Seven Highlights from the Index of American Design

The paintings in Index of American Design depict a dizzying variety of objects: weathervanes, knives, mantel clocks, bonnets, cradles, ship figureheads, cake molds, and wedding corsets—to name a few. These paintings are a chronicle of American folk, decorative, and industrial objects from the 18th and 19th centuries. Documenting a time before mass manufacturing and mail-order catalogs, the Index artists depicted hand-crafted, regionally distinctive objects.

The Index was a Works Progress Administration project started in 1936, during the Great Depression. It employed over 1,000 out-of-work artists across 34 states—and even more administrators and researchers. The project ran until 1942, and in that time the artists produced over 18,000 watercolors. The National Gallery acquired this collection of their meticulously rendered watercolors in 1943.

Learn about the Index through seven highlights and meet some of the artists who made the project their own.

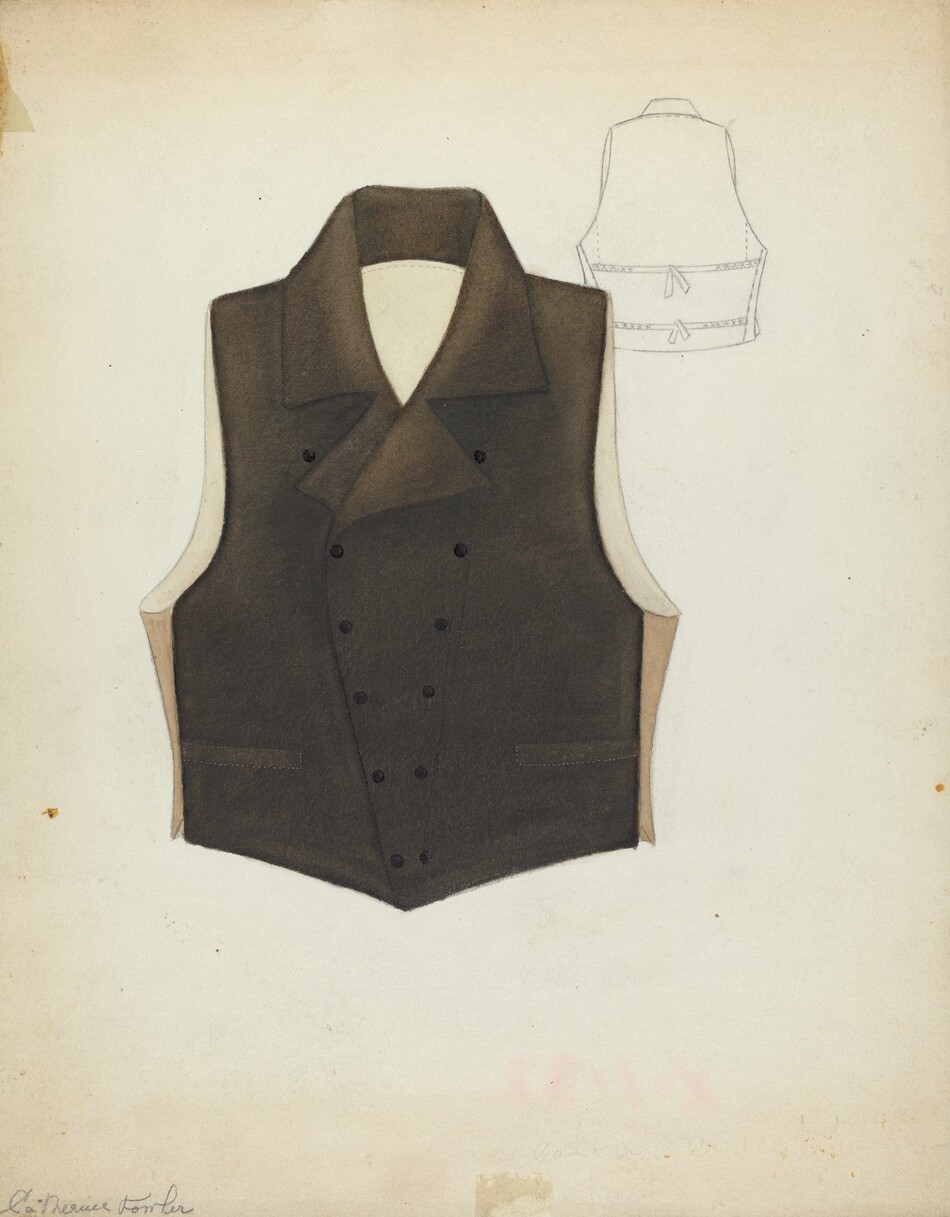

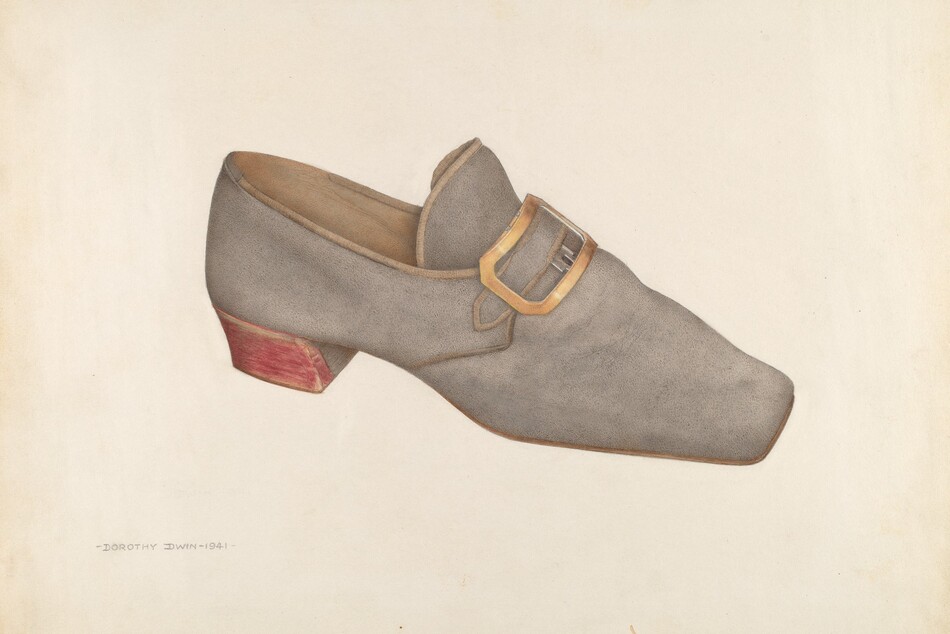

1. Costumes from New York City

The Index project had an office specifically for New York City—and that office was prolific. It contributed over 5,000 of the renderings now in our collection, far more than any other office. One of its focuses was “costumes”: clothing that American adults and children had worn between the late 18th and 19th centuries. These costumes range from formal gowns with luxurious fabrics and intricate pleats to simple cotton nightgowns. We can explore what women of the period would have worn to her weddings or a man’s work shirt. We can find a fireman’s uniform or a woman’s ‘gym suit’ (a full body garment which includes a flannel cape). These renderings of costumes, like the rest of the Index renderings, show us how people from the 18th and 19th centuries lived their lives: how they celebrated important moments and how they experienced mundane ones.

Many of the costumes depicted belonged to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In fact, the founders and early administrators of what we now know as the Met’s Costume Institute, the institution funded by the annual Met Gala, were involved in the Index project.

