Paul Niell

The Bohío and the City: Ephemeral Architecture and Urbanism in the Late Spanish Colonial Caribbean

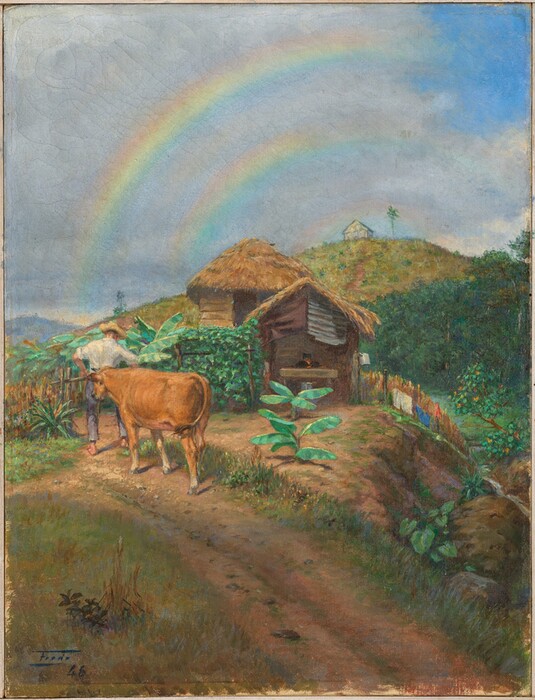

Ramón Frade, Paisaje Campestre (Country Landscape), 1946, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Rafael and Maria Garces in honor of Ubaldo and Ines Soto, 2021.90

While imposing fortresses and grand churches often dominate narratives of Caribbean colonial architecture, a far more ubiquitous yet frequently overlooked structure, the thatched bohío, is often tucked into the scholarly shadows. Yet, this form of building played a vital role in shaping the region’s urban and social fabric. The Smithsonian American Art Museum preserves a painting from 1946 by Puerto Rican artist Ramón Frade (1875–1954), titled Paisaje Campestre (Country Landscape). This seemingly idyllic scene depicts a male figure and his oxen walking along a dirt path toward his wooden and palm-thatched home, nestled among cultivated gardens and rolling hillsides, beneath an iridescent rainbow. The house and property deftly convey the realm of the campesino, the self-sufficient country dweller in the Puerto Rican hinterland, embodying a rugged but autonomous life lived close to the land. However, this pastoral view belies a more complex reality. Thatched buildings, or bohíos as they are widely known in the Caribbean, were once a common sight in both bustling towns and the quiet countryside, plunging us into a long-established and complex discourse in the islands of Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, and Cuba about the very essence of place and identity. Too frequently, scholars relegate these structures to the realm of vernacular architecture, contrasting them with a “monumental” landscape of historical forts, churches, and civic buildings—the very architectural tools of colonial power. Celebrated for their endurance as symbols of national patrimony, these sturdy monuments, beneficiaries of sophisticated conservation, underscore the relative ephemerality of thatch-covered dwellings, which have long been consigned in Caribbean cultural expressions to a vanishing Creole countryside.

View of the Town of Aibonito, c. 1898–1899, photograph, from José de Olivares, Our Islands and Their People as Seen with Camera and Pencil (Saint Louis and New York: N. D. Thompson Publishing, 1899), 2:406

Contrary to narratives that relegate these structures to the margins of Caribbean history, by the late 19th century it is estimated that over half the population of Puerto Rico alone lived under thatched roofs. However, the histories of these bohíos are riddled with essentialisms that solely associate them with rural poverty or a premodern past, thus lacking dedicated research and theorization. This unfortunate neglect means that we miss crucial material histories, particularly those of Indigenous and African descendants whose daily lives and contributions were intimately tied to such dwellings, consequently obscuring vital chapters in the region’s past. The urban life intrinsically linked to these buildings has been especially forgotten.

The imperialist publication Our Islands and Their People as Seen with Camera and Pencil from 1899 provides invaluable visual insights into the daily lives of urban Puerto Rican bohío dwellers, often absent from maps, plans, and archival documents. A photograph of Aibonito, in Puerto Rico’s mountainous interior, captured from the vantage point of a nearby barracks roof, offers a sweeping view of what the caption describes as a “class of houses in the suburbs occupied by the peons and laboring people.” Yet, beyond this potentially objectifying description, the image reveals a dynamic community. Residents, including young boys on a path and women carrying goods, meet the camera’s gaze. In the background, bohíos, elevated on stilts and thatched with yaguas (strips of palm bark), are clearly integrated into the pueblo, evidenced by signs of daily life such as laundry lines and animal enclosures. The pathways connecting these dwellings to the city center suggest the extent to which the urban core and these outlying communities interacted. As the scholar Lisa Goff, examining 19th-century shantytowns in the United States, has shown, the act of dwelling by the working poor represents a way of adapting and reshaping the urban landscape.

During my residency, I have been developing a book on this topic, which consists of a series of chapters that focus on what I see as the most important critical issues that arise when we center the relation between the bohío and the city in the late Spanish colonial Caribbean (1762–1898). In most cases, such buildings no longer survive, necessitating the careful use of documentary collections. To this end, I have conducted research in the National Gallery’s rich holdings of image collections and rare books. I have also consulted several Library of Congress divisions; the archival and object collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and National Museum of Natural History; the National Archives Still Picture Branch; and the rare books collections of both Dumbarton Oaks and the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Florida State University

Samuel H. Kress Senior Fellow, 2024–2025

In the coming year, Paul Niell will be conducting archival, on-site, and ethnographic research in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. In addition, he will continue to process the rich evidence uncovered from collections of the Washington, DC, area.

Research Reports

Dive into the research of this year’s cohort of 40+ fellows and interns.