Seven Things to Know About Australian Indigenous Art

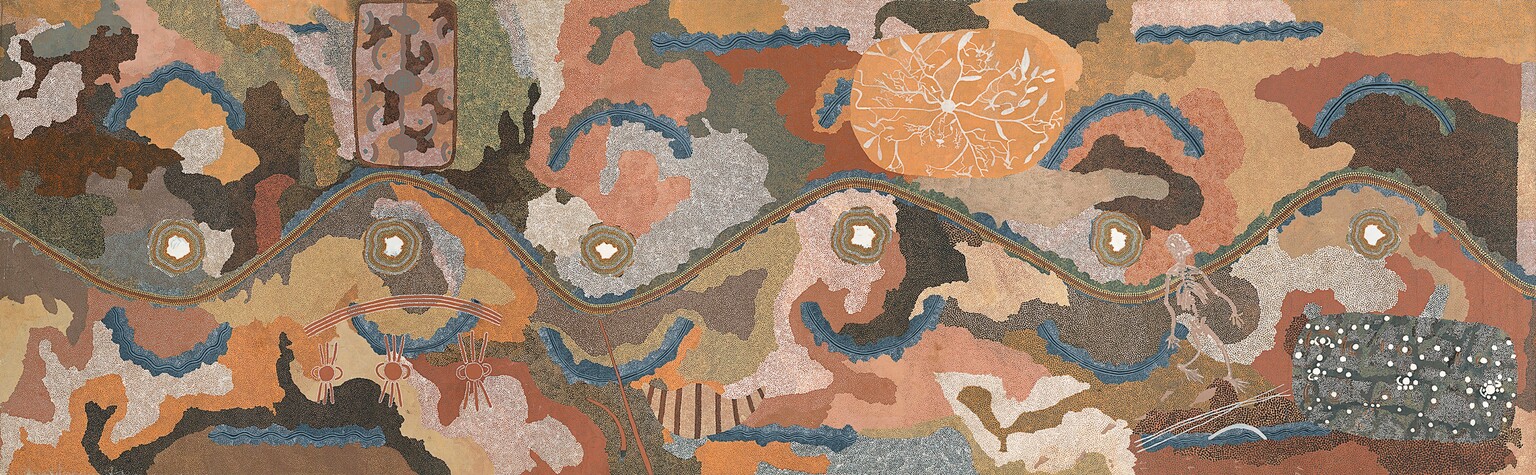

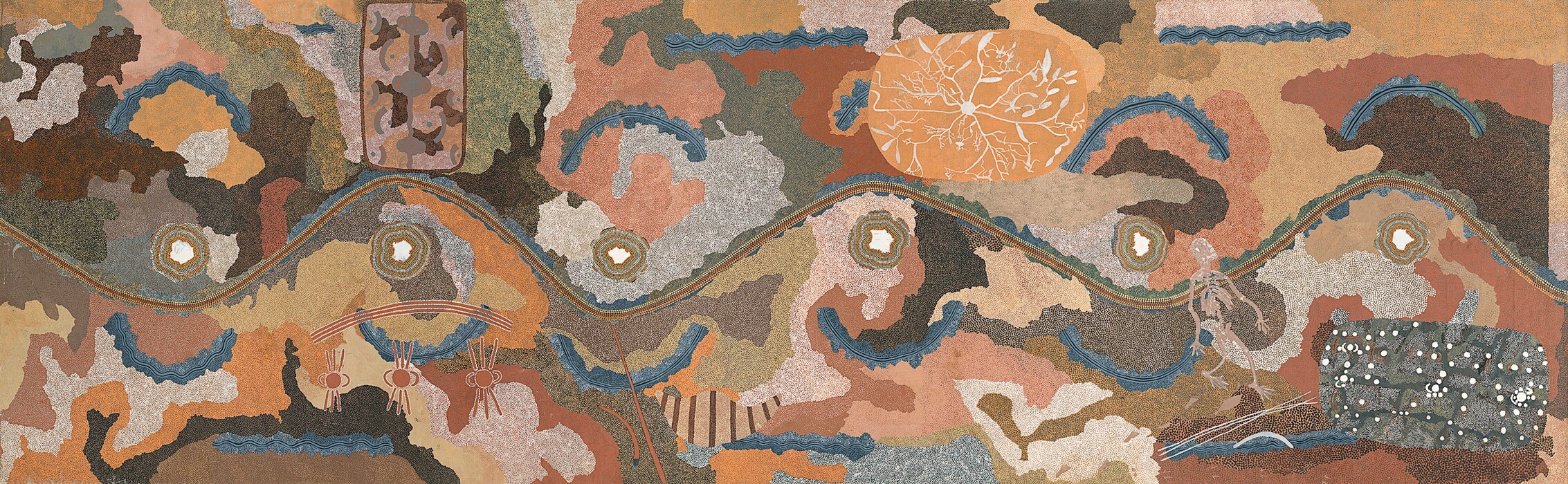

Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (Anmatyerre), Spirit Dreaming through Napperby Country, 1980, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1988. © The artists and their estates 2011, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Limited and Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd. Photo: Predrag Cancar / NGV

For over 65,000 years, Australia has been home to many Indigenous nations who have created art on various surfaces such as rock faces, cave walls, bark shelters, cultural objects, trees, the ground, and the human body. Today, over 2,000 generations since the earliest known human archaeological records, contemporary artists continue to build upon and reinvigorate their Ancestors’ traditions through a range of bold new media.

The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art showcases the extraordinary breadth of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, from the 19th century through to the present day, with over 200 works on display drawn from the collection of Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria. Many of the artists have never exhibited in North America, and some of the works are leaving Australia for the first time—making this show a rare opportunity to experience some of the true masterpieces of Australian Indigenous art.

Prepare for this eye-opening exhibition with an introduction to Australian Indigenous artistic practice through seven standout works.