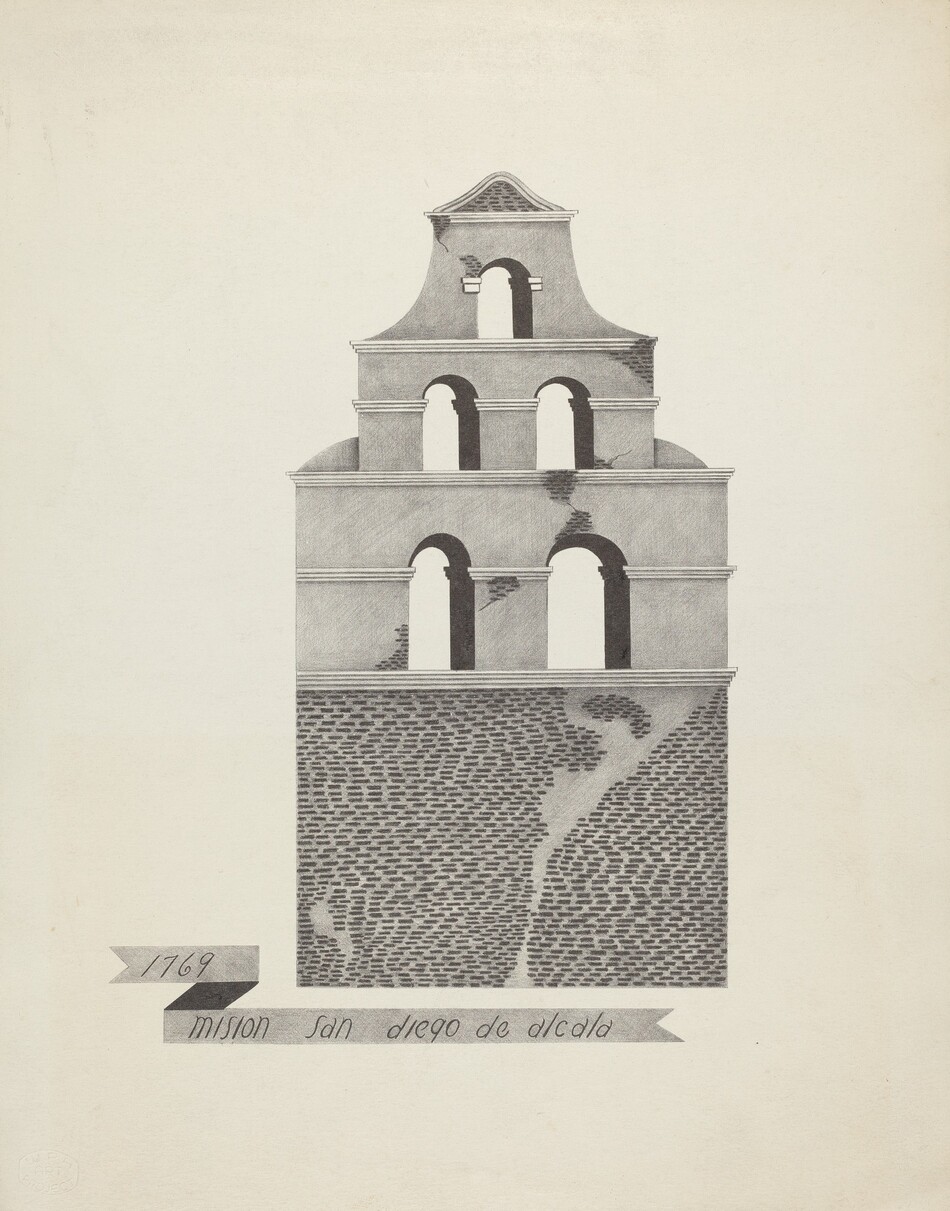

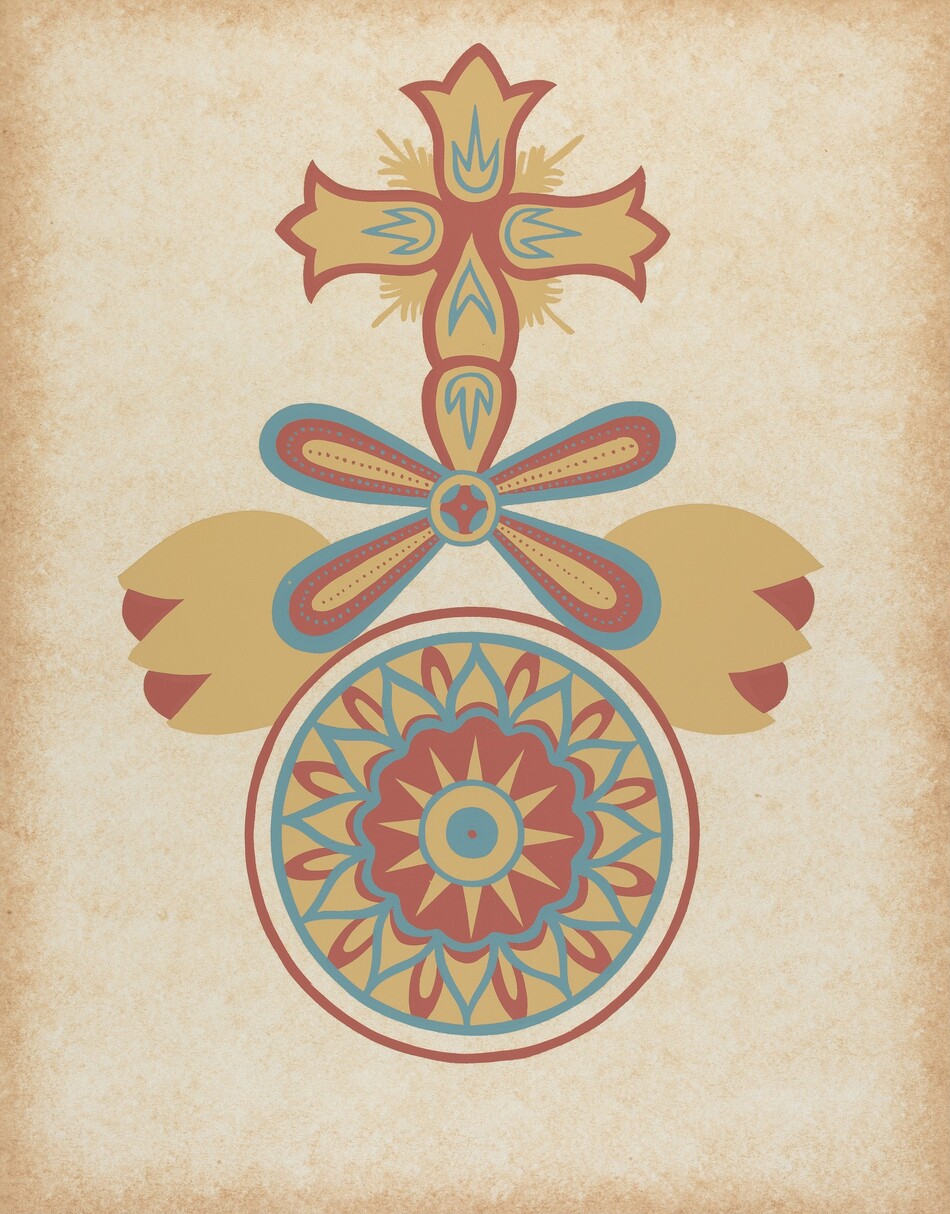

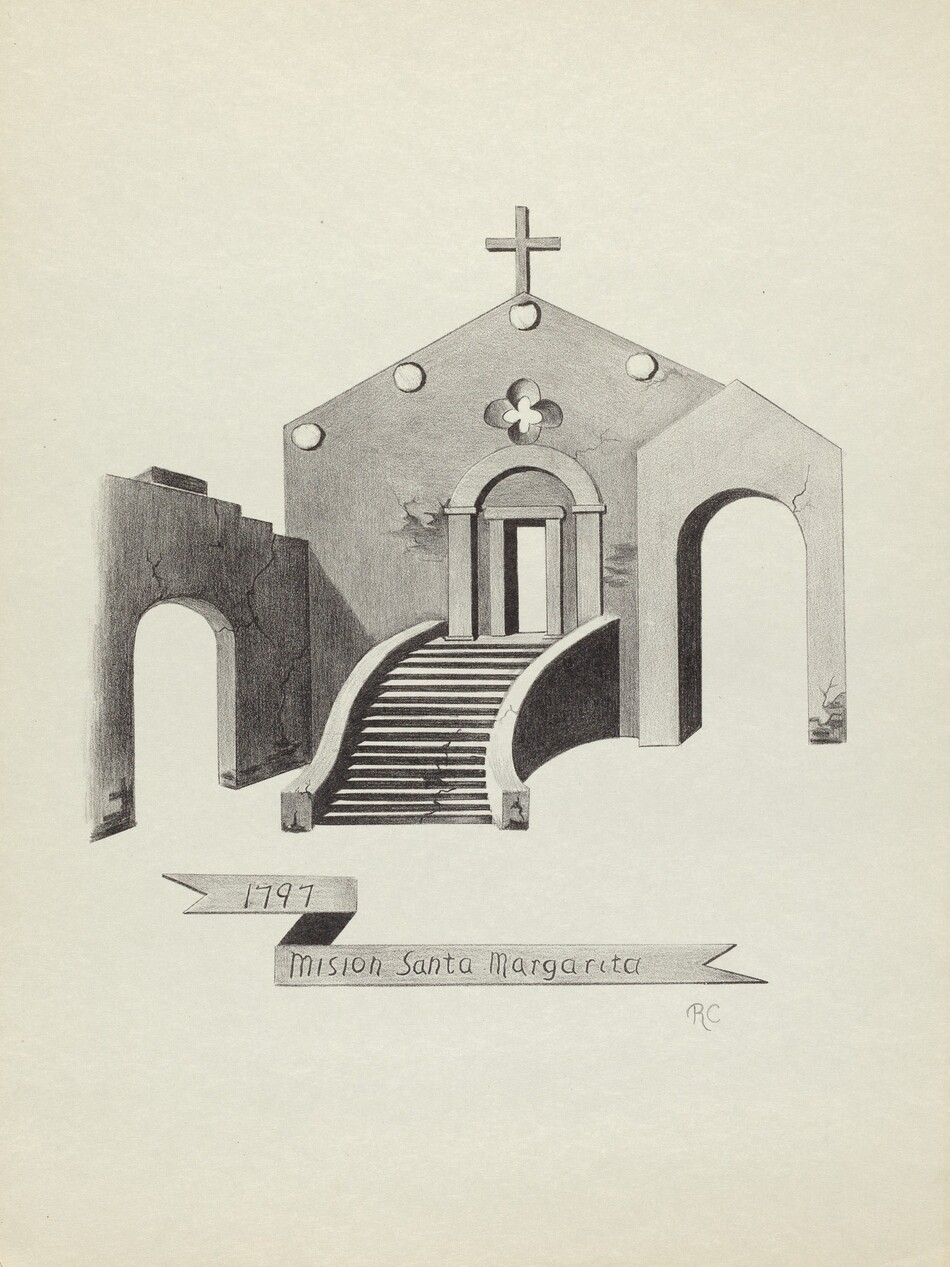

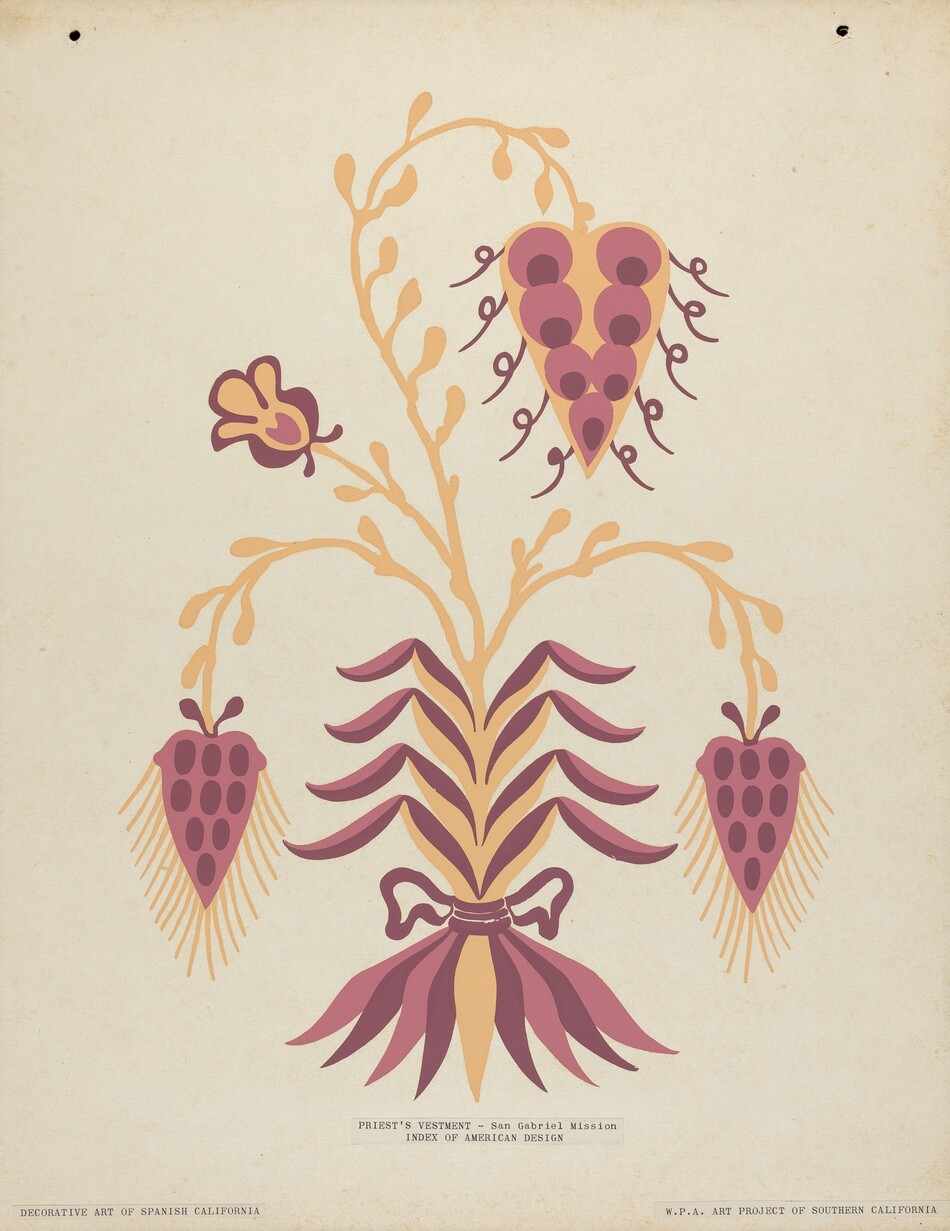

2. Spanish Missions in the Southwest

One of the major focuses of the Index’s Southern California office was Spanish Missions. By the 1930s, these relics of Spain’s colonial presence in California were considered historic sites. Artist James Jones made incredibly detailed, black-and-white renderings of these mission buildings, capturing their architectural style and condition.

Index artists also documented the decorative features of the architecture or of objects inside the buildings—wall paintings, altar tabernacles, or priests’ garments. Many of these renderings capture the vibrant colors of this decoration, with stunning teal and coral hues faithfully replicated.

We can also see how, at the time these renderings were made, many of the mission buildings had fallen into disrepair, with cracks pictured in their stone walls. The artists of the Index sought to chronicle these buildings so that, despite whatever further deterioration occurred, a record of them would exist. Today these renderings serve as historical records for these buildings, many of which have since been renovated.

