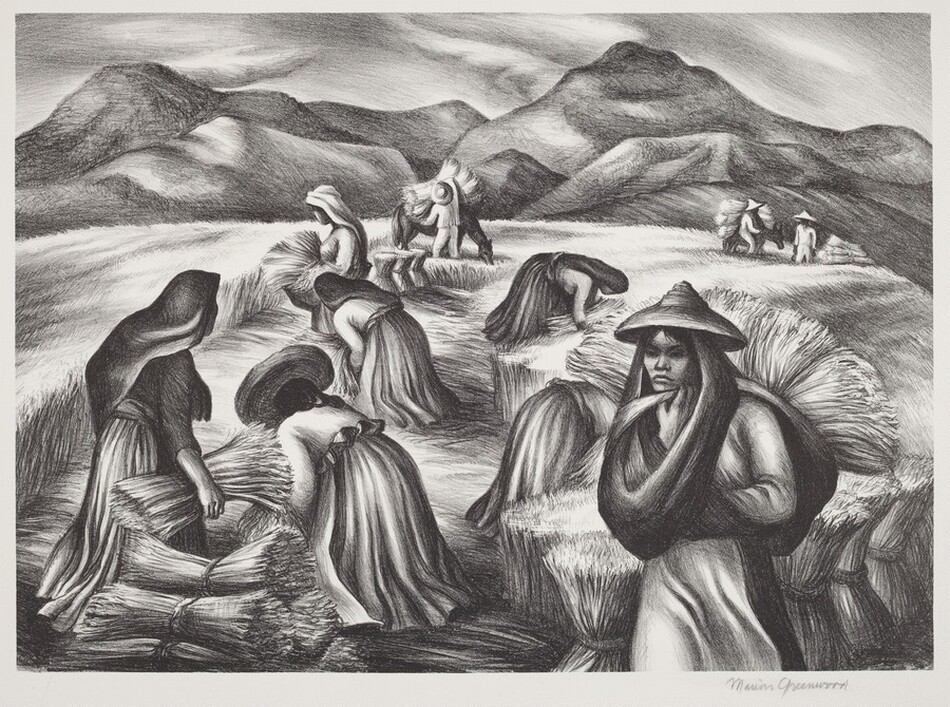

In this quote, Rivera is referring to large-scale murals he and other artists were commissioned to paint by the Mexican government focused on the lives of ordinary people, rather than the elite. Rivera and a group of Mexican muralists greatly influenced the creation of US government art programs during the Depression, as well as the work of many WPA-era artists who became well-known in later years, such as Jackson Pollock.

