Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

Explore the artistic influences in the installation Back and Forth.

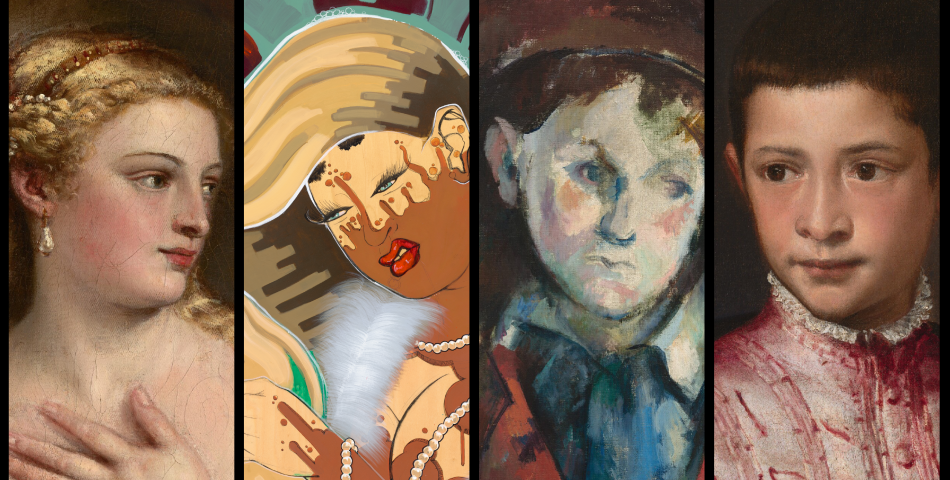

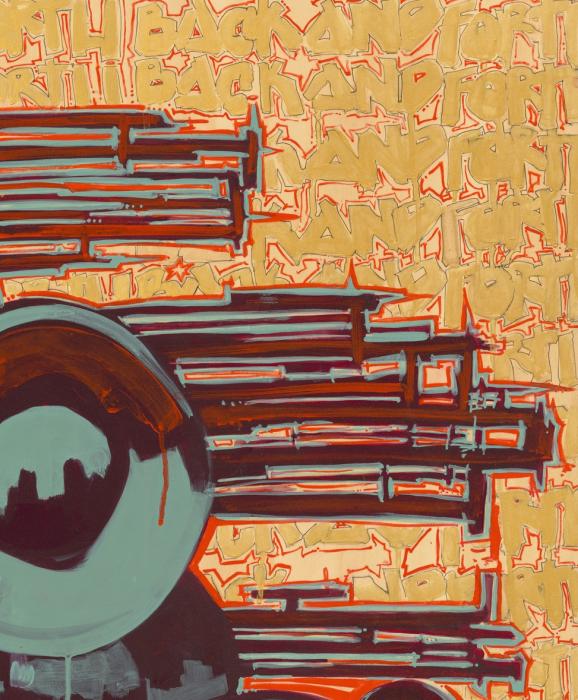

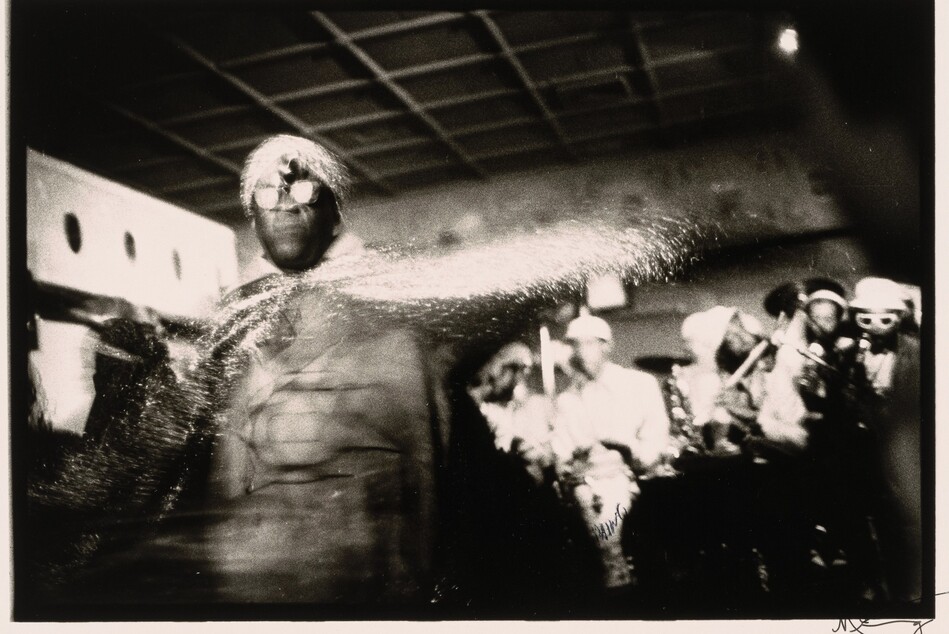

Like a record spinning on a turntable, the progression of painting is not linear—scratch the record, and the sound moves back and forth in time. Artists find inspiration across centuries, and their works exist in conversation with those both before and after them. Our understanding of art unfolds through this mix and remix.