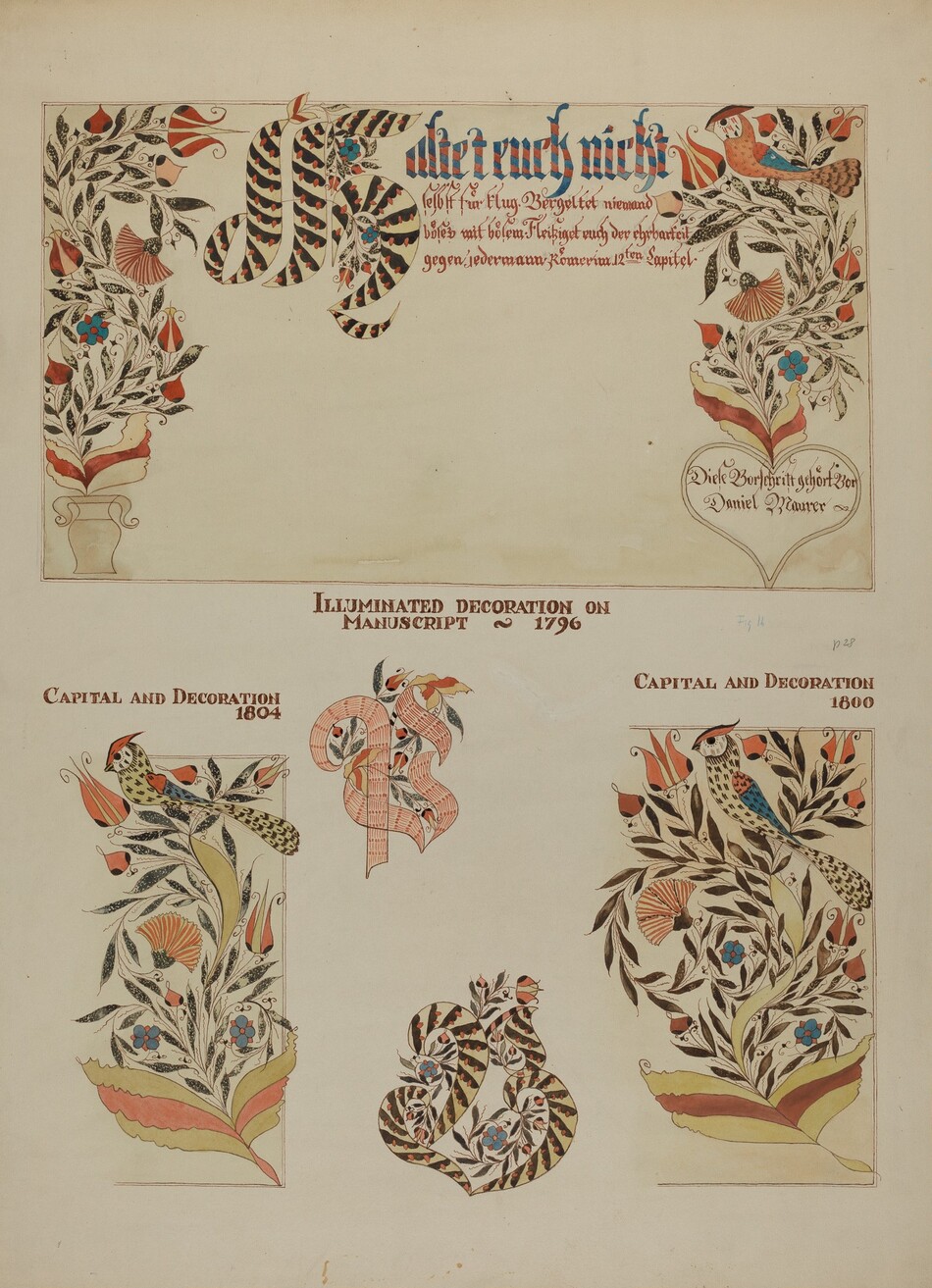

3. Pennsylvania German Crafts

One goal of the Index was to catalog the distinctive decorative styles of particular communities. For example, almost 500 renderings in the National Gallery’s collection depict Pennsylvania German objects. These include various types of furniture and cooking tools as well as toys and carved wooden figurines.

Among the most notable Pennsylvania German items are the 15 renderings of birth and baptismal certificates. They are done in a beautiful style called Fraktur design. Fraktur features vines, tulips, and other colorful decorations, often contrasted with a heavy, angular font. These designs are the kind of unique visual culture that the Index sought to preserve.