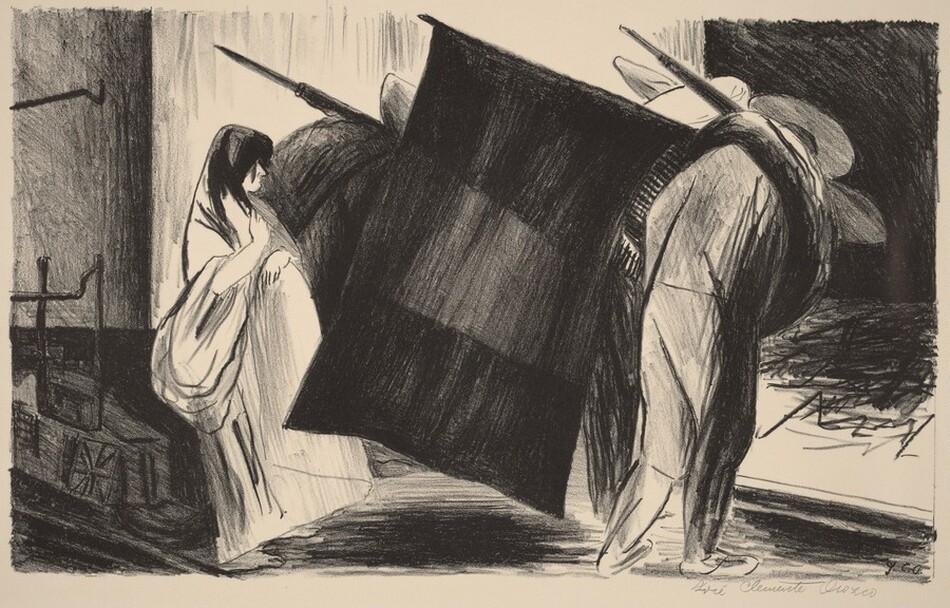

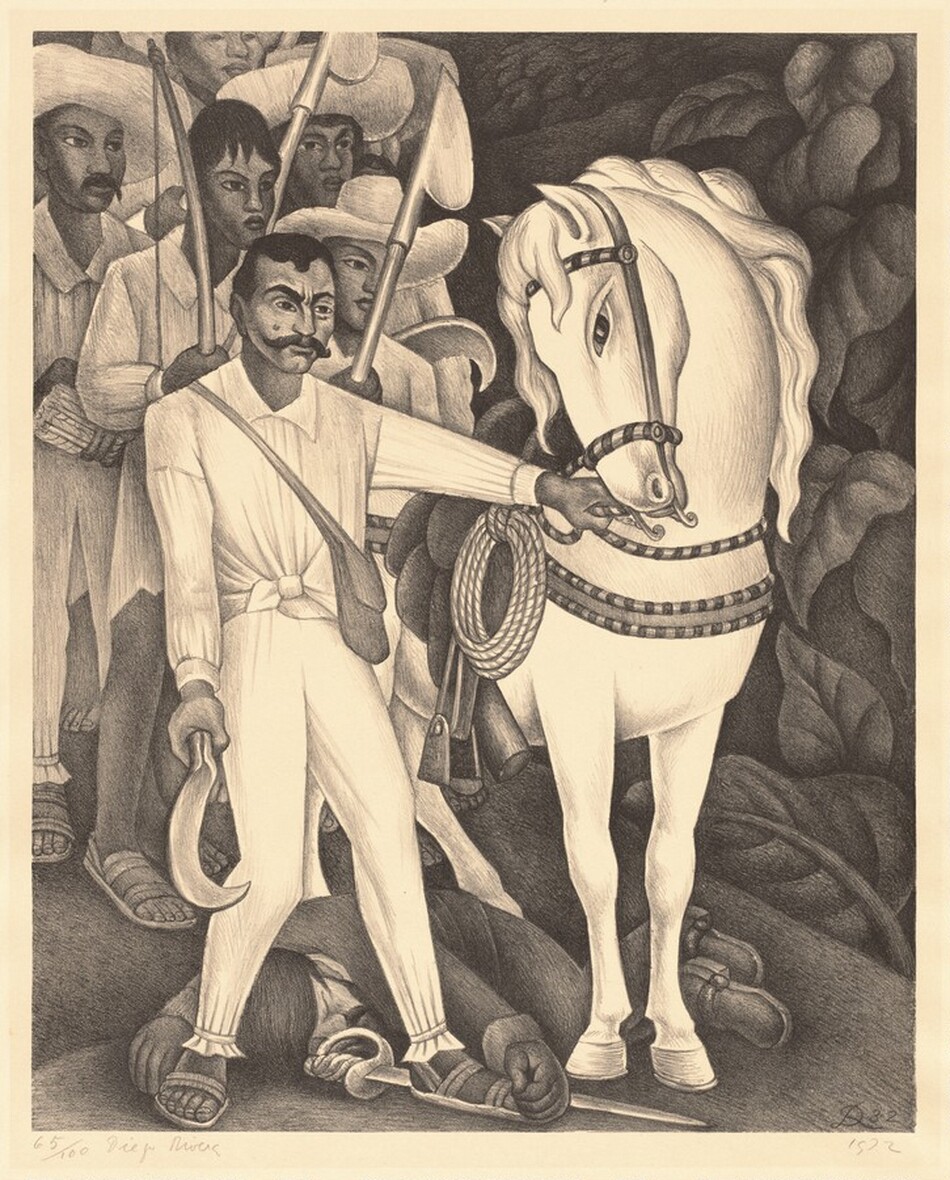

The Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) overthrew a dictatorship favoring the elite class, ushering in an era in which workers and farmers gained political empowerment. The new government, seeking to recognize the shifts in society and stoke pride in Mexican heritage, hired artists to represent the history and people of Mexico. Key among those artists were Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. They looked to the country’s pre-Columbian history for sources of inspiration, as well as to the heroes of the Mexican Revolution such as Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. Zapata is pictured in this work created by Rivera (based upon a painting at the Museum of Modern Art).

