James H. Miller

Fossils for a Future Time: David Smith and the Sculpting of Traces

“The more a civilization is subjected to the test of time, the more it is reduced to its works of art. The rest rots away,” writes the critic Herbert Read in “Civilization and the Sense of Quality” (1943). By examining the sculptor’s concerns with prehistory, my dissertation explores the responses of David Smith (1906–1965) to what Read called “the survival value of art.” Specifically, it considers the ways Smith analogized his sculptures to fossils—from the Latin fossilis, or “dug up.” Core to my study are his photographs of fossil skeletons—of Triceratops and Protoceratops, of the brain cases of extinct elephants and the jaws of shovel-tusked mastodons—some 40 photographs in all that Smith either captured at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) or specially ordered from its image department. Guided by texts on natural philosophy, paleontology, biology, and genetics, I argue that Smith’s sculpture, in reflecting on extinction, takes on its own status as a trace of what will no longer exist. In doing so, I show how the work’s part-to-whole construction and skeletal linearity matured in connection with this understanding of sculpture as a future-directed trace.

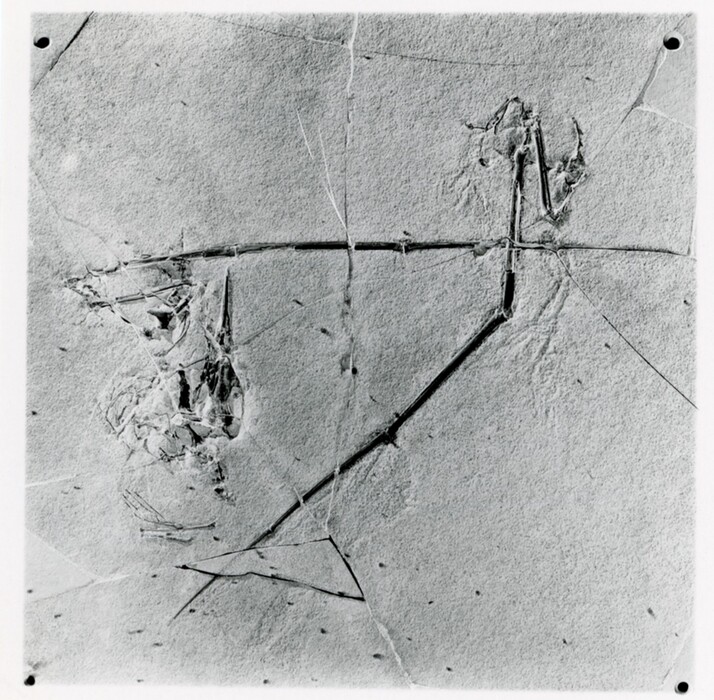

Jurassic Rhamphorhynchus, incomplete skeleton in matrix, David Smith Archives, New York. © 2025 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

During my residency at the Center, my work was divided equally between the project’s beginning and end. In the first chapter, I explain how, in 1987, over two decades after Smith’s fatal car accident, a caretaker of the sculptor’s property in Bolton Landing, New York (now owned by his daughters), unearthed a marble figure. Considering the significance of the find, I introduce Smith’s fossil analogy and explain the character of his natural history as rooted in the idea of burial and excavation. Developing his suggestion that he was radicalized in high school by The Descent of Man (1871), I show that it was this early exposure to Charles Darwin that guided Smith’s responses to Pablo Picasso’s and Julio González’s skeletal, openwork sculpture, reproduced in Cahiers d’Art in the 1920s. Turning to Smith’s time in the Virgin Islands in the early 1930s, I call attention to his early work with shell, bone, and coral. His first documented sculpture, for example, is a piece of eroded polyp skeleton gathered off the beach and mounted to a steel block. After discussing The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842), in which Darwin introduces his theory that coral reefs are stone monuments erected over subsided islands, my chapter argues that the nature of coral explains how Smith came to think about and make sculpture.

Tanktotem IV, Bicycle, 7/29/53, and Taktotem III, all 1953, at Bolton Landing dock, Lake George, New York, c. 1953. Photo: David Smith. © 2025 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In my concluding chapter, I present a fresh approach to Smith’s fabled fields in Bolton Landing, where over 80 sculptures stood outdoors in light and weather, such as the Circles now in the East Building of the National Gallery. I do this in part by reexamining Smith’s practice of staging and photographing his sculptures as creaturely groups in the landscape. Placing these photographs in dialogue with the habitat groups installed in AMNH, I demonstrate how Smith’s emulation of wildlife dioramas extends from a preoccupation with extinction and the “survival value” of sculpture. The taxidermist Carl Akeley, the man behind AMNH’s Hall of African Mammals, for example, desired to create a monument that would “survive, perhaps after much of this animal life has been wiped out.” Similarly, Smith’s photographs ask after sculpture’s meaning in a post-human landscape.

While at the Center, I have paid regular visits to Smith’s stainless-steel Cubi XI on the East Building’s Roof Terrace, keeping notes on how its surfaces are animated by the time of day or time of year. In the “shiftiness” of this late work, I continue to find traces of Smith’s natural history and its recognition of both biological and sculptural flux.

Princeton University

Twenty-Four-Month Chester Dale Fellow, 2023–2025

James H. Miller will return to Princeton University in fall 2025 to complete his dissertation.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.