Language

On this Page:

Overview

In what ways have Americans impacted the environment?

What is our collective responsibility toward the earth and each other?

How do artists engage with these questions through works of art?

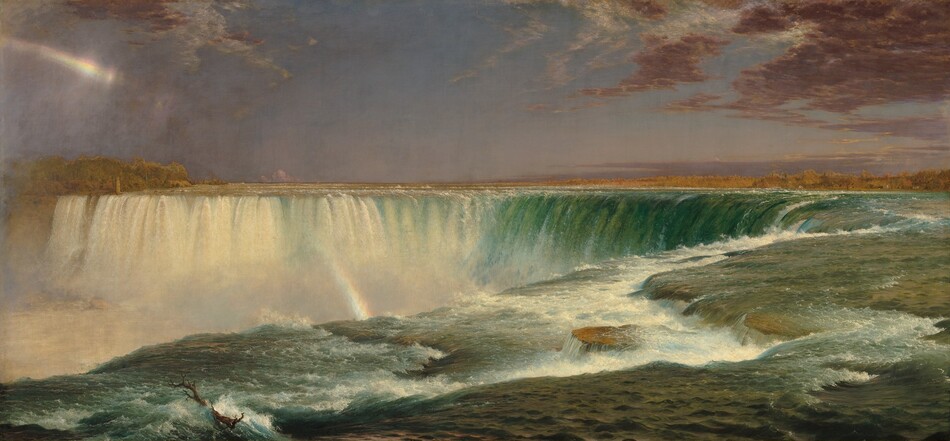

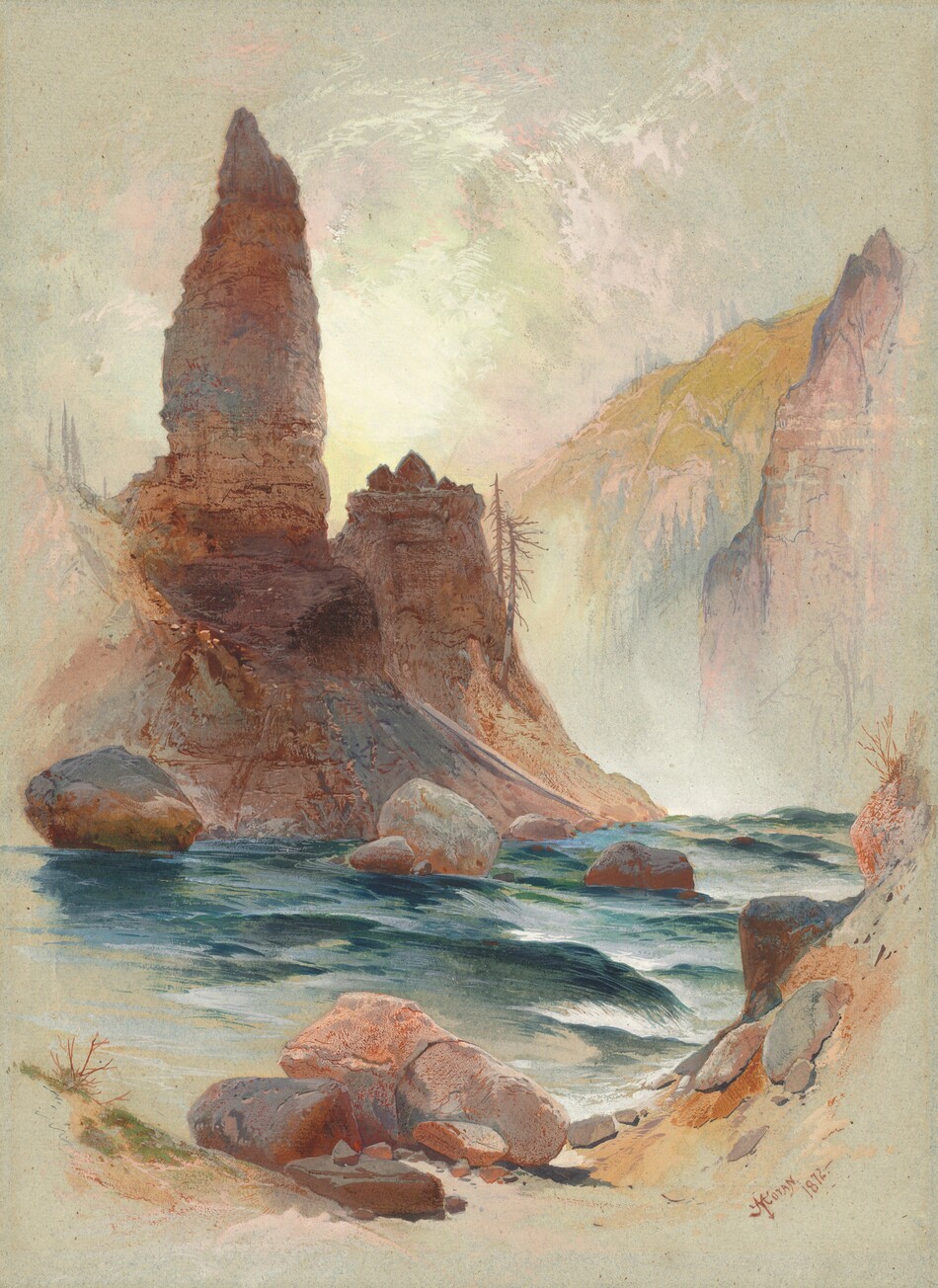

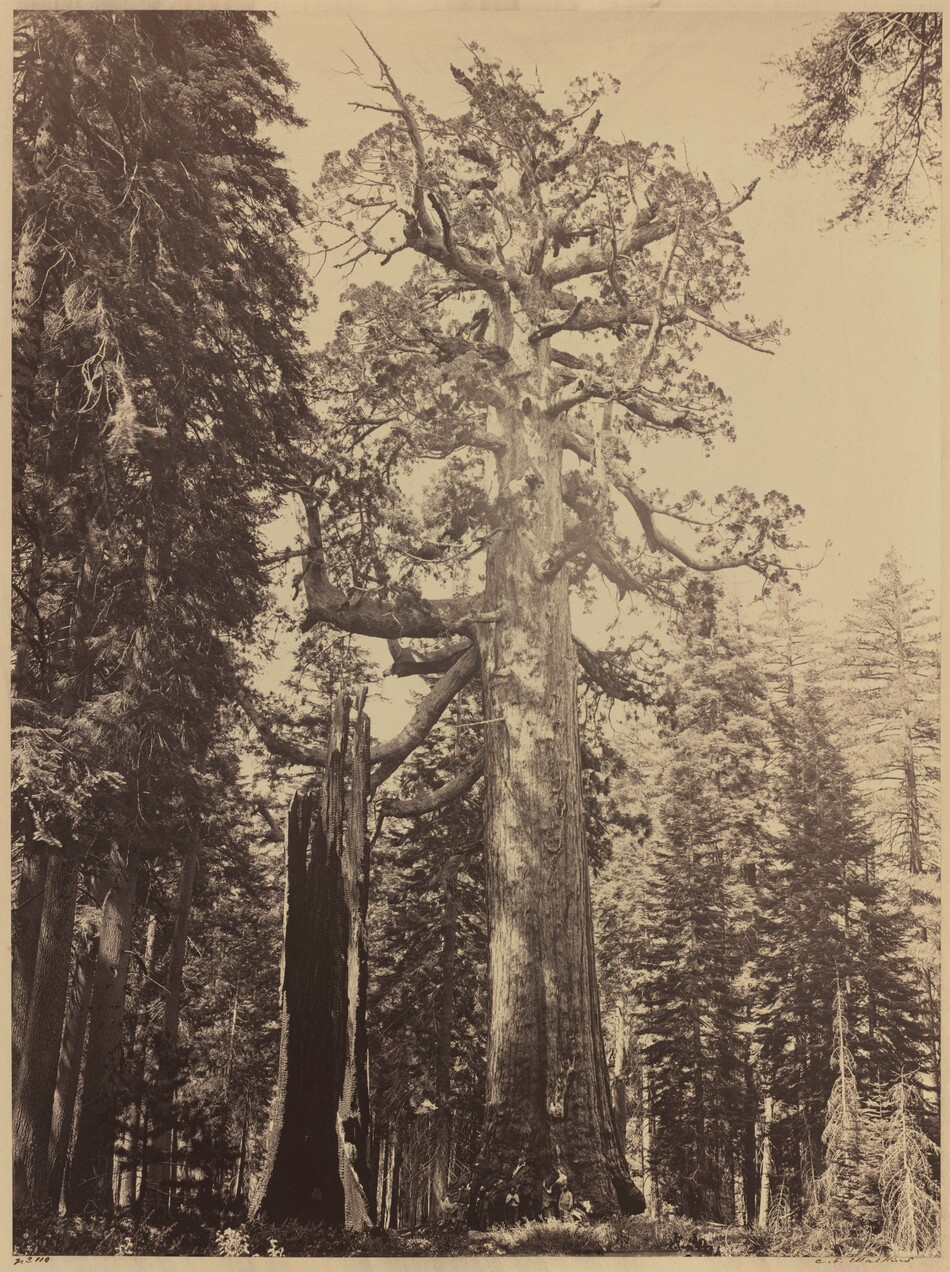

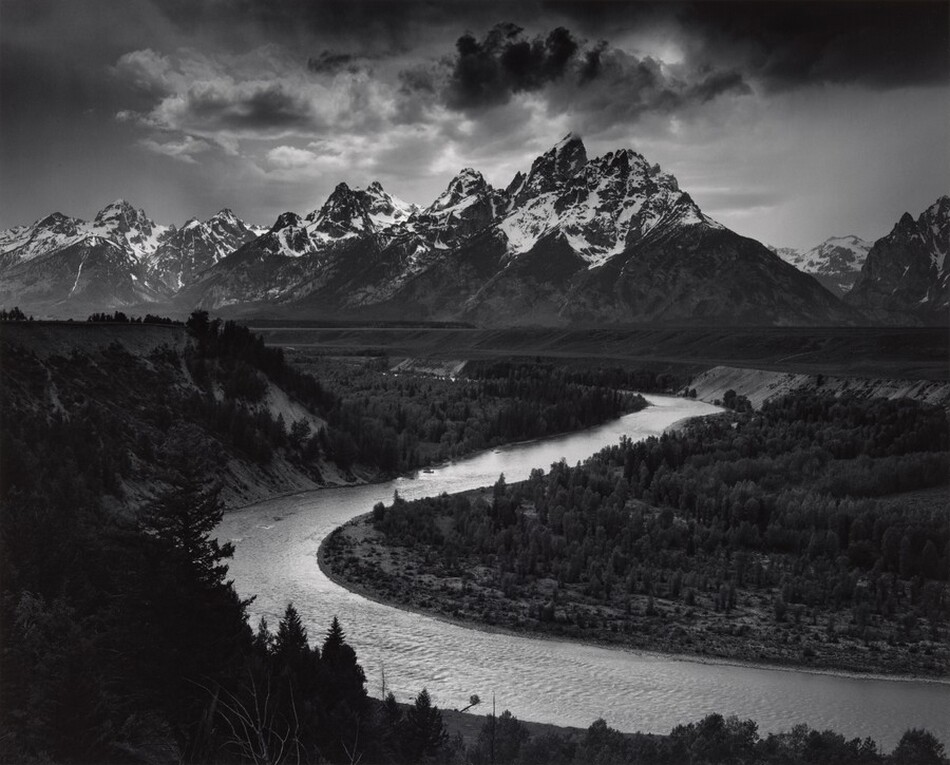

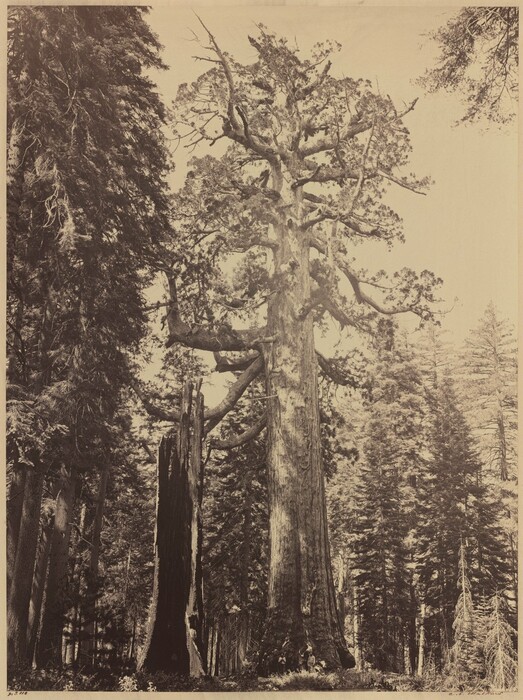

The US national park system exists in part because of artists. Photographer Carleton Watkins’s mammoth photographs and intimate stereographs of Yosemite, including Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove, convinced a senator to propose a new bill to the US Congress reserving lands for public use. In 1864, President Lincoln signed legislation that set aside Yosemite and the Mariposa Grove as a state park for California—the first time that the federal government had ever created public parklands. The world’s first national park, Yellowstone, was established in 1872, only a few months after artist Thomas Moran traveled to the area as part of an exploratory expedition. Moran’s breathtaking watercolor studies of the area, complemented by William Henry Jackson’s photographs, helped persuade Congress to designate Yellowstone as a park “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove and Moran’s Tower at Tower Falls, Yellowstone may evoke memories or associations if you’ve traveled to the national parks, as millions of US and international visitors do annually. Local or regional parks may surface in your mind, too. Looking closely at these works of art and learning about their significance might also spark questions:

- Why did the artists choose to depict these particular natural elements and settings?

- Why and how did these works of art successfully convince lawmakers to enact new laws?

- How did viewers see and experience these works of art?

- Why did these works of art become so widespread and popular?