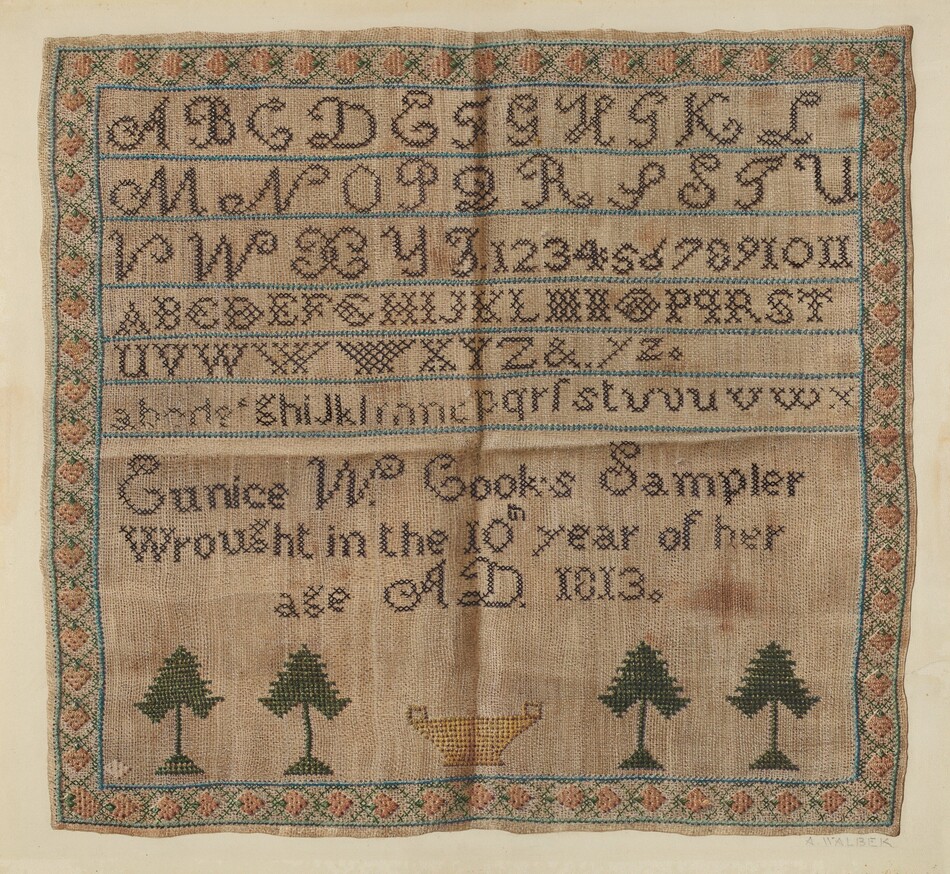

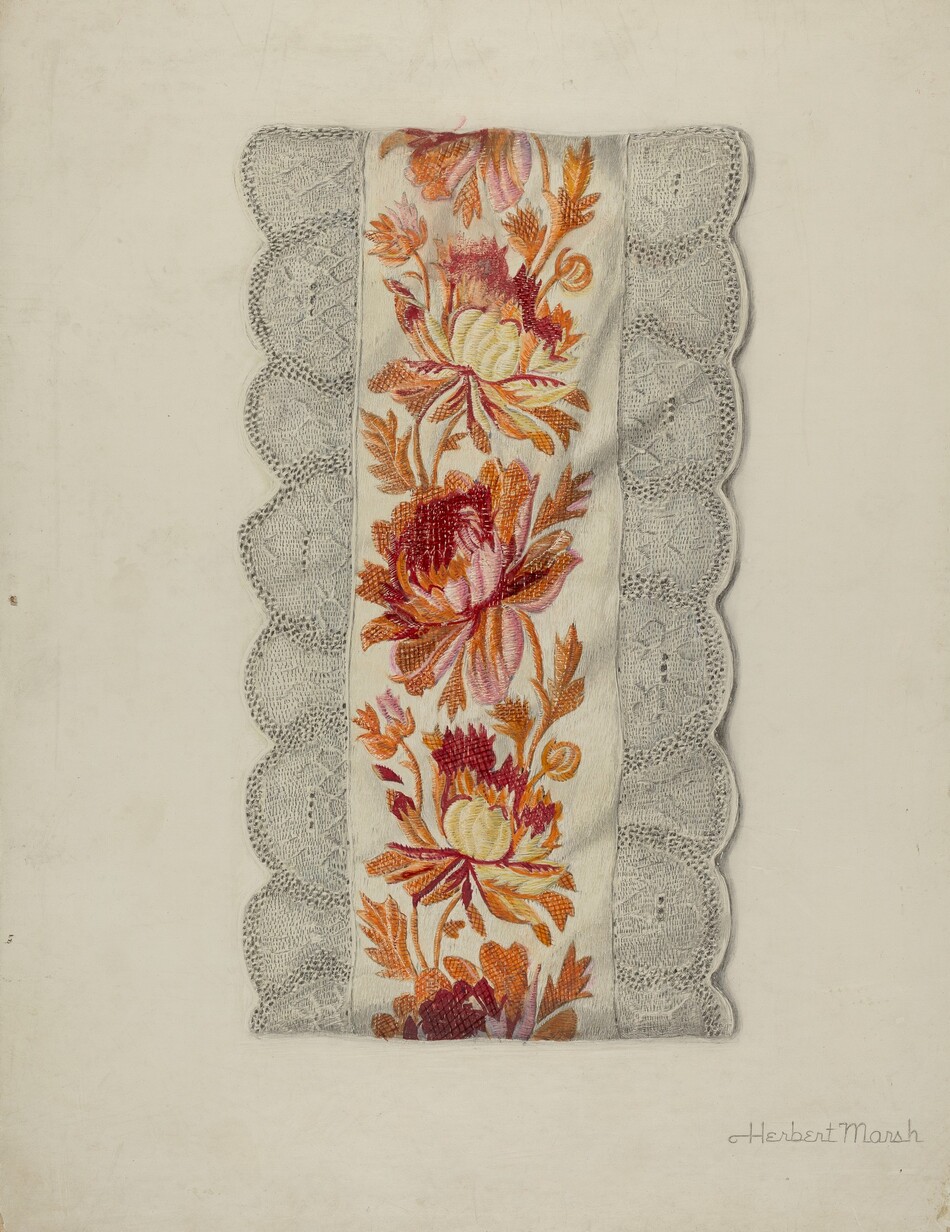

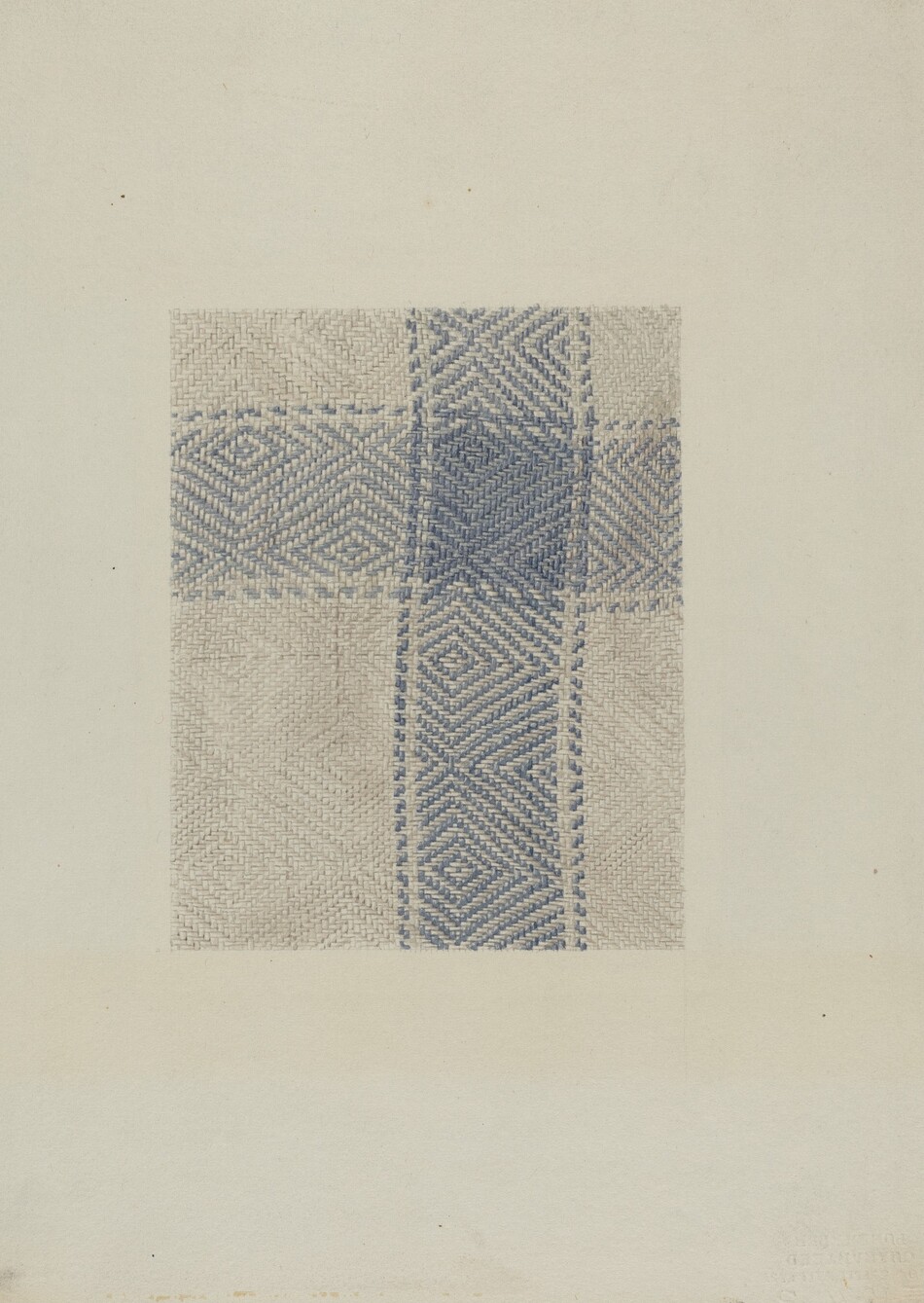

4. Intricate Textiles

Some of the most visually stunning paintings in the Index are those of textiles. Over 1,700 renderings depict textiles, including 618 paintings of quilts, 387 of embroidery, 126 of appliqués, 51 of samplers, and 36 of woven textiles. Looking at these renderings, it’s hard to believe that they were produced by an artist rather than a camera. The artists’ fine watercolor brushwork captures delicate lace, radiating tassels, and rough woven textures. While some artists on the Index project used magnifying glasses, some relied only on their eyes and an incredible knowledge of color and texture.

5. Surprising Objects

Many object types recur frequently in the Index: clothing, textiles, and furniture, for example. But there are plenty of surprises as well. In our collection, you’ll find cookie cutters (seven) and eggbeaters (four). There are a remarkable 97 renderings of butter molds! Additionally, you can find 318 renderings of dolls and 88 of marionettes and puppets. At a time when all of these objects would have been handmade, these renderings allow us to reflect on how much work would have gone into the daily tasks of feeding a family and providing joy and entertainment.

Outside of the home, there are even more surprising objects. There are also 36 paintings of carousel carvings, 39 of circus carvings, and 177 of a ships’ figureheads or stern pieces. These carved objects are some of the strangest to stumble across when looking through the index; as the rendering removes them from their context, their purpose is not initially clear. The creation of these objects, especially given the fact that they were by design extremely visible and frequently subjected to the elements, would have taken its own kind of artistry, and the renderings capture that expertly.

