Julia Silverman

Unmaking Tradition: Native Designers and the Representation of Knowledge During the “Indian New Deal”

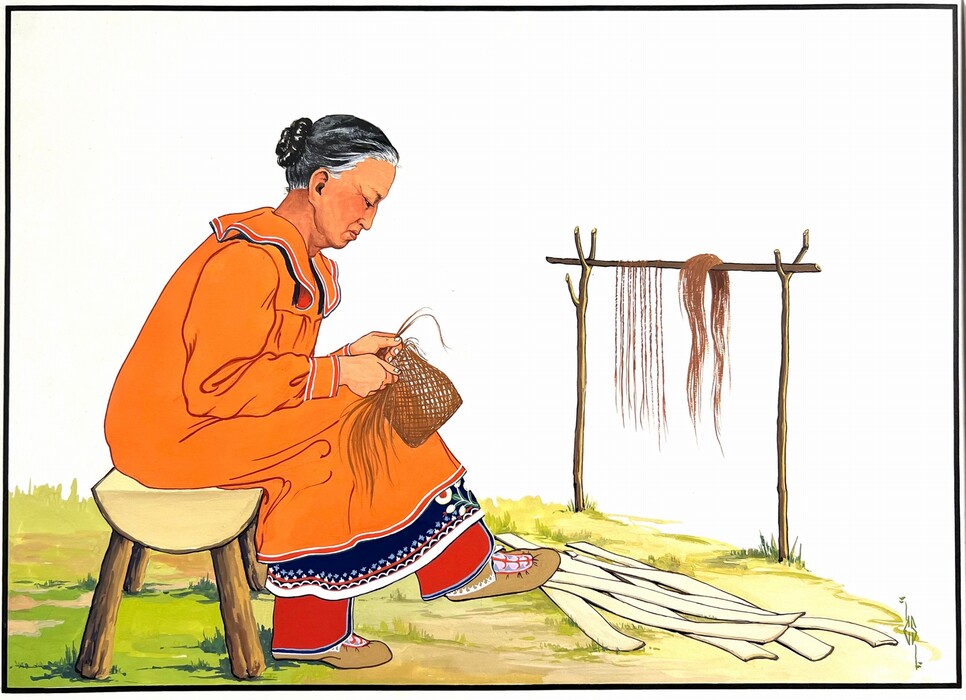

Ernest Smith (Tonawanda Seneca, Heron Clan), The Burden Strap Maker, 1940, watercolor on paper, Courtesy of the Rochester Museum and Science Center, Acc. No. 40.506.1

In 1935 the Rochester Museum of Arts and Sciences hired approximately 100 Hodinöšyö:nih (Seneca) artists to manufacture a new ethnographic collection. Paid by state and federal relief agencies, these artists spent the next six years creating over 5,000 items that cataloged Seneca artistic knowledge and history: beaded and quilled garments, jewelry, furniture, weavings, and wooden carvings, among others. Led by Arthur Caswell Parker (1881–1955), who provided archival photographs and anthropological illustrations for artists to replicate, these artists were able to (re)discover a visual and technical literacy that, by the project’s end, enabled the creation of new Seneca art forms that, while no less “traditional,” might be updated to suit the modern conditions of post-Depression New York.

The Seneca Arts Project, as it’s known today, was but one of several initiatives established during the 1930s that sought to revitalize “traditional” Native American art and craft practices. Bolstered by the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, a reversal of the previous century’s assimilationist policies, and New Deal arts initiatives that aimed to uncover an American “usable past,” such projects variously positioned Native American art—often for the consumption of outsiders—as objects of ethnographic inquiry, marketable commodities, and symbols of a preindustrial American past. Within Native communities, however, artists during this period were experiencing federal investment in cultural practices for the first time in decades. Concepts such as “tradition” or “authenticity,” frequently invoked by non-Native anthropologists and administrators as a metric of cultural purity, took on another meaning as Native artists relearned long-suppressed stories, languages, and artistic techniques. What did it mean, in the 1930s, to “know” a culture? What kinds of knowledge—documentary, haptic, oral—enabled artistic revitalization and continuity? And what implications do these ideas have for ongoing cultural revitalization efforts within Native American nations?

These are but a few of the questions that my dissertation, which I’ve spent two years researching and writing with support from the Center, addresses. Building on work by other scholars that examines New Deal arts projects from the top down, my research returns focus to how Native artists and intellectuals metabolized and reframed these projects’ directives after their implementation. In addition, I explore how Native communities engaged or resisted the anthropological gaze, twisting it to meet emic social and political needs. By combining archival and collections research with conversations with contemporary artists, cultural brokers, and collections stewards, my dissertation attempts to supplement gaps in institutional archival records while also grappling with how art-historical writing might sit in better relation to the histories and epistemologies of descendant communities.

The dissertation is broken into four case studies: The introduction discusses the Index of Indian Design, a proposed but never realized Work Projects Administration initiative that aimed to catalog motifs from arts across Indigenous nations. Using collections and archives from the National Gallery’s Index of American Design, upon which the idea for the Index of Indian Design was premised, I argue for the project not just as a visual archive but as an attempt to record ancestral artistic techniques into reproducible and mobile forms amenable to an age of paper-based bureaucracy. The first chapter, completed during my residence at the Center, treats the Seneca Arts Project. Initially proposed as an effort to replicate the destroyed collection of anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan, the project, I argue, enabled a form of copying that allowed artists to explore the plasticity of “tradition” in Seneca arts. The second chapter looks at the Hopi Silver Project, a 1938 program at the Museum of Northern Arizona to invent a “traditional” style of Hopi jewelry. Adapting forms from basketry, textiles, and pottery, I show how the museum sent Hopi designs into economic circulation, catalyzing a crisis of intellectual property that persists into the present. Meanwhile, I demonstrate that after World War II, Hopi artists Fred Kabotie (1900–1986) and Paul Saufkie (1898–1993) adapted the project into a jewelry course for veterans as a way to reground both people and designs. Finally, I look at the Nome Skin Sewers Cooperative Association, a collective of Iñupiat women commissioned to create performance footwear and parkas for World War II soldiers. I explore how the military commission of these objects as the foremost cold-weather technology—particularly during a period of government investment in chemical synthetic alternatives—might help reframe understandings of craft.

Throughout, the project interrogates how Native peoples engaged their own historical legacies—and ideas about history, more broadly—during the changing political and economic contexts of the 1930s and ’40s, while also questioning how art history might better account for these historical and epistemological forms.

Harvard University

Wyeth Fellow, 2023–2025

With funding from Harvard University, Julia Silverman will complete her dissertation over the 2025–2026 academic year.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.