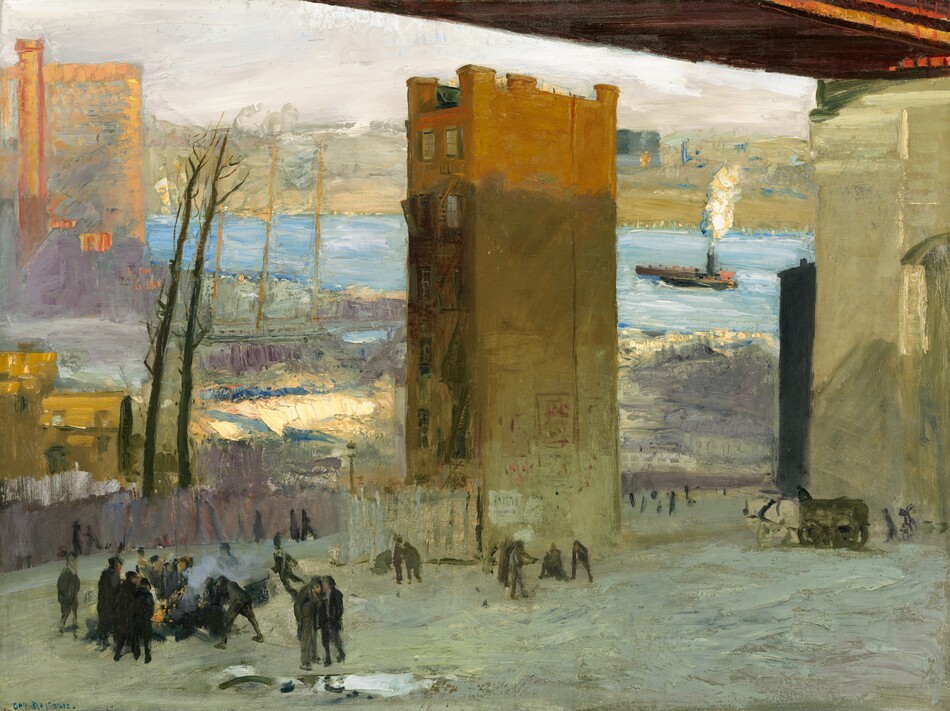

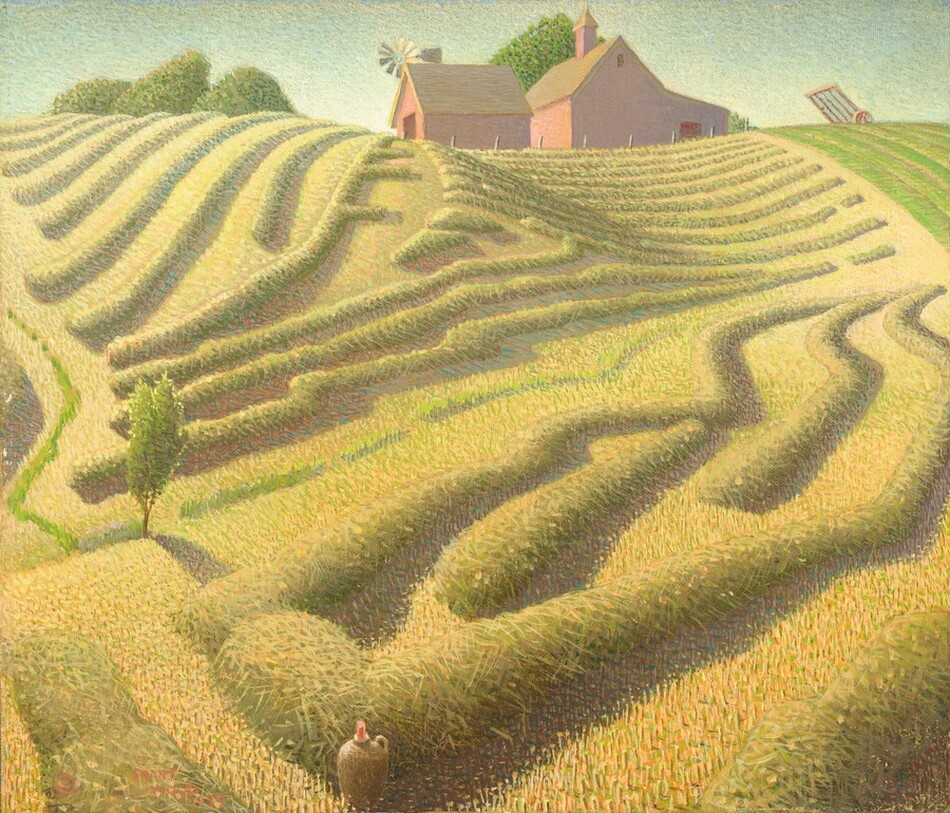

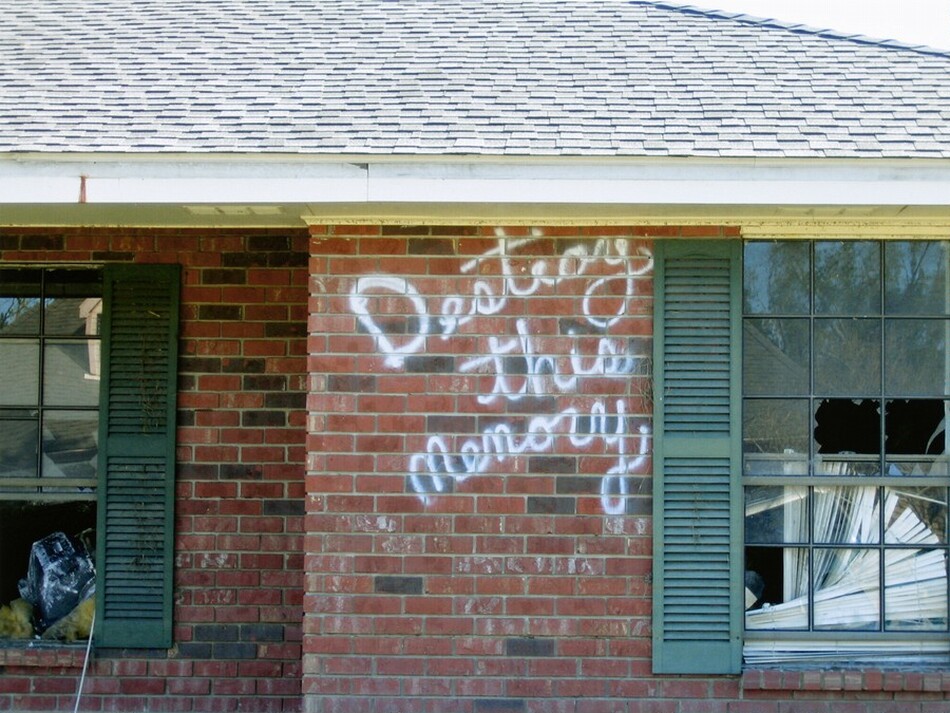

The US landscape is a source of pride, national identity, and pleasure for many, in part because artists like Watkins and Moran helped shape and reinforce these understandings. Their works celebrate the expansive forests, rugged mountains, and great lakes and waterways of the country. But the land is also contested and controversial. By the 19th century, millions of indigenous people, including those in Yellowstone and Yosemite, had been killed by disease and warfare, or forcibly removed from their ancestral homes to make way for settlers. In California in particular, thousands of Native people were murdered in militia raids sanctioned by the US government, leading many scholars to identify what happened as genocide. Innovations such as the railroad and agricultural mechanization made life easier and more efficient, but they also turned nature into a commodity. Today, trees, water, and other resources continue to be extracted, bought, and sold to benefit a booming export industry and a growing populace.

