Alexander Nagel

The Last of the Qataban

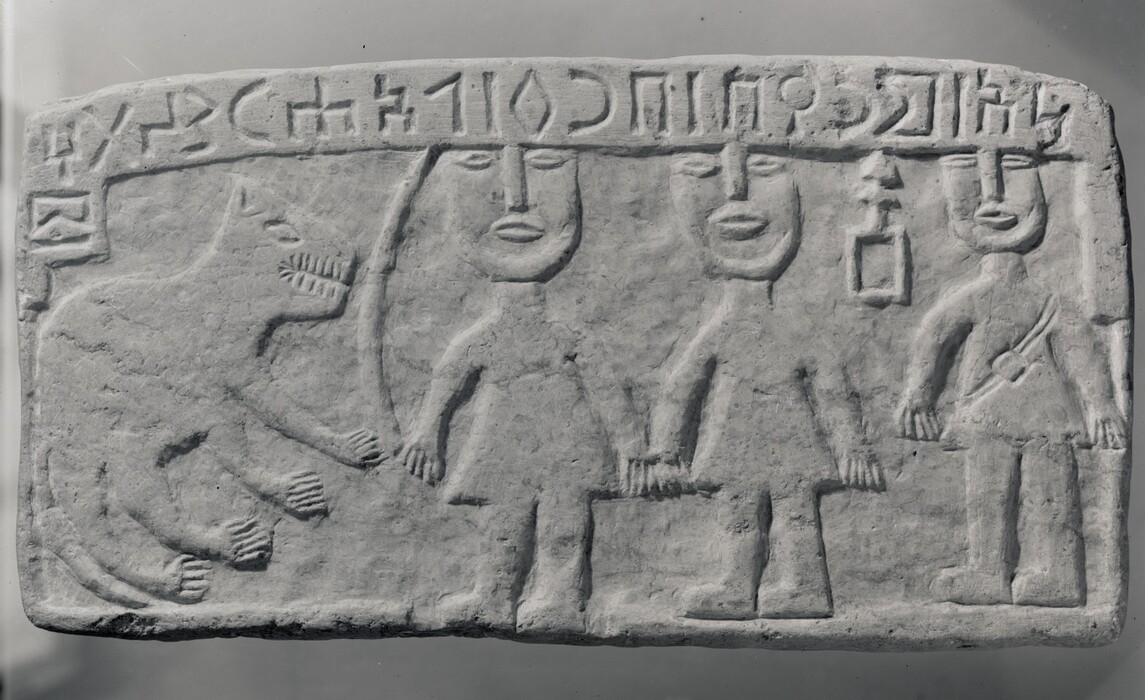

South Arabian plaque, 20th century, alabaster, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum Accession, X.292.1. This object was acquired by the museum from the previous owner, Karl Saben Twitchell (1885–1968), in the late 1920s. The carver also added a modern inscription.

What if Yemenis’ best days are yet to come? During my time at the Center in November and December 2024, I had the opportunity to conduct research and complete revisions on two essays exploring aspects of the intersection of ancient and modern art in Yemen. The core of my project, “The Last of the Qataban,” which began a few years ago, allows me to research modern archives and material repositories of antiquities as I focus on understanding the modern legacies and trajectories of ancient South Arabian art, particularly that produced in the inland Qataban region during the first millennium BCE and first millennium CE. I explore how these ancient artworks, once ungrounded, influenced modern local craft, as well as collectors and museums from Istanbul to Europe and North America.

South Arabian art—encompassing inscriptions, statues, and monuments in a wide range of materials—has often been overlooked by historians compared to more widely studied cultures, such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome. My project aims to fill this gap, with a special emphasis on the role of those who drew inspiration from ancient artifacts discovered in the region. The first documented modern creations date to the 19th century and are kept in museums in London, Berlin, and elsewhere, shelved alongside ancient works of art collected in South Arabia. Craftsmen were clearly inspired by the enthusiasm that entrepreneurs and visitors displayed for the ancient artworks, objects that began to be circulated from South Arabian cities and ports. Artists, particularly those in cities like Aden and Sanaa, began producing alabaster and bronze sculptures that mimicked ancient works of art. These objects were often dismissed as forgeries, but I question this assumption. Were these works imitations, or should they be seen as reinterpretations, reimaginings, or even creative responses to ancient materials? I explore the intent behind these works, examining whether they represent new forms of contemporary art or deliberate misrepresentations of ancient art.

South Arabian plaque, 20th century, Vorderasiatisches Museum, VA 08972. This object was acquired from the collection of researcher Carl Rathjens (1887–1966) in the early 1930s. The carver also added a modern inscription.

A significant portion of my research relied on archival sources, especially the papers of those who worked in Yemen, including Carl Rathjens (1887–1966), Gus Van Beek (1922–2012), and Albert Jamme (1916–2004), as well as dealer and collector records providing provenance information. I was especially interested in the information related to artworks currently housed in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, where I have been a research associate with the National Museum of Natural History since 2013. I also had the privilege of exploring documents in other archives, including the extensive collections of curators and staff at the Vorderasiatische Museum and Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin as well as those of mining engineer Karl Saben Twitchell (1885–1968) in Princeton, collectors Herbert Cahn (1915–2002) and André Emmerich (1924–2007), and James Swauger (1913–2005) in Pittsburgh.

Both the Aden-based merchant Kaiky Muncherjee (1873–1955) and Sanaa-based Israel Subairy (1900–1968) emerge as key figures in the distribution of modern materials. A 1933 letter by the German scholar Hans Schlobies, preserved in the Rathjens Archives of the Staatsbibliothek Hamburg, notes: “There was still a lot of archaeological and epigraphic material to be found here in Sanaa. New goods are constantly appearing, although the antiquities trade has noticeably reduced in size because of the crisis. A new species of falsifications is interesting. You must admire the imagination of the manufacturers! Your friend I. Sub. is one of the main organizers of the business, in my opinion, he is a crook of a fairly modest stature who works with fairly primitive tricks” (my translation).

Examining the intellectual context in which these artifacts moved, and considering the roles of diplomats, dealers, and other intermediaries who facilitated the shipment of these materials from South Arabia helps us to understand the motivations behind and implications of these movements. It also allows us to uncover the cultural exchange that occurred between Aden, Sanaa, and the wider world during the early 20th century. Despite the violence Yemenis have faced in recent years, which has had a devastating impact on the region’s heritage and artistic traditions, Yemeni artists continue to demonstrate resilience. Their creative responses challenge European and North American narratives and preserve their artistic identity in the face of adversity. My residency at the Center allowed me time to reflect. Moving forward, I am both advocating for a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of how Yemeni artists have engaged with their ancient heritage and arguing for the recognition and appreciation of these contributions in the broader discussion of art, culture, and history.

Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, November–December 2024

Alexander Nagel will return to his position as chair of the Art History and Museum Professions program at the Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.