Hamed Yousefi

How Modern Art Became Islamic: Imagining God and Man Between Iran’s Two Revolutions

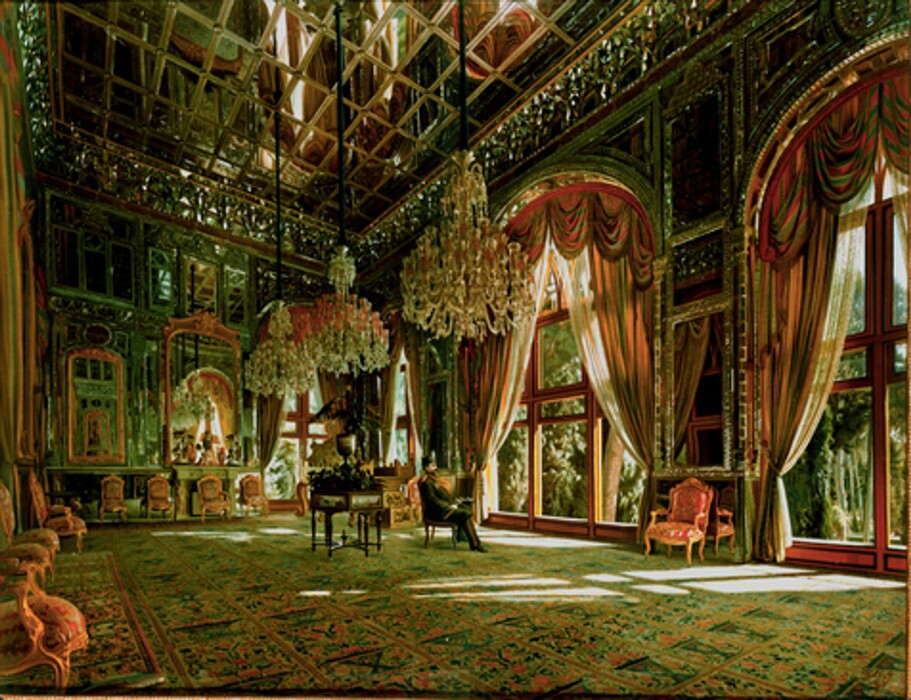

Kamāl al-Mulk, The Hall of Mirrors, 1895, oil on canvas, Gulistan Palace, Tehran. © Gulistan Palace Image Archive

The Center’s Twelve-Month Ittleson Fellowship allowed me to complete my dissertation. Entitled “How Modern Art Became Islamic: Imagining God and Man Between Iran’s Two Revolutions,” this work studies the intersection of modern art and Islamic mysticism (‘irfān), and questions the formative art-historical assumption of the secularity of modern art and its accompanying division of modern and Islamic art in disciplinary periodizations. In this manuscript and in journal articles and book chapters, such as “History or Project? The Double Life of Islamic Art Since the 1970s” (2022) and “Between Illusion and Aspiration: Morteza Avini’s Cinema and Theory of Global Revolution” (2021), I argue that in Iran, the term hunar-i islāmī (Islamic art) was a modern coinage, initially introduced through translations of European art-historical writings and subsequently transformed into a future-oriented project of decolonial imagining. In other words, contrary to art-historical periodizations in Europe and North America, in Iran “Islamic art” was not replaced by modern art. Rather, the two developed in dialogue with one another, charting linked and interdependent paths. My dissertation particularly argues that the intertwining of modernism and Islamic art in Iran compels a properly global art history to engage the Islamic concept of “creative imagination,” or khayāl, among its theories of modern art.

Whereas in the European context, the imagination is commonly understood to be a passive faculty that depends on data from sense perception, in ‘irfān or Islamic mysticism khayāl is conceived as an active faculty shared between God and man, making the imagined as real as reality. Khayāl gives expression, in other words, to distinct forms of factual fiction in artistic production and not only in the contemporary age of “the parafictional,” as Carrie Lambert-Beatty identifies our moment. In 19th- and 20th-century Iran, artistic refashionings of khayāl confronted modernity’s ocular-centric regimes, pitting the reality of the imagined against the rising tide of “objective” representation.

Underscoring the entwinement of pictorial and political representation in encounters between khayāl and modernity, my narrative in “How Modern Art Became Islamic” begins with the 1880s appointment of Constitutionalist Revolutionary and realist painter Kamāl al-Mulk (c. 1863–1940) as the official court artist. I argue that on the eve of the Constitutional Revolution in Iran (1906), Kamāl al-Mulk took optical realism as a European import and imbued it with a particularly Islamic theology. He did so by refashioning khayāl as the private, mental space of an individuated onlooker, which he pictured as the model subject of constitutional citizenship. In The Hall of Mirrors (1895), for example, a near-photographic portrait of the Iranian monarch Nasir al-Din Shah presents the ruler in a moment of repose; both he and the viewer are engaged in parallel acts of solitary observation. In the context of pre-Constitutional uprisings, the painting’s emphasis on optical realism and one-point perspective addresses and anticipates the unity and self-mastery of its viewing subjects. It also underlines the exchangeability of this subject with the sovereign. Yet, nearly half of the picture plane is dedicated to broken mirror reflections. Here, Kamāl al-Mulk takes advantage of the Islamic art of mirror revetment to liberate his painterly marks, and by extension optical realism, from a predetermined relationship with visibilia. Mirror reflections open Kamāl al-Mulk’s picture onto Islamic theologies of the image and imagination, where the mirror functions as an analog for khayāl. In the mirror, as many Muslim authors analogized, a third space emerges between material reality and invisible transcendence, bringing the “other” world into this one. I argue that in The Hall of Mirrors and numerous other paintings of this period, Kamāl al-Mulk utilizes water’s reflective surfaces as well as mirrors to create spaces within realism for khayāl.

