Abbey Stockstill

Color Through the Seven Spheres: Materiality and Vision in Medieval Islamic Architecture

Dawn over the Alhambra, c. 2014. Creative Commons License

According to the medieval polymath Ibn Sina, the spectrum of light traveled along one of three paths in its journey from white to black: through red, green, or the nebulous hue al-adkan, alternatively translated as yellow-green or gray. Though simple, these colors encompassed an entire range of shades that comprised the basis for a color vocabulary among medieval Arabic writers in their descriptions of the world around them. Contrary to the widespread and well-documented theories of Islamic aesthetics, which advocated for a proportional and organized scheme of high contrasts between colors, several notable sites across the premodern Arabic-speaking world became known in conjunction with a singular color, not only in their material documentation but in the ways medieval authors wrote about them. Precisely what these colors were intended to communicate, and how they did so, has formed the basis for my research at the Center for the past year, on a new book project tentatively entitled “Color Through the Seven Spheres: Materiality and Vision in Medieval Islamic Architecture.”

Envisioned as a critical theory of color in the architecture of the Arabic-speaking Islamic world, the project integrates a technical art-historical approach with key works of intellectual history to conceive of color in the Islamic world as an active component in both visual reception and psychological communication. Each chapter is organized around an architectural case study associated with a singular color, following the spectrum outlined by Ibn Sina, and uses that case study to explore how materiality and process inform and exploit the semantic associations of that color. Key to this process has been the study of two works of philology: Kitāb al-taṣārif al-afʿal (Book on the conjugation of verbs) by Ibn Qutiyya (d. 977), which discusses how the terms for colors are articulated from their verbal roots, and the German Arabist Wolfdietrich Fischer’s Farb- und Formbezeichnungen in der Sprache der Altarabischen Dichtung (Color and form descriptions in ancient Arabic poetry), which traces the development of color terms across a variety of Arabic dialects. Whereas medieval optical science understood color as a property of light, related to other colors along a spectrum, philology understood color as a property of action, carrying with it the haptic experience of color, both tactile and visceral. I argue that this understanding was echoed in the material production and materiality of medieval color production, such that colors held the potential to evoke more complex meanings through the nature of their materiality.

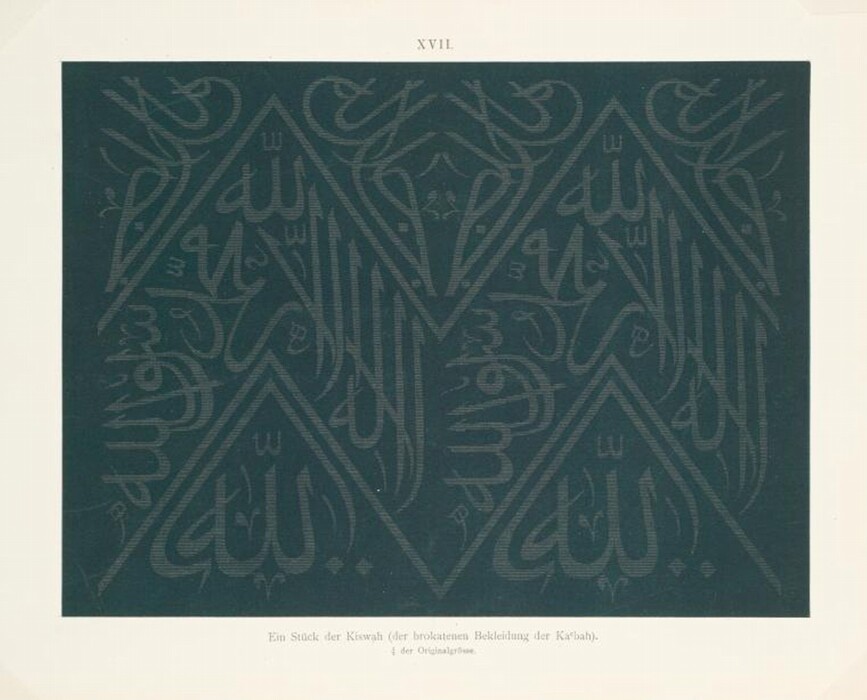

Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, “Ein Stück der Kiswah,” from Mekka, mit Bilder-Atlas (c. 1888–1889), New York Public Library

This year, I have focused on two chapters of the book manuscript in addition to the underlying theoretical structure, “Ahmar” (red) and “Aswad” (black). The chapter on red is centered around the 14th-century fortress known as the Alhambra, the “red castle,” which derives its distinctive color from the presence of iron in the local clay. During the firing process, the iron oxidizes, taking on varying shades of ocher. In Arabic, red was associated with the sensation of burning, both in the physical sense of heat but also in the more mystic sense of prophecy. I connect this to the larger sphere of material culture produced and collected under the Nasrids (r. 1232–1492), who utilized the prophetic connotations of red in light of existentialist fears in the face of Castilian expansion.

The chapter on black focuses on the Kaaba, the central monument in Islam whose silk covering, known as the kiswa, has traditionally been black since its production in Cairo beginning in the mid-13th century. I trace how the kiswa came to be black after several experiments with other colors, and the role that writing, calligraphy, and weaving play in its production. Black carried the connotation of covering with writing, of literally blackening a surface with ink. The color was much theorized in the collection and codification of the Qur’an, and that theorization, I argue, was interwoven with the kiswa as a garment of talismanic potential. Although few extant examples of medieval kiswas remain extant, I have been able to identify two potential samples for scientific analysis, and other documentary evidence suggests that the kiswa was traditionally woven in a black-on-black pattern of Qur’anic verses and apotropaic phrases.

My time at the Center has allowed me to develop the initial theoretical framework for this project, and to make significant progress in drafting two of the book’s five case studies. Other chapters on green, white, and al-adkan are planned, and I am confident that the research undertaken in this past year has laid the foundation for a dynamic and innovative approach to the field of color in Islamic aesthetics.

Southern Methodist University

Paul Mellon Senior Fellow, 2024–2025

In August 2025, Abbey Stockstill will assume the position of associate professor and Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Chair of Architectural History at the University of Virginia.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.