Language

On this Page:

Overview

How did the Industrial Revolution change the United States?

What makes industrialization possible?

How does art reflect the varying experiences within a capitalist economy?

In 1899 an unknown photographer documented the interior of a cotton gin operation in Dahomey, Mississippi. The image reveals the challenging and stifling work of processing raw cotton in the humidity of the southern United States. In the foreground, African Americans pack and press cotton into a massive bale. Others stand in the background next to cotton gins, machines that separated sticky seeds from plant fibers. Cotton clings to the walls and rafters of the room.

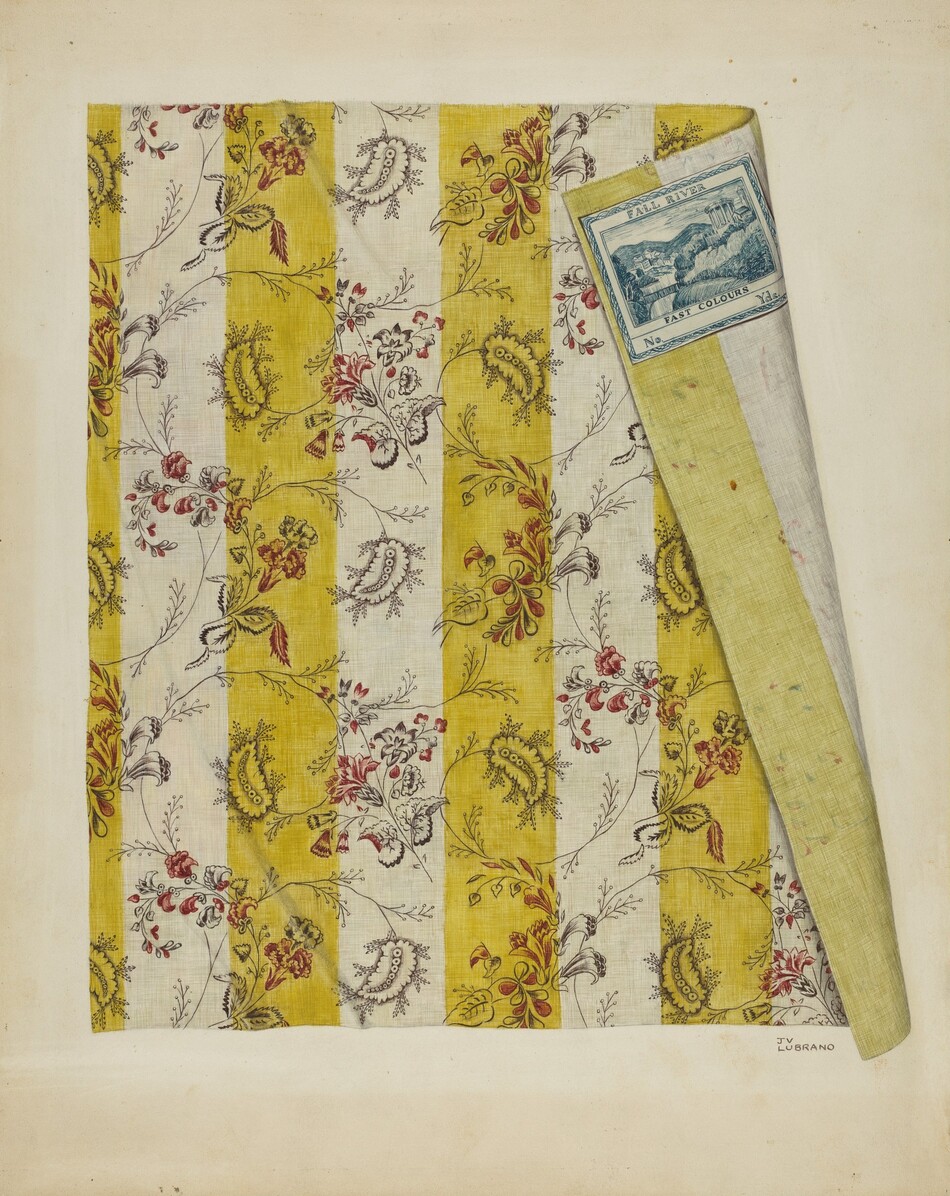

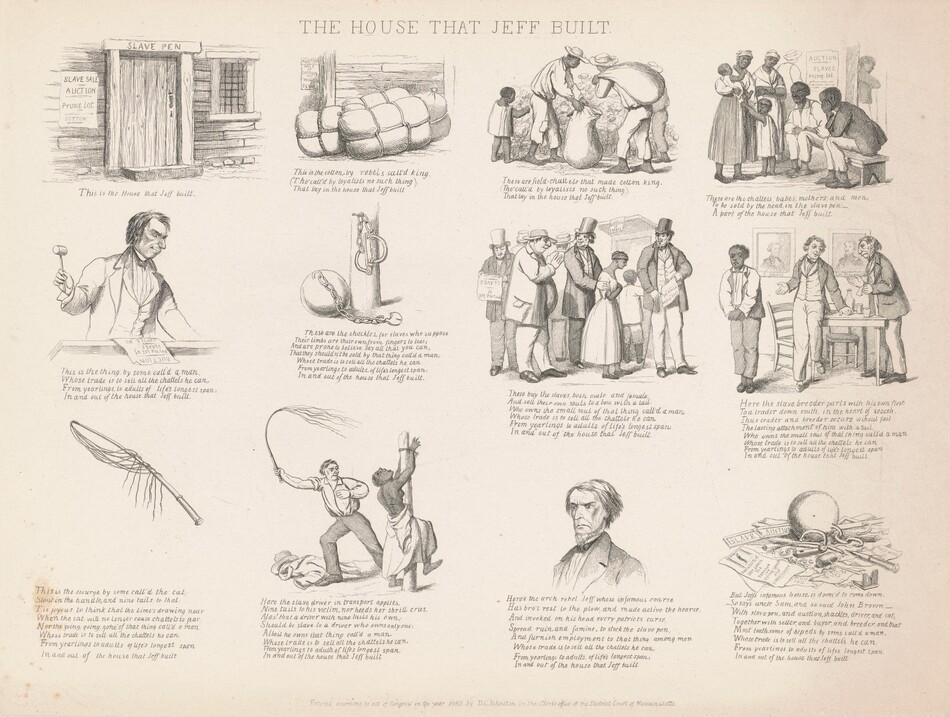

By 1860, 61 percent of the world’s raw cotton originated in the southern United States. Nearly all of this cotton was grown and processed by enslaved African Americans on lands seized from Native Americans. The cotton was shipped to industrial giant Great Britain, which imported 75 percent of its raw cotton from the United States, as well as to factories in the northern United States, where the fiber was spun, dyed, woven, and printed. Cotton was key to the United States becoming a global economic powerhouse.

The start of the US Industrial Revolution is often dated to 1793, when the first water-powered, roller-spinning textile mill opened in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. It was developed in part by Samuel Slater, an English textile apprentice who memorized British mill designs—in defiance of British laws banning their export—and then immigrated to the United States.This origin story introduces two themes that frequently feature in the larger narrative of industrialization: entrepreneurship and mechanization. It centers the Industrial Revolution in New England, where textile mills proliferated due to fast-running rivers and where workers left farms for factories over the second half of the 19th century. It also celebrates the United States as a champion of opportunity for immigrants who moved to the young country by the millions.

However, the story of the Industrial Revolution in the United States is also the story of slave labor, land exploitation, and Indian Removal. Mississippi Cotton Gin at Dahomey documents mechanized labor at what was once the world’s largest cotton plantation. Situated in the soil-rich area known as the Mississippi delta, Dahomey Plantation was named after the homeland of its enslaved workers, the Kingdom of Dahomey in present-day Benin.

