What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Poet Larry Neal, who coined the term Black Arts Movement, described it as “a cultural revolution in art and ideas.” This movement included poets, playwrights, musicians, filmmakers, photographers, and painters. They came together to make art that advanced civil rights and celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

This cultural revolution shook up the art world in the 1950s and ’60s. It embodied the struggle for self-determination championed by global freedom movements. New collectives, workshops, and collaborations emerged. Creatives made art that promoted Black dignity, hope, and freedom. They asked, how could art inspire social and political change? And what would it look like?

Photography was a driving force from the beginning, playing a critical role as both a communications tool and art form. Learn more about the movement and photography’s part in it—major themes in our exhibition Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985.

1. Its origins are in the civil rights movement.

Harry Adams, Protest Car, 1962, inkjet print, Courtesy of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge. © Harry Adams. All rights reserved and protected.

Our exhibition begins in 1955, more than a decade before Larry Neal named the Black Arts Movement. That year, several events—and photographs of those events—helped catalyze the civil rights movement.

In September, Jet magazine was one of several publications that printed open-casket photographs of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was lynched in Mississippi. Those disturbing images were seen across the country, including by a woman in Montgomery, Alabama: Rosa Parks. That December, Parks sat in the front, “white only” section of a segregated bus. The driver demanded that she give up her seat to a white passenger. She refused. As she later recounted, Emmett Till was on her mind in that moment.

Parks, in turn, was photographed sitting at the front of the segregated bus. Those images, and others like them, brought widespread awareness to the struggles for equal rights. Organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) encouraged photography of their marches, demonstrations, and acts of nonviolent civil disobedience. SNCC even taught some members to use a camera. Lifelong activist Maria Varela became a SNCC photographer after recognizing the need for more images of Black life to support the movement.

2. Poets, writers, and playwrights led the movement.

The beginning of the Black Arts Movement is often pinned to poet, playwright, and writer Amiri Baraka founding the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in 1965. Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Audre Lorde were among the many writers and poets active in the movement. Some collaborated with visual artists, even forming collectives such as the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) in Chicago.

OBAC writers, scholars, painters, and photographers collaborated to create the Wall of Respect community mural in 1967. It commemorated key figures in African American history, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Muhammad Ali, and Nina Simone. The mural was like a two-story collage that covered the facade of a building in the city’s South Side neighborhood. It incorporated paintings by several artists alongside mounted photographs by Roy Lewis and Darryl Cowherd. At the center was Amiri Baraka’s poem “SOS,” which opens, “Calling all black people.” The mural was demolished in 1972, but photographs by Roy Lewis and Robert Sengstacke continue to spread its message.

3. It was inspired by jazz.

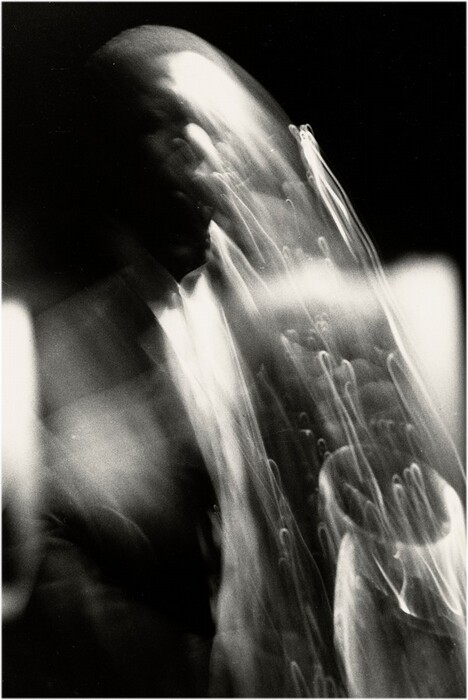

Music was an equally important part of the Black Arts Movement. Musicians John Coltrane and Sun Ra both performed at a fundraiser for Amiri Baraka’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. Their experimental and expressive jazz inspired Black Arts Movement writers and artists.

In Coltrane at the Gate, photographer Adger Cowans depicted the saxophonist’s energy. Ming Smith captured the magic of a Sun Ra performance. For his homage to saxophonist Charlie Parker (who was commonly known as “Bird”), painter Raymond Saunders embraced the spontaneous spirit of jazz. Saunders collaged a newsprint photograph below the word “bird” written in a chalklike white script.