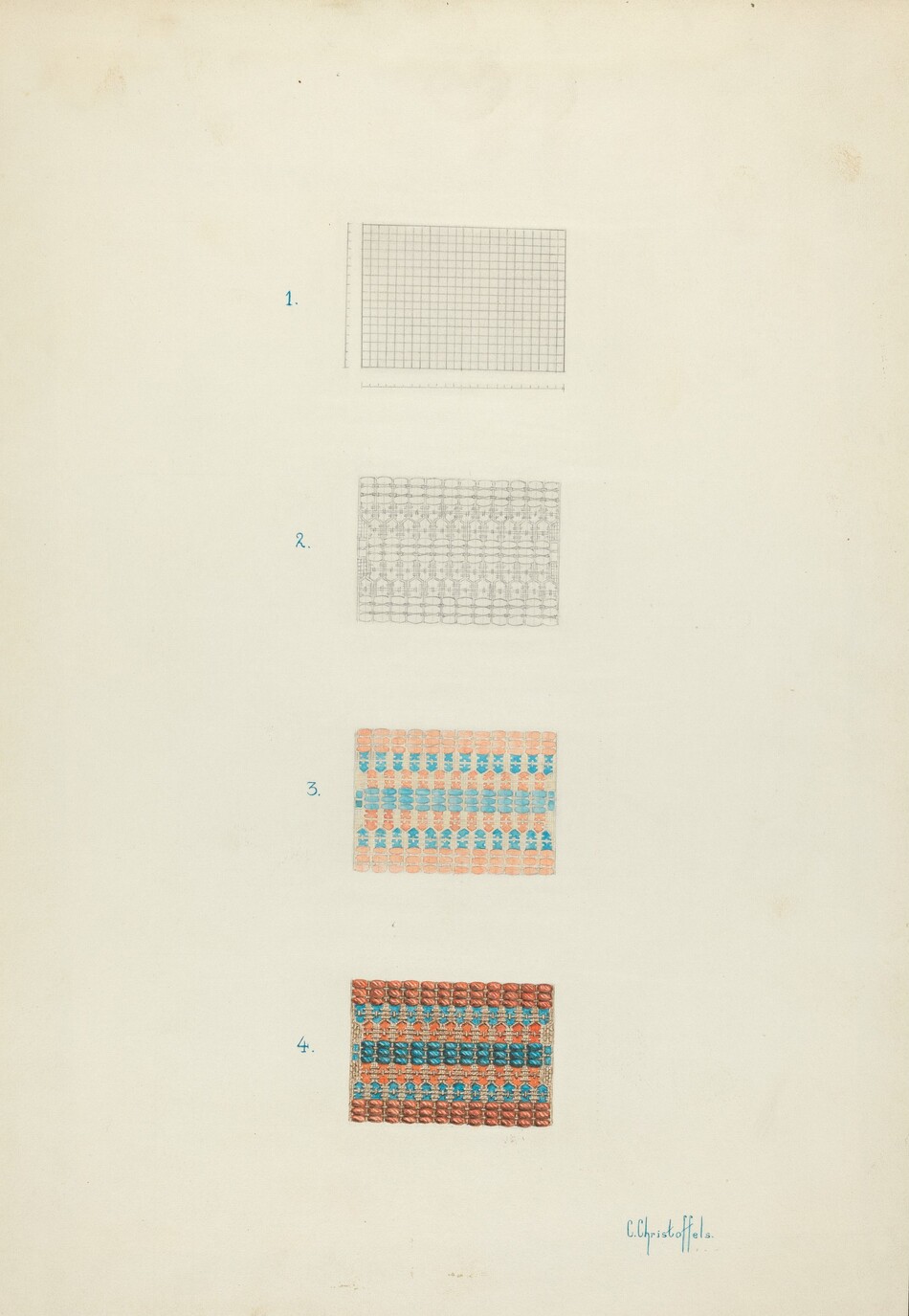

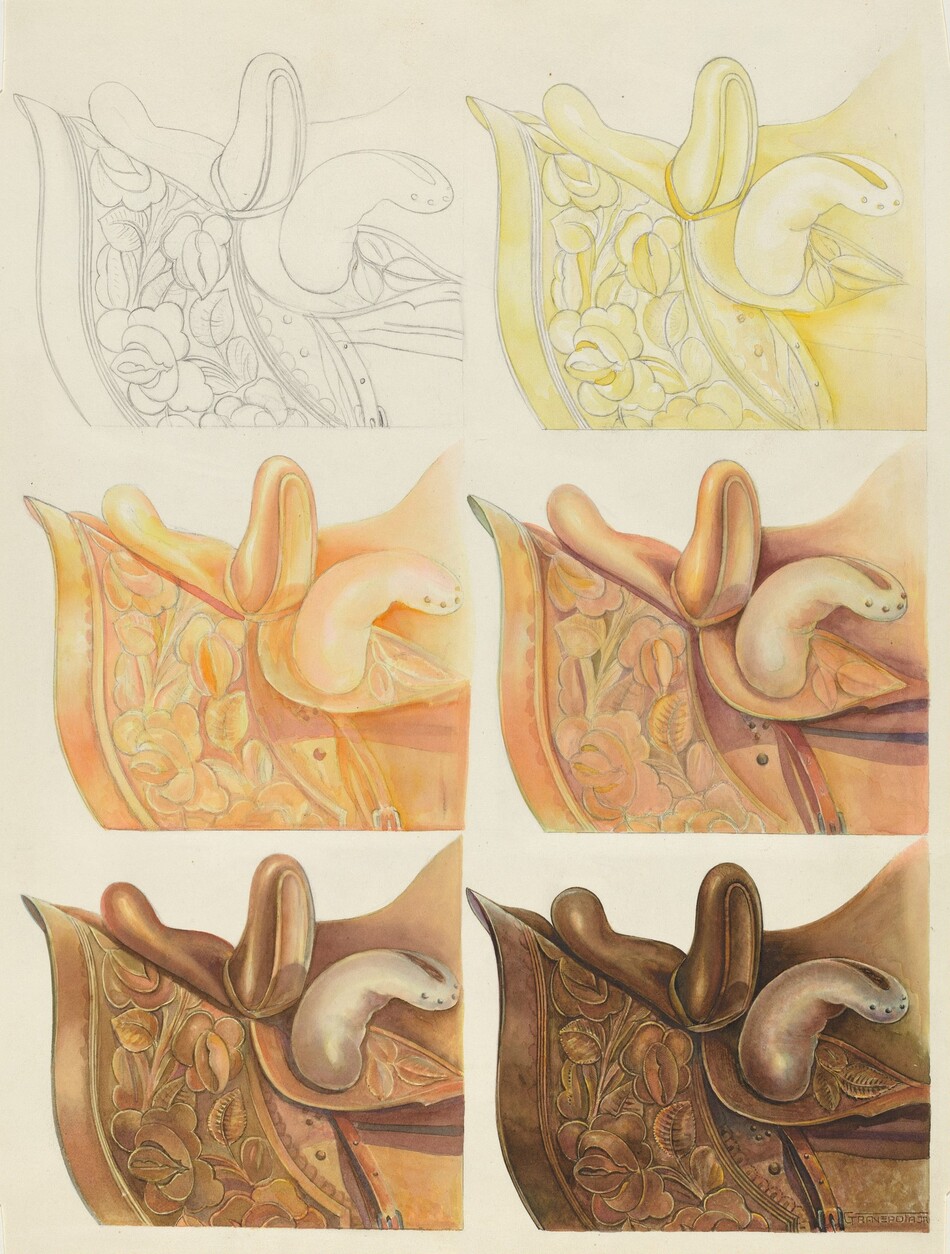

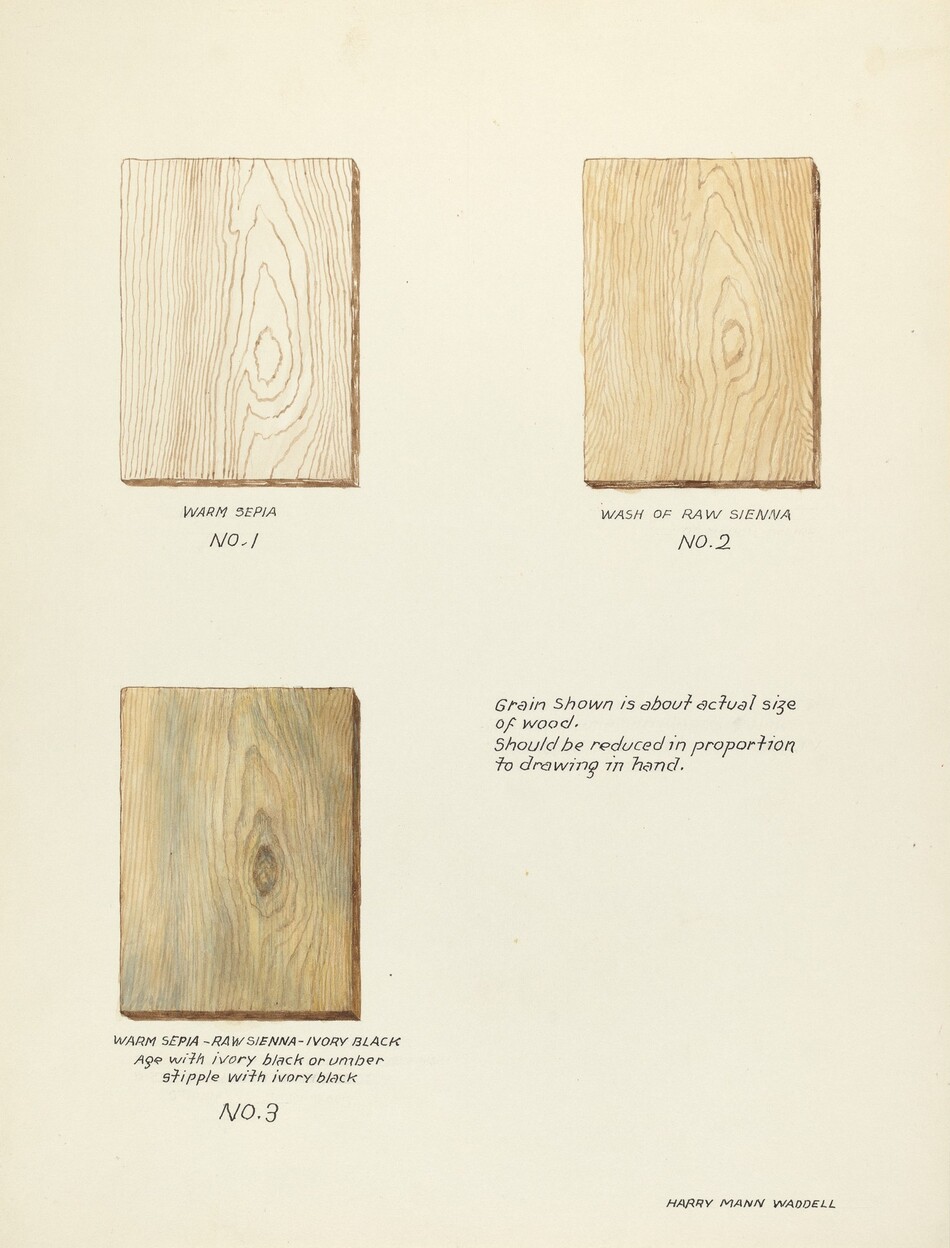

6. Demonstrations of Technique

Also included in the Index alongside finished renderings are several demonstrations of technique. These ‘instruction plates’, as the artists called them, show the process of building up pigment on the paper to realistically achieve the texture of metal, wood, or fabric. They provide us with fascinating insight into the process Index artists used and the standards they were held to.

One of the most striking aspects of the works in the Index is the incredible level of detail and depth. This was in part due to the project’s strict guidelines. The manual for the Index noted that the goal was for the artist to “render as faithfully as possible the object before him.” Artists had to use specific kinds of paper and paints and draw objects with the “ideal” layout and correct proportions. And artists such as Elizabeth Moutal and Suzanne Chapman from the Massachusetts office would travel across states, sharing their technique with other Index artists.

