Wenjie Su

Simulating Time, Modeling Cosmologies: Clockwork Art Between Early Modern Europe and China

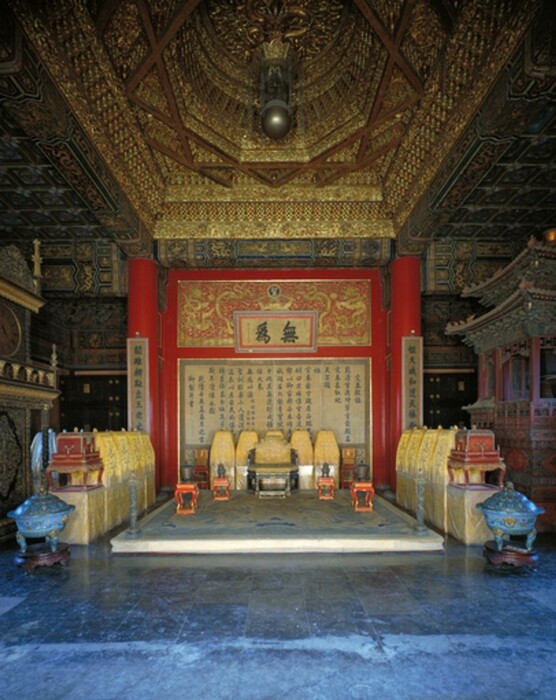

The Hall of Union and Peace, Palace Museum, Beijing. The symmetrical placement of the Grand Mechanical Clock and the Grand Clepsydra were decreed by the Qianlong Emperor in 1761.

Can meetings on earth entail collisions between heavens? Engaging with recent scholarship on the First Global Age (c. 1450–1750), my dissertation research highlights the inertia of cosmological worldviews in an increasingly interconnected early modern world. Despite expanding networks of trade, diplomacy, and evangelization spanning the transatlantic, transpacific, and Eurasian spheres, societies newly drawn into global contact remained grounded in distinct and often incompatible cosmological frameworks, shaping the dynamics of cross-cultural exchanges and imperial encounters. Is there a beginning of time and space? How is human existence situated within the cosmic order? Are there many universes, or only one? These questions—shared across civilizations—exceeded the observational and technological capacities of early modern minds in any tradition. My dissertation explores how art was created and exchanged in response to these shared epistemic blind spots, which often manifested themselves as ideological divides.

Clockwork art—mechanical timepieces, automata, and cosmic machines—stood at the heart of Ming and Qing China’s encounters with various European interlocutors. By tracing the circulation of horological technologies, mechanical designs, and cosmological ideas across early modern Eurasia, this project connects Jesuit polymaths active in multiple cultural centers, clockmakers and Royal Society intellectuals in London, priest-astronomers in central Europe, literati in southern China, artists at the High Qing court in Beijing, and merchants navigating the transpacific sphere. Traditionally, scholars have studied premodern clocks and automata as elite curiosities or precursors to industrial machines. My research challenges such positivist narratives by demonstrating how clockwork devices circulated as material emblems, at one extreme, for debating the origins of the universe and, at the other, for envisioning (in)finite futures.

Since the physical reality of time is not directly visible within our three-dimensional world, the conception and creation of timepieces necessitated an artmaking process—one that fused empirical knowledge with cosmological imagination. While Jesuit missionaries established God as the divine clockmaker and situated all human cultures within a singular theological timeline, British merchants and diplomats leveraged cosmic machines to picture a reciprocal future powered by the engine of free trade. In response to European teleologies of time, 18th-century Qing patrons reinvented traditional water clocks to simulate the spontaneous and ever-changing cosmic formations fundamental to Chinese natural philosophy. Rather than advancing toward a utilitarian or industrial vision of mechanized productivity, early modern European and Chinese patrons alike valued dynamic iconographies and material intelligence unique to mechanical design. Clockwork was employed as both technology and art—animated to model cosmological beliefs, to visualize what lay beyond the optical horizon, and to negotiate cultural and ideological chasms. I argue that early modern encounters between Europe and China revealed the divergent origins and directions of two momentarily entangled threads of time.

William Alexander, From the Planetarium, the Principal Present to the Emperor of China, from an album of 278 drawings of landscapes, coastlines, costumes, and everyday life made during Lord George Macartney’s Embassy to the Emperor of China, 1792–1794, pencil, pen and ink, wash and watercolor on paper. © British Library Board, WD 961, fol. 122

A cornerstone chapter of this dissertation will appear in the Science Museum Group Journal, titled “Between Greenwich and the Forbidden City: Asynchronicity in the Connected Early Modern World.” By unpacking the resonance between three pairs of synchronized timepieces, this article examines how the shape of time was negotiated—across conflicting chronologies, between God-created and self-generating universes, and through artificial simulations of natural time. The first concerns the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, where a pair of identical regulator clocks (1676) revolutionized astronomical observation and maritime navigation, furthering the ideal of a unified global temporality. Meanwhile, the German polymath and sinophile Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) used the thought experiment of two perfectly synchronized clocks to envision preestablished harmony in a divinely ordered universe—an idea he extended to intercultural reciprocity. And, finally, a few decades later, in the Forbidden City, the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796) staged a dialogue between a European-style clock and a Chinese clepsydra. Rejecting the Jesuit-imported creationist worldview, Qianlong embedded mechanical timekeeping within an architectural matrix of yin and yang energies, believed to generate a self-renewing and perpetual universe. As modern physics has since shown through general relativity, time is not an absolute measure but varies with the observer’s frame of reference. My research reveals how early modern cross-cultural exchanges presaged relativist conceptions of time. When clocks moved between early modern Europe and China, they were not merely relocated in space, but their very temporal meanings were transformed. These relocated clockwork objects were visually and technically adapted and, more importantly, absorbed into divergent trajectories of time that had not yet been globalized.

Princeton University

Samuel H. Kress Fellow, 2023–2025

Beginning in fall 2025, Wenjie Su will join the Art History program at the University of Arkansas as a faculty member.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.