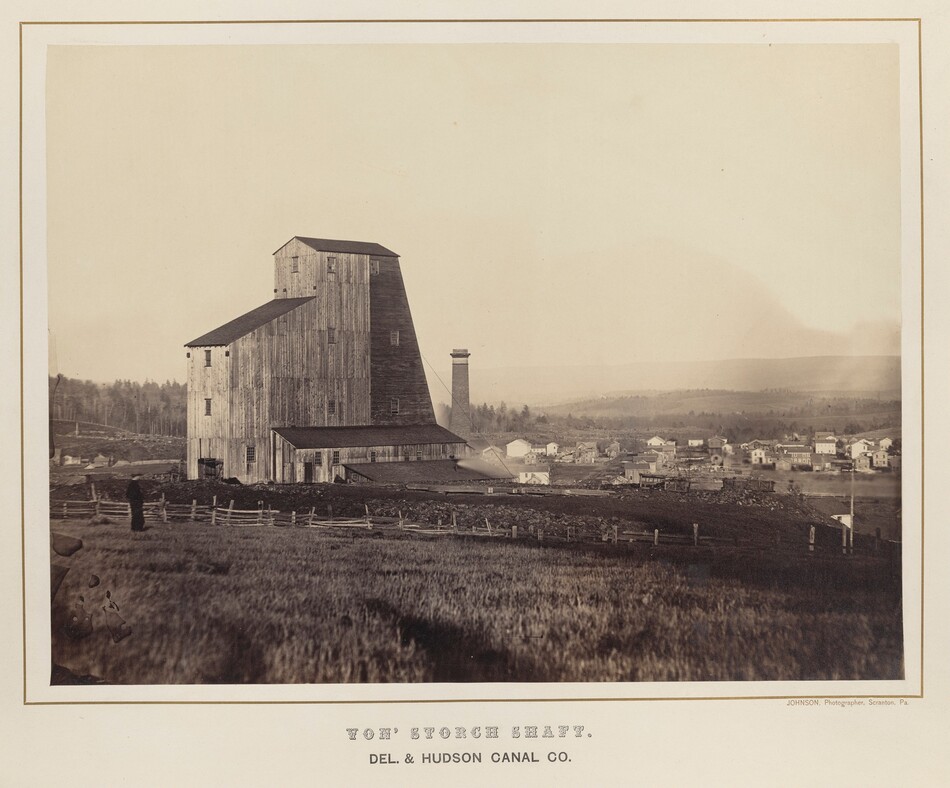

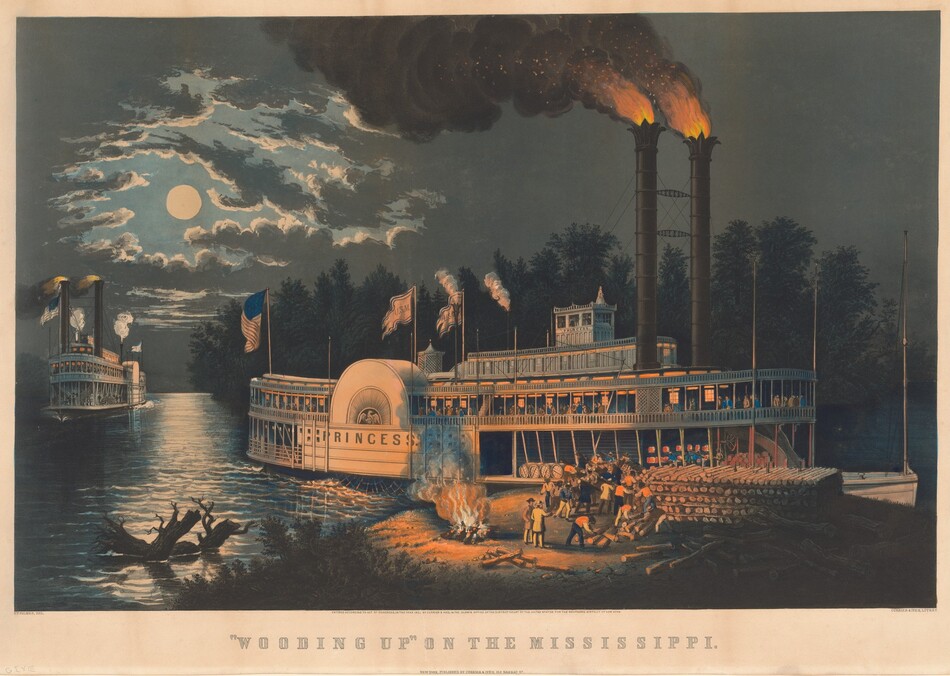

The drive to industrialize, compete, and rapidly increase wealth in the United States impacted people and lands unevenly. Artists, especially photographers, were hired to celebrate industrial achievements, particularly the construction of railroads. These same works of art often reflect the unease, tension, and loss that resulted from such development. By looking at artwork from this period, how might we gain a fuller picture of the innovations and sacrifices that led to the growth of the United States?