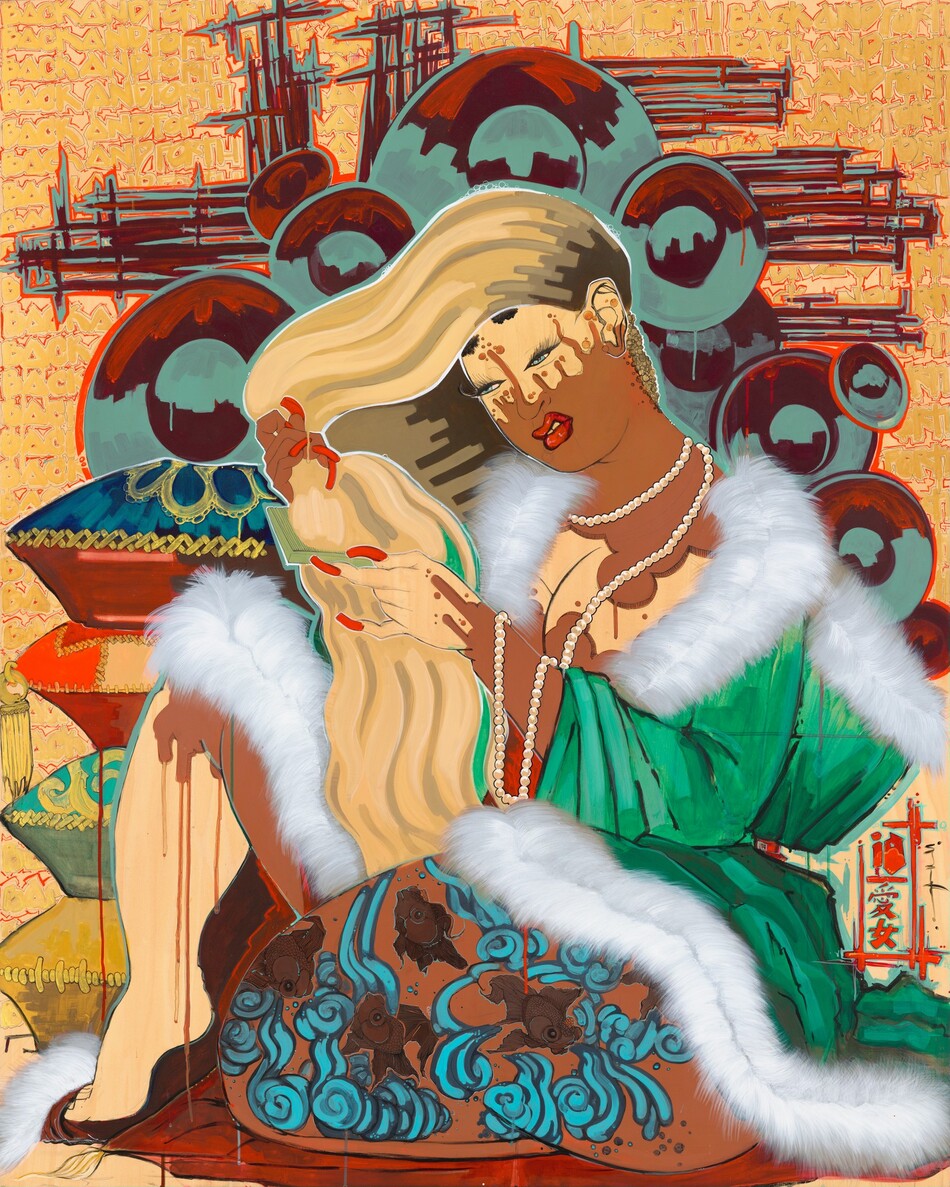

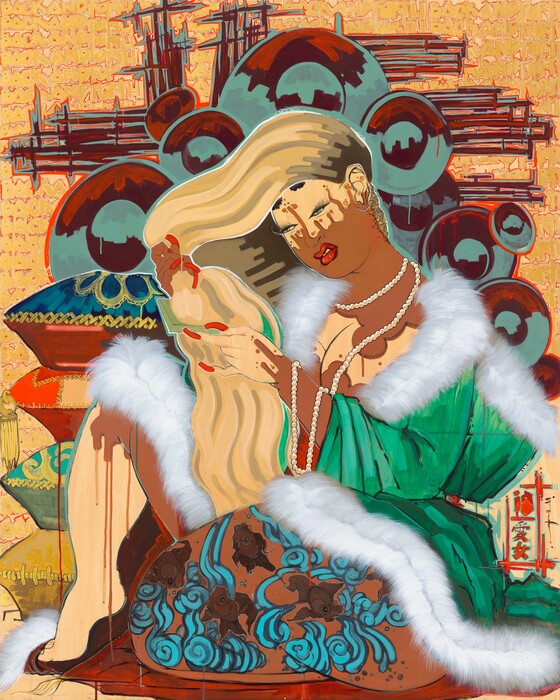

That's what visitors are invited to explore in the installation Back and Forth. In addition to considering artistic influences, we examine how contemporary paintings can “remix” the works of artists who preceded them. How does Rozeal.’s afro.died.T echo with paintings by Paul Cezanne and Titian? And how does it illuminate new aspects of those works, painted hundreds of years earlier?

Gaze

Neither Titian’s Venus with a Mirror nor Rozeal.’s afro.died.T. meets our gaze. We are free to stare at them without confrontation. That’s how both artists depict the Greco-Roman goddess of love and beauty. Venus was her Roman name, and “afro.died.T” is a play on the Greek counterpart, Aphrodite.

Both Titian and Rozeal. paint this goddess with a full, rosy pouts. afro.died.T’s lips curl in a sneer, while Venus smiles.

Both goddesses drip with pearls. The lustrous gems illuminate their complexion.

And they both wear luxurious velvet trimmed with furs. Titian adds glinting silver and gold embroidery to Venus’s deep red cloak.

The goddesses behold their own appearances. Venus admires herself in the mirror, while afro.died.T lifts her long hair.

Titian constructs Venus’s classical beauty using sumptuous surfaces and texture, shine and sparkle, and soft, pillowy flesh. But Rozeal.’s subject seems to have a far more ambivalent relationship to beauty standards.

Rozeal. painted this Aphrodite based on women depicted in traditional Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

Kitagawa Utamaro, Two Women, ca. 1790, woodblock print; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Howard Mansfield Collection, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1936.

The artist began painting figures in this style after discovering ganguro, a subculture that emerged among Japanese women in the 1990’s. Obsessed with American hip hop music, they wore blackface (ganguro literally means “black face”) as well as signifiers of African American culture. “Being African American, I’m flattered that our music and style is so influential. But I have to say that I find the ganguro obsession with blackness pretty weird and a little offensive,” Rozeal. said. “My paintings come out of trying to make sense of this appropriation.” Her mixed-complexion goddess reflects those concerns.

