Rashmi Viswanathan

Ambassadors of Art: State and Culture Across Borders

“Ambassadors of Art” considers modern art in international art exchanges and cross-cultural exhibitions in and between India and the United States during the long 1960s. During a period of shifting and sometimes volatile relations between India and the United States, modern art exhibitions were exchanged through cultural diplomatic missions intended to advance national political and economic interests. American state interest turned to India in the 1960s as the newly independent nation’s economy offered potential markets for American products, and art promised a cultural face for the development of economic relations. In this same period, varying Indian national desires pulled its institutions toward third-worldist alliances, or ricocheted between affiliations with the United States and the Soviet Union. “Ambassadors of Art” looks at how modern art moved between nations through exhibitions, providing insight into how national culture developed as a global phenomenon amid the unrest of the 1960s.

My project comprises four case studies that consider the people and processes that made global art discourse possible as achieved through the vehicle of cross-cultural exhibitions. Its historical stage extends beyond artists and artworks to include the bureaucrats, laborers, and curators who enabled, executed, or even undermined diplomatic agendas for modern art in transnational circulation. I argue that the stories of these situated actors, who are conventionally excluded from art’s histories, not only narrate how art enters the domain of “global,” but also chronicle the hopes and dreams of arts advocates working in and against the nation. By paying attention to artists alongside exhibition builders and art handlers alongside institutional functionaries, “Ambassadors of Art” thinks about social histories of global modernity in art.

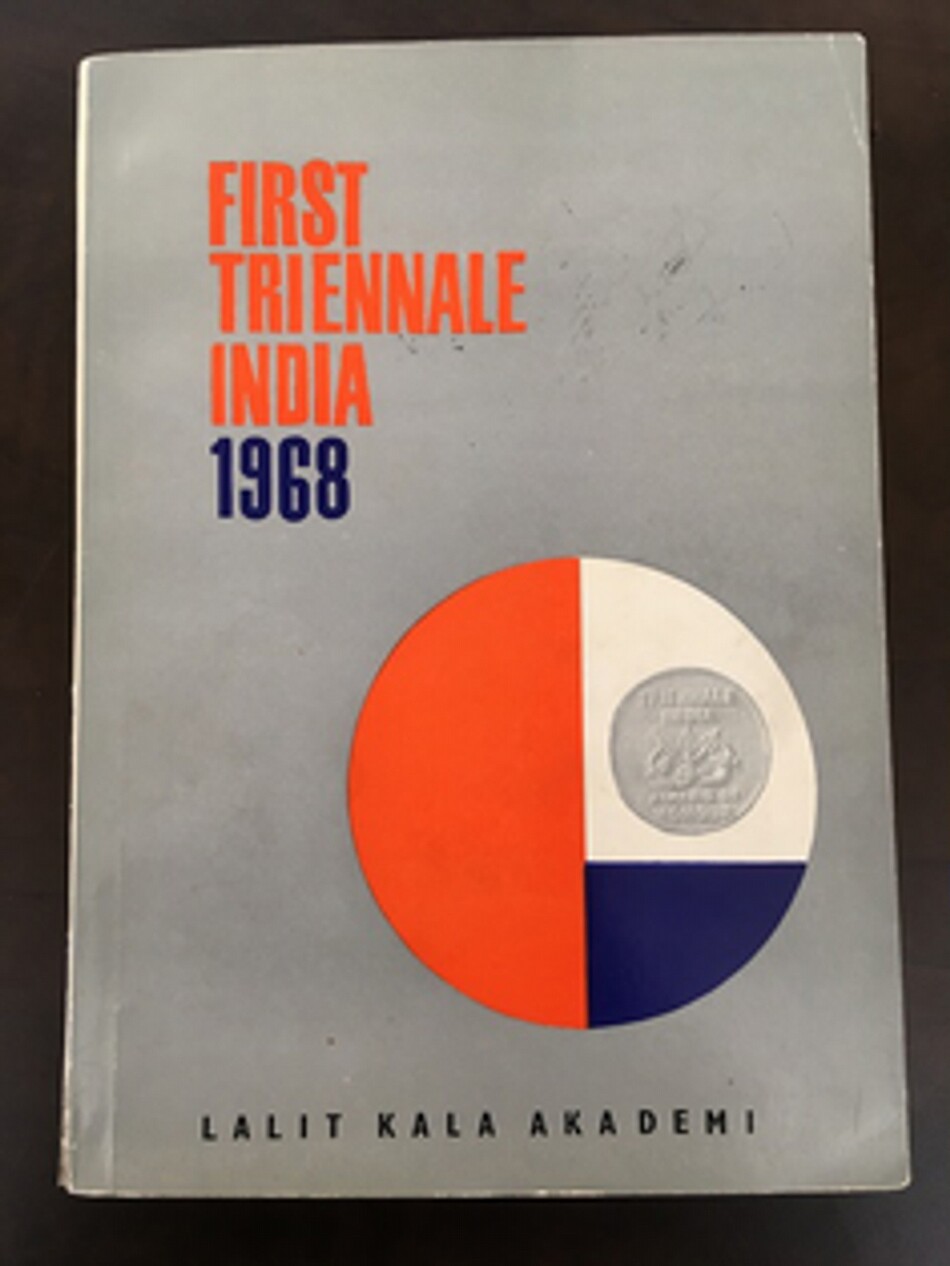

Requiring complex programming in New Delhi and New York City as well as considerable diplomatic backing in its realization, such culture projects as New Delhi’s First Triennale (1968) sought to place India on an expanding world stage of large-scale exhibitions. The Triennale was organized by India’s National Academy of Art, the Lalit Kala Akademi, and featured more than 600 works from 31 countries. This little-discussed Triennale’s format and creation sheds light on the complex aspirations of Indian arts advocates keen on the advancement of the nation through arts, and the tensions inherent to such a project. For while the Lalit Kala Akademi promoted modern arts as a means of advocating for the cultural self-determination of people long under colonial rule, some of its artists patently rejected statist projects to appropriate modern art for the symbolic field of the nation. Decolonization remained in view for such mystical abstractionists as Jagdish Swaminathan (1928–1994), but the perception of decolonization by the 1960s extended well beyond the nationalisms of the early postindependence years. The case studies consider the frictions between varying levels of hegemonic ideologies and counter-hegemonic claims made through modern art in exhibitions in and between both countries. To demystify the mobilization of the nation through internationalist discourses of modern art, or the failure to do so, one must consider the sentiments set to work in planning the nation.

Another case study, a large-scale exhibition organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art and intended for India, Two Decades of American Painting (1967), centers scale as a point of entry into a social history of modernism and its exhibitions. Eliciting controversy, the transportation of the large-scale minimalist and abstract expressionist works in Two Decades required the physical alteration of railcars as well as the use of cargo planes, cranes, trucks, behemoth crates, and the labor of a veritable army of workers. Critically, this exhibition centered the laborers of art—handlers, craters, and others who are largely overlooked by art-historical scholarship despite the key roles they play in enabling art’s presence in exhibition sites. Received as a physical imposition by members of its Indian audience, the scale of the works elicited a critical reception that sheds light on the connected histories of labor, material, and form in the movement of arts and ideas across borders.

As a visiting senior fellow, I looked through selected exhibitions’ art insurance paperwork, art handling and damage reports, curatorial files, diplomatic files, exhibition catalogs, and a range of other curatorial, museological, and bureaucratic documents held at the National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, and Library of Congress.

University of Hartford

Leonard A. Lauder Visiting Senior Fellow, May–June 2024

Rashmi Viswanathan returns to her position as assistant professor of modern and contemporary art at the University of Hartford.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.