The Marvelous Details of Joris Hoefnagel’s Animal and Insect Studies

Scroll to discover tiny brushstrokes, hidden meanings, and the immense impact on our understanding of the natural world.

In the late 1500s, Netherlandish artists became interested in the natural world like never before. Local insects and other previously overlooked beestjes—“little beasts” in Dutch—captured their imaginations. And new species arrived at their doorsteps via colonial expeditions and global trade.

Artists like Joris Hoefnagel studied insects, birds, and other animals as part of a larger community of naturalists. Hoefnagel captured his observations in The Four Elements, a series of about 300 watercolors bound into four books.

Each volume is named for a classical element. Aqua (Water) features images of aquatic animals, Terra (Earth) of animals that walk on the earth. Aier (Air) combines images of birds with plants. Ignis (Fire) holds Hoefnagel’s paintings of insects—though we don’t know why. One possible explanation is that both insects and fire are constantly changing form.

Hoefnagel paired many drawings with Latin inscriptions of Bible verses, bits of poetry, mottos, or proverbs. These texts encourage viewers to find symbolic meaning behind the images.

Keep scrolling to marvel at the details and hidden lessons in three of Hoefnagel’s remarkable watercolors. See these and other works in Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World. On view through November 2, the exhibition presents art depicting animals alongside specimens and taxidermy from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

The Hedgehog “Trick”

An inscription at the bottom of this image compares hedgehogs with foxes.

The Shadow of the Stag Beetle

Like most of the insects in Hoefnagel’s watercolors, the stag beetle was likely a creature he observed in real life. They’re native to Europe.

His image of the beetle resembles one by another artist: Albrecht Dürer. The German artist had painted a stag beetle decades earlier in 1505.

Albrecht Dürer, Stag Beetle, 1505, watercolor and gouache; upper left corner of paper added, with tip of left antenna painted in by a later hand, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 83.GC.214

At first glance, the beetles look almost identical. But take a closer look.

Hoefnagel’s study allows us to take our time observing a creature with a brief lifespan—male stag beetles live for only a few weeks. Other artists, like printmaker Claes Jansz Visscher, copied this image of the beetle, sharing it with more naturalists and collectors.

Jacob Hoefnagel, published by Claes Jansz Visscher, Diversae insectarum volatilium icones ad vivum accuratissimè depictae (Images of a variety of flying insects, very accurately drawn from life), 1630, bound volume, National Gallery of Art Library, J. Paul Getty Fund in honor of Franklin Murphy

The Dragonfly’s Wings

Hoefnagel’s insects are so realistic that it feels as if they could crawl or fly off the page. His study of dragonflies on plate 54 of Ignis is all the more lifelike because it includes their actual wings.

Working in a time before photography, Hoefnagel froze the ever-fluttering dragonflies, allowing us to admire the minute details of their patterned body and translucent wings.

Aeshna cyanea (Southern Hawker Dragonfly), loan courtesy of National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, USNMENT00161896. Image: Nearby / Alamy Stock Photo

The Impact of Hoefnagel’s Studies

The Four Elements was a personal project, which Hoefnagel started in the 1570s. He carried it with him through years of travel and work as a court artist, including for the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II.

These watercolors served as sources for a series of 52 prints engraved by Hoefnagel’s teenage son, Jacob. That series, Archetypes and Studies, offered the earliest printed images of dozens of species.

The relatively cheap prints enabled little beasts to multiply and crawl out into the world. They inspired a broader interest and study of nature which continues today.

Exhibition : Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World

Experience the wonder of nature through the eyes of artists. Look closely at art depicting insects and other animals alongside real specimens.

You may also like

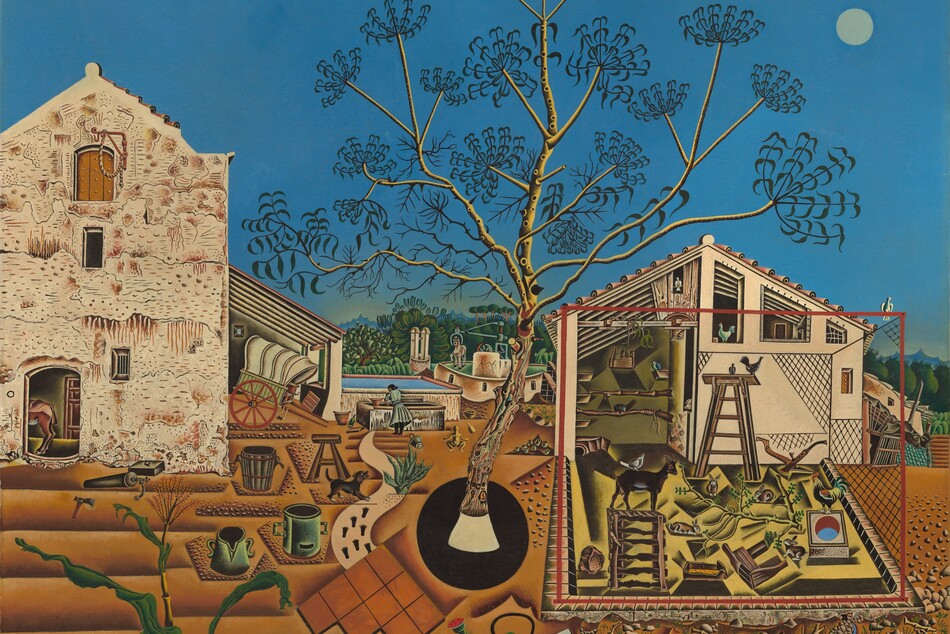

Interactive Article: Art Comes to Life in Joan Miró’s "The Farm"

Joan Miró’s complex and captivating painting is full of life and mystery.

Article: Smithsonian Scientists on How Artists Depicted Five Curious Creatures

Staff at the National Museum of Natural History helped us identify the animals and insects in our collection.