Space

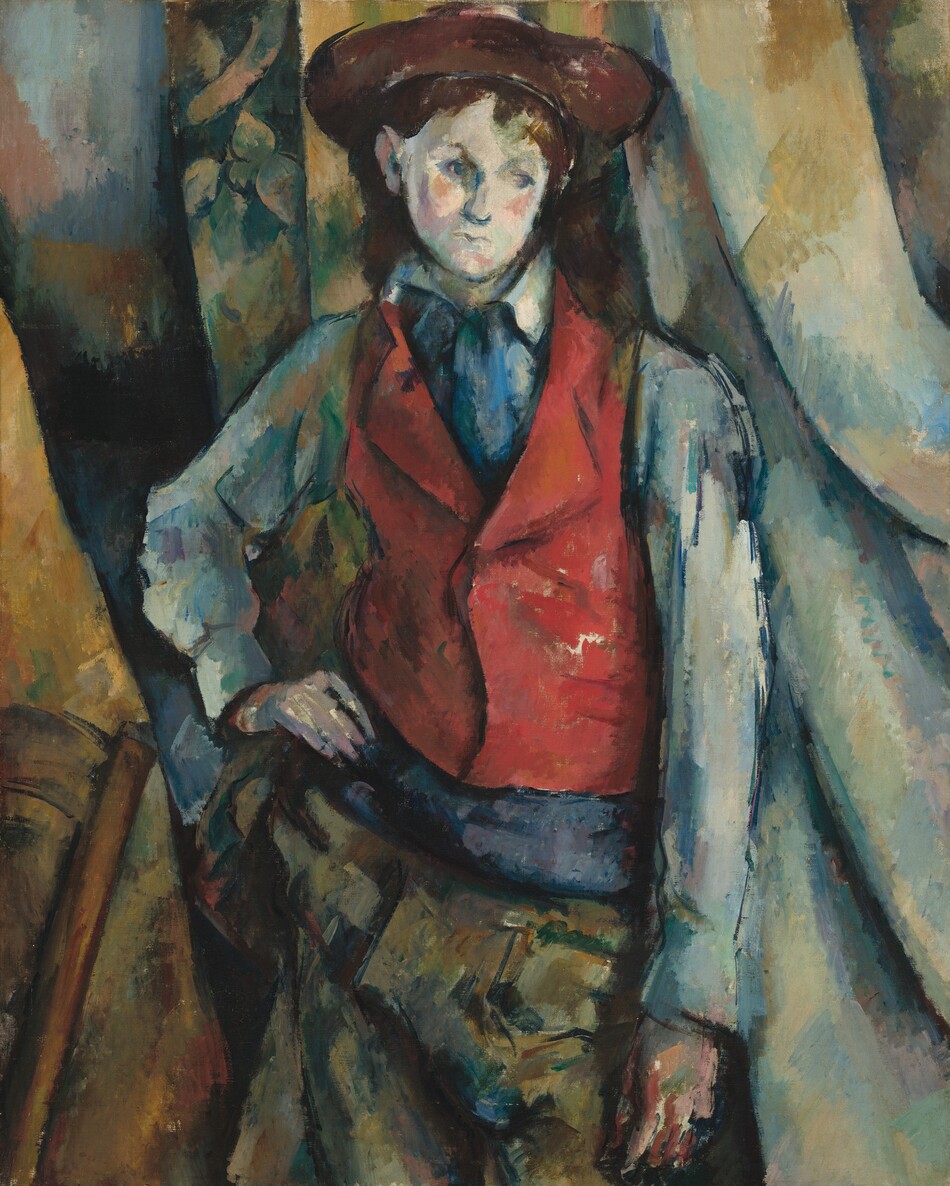

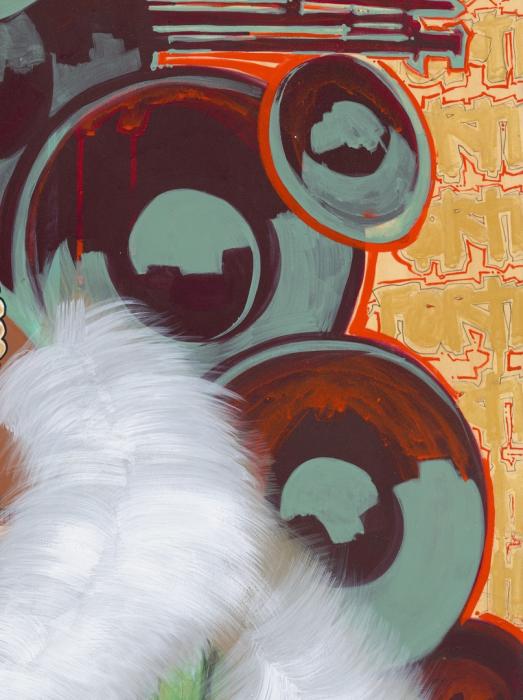

Step into the worlds that Rozeal.’s afro.died.T and Paul Cezanne’s Boy in a Red Waistcoat inhabit. Visual clues suggest interior spaces. A cushion on the floor supports afro.died.T, and there is a stack of pillows behind her. The back of a chair peeks into the frame of Cezanne’s painting. The vertical lines behind the boy could be curtain folds.

But there’s much that’s disorienting too. Colors and patterns spill over from background to foreground. Behind afro.died.T are subwoofers, abstract crosshatches, and a repeating lyric: “back and forth” from Willow Smith’s catchy “Whip My Hair.” Meanwhile, unblended blocks of blues and grays form the backdrop of Cezanne’s painting.

Pops of red delineate both figures from these background. Rozeal. uses a bright red to outline the subwoofers. And the boy’s titular red waistcoat carves out his blue-gray shirt from a matching background.

Through a combination of abstraction and realistic details, these painters construct worlds within their picture frames.

Pose

Cezanne’s Boy in a Red Waistcoat and Titian’s Ranuccio Farnese strike similar poses. Both are in contrapposto, an Italian term for standing with one’s weight shifted over one leg. Tilting shoulders and hips in opposite directions, this pose gives the body an elegant line. It also affects an attitude of nonchalance and ease.

Both figures’ right hands (on our left) rest at their hips. The pose creates tension, bringing adult swagger to the youthful figures.

Neither boy looks at us directly, which adds an air of shyness to their otherwise confident stances. In Cezanne’s painting, the boy’s features remain vague, emerging from blotches of lavender, aqua, and pink.