1. Australian Indigenous art is made by Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders.

Two distinct groups of Indigenous peoples, also referred to as First Nations or First Peoples, live in Australia: Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders. Aboriginal peoples have ancestral roots on what is today known as mainland Australia and in Tasmania. Torres Strait Islanders trace their roots to the archipelago of islands off the northeast coast of Australia, and the bottom of Papua New Guinea.

First Peoples of Australia comprise many distinct groups, each with their own languages, customs, and histories. Prior to the arrival of the British in 1788, there were more than 600 Indigenous nations, representing more than 250 language groups and over 500 dialects. Each language group has a unique language as well as culture and kinship structure.

When the British arrived, they claimed the lands and waterways under the doctrine of terra nullius—the idea that the land belonged to “no one,” despite the obvious presence of both people and culture. This rationalized the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, and resulted in widespread loss of land, culture, and autonomy. Despite this, hundreds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities continue to thrive, demonstrating their strength and resilience.

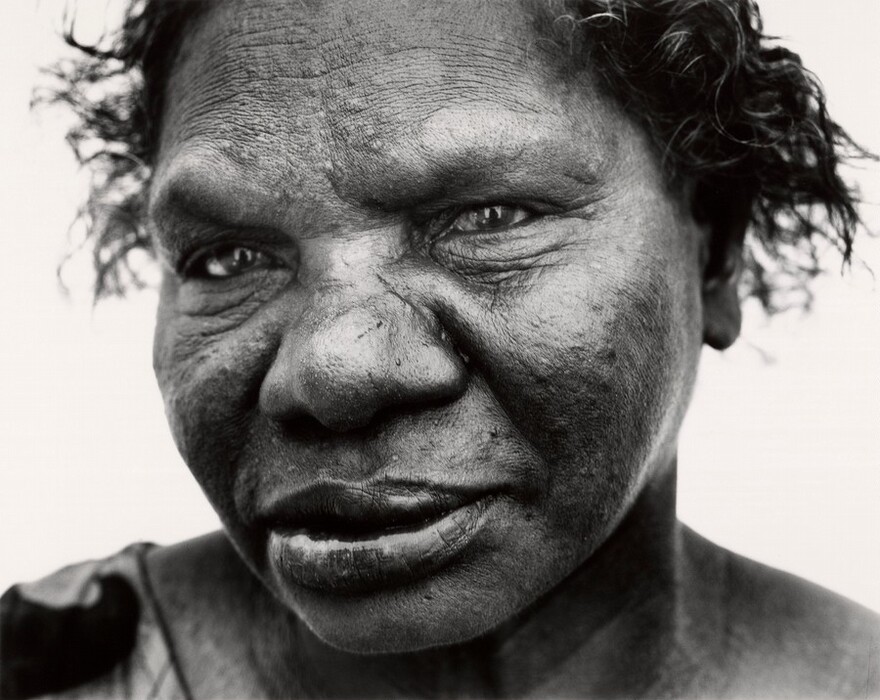

Ricky Maynard (Big River/Ben Lomond), Wik Elder, Gladys, 2000, from the Returning to Places that Name Us series, 2000, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Gift of Milton and Penny Harris, 2007. © Ricky Maynard / Copyright Agency, 2024. Photo: Narelle Wilson / NGV