7. Artists Breaking the Mold

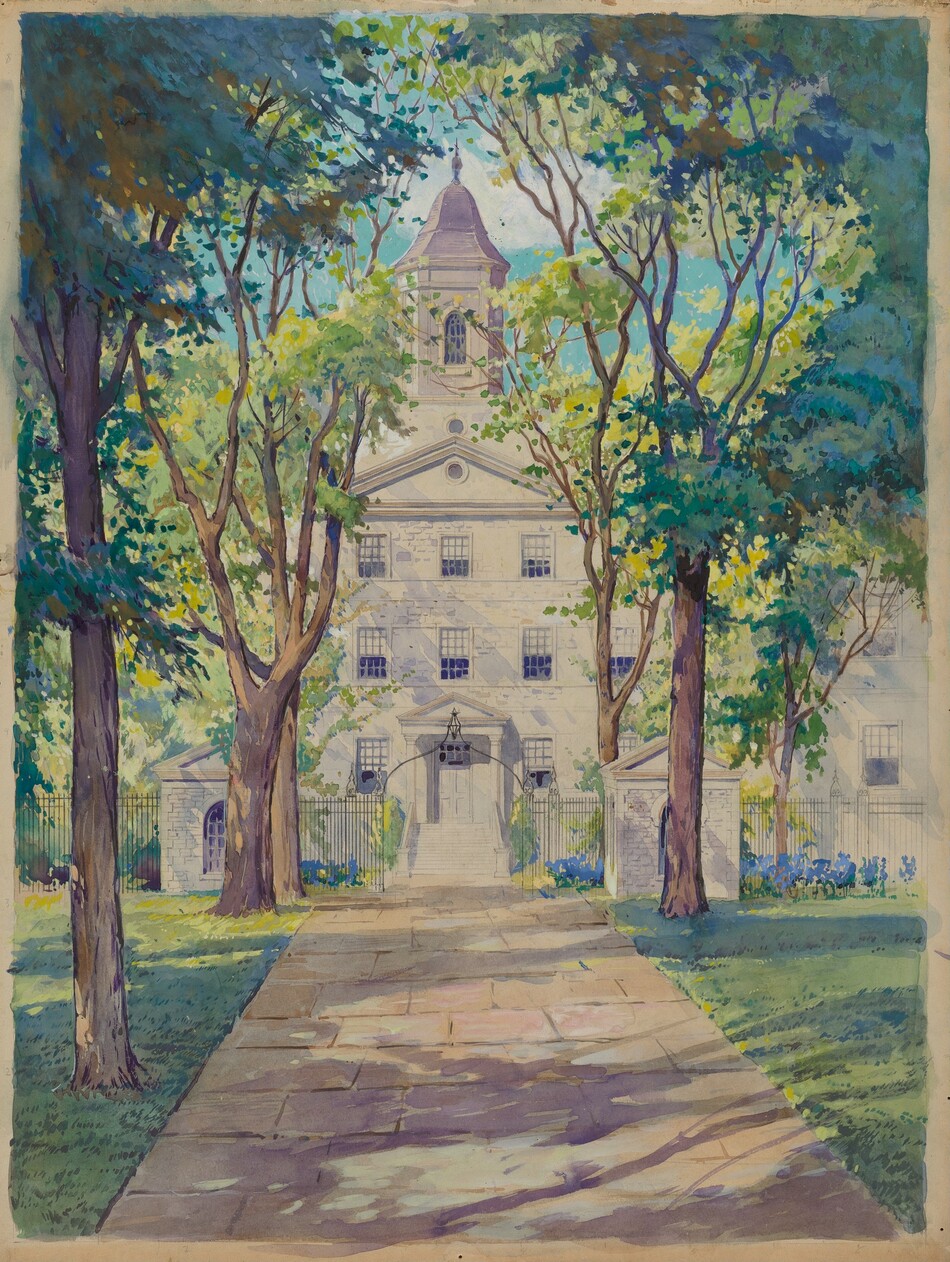

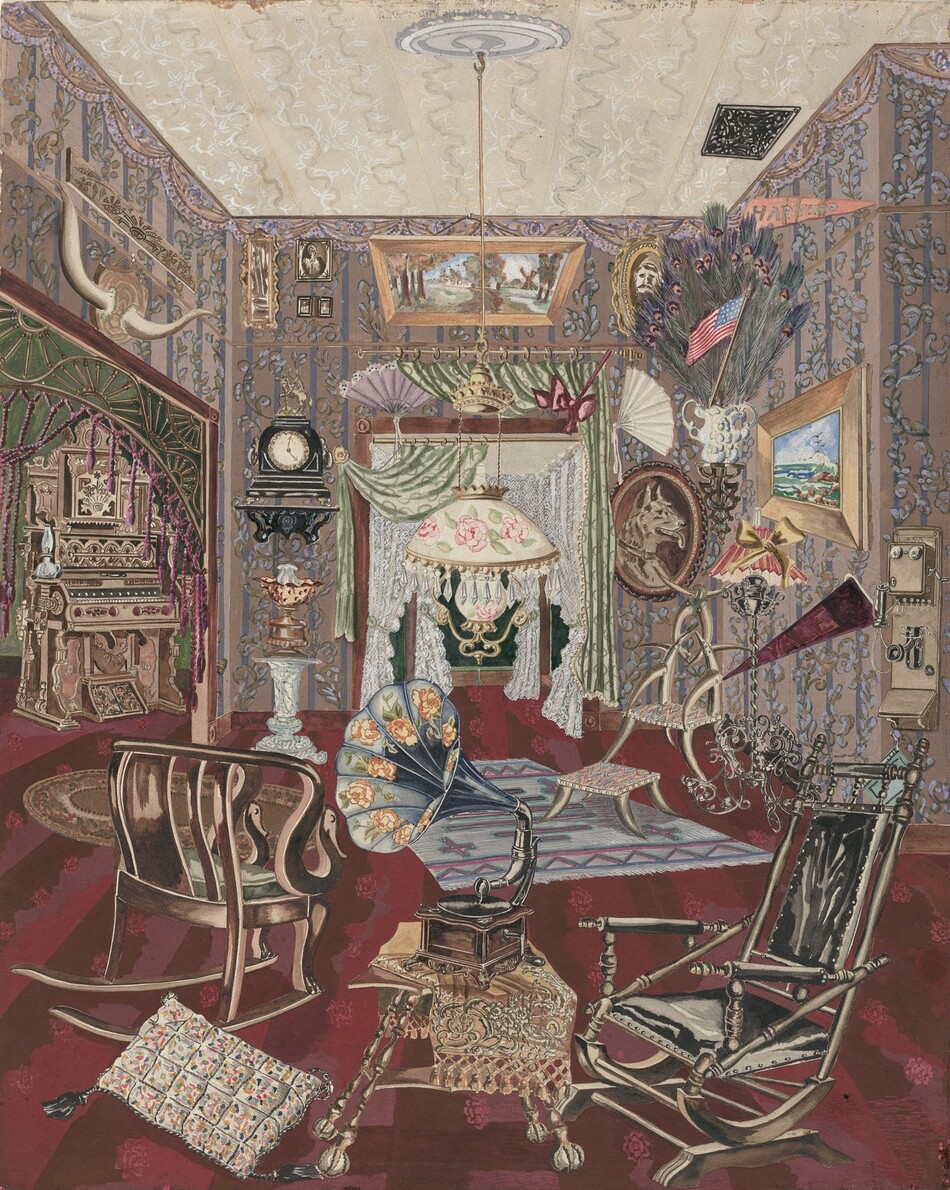

Despite the strict standards of the Index, a few artists found ways to be creative. It’s unclear why some had more freedom, but it likely varied by state office and supervisor. Gilbert Sackerman and Perkins Harnly, who both strayed from the typical aesthetic of the Index, were both involved with the New York City office.

Both artists showed their subjects in context, rather than on the blank background that was the Index standard. Sackerman painted remarkably stylized watercolors. Especially in his paintings of gardens, he often used loose brushstrokes, capturing less detail, but focusing more on color, light, and shadow. And Harnly’s paintings look so different that it’s not immediately apparent they were made for the Index. Rather than showing objects in isolation, Harnly painted cluttered rooms typical of a Victorian aesthetic. Harnly’s renderings were popular with the public—in fact, in 1946 the National Gallery hosted a traveling exhibition of 19 of Harnly’s renderings from the Index of American Design. Another Index artist, Elizabeth Benson, noted that she “thought they were really a little too much,” before acknowledging that “people loved them, and [it] was one of the more popular exhibitions.”

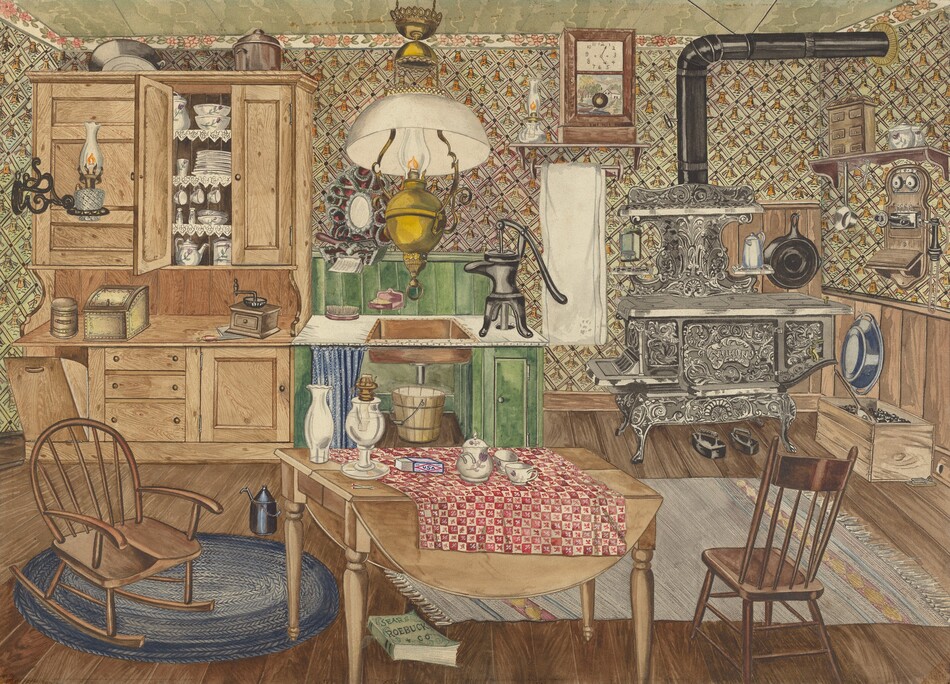

The Index offers a fascinating snapshot of American life. Its paintings reveal how Americans decorated their homes, the tools they used in their kitchens, and the everyday items that defined certain cultural practices. But the Index is not an objective record—it is a product of its time. The objects rendered were made in the 18th and 19th centuries, and they reflect the prejudices of the period. Also, selecting which items to include in the Index not only reflected American culture but also expressed a clear vision of what it was and wasn’t. Exploring the Index with a critical eye and considering its historical context gives us an even deeper understanding of the American past.

Explore the Index of American Design

The Index is made up of 18,257 watercolor works by some 1,000 artists. A Federal Art Project dating to the Great Depression, it sought to identify and preserve a national, ancestral aesthetic for the United States. The watercolors depict American folk and decorative arts objects from the colonial period through 1900.

You may also like

Article: Creating an Index of American Design

The US government once employed artists to draw pictures of designs from historical objects. The idea is reimagined by artists today.

Article: Dressing for Dinner in the Gilded Age

This 19th-century dinner dress captured in the Index of American Design gives us a glimpse of how the wealthy dressed for dinner.