In Plain Sight: What to Do When You Don’t “Get” Modern Art

Modern art. Is there anything else that can strike so much fear in the heart of the average museumgoer?

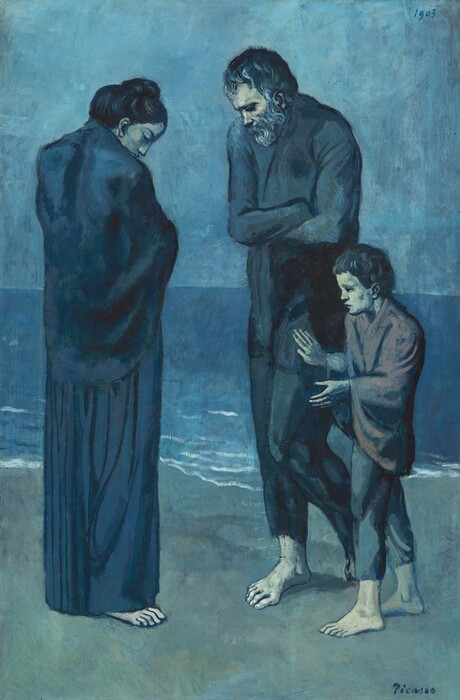

Canvases are spattered with paint, lined with grids, or barely contain shapes that seem to want to float away. Faces or buildings or trees emerge from a geometric background, but on close inspection, they break apart into brushstrokes. A car tire is cut apart and reassembled. A giant mobile floats in the air, catching the breeze. The whole world is shaded blue. Is it any wonder that, compared to the straightforward, legible works of, say, the Renaissance, this could feel destabilizing?

When it comes to modern art, it’s natural to ask, well, what does it mean? What is this work about? How did we just go from fauvism to cubism to futurism? How could I ever understand this stuff without a graduate degree?

But you can! I promise you, you can. Because modern art is all about being of its own moment—which means that we can feel free to relate it to our moment. “We’re dealing with some of the same issues about how we put the world together,” says Harry Cooper, Bunny Mellon Curator of Modern Art at the National Gallery. “I could sit down with Cezanne and have a conversation that wouldn’t feel so alien.”

And it’s true. We can recognize from Cezanne’s work just how relatable and human he was, how similar to us. This is what modern art is all about: human beings painting the modern world, life as it is being lived. Not life separated from us by allegory, mythology, or biblical narrative, but the real, gritty, actual world. And if an artist is so present in their world, we can connect with it as well. “I definitely feel drawn to [works] that evoke some emotion in me,” said Jade Rosser, a visitor. “You can feel the temperature in the colors, the different emotions the artist felt. It makes me feel that way too.”

This episode, the last of our series, explores art that may not always make sense to our eyes but can still speak to our souls. Because so much of modern art is abstract. Or at the very least, it’s nonrepresentational: it doesn’t necessarily depict a concrete thing.

Modern art invites our interpretations. It actually thrives on them. We are all full of abstract feelings, so we can relate to these paintings more than we might think. Sometimes it can feel like seeing objects in clouds. Sometimes it can feel like a Rorschach test. Sometimes you can see something that you know the artist didn’t intend, but whatever. It’s okay. You looked closely, and you saw what you saw.

So find the images in the clouds. Bring your own experiences and figure out what a work reminds you of. It’s so much easier, after that, after the spark is lit, to absorb art historical information. To understand the artist’s context and intentions. To sit down with Cezanne and smell the fresh, drying paint, and realize how much we share.

Episode Highlights

“It's a very cold painting. You can kind of feel the temperature of it. I like piece’s that make me feel that way. The great sadness in this just speaks very loudly to me.”

– Jade Rosser, Visitor

“The artist was inspired by his time in Texas and seeing after a tornado the tangles of wire. This one little girl last summer who heard her talking with her mother, and she said, this looks like a bowl of spaghetti. I just love that. We light the spark, we don't fill the bucket.”

– Brett McNish, Grounds Manager

“The last time I was here, one of the guards came to me and said, ‘I've worked here for two years, and I don't understand why what anybody sees when they look at Rothkos.’ And I said, ‘Do you go to church?’ And he said yeah. I said, ‘Well, how do you feel when you're singing in the choir and all the music blends together and you just go someplace? That's how I feel when I see them.’ He nodded, because he knew that feeling of giving yourself over to something.”

– Claire Rosser, Visitor

Storytellers in Residence

Storytellers can help us understand art in new ways. We invited two to spend a week at the museum and explore art that inspired them.

You may also like

Article: In Plain Sight: Finding Your First (Art) Love

How can we learn to fall in love with a work of art? From curators who share the works that sparked their lifelong passion for art.

Article: Exquisite Corpse with Kerry James Marshall (and friends!)

The history painter takes inspiration from an old surrealist game — and so can we, as an opportunity for connection.