In contrast, Titian captures every detail of Ranuccio Farnese’s face—and his anxious, wistful expression.

Ranuccio was born to the powerful, aristocratic Farnese family. When he was only 11, his grandfather Pope Paul III sent Ranuccio to Venice. There, he was to assume an important position with a religious order, the Knights of Malta.

Subject

Consider also the subjects themselves. In Ranuccio Farnese, Titian creates psychological depth. He strips away all background, directing our focus to Ranuccio, a boy on the cusp of great responsibility. We sense his conflicted emotions: uncertainty and pride.

Venus with a Mirror, on the other hand, is not a portrait. The woman in this painting isn’t a particular person; as the Roman goddess Venus, she represents ideal beauty. So Titian devotes his attention to surfaces: the goddess’s fur-lined velvet cloak, her glistening pearls, her silky blond hair, and her soft skin. The sumptuous background is also devoted to lush and glittering surfaces—velvet drapes, a silk divan. Consider how Titian handles the difference between portrait and allegory.

In these four works, Rozeal., Titian, and Cezanne speak to each other across space and time. What other points of connection, or departure, can you see? The closer you look, the more will emerge.

You may also like

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Interactive Article: How the Index of American Design Kickstarted Edward Loper’s Art Career

The acclaimed Delaware artist first brought his artistic ambitions to life drawing decorative art objects for the Work Progress Administration project.