Chaeri Lee

Āsār: Visualizing Vestiges of the Past in 19th-Century Iran

Titled “Āsār: Visualizing Vestiges of Time in 19th-Century Iran,” my dissertation examines 19th-century Iranian engagements with the ancient past through the conceptual lens of the Perso-Arabic term āsār or āthār (آثار, sg. asar اثر). At its core, āsār signifies “traces” or “effects.” Since the early Islamic period (c. eighth to ninth century CE), this term was commonly used to refer to the physical vestiges of pre-Islamic civilizations, which were believed to evidence a preordained divine order culminating in the Day of Judgment.

The term āsār gained renewed resonances in 19th-century Iranian discourses on the pre-Islamic past, which were expressed through a wide array of visual and artistic mediums, such as photography, lithography, pictorial carpets, and lacquer painting. Across four chapters, I demonstrate how this concept, rooted in Islamic philosophical discourses, mediated the convergence of local and foreign scientific, philosophical, and imagistic traditions in 19th-century Iran.

Chapter 1 discusses the renewed valence and transformation of the concept of āsār in the 19th-century Persian and Arabic print landscape. While there was an important divergence between the Arabic and Persian print spheres due to material conditions of the script (that is, lithography for Persian and movable type for Arabic), there was a shared recourse to the conceptual territory of āsār in engagements with ancient monuments.

In 19th-century Iran, as in Europe, photography was widely used as a means of documenting ancient monuments. At the same time, the introduction of photography engendered active debates about the philosophical meaning and implications of visual representation in 19th-century Iran. In Chapter 2, I address how the concept of āsār shaped the rhetoric on photography, as gleaned through late 19th-century technical manuals and treatises. In these writings, photographic images are framed as āsār—both as personal traces and divine effects. I argue that photographic representations of ancient landscapes must be interpreted through an internal philosophical discourse that elevated photography to the level of divinely ordained truth, rather than simply as visual markers of “modernity.”

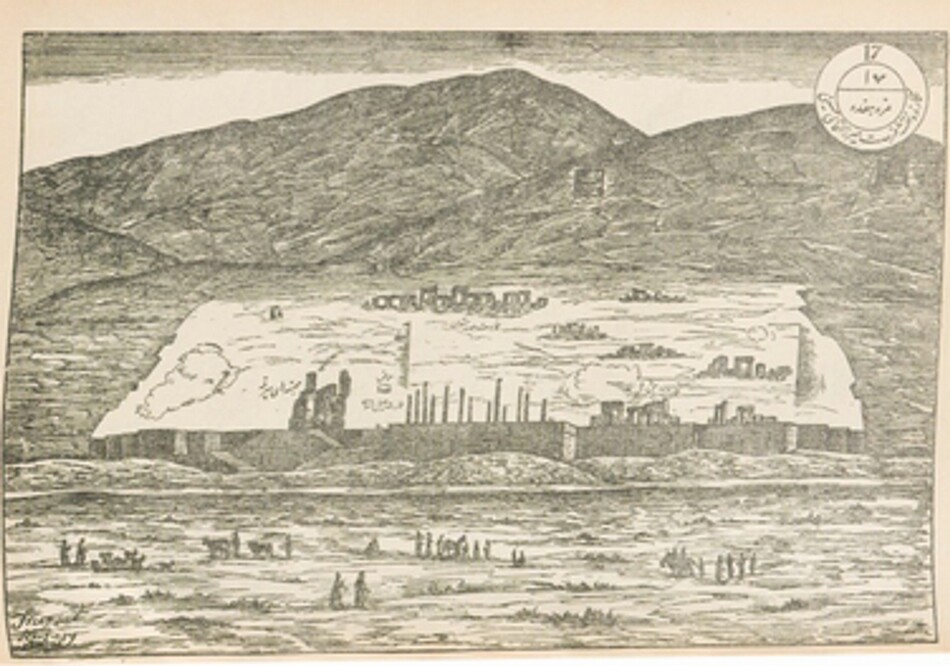

Chapter 3 presents a focused visual and textual analysis of Āsār-i ‘Ajam (1896; Vestiges of Ancient Persia) by the polymath intellectual, artist, and poet Mirza Muhammad Nasir Hosayni Shirazi (also known as Forsat; 1854–1920). Āsār-i ‘Ajam was the first Iranian publication to systematically survey the ancient monuments and ruins of southwestern Iran. It is itself a monumental trace of Forsat’s unique visual, historiographic, and material engagement with the vestiges of the ancient Achaemenid (550–330 BCE) and Sassanian (224–651 CE) dynasties. Throughout the book, Forsat consciously situates his work within the Islamic eschatological and poetic frameworks of āsār, where ancient monuments were understood as physical repositories of historical lessons (‘ibar). The publication also includes 50 lithographic plates after Forsat’s original drawings, which the author describes as works of engineering (muhandisī), signaling that he considered Āsār-i ‘Ajam primarily through a scientific lens of knowledge production.

