Chang Tan

Network Moderns: Vernacular Photography and Image-Making in Global Chinas

My project explores how “staged” studio portraits, cocreated by practitioners of photography, painting, design, and theater, crafted vernacular modernisms from the cultural margins. In five chapters, I track the making, circulation, and usage of such images across the “global Chinas,” which include British Hong Kong (late 19th century), San Francisco Chinatown (1920s–1940s), Japan-occupied Taiwan (1898–1945), and the People’s Republic of China (from the Mao Era [1949–1976] to the present day), and study the visual experiments conducted by their makers and users. Linked through transpacific movements of peoples and material cultures, these artists responded to and reimagined diverse visual modernities—colonial, Diasporic, Indigenous, socialist, and post-human.

Through case studies of photo studios and the cultural industries with which they partnered, I demonstrate how vernacular photographic image-making was neither the expression of individual artists nor an indexical record of the ephemeral, but prolonged processes in which photographers negotiated, clashed, and collaborated with sitters, viewers, and other participating artists, such as backdrop painters and costume designers. At the same time, I argue that the collaborative process is the very factor that makes such vernacular images modern. In this process, divergent and competing media can be mutually incorporated to form a multimedia art in which the discrepancies between representational modes open space for re-creation. Each medium probes into its own peculiarity while competing with and adapting to the others, resulting in a bricolage. The collaboration also facilitates connections between diverse traditions and regions, mirroring the varied background of its participants while embodying the cosmopolitan aspirations of its viewers/users, even though many of them were trapped in a fixed locality due to repression, discrimination, or hardship.

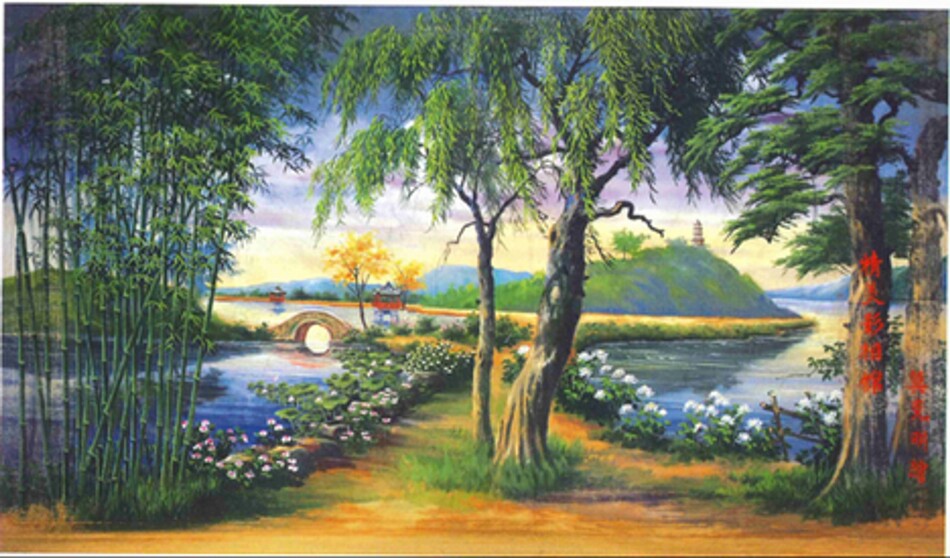

A fellowship from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (2022–2023) allowed me to conduct archival research in institutional and private collections in the United States, Taiwan, and China. My residency at the Center offered me the time, resources, and intellectual support to complete two chapters. One examines the rich trove of prints, negatives, and ephemera from May’s Photo Studio (1923–1945) in San Francisco, founded by the Chinese American couple Isabelle May (1889–1968) and Leo Chan Lee (1893–1976). The studio operated in close alliance with two cultural industries that grew rapidly in China and became global in the early 20th century, backdrop painting and Cantonese opera, and their collaborations generated contested identities and new pictorial possibilities. The resulting images, I argue, embodied and reimagined the Chinese Diaspora. They created optical illusions that reflected the conundrums of cultural hybridity, fabricating glamorous surfaces that conveyed material as well as emotional cravings, and using multilayered verbal and pictorial signage to channel virtuosity, prestige, and political relevance across borders. This chapter also rediscovers the lives and careers of lesser-known artisans who sought recognition yet left few traces in written history, such as the backdrop painter Mok Kug Ming (active 1920s–1940s), whose surviving works convey the sensibilities and savvy typical of the Diaspora—clever self-promotion, mindfulness of diverse audiences, and a deep-seated hybridity that renders the question of authenticity moot.

Using journals, catalogs, and photo albums from the Library of Congress as well as various private collections, my other chapter studies staged photos in the Mao era. All commercial photo studios became state-owned in China in 1958, and their practices were heavily regulated to serve the dominant cultural-political ideology. Staged photographs were criticized for their departure from the “realistic” claims journalistic and artistic photographs sought at the time. Studio operatives and customers, however, continued to stage personal fantasies in photographs, and their fantasies could precede, echo, or subtly defy dominant ideological agendas. Examining popular motifs used in those images, such as industrialized landscapes, cars, airplanes, and rockets, as well as images or writings of Mao, I show how staged portraits functioned in multivalent ways: they acted out and contributed to the larger utopian visions of the socialist modern; at the same time, their persistent references to myriad times and spaces, together with their blatant artificiality and surprising intimacy, belied and punctured the prevailing images of totalitarian utopia.

In all my case studies, I highlight the signifying power of the vernacular. Unlike what we find in written histories, the vernacular is troublingly promiscuous, mimicking dominant discourses and, at the same time, falsifying them through performances of excess. My project advocates new research methods and ways of looking that help put the vernacular on the global map of modern visual culture.

Pennsylvania State University

William C. Seitz Senior Fellow, 2024–2025

Chang Tan will return to her position as associate professor of art history and Asian studies at the Pennsylvania State University.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.