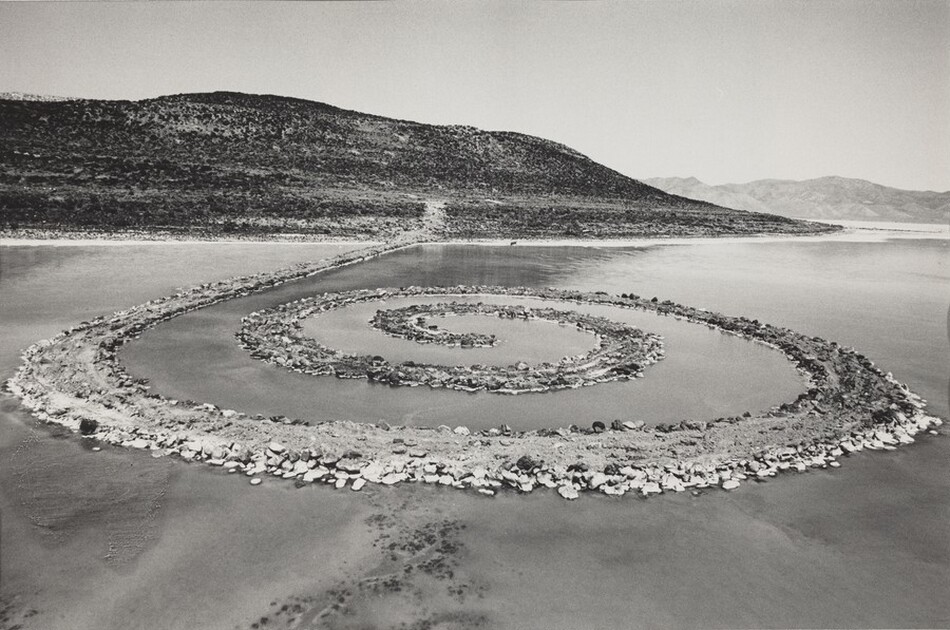

When land is claimed or transformed, who is affected and how? What does the natural world mean to various individuals, communities, and cultures? Why and how might we protect and sustain limited natural resources while making them available to the public?

As populations around the world increase and humans continue to upset the earth’s climate, striking a sustainable balance between human activity and nature becomes increasingly vital and difficult.

Selected Works

Activity: Poetry, Art, and Nature

Poets and visual artists alike create work about the natural environment. Read through the poems listed below with your students. What are the poets’ points of view, and what sentiments are the poems expressing about nature? How do they evoke the reader’s senses? What emotions or thoughts do you have after reading the poems?

- “Patience Taught by Nature,” Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- “What Kind of Times Are These,” Adrienne Rich

- “Some Effects of Global Warming in Lackawanna County,” Jay Parini

- “Remember,” Joy Harjo

Compare the poems to the works of art collected in this module. Are there any poems that complement particular works of art? How are they similar, and how are they different?

Activity: Community Artists/Scientists

Community scientists (also known as citizen scientists) are people who conduct research and contribute data to science projects as amateurs or nonprofessionals. Anyone can participate in community science projects provided they follow guidelines established by hosting organizations, including National Geographic, NOAA, and NASA.

Using the model of community science, identify a science project that aligns with your students’ interests and learning goals. Conduct research that both contributes to science and can be used to make art that reveals or communicates something about the climate in which you live. Artworks can take any form and use any medium.

Creating art is one way to take action in response to the world’s changing climate. What are other concrete ways that you see people helping solve this challenge? How might you, individually or with others, contribute solutions or make change in your own school or community?

Additional Resources

Art and Ecology Lessons and Activities, National Gallery of Art

From Pursuit to Preservation: The History of Human Interaction with Whales, New Bedford Whaling Museum

National Zoo and Aquarium Month: Preserving America’s Wildlife, National Endowment for the Humanities

Environmental Protection Agency

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Global Climate Change, NASA

You may also like

Educational Resource: Immigration and Displacement

The United States is frequently described as a “nation of immigrants.” Immigrants have played a pivotal role in the country’s history and understanding of itself.

Educational Resource: Expressing the Individual

Studying artists and their works invites explorations of identity and the human condition. What drives artists to create? What choices do artists make, and why? Sometimes artists directly engage with questions of identity in their artwork: Who am I? How do I relate to others, and how do they relate to me?

Educational Resource: Harlem Renaissance

How do visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance explore black identity and political empowerment? How does visual art of the Harlem Renaissance relate to current-day events and issues? How do migration and displacement influence cultural production?