The art of Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros offered a new model: art that recognized and gave dignity to the lives and concerns of ordinary people. The artists became internationally renowned for their innovative and distinctive work. They spent time in the United States completing commissions and interpreting US industry and history, including Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts and Orozco’s The Epic of American Civilization at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College.

Compare Diego Rivera, Viva Zapata, 1932, with José Clemente Orozco, Flag (Bandera), 1928.

- List all the details you notice in each image. What has the artist chosen to depict? How has he depicted it?

- Is Zapata, the hero of the Mexican people, the central figure in Viva Zapata? How does Rivera communicate this?

- Zapata holds a scythe used for cutting sugarcane. Another figure lies at his feet, while others look on from the background. What has just happened? Do you think the scene is real or symbolic? What about the figures behind Zapata? What are they gazing at? Who are the people depicted? Describe how they are depicted using as many details as you can.

- Compare the two images and the subjects they depict. How are they related? How are they different?

- Why might Rivera’s and Orozco’s images have been of interest to North American artists during the Great Depression? What parallels do you see between the Mexican mural program and the Federal Art Project?

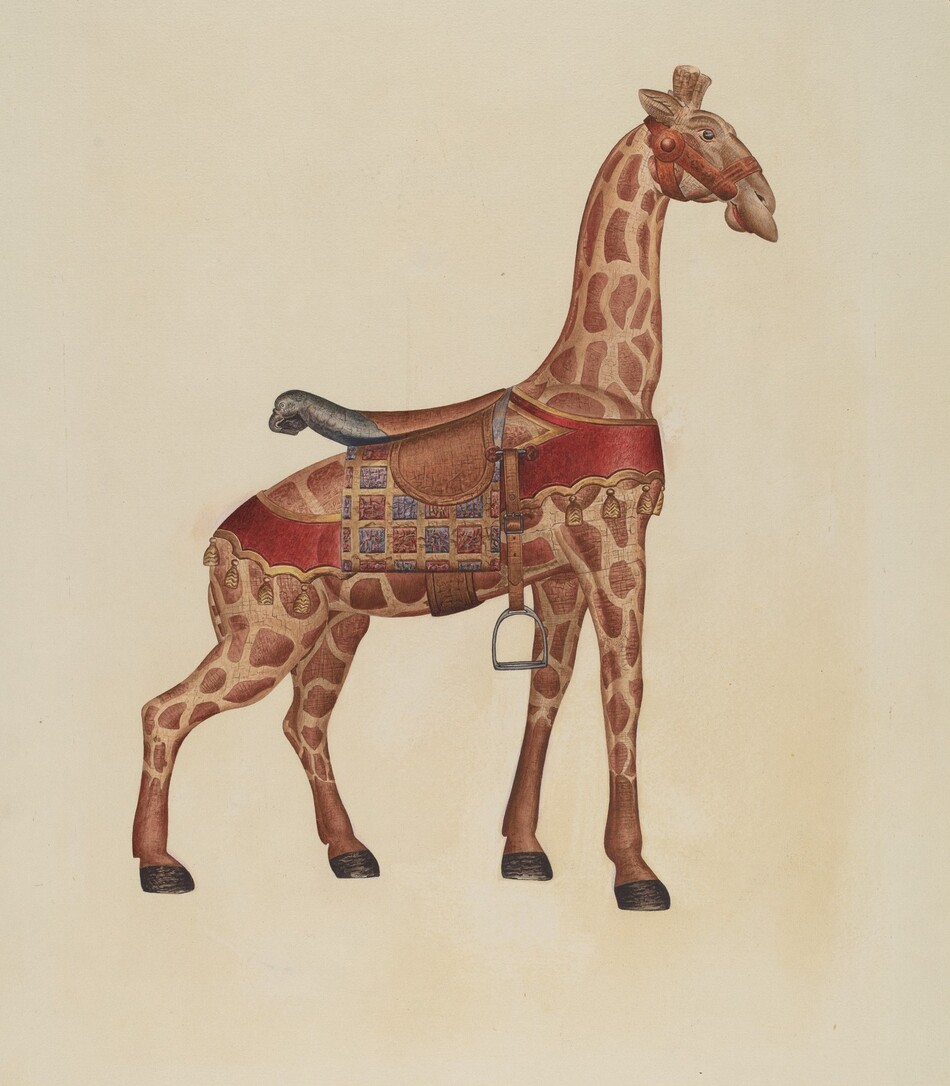

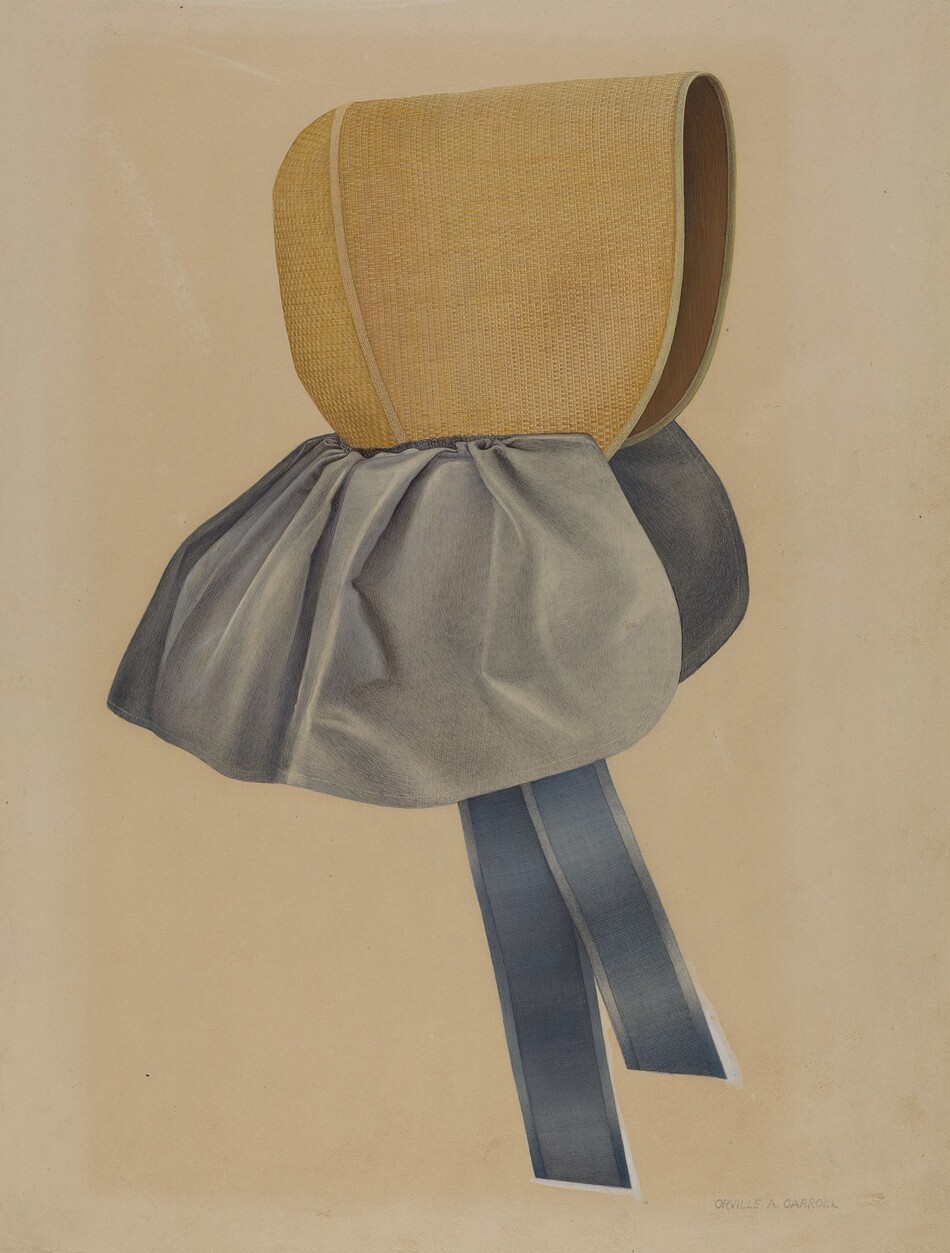

Activity: The Art of Everyday

“A nation’s resources in visual arts are not confined to painting and sculpture and printmaking. They include all the arts of design which express the daily life of a people and which bring order, design, and harmony into an environment which their society creates.” —Holger Cahill, Director, Federal Art Project, 1935–1943

