Creating an Index of American Design

Index Artists at Work – New York City, 1938. Index of American Design Records, Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Archives

Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Archives.

On this Page:

In the 1930s and early ’40s, the United States took on one of its most ambitious art projects. To create the Index of American Design, well over 1,000 artists made more than 18,000 meticulous drawings of objects.

The types of objects varied widely, from altars, andirons, and ammunition bags to whirligigs, wrenches, writing desks, and yokes. They came from homes, museums, churches, and antique stores in cities and states across the country. The Index was intended to identify and preserve a uniquely American aesthetic—and to inspire contemporary design.

The Index project was a national enterprise that employed a diverse group of people during the Great Depression. It was a division of the Federal Art Project (FAP) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Headquartered in Washington, DC, the Index of American Design included 37 offices in 34 states and DC.

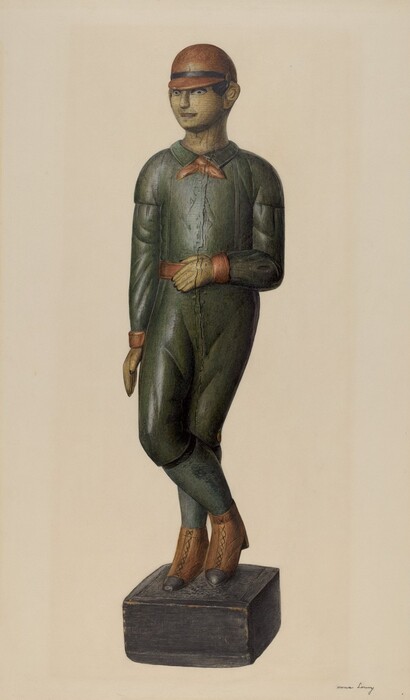

Artist Mina Lowry spent five years working on the Index. This watercolor shows a wooden baseball player figure owned by filmmaker Jay Leyda.

Mina Lowry, Baseball Player, 1935/1942, watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on paperboard, Index of American Design, 1943.8.16410

But the Index was an uneven vision of the United States. It aimed to produce a shared identity through decorative arts. It was also a “kind of archaeology,” according to FAP director Holger Cahill. At the same time, it largely excluded, intentionally or by oversight, Indigenous, African American, and Asian American objects. Cahill described the subject of the Index as the “practical, popular and folk arts of the peoples of European origin who created the material culture of this country.”

Origins of the Index

The idea for the Index was hatched by an artist and a librarian. In 1935, textile designer Ruth Reeves came to Romana Javitz, a librarian at the New York Public Library, with a problem. Reeves was motivated by the communities that made and used traditional crafts, but she struggled to find the reproductions she wanted to see.

Javitz agreed. In a 1965 interview, Javitz described being able to easily find pictures of elaborate European evening gowns but not of what she considered a typical American sunbonnet. The two wanted to fill this gap, and a plan for the Index quickly emerged.

Reeves proposed the Index project to officials in DC and New York and was appointed national coordinator of the Index. She, alongside state administrators, began the work of employing hundreds of artists and researchers

Classified among “practical arts,” the Index is featured in this infographic for the Federal Art Project and Works Progress Administration. As of July 1, 1936, the Index employed 393 people. Illustration reproduced in Art for the Millions (ed. Francis O’Connor, 1973), p. 40.

