Jason Hill

Police Media and Documentary Photography in 20th-Century America

As the Ailsa Mellon Bruce Senior Fellow, I have focused on my ongoing book project on the dynamics of press (and press-adjacent) forms of documentary photography and the technology of police radio, as they worked together to capture and conjure their criminalized subjects and to more broadly shape the public image of policing and criminality in the United States during the 20th century. The project begins with the recognition that news professionals brought modern press photography and other forms of mass-market, commercial, lens-based news media into a state of high technological and operational consolidation at a moment coinciding with the initial deployment of police radio communications systems by law enforcement across the United States, from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Earl R. Blake (photographer), Police rattle, 1936, National Gallery of Art Archives, Index of American Design Records—Object and Renderings Photographs. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Archives

The near-simultaneous outlay of these powerful optical and sonic media regimes unfolded across a common geography, overlaying the police’s radiophonic dragnet with what press historian Gaye Tuchman called the journalist’s “newsnet.” Both newsnet and dragnet concerned the apprehension (if by different means) of a common target in the figure of the criminal. As their champions boasted to anyone who would listen, both press photography and police radio were motivated by the remarkable objective of achieving a near-perfect simultaneity of uncivil disturbance and the capture and arrest (by steel or emulsion) of its agent. Both, too, were predicated on the mythological ethos of technological objectivity, to produce both “news” and “the criminal” as the quasi-scientific manufacture of cutting-edge and newly ubiquitous sensory machines. Willfully beholden to what Eyal Weizman and Matthew Fuller have described as the “logic of the split second” motivating modern policing’s “temporal state of exception”—and what Stuart Hall has characterized as the foreshortened and immediate “actuality time” of press photography—police radio, and the press photography that tracks its beat, swiftly (and all too often irrevocably) designate the persons who are their common quarry as “criminal” prior to any judicial process. Moreover, both of these deeply entangled media operated in a state of deep procedural and structural codependency, with news photographers chasing police signals and police responding to citizens’ fears—fears too often conjured and sanctioned in their racism, classism, and xenophobia by news images in a calamitous, cyclical, trans-institutional reciprocity mapped, albeit without reference to photographs, by Hall and his colleagues in Policing the Crisis (1978).

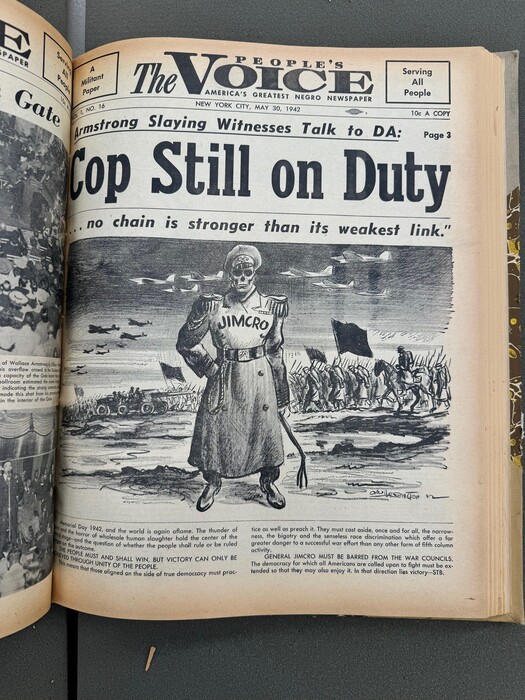

Illustration by Ollie Harrington, The People’s Voice, May 30, 1942, page 1, Library of Congress Photo: Jason Hill

The photographic yield of this entanglement is all too familiar and at the same time all too terrible to show—a wreckage of bludgeoned and detained bodies, mostly poor, mostly Brown and Black people; a million insipid and forgotten inky newsprint snapshots; but also many intelligent and well-intended pictures, also harvested by police radio, by the artful likes of Weegee, Gordon Parks, and Leonard Freed (some held here among the National Gallery’s extraordinary photographic collections). Whoever the maker of these pictures, whether art-historical giants or anonymous and forgotten newsroom staffers, their second-time-around representation now, under the guise of art-historical inquiry, disquiets me too much to deliver here. And so I have, as often than not in my research at the National Gallery, looked to other sorts of things.

While in residence, I have considered many dimensions of this historical and technological conjuncture, its precedents and its aftermaths, all discovered either on-site or at nearby institutions. At the Library of Congress, I have paged through old editions, for example, of Adam Clayton Powell Jr.’s mid-century Harlem newspaper, The People’s Voice. Its reporters privileged the testimony of neighbors over that of police dispatchers, and its crusade against police brutality activated the slower media of cartooning and illustration to counteract the quick, representational violence of cameras at the likes of the New York Daily News. And I have surveyed the photographic archives of The Washington Star (held in the People’s Archive at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, the central location of the DC Public Library system)—archives rich with evidence of that daily newspaper’s photographic obsession with the technologies of police media.

Here at the National Gallery, I have considered the Index of American Design (IAD)’s unexpected concentration of images and research concerning the proto-radiophonic technology of the police rattle, whose noisy racket likewise summoned police and onlookers. Declaring their importance to American craft history, no fewer than four police rattles were discovered, researched, and illustrated by three different artists in three different American cities as part of the IAD’s vast project of historical recuperation into the American “cultural pattern,” undertaken by Holger Cahill and an army of assistants, artists, and photographers during the Works Progress Administration days. Anticipating the operational convergence of police radio and press photography (which coincided with the moment of the IAD), these police rattles (endlessly remediated for greater resonance by photography, watercolor, and finally newspaper halftone) were similarly operative as sonic, optical, and martial technological assemblages, used by citizens as noisemakers to summon police and by police both to spark local illumination (they were used on the colonial night watch to command the lighting of candles) and to bludgeon those deemed by police and fearful citizens to be deviant.

University of Delaware

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Senior Fellow, 2024–2025

In fall 2025, Jason Hill will return to his teaching in the Department of Art History at the University of Delaware.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.