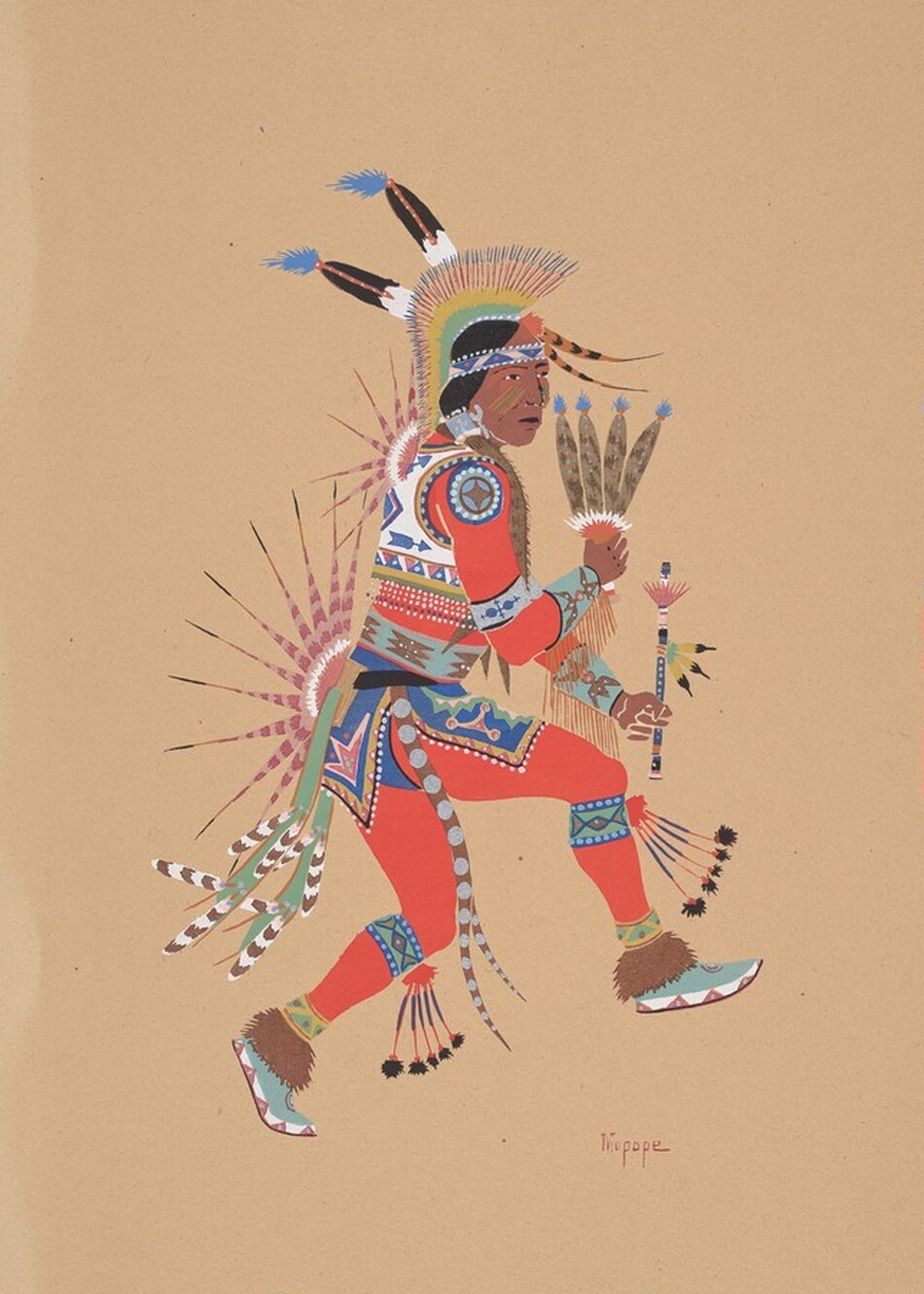

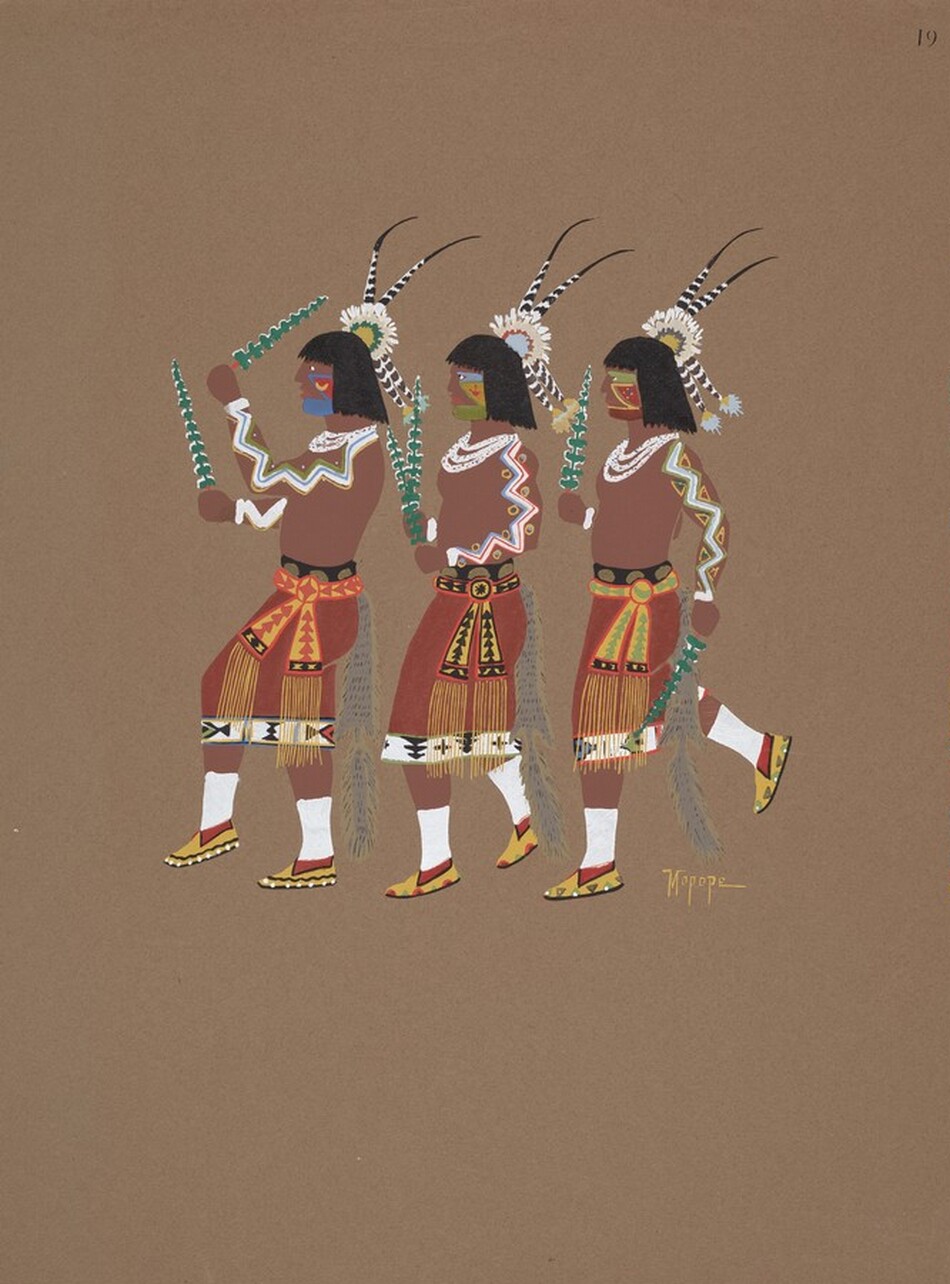

Another WPA program that employed artists was the Index of American Design (IAD). The IAD was a project to document the history of American arts and crafts from colonial times until about 1890. The project helped foster pride in American vernacular (everyday) culture and craftsmanship. It celebrated regional strengths, such as Shaker materials in the Northeast and Kentucky, Native American arts of the Southwest, and German Pennsylvania folk art. The documentation took the form of highly detailed drawings: everything from farming implements, carriages, cooking tools, and furniture to clothing, toys, and musical instruments. Over 400 artists working in 36 states were employed in the IAD. The National Gallery of Art holds about 18,000 of the original drawings made for this project.

- Ask students to draw an everyday object that they use at home or in school in the realistic style of the IAD.

- Display the resulting drawings in an exhibition in the classroom. (The IAD drawings may have once been displayed in a community art center.) When displaying the drawings:

- Group them by category of use (e.g., personal [clothing, jewelry, electronic devices], household, recreation).

- Discuss students’ relationships to their objects. How do they use them? Has the form of the object changed over time?