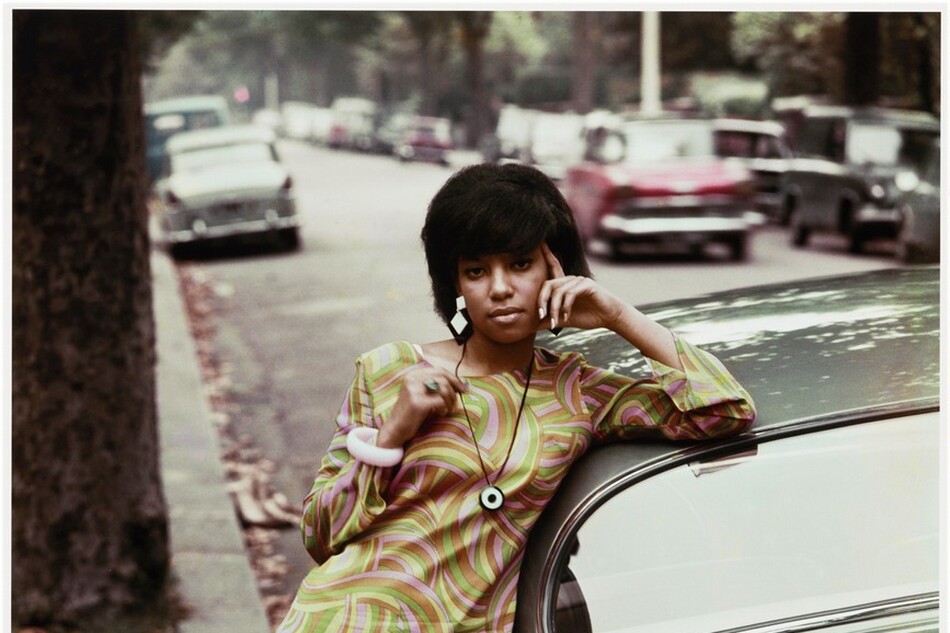

4. It celebrated Black beauty.

The Black Arts Movement celebrated the “beauty and goodness of being Black,” as Larry Neal put it. Photographer Kwame Brathwaite helped popularize the phrase “Black is beautiful.” Brathwaite was a pioneer of uplifting Black identity. He helped found groups that challenged conventional standards of beauty and celebrated African heritage. They organized fashion shows, created “Black is beautiful” products, and operated a photography studio.

In Untitled (Portrait, Reels as Necklace), Brathwaite adorned the model with a necklace made from film developing reels to “expose” her beauty. More than a decade later, Carla Williams created a self-portrait that echoed Brathwaite’s work. Showing herself in curlers, Williams challenged popular notions of beauty.

5. It brought artists together.

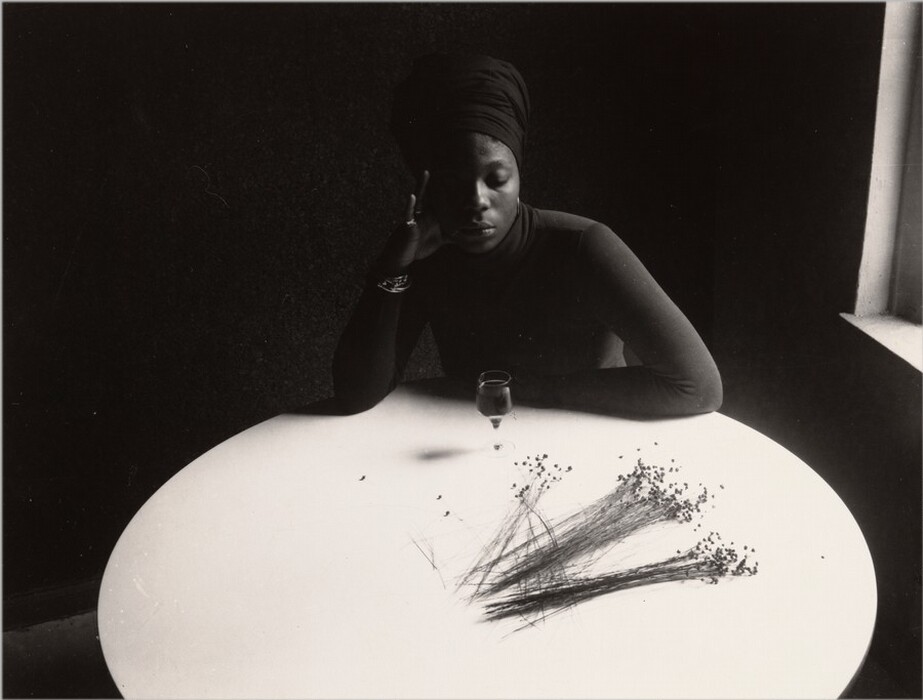

Small collectives of visual artists and photographers came together around the principles of the Black Arts Movement. In New York, the Kamoinge Workshop photography collective met regularly to critique each other’s work, debate photography’s purpose and aesthetics, and share tips. They created a space for their art by developing their own portfolios and exhibitions. The workshop also produced the groundbreaking Black Photographers Annual between 1973 and 1980.

