Educational Resources

Plan a field trip or bring art into your classroom. Find lesson ideas, teaching resources, or professional development opportunities for yourself.

Filter Results

Filter Results

Loading Results

More resources

Join as an Affiliate

Large organizations and broadcast stations can become affiliates for expanded access to free resources.

Art Around the Corner

Art Around the Corner is a set of programs that partners the National Gallery of Art with D.C-area Title I elementary schools.

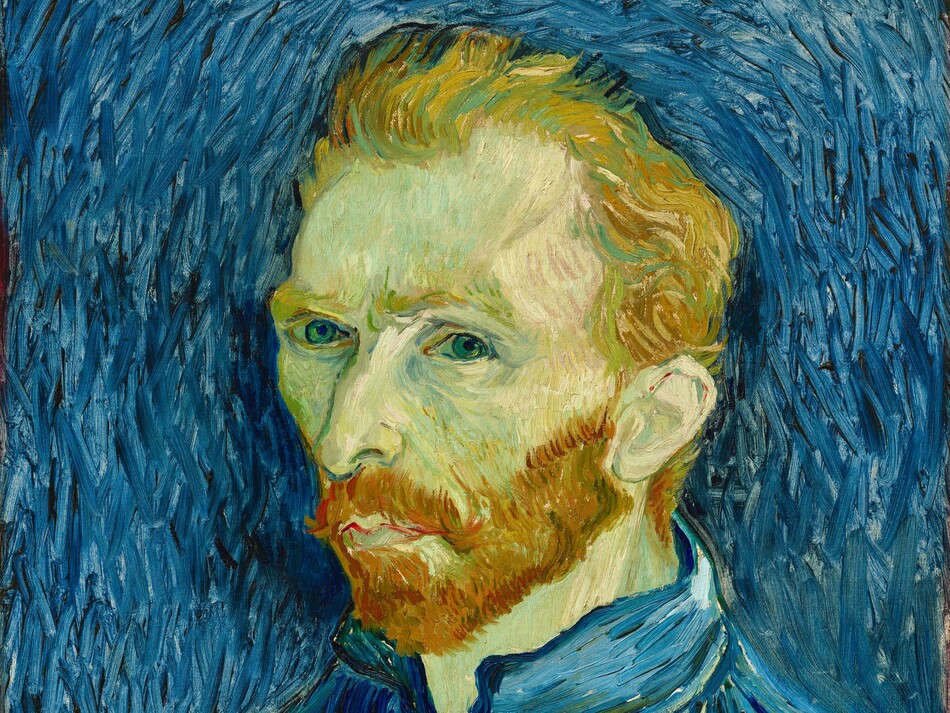

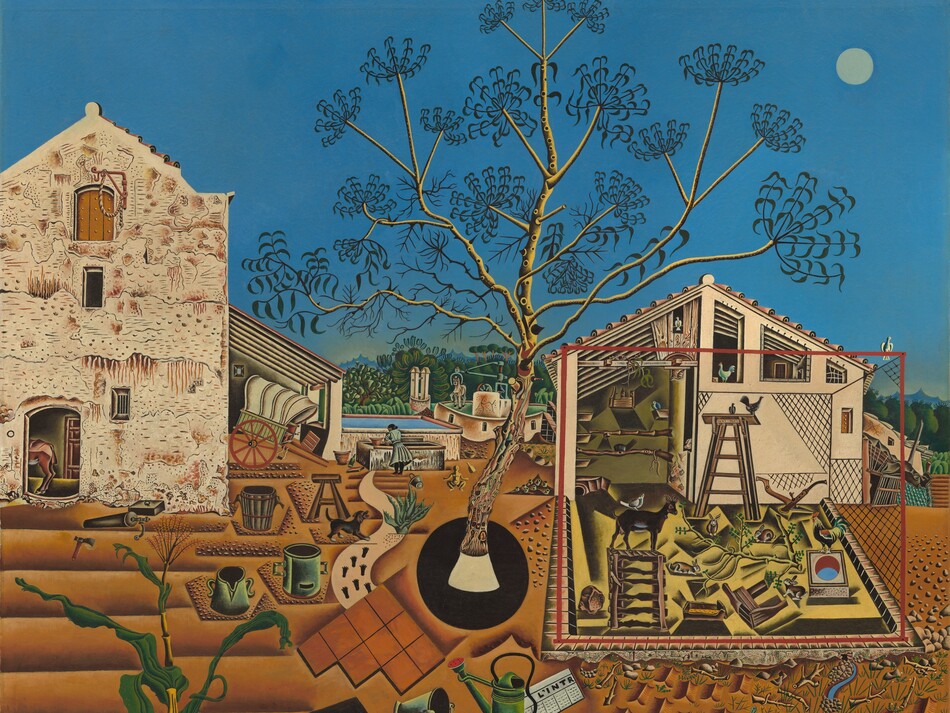

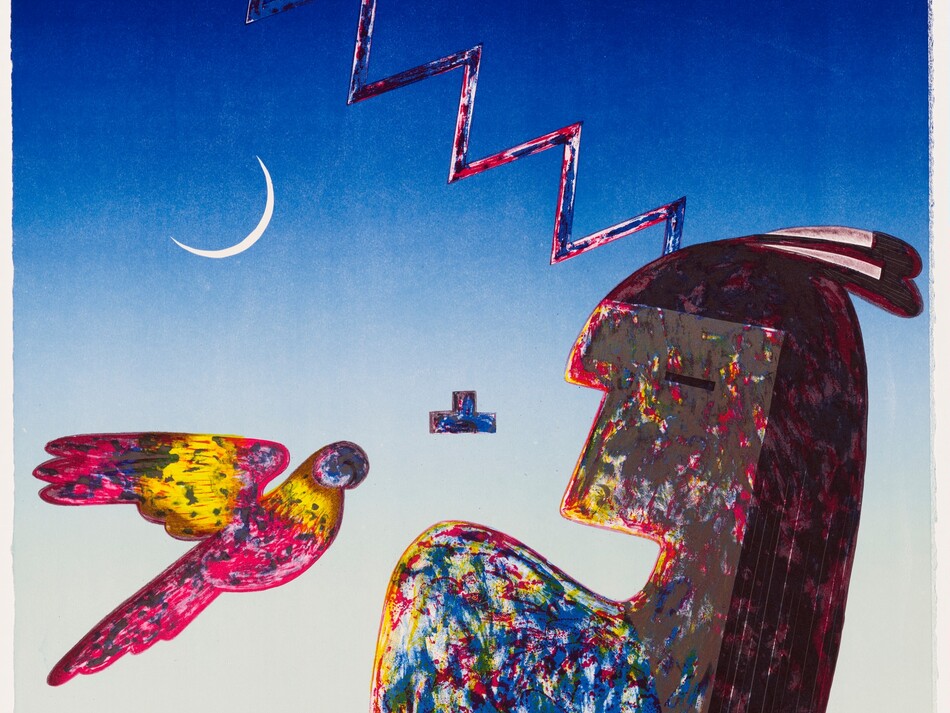

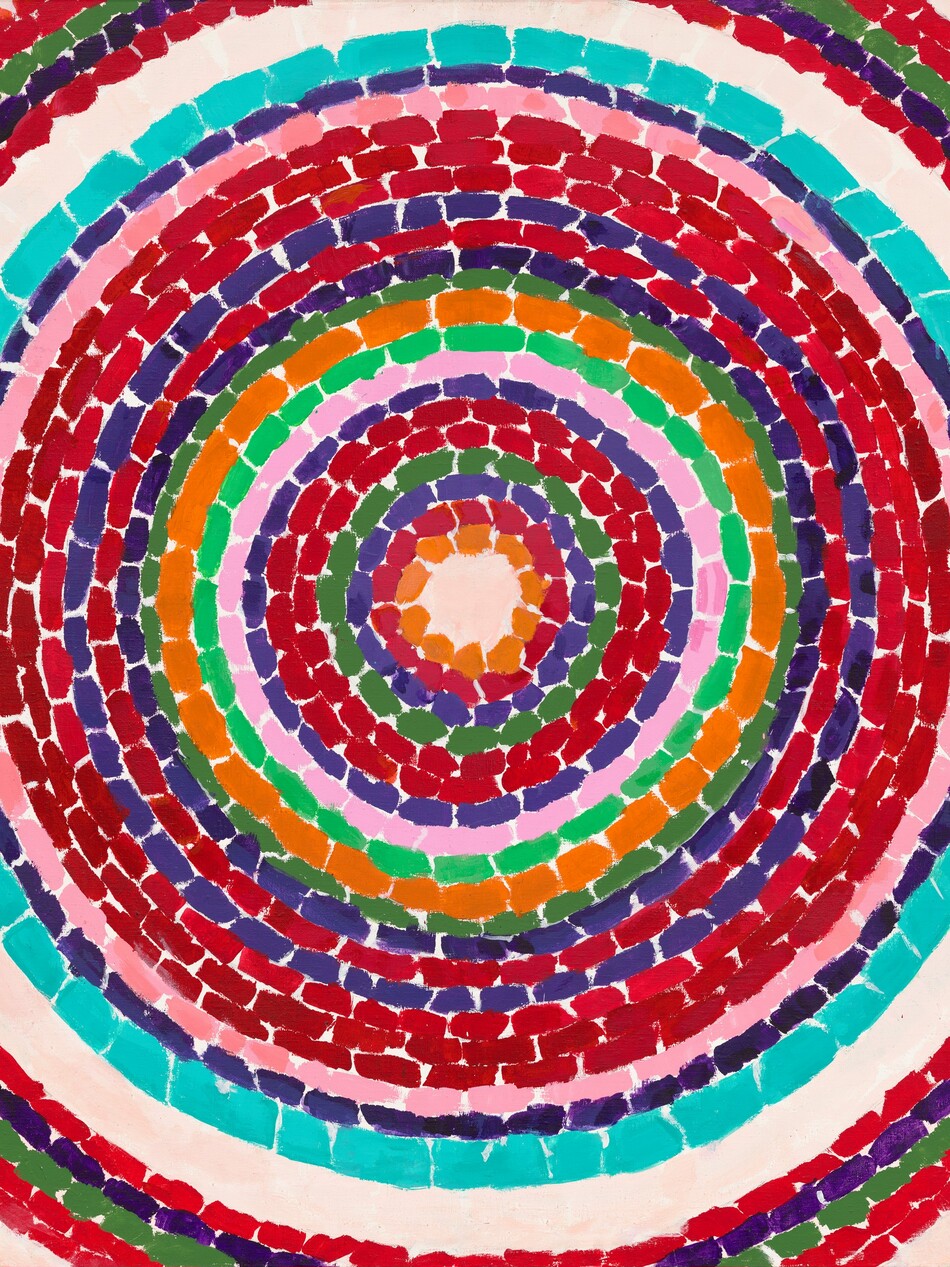

Download images

Find and download high-resolution images from our collection for use in your classroom.

Online Courses

Learn how to integrate works of art in the Gallery’s collection using Artful Thinking routines and effective strategies in two online courses for teachers of all levels and subjects.

Events : Hands-On Activities at the National Gallery

Our family programs are based on a philosophy of slowing down, focusing on one work of art, developing observation and thinking skills, inspiring curiosity and wonder, and fostering collaboration between children and adults. All Family Programs are free, and participation is on a first-come, first-served basis.