Hugo Shakeshaft

Lifelikeness: A Story of Art in Archaic and Classical Greece

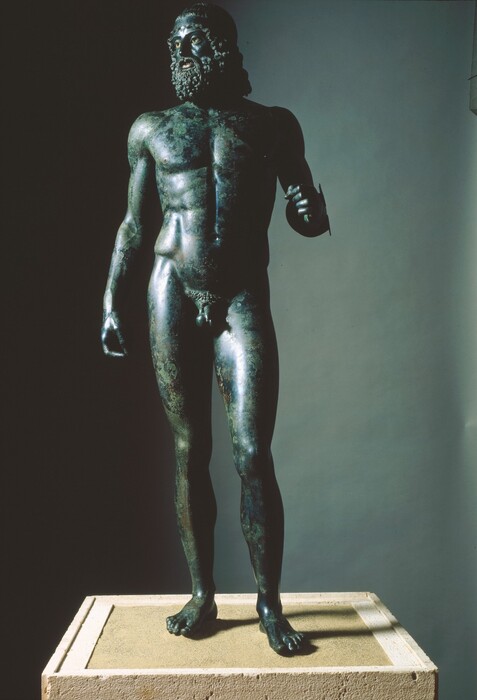

Riace A, c. 460 BCE, bronze, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Reggio Calabria, 12801. Photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

That an image can be “lifelike” is so commonplace that it is easy to overlook how peculiar this statement really is. What does it mean to see and to describe an image as lifelike? On reflection, this apparently anodyne way of talking about images, so often heard in art galleries and online media, reveals itself to be remarkably complex. To call an image lifelike is to identify a strange duality. A lifelike image is by definition not alive. It is lifeless, artificial, an illusion of life. An image must be held to exist in a different way from “real life” in order to qualify as lifelike: it is somehow at a remove from the reality it represents, but is seen to resemble it in certain ways. To see and to describe an image as lifelike, then, is to recognize both its likeness and difference from real life. By the same token, this way of seeing rests on a particular assumption about the nature of images and the relationship between representation and reality. The lifelike image presses at the boundaries between representation and reality, even as it affirms that they are fundamentally separate.

During my fellowship at the Center, I am writing a monograph that delves into an early chapter in the long story of the lifelike image. Fascination with images that look “like living beings” (hōs zōoi), that ostensibly defy their artificiality in their appearance of life, is a golden thread in ancient Greek attitudes to art from the earliest texts of the eighth century through to those of the fifth century BCE and beyond. My book explores the causes and effects of this fascination. Why did lifelikeness matter in ancient Greece and how did it affect Greek art’s development from circa 700 to 400 BCE? I have chosen to concentrate on this period to address a topic at the heart of the Western art-historical tradition. These three centuries witnessed rapid change in Greek art, during which a naturalistic style emerged that oriented the subsequent history of art in the Greco-Roman world. The revival of the naturalistic habits of Greco-Roman art during the Renaissance, and their immense impact thereafter, mean that accounting for the emergence of classical Greek art has a profound bearing on the history of Western art from antiquity to today.

The priest Ka’aper, c. 2465 BCE, sycamore wood, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo, CG 34. Photo: Hugo Shakeshaft

Wonder at lifelike art and stories of images coming to life are deeply embedded in the Western cultural imagination, thanks not least to the heritage of Greco-Roman antiquity. It is easy to assume, therefore, that “praise of the ‘lifelike’ image is,” as W. J. T. Mitchell says, “as old as image-making.” Evidence of artistic values and descriptions of art in the pre-Greek literary records of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant show that this is in fact not true. To claim that lifelikeness is an ideal inherent to image-making is to project Eurocentric values. In the ancient Mediterranean and Near East, explicit praise of the lifelike image is a peculiarly Greek phenomenon until other cultures, notably the Romans, adopted similar ideas through interaction with Hellenic culture. To clarify what gave rise to this attitude to art in Greece, my research interrogates all forms of Greek art through comparison with the artistic traditions of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant.

Though there is no explicit interest in lifelike images in their extant literary records, the Egyptians, Mesopotamians, and Phoenicians all produced naturalistic art long before the Greeks. This observation contradicts a prominent story consistently told by art historians since the 18th century. According to this story, it was the classical Greeks who, for the first time in the history of art, invented naturalism. This fallacy is one among several problematic ideas, many formulated at a time of European imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries, that continues to dominate accounts of the emergence of classical Greek art. While helping to debunk these ideas, my comparative approach highlights the differing ideals and views about the nature of images in the ancient Mediterranean and Near East. As I argued in my opening comments, seeing images as lifelike entails subscribing to a particular view about their nature, which is by no means universally accepted, even among cultures that produced naturalistic art. It turns out that contrary to common opinion, lifelikeness and naturalism are not synonymous. Why this is the case, and what this means for art-historical discourse, is one of the big conceptual stakes of my current research.

A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, 2024–2026

During the forthcoming 2025–2026 academic year, Hugo Shakeshaft will spend the second half of his residency at the Center as the A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.