A group of Chicago artists formed AfriCOBRA. The collective’s founders defined their own aesthetic principles, aimed at creating “images that jar the senses and cause movement” and “images designed for mass production.”

6. It spread across the Atlantic.

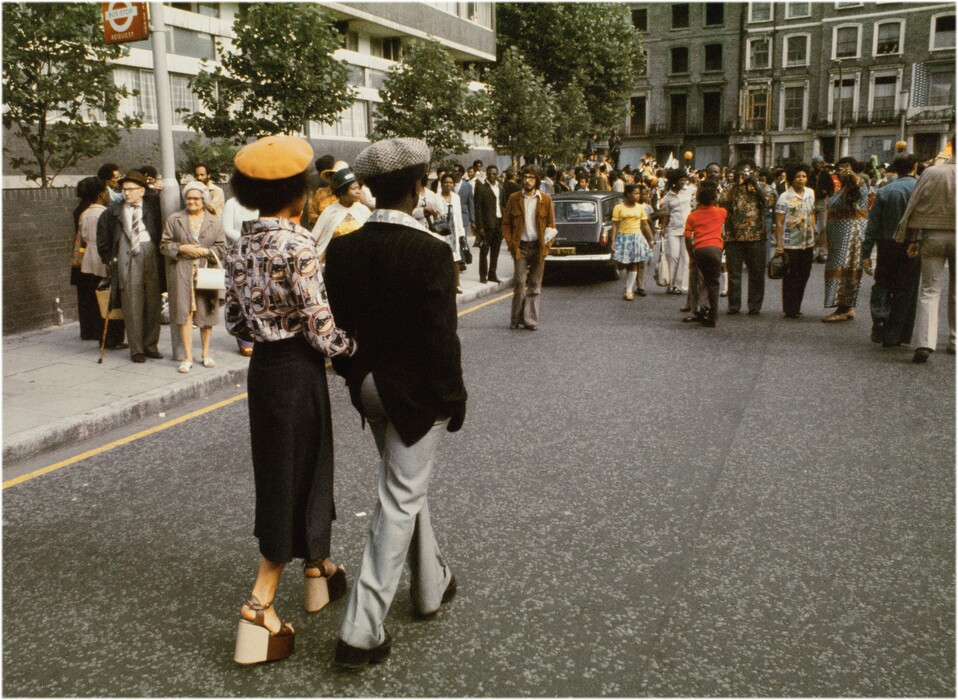

The Black Arts Movement made an impact beyond the United States. In Great Britain, Raphael Albert organized and photographed Black beauty pageants in London. James Barnor focused on style, migration, and Black city life in London and in Accra, Ghana. Horace Ové photographed the British Black Power Movement. He also captured scenes of the West African and West Indian communities in London, like his Walking Proud, Notting Hill Carnival.

Samuel Fosso opened his first photography studio in Bangui, Central African Republic, at age 13. After finishing with clients, Fosso would use his studio to experiment with self-portraits. He wore an array of costumes and adopted personas, often taking inspiration from the pictures of Black Americans he saw in magazines shared by American Peace Corps volunteers.

7. It influenced generations of artists.

By the end of the 1970s, the literary arm of the Black Arts Movement had waned, but a new generation of artists and photographers carried on its spirit. Coming out of art school, photographers such as Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson explored more personal, metaphorical, and conceptual ideas.

In her Family Pictures and Stories series, Weems made her own family the subjects. The intimate photographs presented a counterargument to claims that many Black Americans faced poverty and struggle as a result of weak family structures. Weems paired the photographs with brief stories about each family member.

Exhibition : Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985

The first exhibition to consider photography’s impact on a cultural and aesthetic movement that celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

You may also like

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.

Article: From Old Car Tires, Chakaia Booker Reveals Beauty and Devastation

Transforming discarded tires into monumental sculptures, the artist reflects on the environmental impact of our daily commutes.