Index Objects and How They Were Depicted

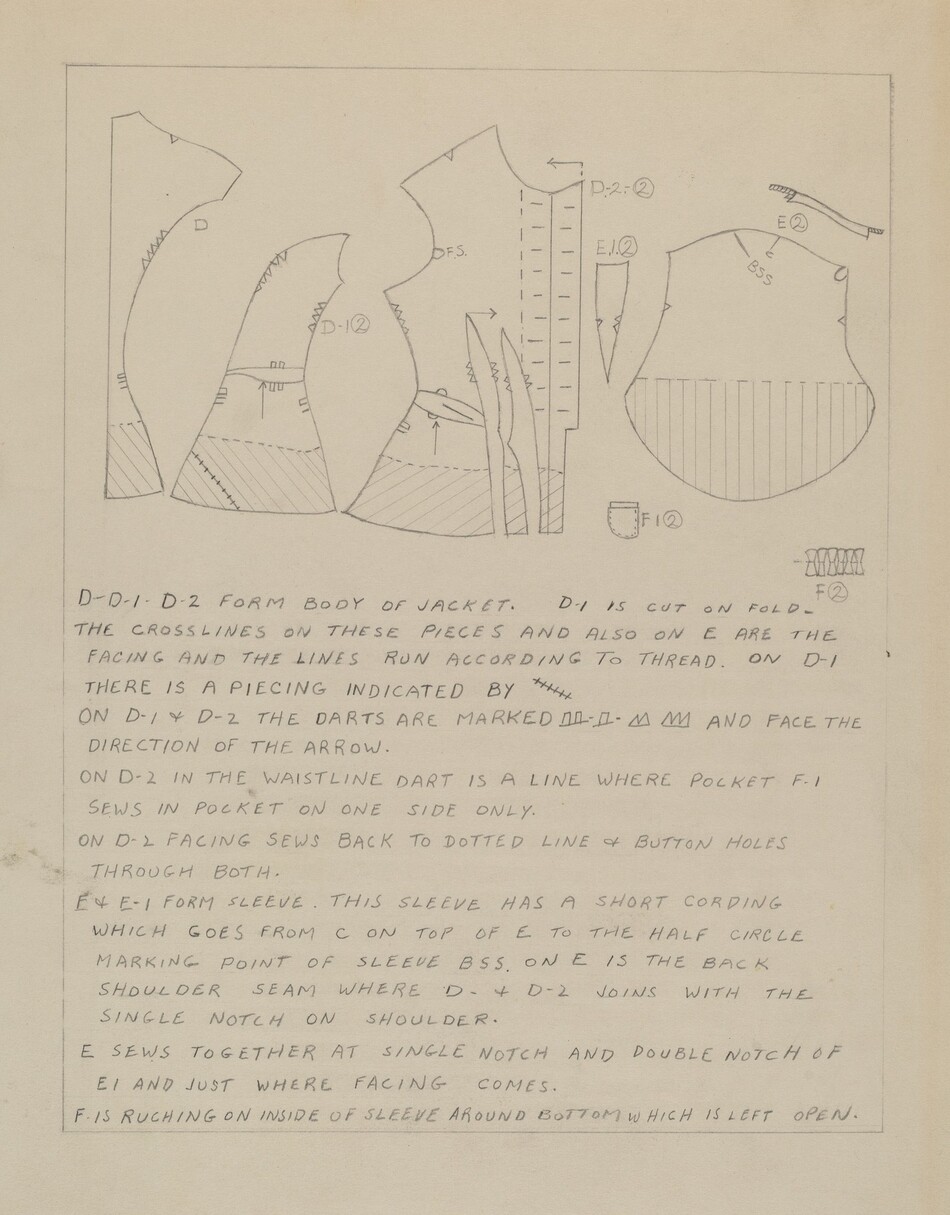

The process of selecting and depicting objects for the Index was not always straightforward. In a 1964 interview, project administrator Phyllis Crawford recalled DC staff quarreling over what items to feature and how to draw them.

Following European models of encyclopedic design books, objects were intended to be organized into “portfolios”—large-format catalogs filled with prints. Before an artist began working, a researcher filled out a data report sheet for each object. The National Gallery Archives hold over 20,000 such reports, which list information such as object owners and original makers.

Proposed classes of objects included homespun textiles, silver, stoneware, lighting devices, and wood carvings. Objects were also categorized by the groups of people that produced them: Shaker and Pennsylvania-German crafts, New England embroideries, Connecticut furniture, and “Spanish-Colonial arts.” WPA press releases and public relations campaigns encouraged private citizens to open their homes to Index researchers, artists, and photographers.

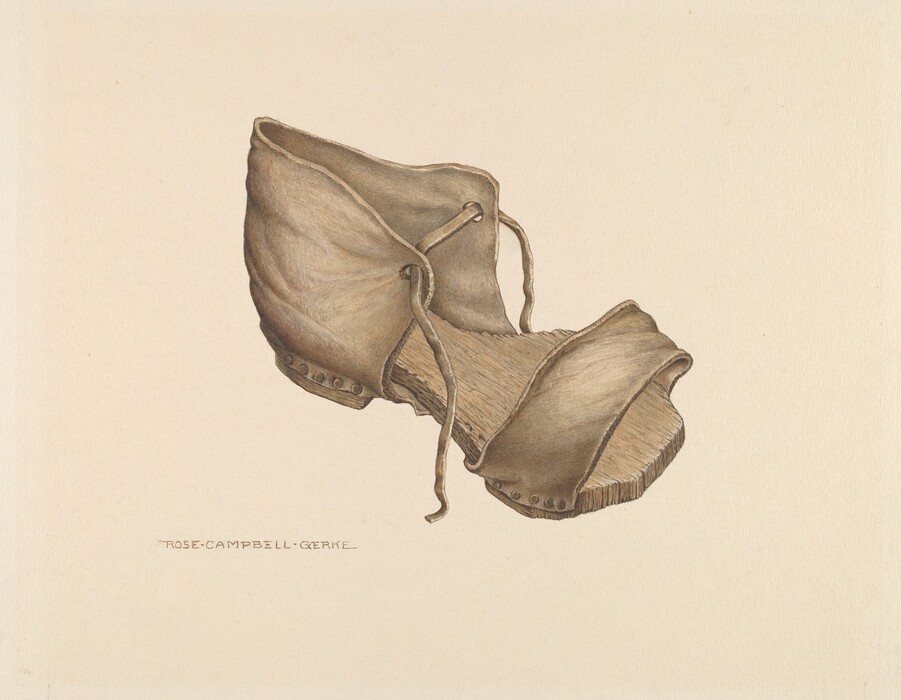

In California artists made hundreds of drawings of early Spanish colonial objects and architecture. Artist Rose Campbell-Gerke painted this leather shoe in 1940. The shoe, reported to have been made by Juan Onessimo, was found while remodeling a house in Monterey built in 1828.