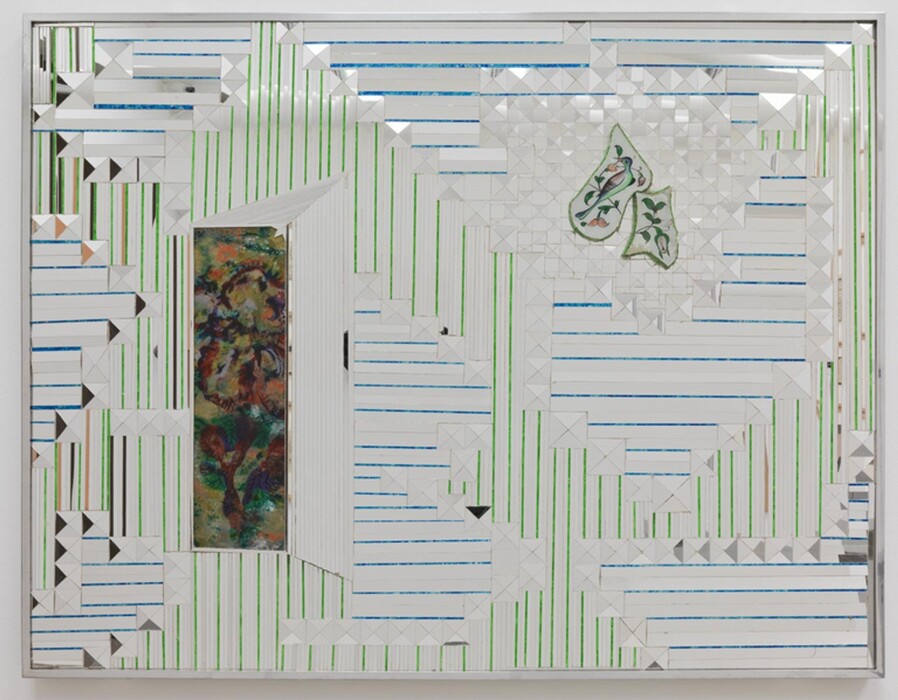

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Something Old Something New, 1974, mirror glass, painted glass, and plaster on wood, Tate Modern

Subsequent chapters of my dissertation follow pivotal moments in what I describe as “a century of khayāl’s modern life”—artistic articulations of khayāl after the institutionalization of optical realism (modernity’s regime of pictorial representation) and parliamentarianism (modernity’s regime of political representation). The Constitutional (1906) and Islamic (1979) Revolutions mark inflection points in how art and Islam were implicated in mutually constitutive processes of political renovation, wherein khayāl became a site of modern subject-making. Kamāl al-Mulk’s paintings of the Constitutional era are contrasted here with mirror reliefs by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian produced in the lead-up to the Islamic Revolution. Here, the experience of viewing the artwork unfolds as the fracturing of the viewing subject into the suspended realm of khayāl, aligning the work with new ideals of political subjectivity beyond representation.

The artists that I study are canonical figures: Kamāl al-Mulk, who introduced European-style painting to Iran; Jalil Ziapour (1920–1999), who is the founding figure of Iranian modernism; and the internationally acclaimed Saqqakhaneh school artists, who are recognized in Europe and North America as pioneers of advanced Iranian art during the 1960s and ’70s. But instead of contributing to the consolidation of a seamless global canon of modern art, these artists pose a challenge to the discipline of art history. My reading of these artists questions the liberal, European conflation of the modern with the secular, unsettles the formative dichotomy in art history between Islamic art (“made in the past”) and the avant-garde (“making the future”), and diversifies the methodological and theoretical frameworks of global modernism. While my work shifts the focus of modern art and its theorization from Europe to the Global (Islamic) South, my conceptualization of khayāl also reveals theosophical and non-secular aspects of mid-20th-century modernism in Europe and North America—the New York School, art informel, pop, minimalism, and conceptual art—by highlighting the contribution of Iranian-born artists to these movements and by elucidating Neoplatonic image theories as a shared point of reference in the global imaginaries of advanced, often oppositional, art.

Northwestern University

Twelve-Month Ittleson Fellow, 2024–2025

In 2025–2026, Hamed Yousefi will be a Klarman Postdoctoral Fellow at Cornell University. The following academic year, he will join the faculty in Art History at Oberlin College & Conservatory.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.