Selected Works

Activity: Multiple Viewpoints

Invite students to select a work of art from the image set that features people, such as Textile Merchant, “Wooding Up” on the Mississippi, or Addie Card, 12 years old. Spinner in cotton mill, North Pownal, Vermont. Encourage them to consider the multiple viewpoints or stakeholders, both seen and unseen, in the work. Next, ask them to identify a single individual and imagine that person’s point of view. Students might consider questions such as:

- What does this person gain from participating in this industry? What does this person lose?

- What does this person value or care about?

- What actions does this person engage in? How might those actions affect his or her body, mind, and emotions?

Students may use evidence that can be seen in the work of art, as well as primary and secondary sources about the industry. Ask students to contemplate the individual’s opinion of the industry. For a greater challenge, try this activity using the environment as the stakeholder.

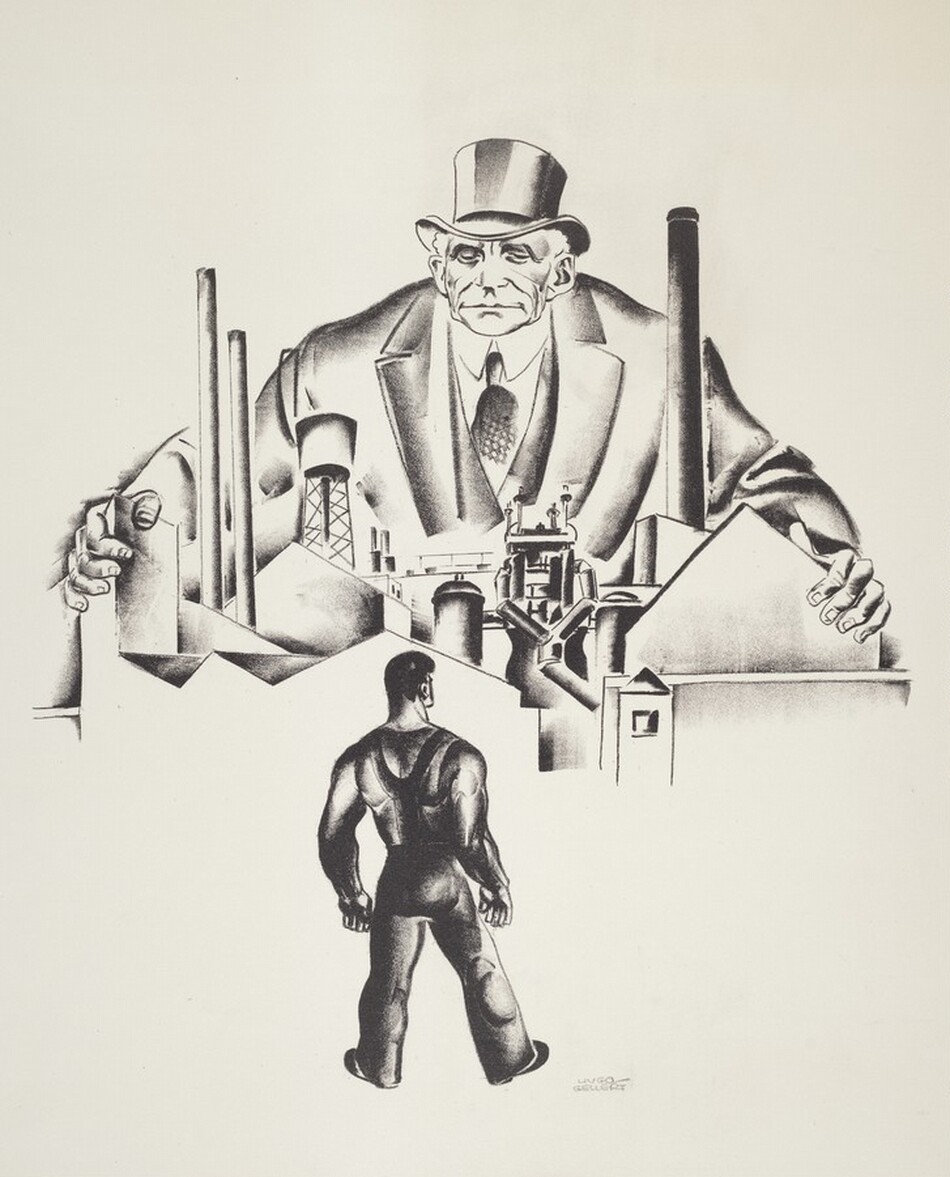

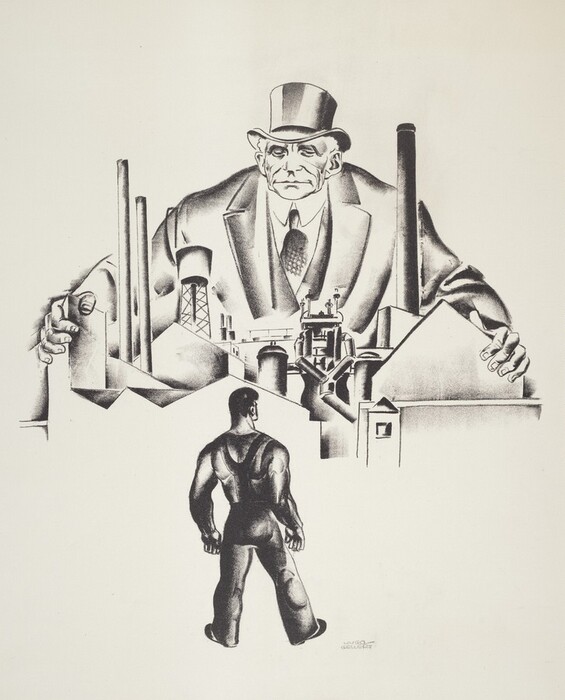

Activity: Capitalism Illustrated

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines capitalism as “an economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.” The United States is a capitalist country. People from a variety of fields and backgrounds argue about the pros and cons of capitalism, and whether it is a sustainable system. (For more background, see “What ‘Capitalism’ Is and How It Affects People” in Teen Vogue.)

Distribute images from this unit to your students and ask them to identify which work of art they think best illustrates capitalism and why. Then, invite them to conduct more research into arguments for and against capitalism and ask them to take a position on the system.

Activity: Industry Then and Now

Industries developed across the United States in the 19th century as settlers spread across the country and claimed lands. New industries continue to emerge today. Ask students to investigate their community: What was its primary economic driver in the past? What is its leading business today? Consider what made these industries possible, such as geography, immigration or migration, climate, and education. Invite students to reflect on the benefits and downfalls of today’s industry, consulting with friends, family members, and neighbors in order to gain multiple perspectives on the local industry. Students should then create a portrait of industry in their community. They might try the following:

- Create a portrait of an industry worker

- Photograph a physical site or building

- Tell a visual or graphic story of the industry

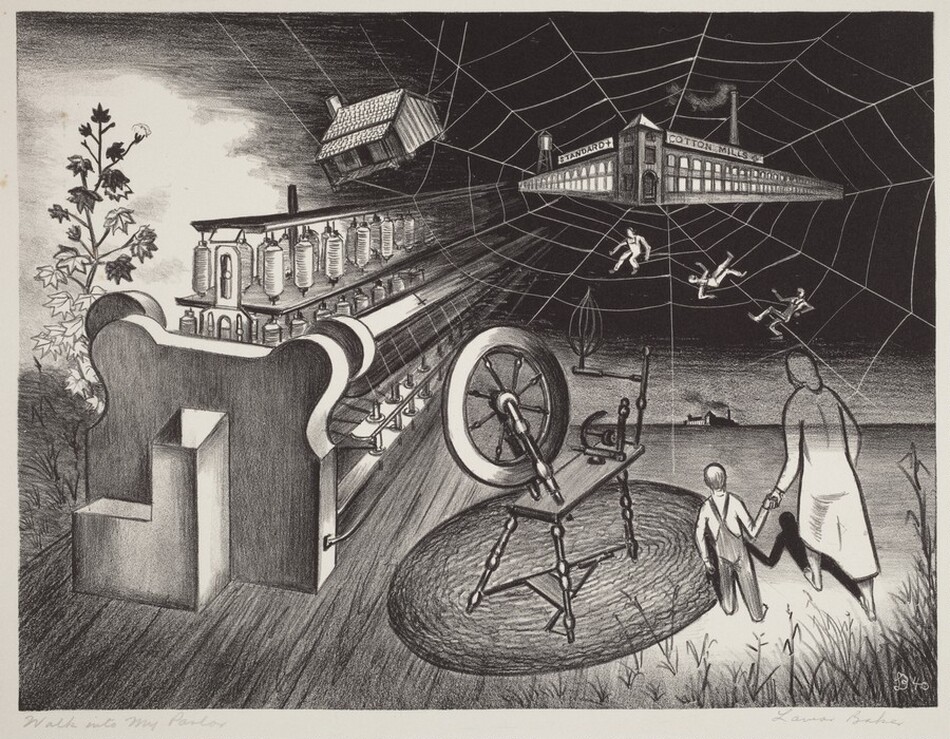

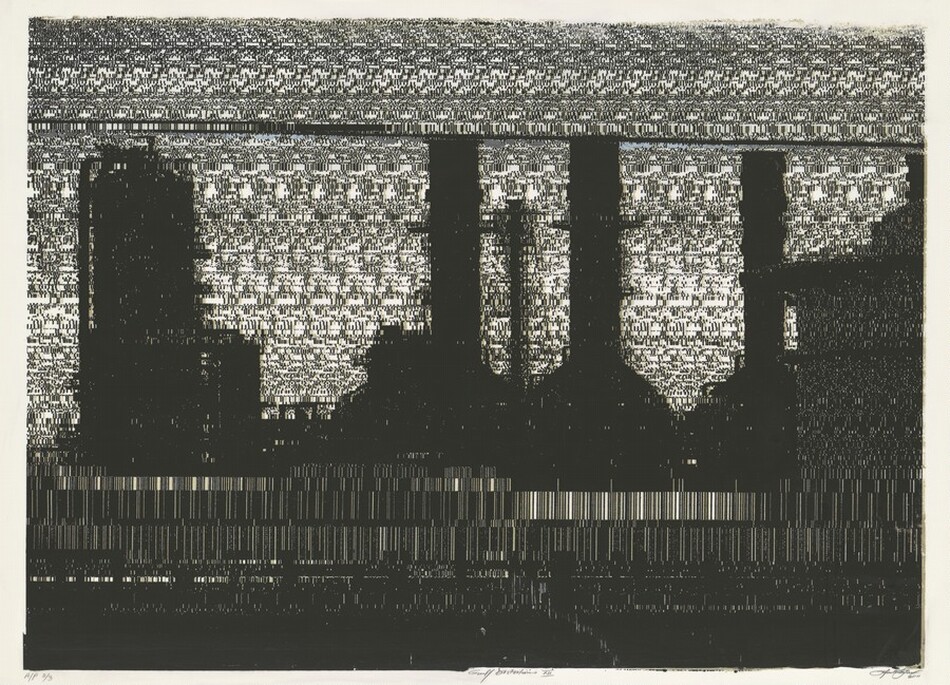

What colors, lines, shapes, patterns, or symbols can be employed to make the works of art more meaningful? Offer examples of symbols from the image set, such as a broken tree stump (George Inness’s The Lackawanna Valley) or a spiderweb (Lamar Baker’s Walk Into My Parlor), as well as Soledad Salamé’s use of distortion to create meaning in Gulf Distortion XII.

Additional Resources

The Industrial Revolution in the United States, teacher’s guide, Library of Congress

Caitlin Rosenthal, “Plantations Practiced Modern Management,” Harvard Business Review, September 2013

Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Vintage, 2015)

You may also like

Educational Resource: Immigration and Displacement

The United States is frequently described as a “nation of immigrants.” Immigrants have played a pivotal role in the country’s history and understanding of itself.

Educational Resource: Faces of America: Portraits

The basic fascination with capturing and studying images of ourselves and of others—for what they say about us, as individuals and as a people—is what makes portraiture so compelling.