- Discuss the physical qualities of the object: how it might have been made, where, and by whom. Is it pleasing to use?

How many items are made in the United States?

- Review some examples from the IAD and try to locate objects and categories of objects that no longer exist today.

- Ask students to research what they were used for, where, or how. What objects might they include in such an Index today?

- Are there objects pictured in the IAD that relate to a particular tradition, craft, or style that is local to your community?

Activity: WPA-Era Art in Your Community

The Federal Art Project operated in 48 states. Some 200,000 works of visual art were created, which included murals, prints, posters, photographs, paintings, and drawings. Each state administered its own federally funded art programs.

Use a search engine to locate WPA-era murals in your community. Approximately 2,500 murals were created in all 48 states in existence at the time. (If you live in Alaska or Hawaii, choose a place you are interested in or where family or friends live.)

- If the artwork is publicly accessible and on display (such as a mural in a post office, library, university, or other public building), ask a group of students to research it and then offer a public talk to the class and friends. Be sure to obtain permission from the venue.

- If you locate images of WPA-era murals online, download a high-quality image, or ask a librarian to assist you in finding resources.

- As students study the murals, ask them to respond to the following questions:

- How does the work of art reflect aspects of your community or its history?

- Are there scenes or elements depicted that are no longer true or valid today?

- Who was the artist? Research his or her background and life story.

- Describe the style of the art. Is it realistic or stylized in some way? How do you think its style contributes to its meaning?

Additional Resources

Final Report on the WPA Program, 1935–43 (Washington, DC, [1947])

The Living New Deal: New Deal Inclusion

George Biddle, “An Art Renascence Under Federal Patronage,” Scribner’s, March 1934, 428–431.

Catlin's Indian Cartoons, The Univeristy of California

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Address at the Dedication of the National Gallery of Art,” March 17, 1941

John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York, c. 1934)

Francis O’Connor, Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project (New York, 1975)

You may also like

Educational Resource: People and the Environment

The US national park system exists in part because of artists.

Educational Resource: Manifest Destiny and the West

When you think about the US West, what images and stories come to mind?