Rose Campbell-Gerke, Leather Shoe, c. 1940, watercolor and graphite on paperboard, Index of American Design, 1943.8.1966

Painting by hand, the artists sometimes used photographs as guides. This technique mimicked direct observation while embellishing details like surface texture and signs of use. Although watercolor drawings were the main output, some Index units hired only photographers to document objects. A trove of these photographs are also in National Gallery Archives.

Artists sent their finished renderings to DC, where administrators determined whether they met Index standards. Administrators rejected watercolors that they felt that were not accurate representations of objects or of design categories. The artists were then asked to start again.

Index of American Design promotional stories were circulated in American newspapers. This archival photograph from a piece called “Garret to Gallery” shows artists at work in a project studio. Index of American Design Records, Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Archives.

Index of American Design promotional stories were circulated in American newspapers. This archival photograph from a piece called “Garret to Gallery” shows artists at work in a project studio. Index of American Design Records, Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Archives.

An Index Belonging to the American People

Although the Index was widely admired, its funding, along with that of other FAP projects, was cut in 1939. And in 1942, the federal government reallocated resources to war efforts. The Index portfolios had been intended for distribution to schools, museums, and libraries across the United States. But the project remained incomplete, with around half of the planned number of drawings created.

After the end of the FAP, the Index needed a home. There was some tension between the interest in publishing the Index portfolios and a desire to exhibit the watercolors. The collection was first loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Index drawings were also exhibited widely across the nation, from community art centers to major department stores. One preliminary agreement promised the collection to the Library of Congress.

The Index was finally promised to the National Gallery in 1943. Philip B. Fleming, administrator of the FWA, said that if any labor of art and scholarship ever belonged to the American people it was the Index of American Design. The Index drawings now comprise around 12 percent of the total works in the National Gallery’s collection.

The Index, Nearly a Century Later

Today the Index is a lens through which contemporary artists reflect on shared visions and values. Artists and students still use the Index framework today.

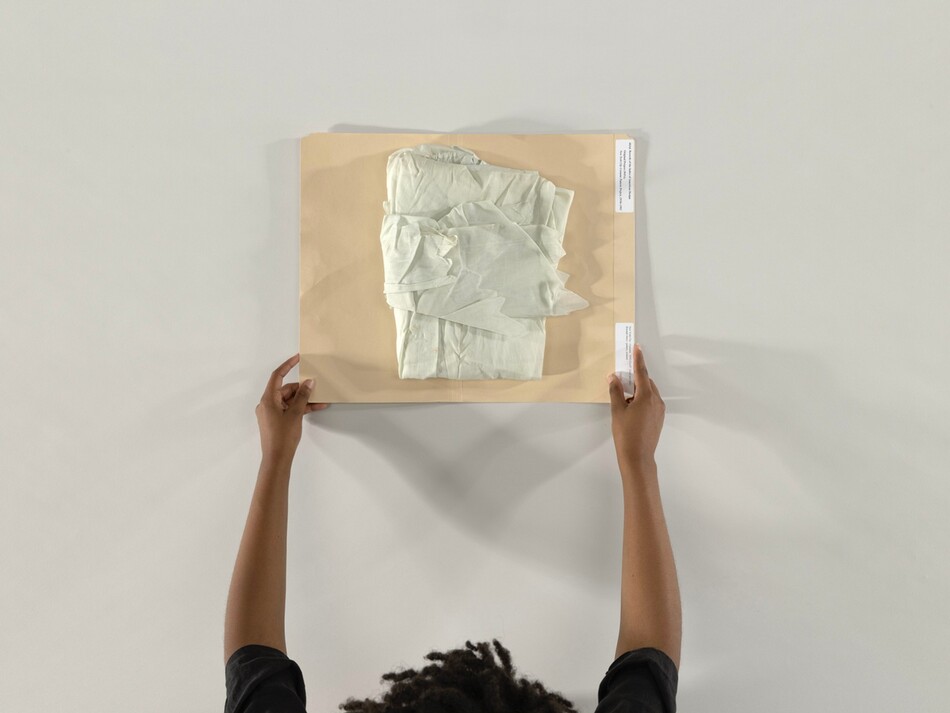

For costume and textile designers, the Index can be both inspiration and raw data. Howard University fashion design student Kennedy R. Martin explored a unique collection of 36 fabric costume patterns. Martin first worked with National Gallery conservation staff to unfold and photograph the patterns, some of which comprised dozens of works. She then used these patterns to make new designs.

Artist Kara Braciale grounds her art practice in expanding the Index. Her students at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design depict objects using the drawing techniques of Index artists. They also write down information about those objects, inspired by the data sheets Romana Javitz designed. By making records of tangible materials, Braciale’s classes reflect on what it takes to reimagine an heirloom for future generations.

You may also like

Article: Seven Highlights from the Index of American Design

Peer into the American past with a collection of Great Depression–era watercolors.

Article: Dressing for Dinner in the Gilded Age

This 19th-century dinner dress captured in the Index of American Design gives us a glimpse of how the wealthy dressed for dinner.