Hamid Keshmirshekan

Retracing Truth: The Haunting Presence of History in Contemporary Art Practices in Iran

Azadeh Akhlaghi, Evin Hills, Tehran, Bijan Jazani 18 April 1975, from the series By an Eyewitness, 2012, digital print on photo paper. Courtesy of the artist

My fellowship at the Center provided me with an opportunity to finalize a chapter in the volume Reinterpreting History and Memory: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), which I am currently editing as part of the series British Academy Proceedings. This volume comprises 14 chapters, and my specific contribution examines how artists, both in Iran and the diaspora, engage with concepts of history and memory to navigate and question the notion of truth. It examines how references to history and memory inevitably constitute an engagement with the interpolation of the present, often with the intention of uncovering truths from both the past and the present. The chapter aims to understand how contemporary art engages with social, cultural, and political issues, offering critical approaches that act as multifaceted tools within resistance aesthetics. I contend that artists articulate their struggle through their works by engaging with themes such as political history and power relations. These works signify a perception of history that is constantly intertwined with our present understanding, echoing John Lukacs’s notion of a “participant history,” in which “our knowledge is not only personal; it is also participatory.”

I adopt a “hauntological” interpretation to read works of art whose recurring references to the past reveal hidden or suppressed stories that continue to shape the present. Just as Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds explain hauntological musicians, contemporary artists explore ideas associated with temporal incoherence, cultural memory, and the persistence of the past. It is through hauntological interpretation that works of art assume a reflexive and critical function by revealing fragments of historical reality that have been inserted in the narrative frames of history.

In my chapter, I show how the concept of hauntology is epitomized in postrevolutionary Iranian art practices, which challenge the notion of a “correct history.” I discuss how contemporary artists from the postrevolution generation navigate and contest an ideologically structured history formulated by the political system, which prioritizes its own ideals while marginalizing alternative perspectives. Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s definition, I use hauntology as a framework to explore narratives, histories, and discourses “haunted” by repressed or forgotten elements of the past. Derrida suggests that hauntology seeks to give voice to these ghostly presences—figures, ideas, or events from the past that have been silenced—to “speak” again. Here, “ghosts” signify repressed histories, ideologies, or unresolved traumas that continue to shape the present.

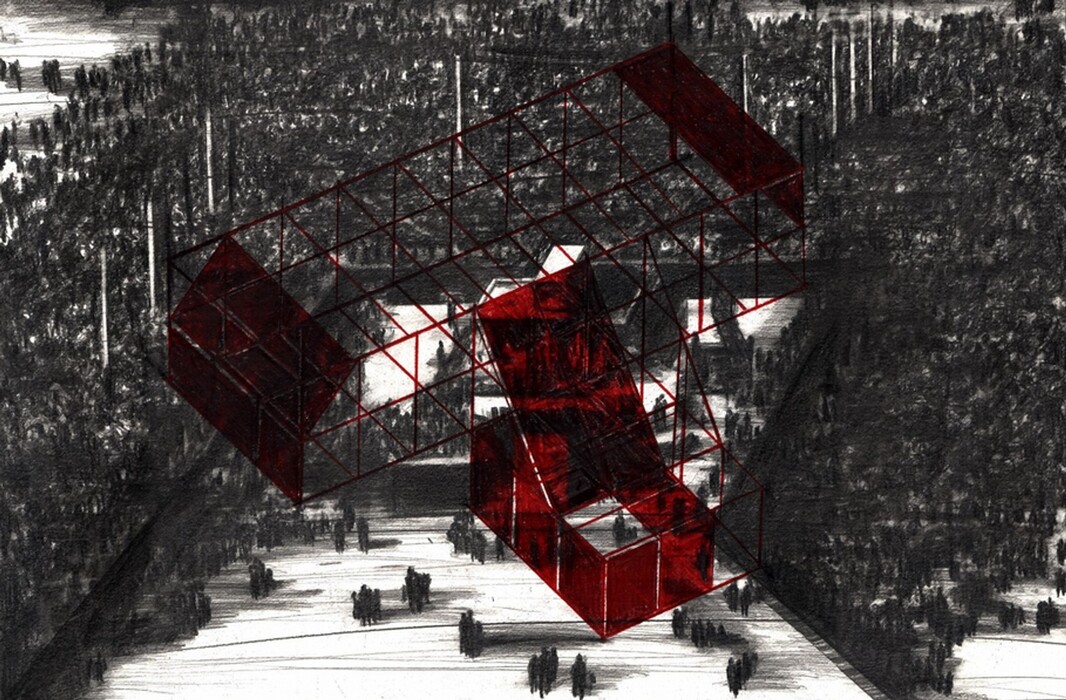

Baktash Sarang Javanbakht, from the series Texture, 2018, pencil on cardboard. Courtesy of the artist

Returning to Lukacs’s concept of participant history, a considerable body of contemporary art practices in Iran function as presentations and dialogues that respond to current times. These works integrate complex pasts into contemporary narratives. This position relates to the ontological questions with which artists engage when addressing their contemporary conditions—namely, critical retellings of a past that continues to haunt the present like a ghost. Meanwhile, the complicated history of postrevolutionary Iran—marked by revolution, war, cultural repression, and recurrent violent suppression of social uprisings—has created a traumatic experience embedded in the collective memory of Iranian society, haunting its present. Artists respond to their own experiences within a context of cultural trauma that permeates the entire society.

To illustrate these concepts further, I will focus on a number of works by artists who belong to the third generation of postrevolutionary Iran. They include photographers Azadeh Akhlaghi (b. 1978; By an Eyewitness series, 2012), Mohammad Ghazali (b. 1980; Persepolis: 2560–2580, 2021) and Parham Taghioff (b. 1978; Asymmetrical Authority, 2018); painters Mehdi Farhadian (b. 1980; Twilight series) and Behrang Samadzadegan (b. 1979; Toward Utopia series); and multimedia artists Baktash Sarang Javanbakht (b. 1981; Texture series) and Nazgol Ansarinia (b. 1979; Pillars series, 2014–2019). These works challenge and deconstruct the dichotomy between historical and contemporary discourses, each offering a distinct practice and a unique perspective on the relationship between history and truth.

The artists whose works are examined in this chapter have not been directly engaged in judgements per se. However, a sense of negotiation might appear from the fact that they refuse to allow invisibility to persevere and obscurity to remain. Their practice of evacuating time and history largely indicates their endeavor to displace the real and change the viewer’s perception of the historical past, fusing it with the present. What unites these artists is their shared encounter with the inevitable ambiguity of the past, which continuously eludes them, leaving them to grapple with their haunted contemporary present.

SOAS, University of London

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, January–February 2025

Hamid Keshmirshekan is integrating the chapter he finalized during his Center fellowship into a forthcoming volume to be published by the British Academy. He is currently a research associate at SOAS, University of London, and a research scholar at Columbia University.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.