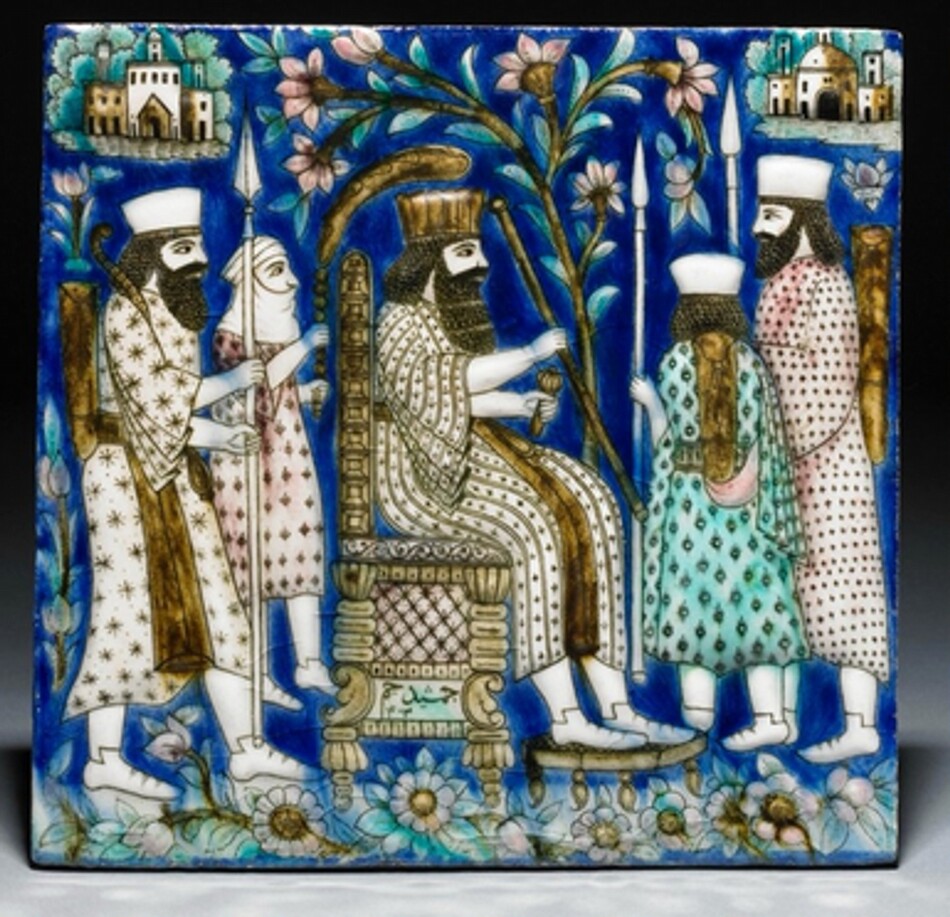

In Āsār-i ‘Ajam, Forsat grapples with historiographic tensions posed by epigraphic discoveries that contradicted established historical narratives espoused by popular texts, such as Firdawsi’s Shahnameh. For instance, Persepolis, long associated with the mytho-historical figure Jamshid, was conspicuously absent in the cuneiform inscriptions deciphered in the mid-19th century. New archaeological discoveries were nevertheless absorbed into mytho-historical narratives that proliferated through traditional artistic mediums—lacquer painting, tilework, metalwork, and figural carpets—the focus of Chapter 4. These transmedial objects attest to the broad resonance of the ancient past in modern Iranian visual culture and underscore the heightened connotations of visual materiality of āsār in 19th-century Iran.

Ultimately, my dissertation reveals that 19th-century Iranian engagements with āsār do not signify a rupture between the Islamic tradition and things often treated as emblematic of secular modernity—history, science, archaeology—but rather demonstrate their complex entanglement. This study thereby enriches our understanding of the intellectual and philosophical history of the modern period through the reintegration of both religiosity and material expression.

Indiana University

Twenty-Four-Month Ittleson Fellow, 2023–2025

Following her PhD defense in late summer 2025, Chaeri Lee will work as a freelance curatorial and academic researcher in Houston.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.