A common struggle for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today is the ongoing fight for recognition of their legal and moral ownership of their lands. Some Australian Indigenous artists use their work to highlight and advocate for Native Title, the legal notion that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples exercised their own systems of Law and Custodianship of place prior to European arrival.

For his Returning to Places That Name Us series, Ricky Maynard photographed Elders of the Wik people, Traditional Custodians of Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland. One of Maynard’s subjects, activist Gladys Tybingoompa, played a key role in the Wik nation’s efforts to present a Native Title claim to the High Court of Australia in 1993.

2. Indigenous Australian art expresses deep connections to Country.

The concept of Country is central to Australian Indigenous peoples. Country includes not only the physical lands, waterways, and skies of their Ancestral homelands, but also the plant life, Ancestral knowledge, living beings, spirituality, and Laws that are integral to culture. Country is closely tied to personal identity and is also seen as a marker of one’s nation as well as the Ancestral links a person has to place.

Many Indigenous Australian artists express deep connections to Country—through representation of the landscape, depiction of Ancestral stories and designs, use of art materials found on Country, or other creative approaches.

Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (Anmatyerre), Spirit Dreaming through Napperby Country, 1980, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1988. © The artists and their estates 2011, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Limited and Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd. Photo: Predrag Cancar / NGV

Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri were skin brothers, meaning they shared a deep, fraternal bond despite being cousins by blood. As longtime artistic collaborators, their painting Spirit Dreaming through Napperby Country serves as both a self-portrait and a portrait of Country. Each section of the artwork reflects a part of their lives and their profound connection to Country.

The monumental painting references the forced removal of the Anmatyerre people, whose land was overtaken by settlers from the Napperby cattle station in the early 20th century. The enclosed grey, oval shape with white dots in the bottom right corner references an earlier work by the artists, depicting the clouds in the night sky. The skeletal figure to the left is believed to symbolize an old death spirit and is thought to reflect Leura’s growing anguish in the final years of his life.

3. Art that appears abstract often tells complex Ancestral stories.

To the unknowing eye, many paintings by Indigenous Australian artists might at first appear like abstract art. But their fluid forms or dense patterns often represent coded ancestral knowledge, sometimes also referred to as Dreamings. These narratives might recount the formation of a language group’s people and Country, stories of Ancestral and spirit beings, or the kinship structures that make up families.

The Dreaming—sometimes referred to as the Dreamtime, Beforetimes, and the Everywhen—is the foundational era in which Ancestral beings shaped the world, created life, and established the Laws that govern cultural, spiritual, and social practices. Sacred knowledge of Country and Dreamings is often fully shared only with initiated members of a community, meaning that what audiences read is a restricted version of the story. Each work in The Stars We Do Not See was created for public viewing, and while they contain complex cultural knowledge, none of the information presented is considered secret, sacred, or private.

Tiger Palpatja (Pitjantjatjara), Wati Wanampi Tjukurpa, 2010, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased in memory of Graeme Marshall with funds donated by Harriet and Richard England and Anne and Ian McLean, 2011. © Tiger Palpatja / Copyright Agency, 2024. Photo: Jeremy Dillon / NGV

Tiger Palpatja’s paintings tell the Tjukurpa, or Dreaming story, of the creation of Piltati, a sacred place where the artist was born. This canvas reflects the topography of his Country with energetic brushwork and a vibrant color palette. Embedded within his depiction of Piltati’s features—such as rock holes, vegetation, and subterranean depths—is a creation story. Two sisters who grew frustrated with their husband’s lack of assistance with hunting decided to eat the food they had gathered. In retaliation, the men transformed into wanampi (giant water serpents) and went underground. Their wives pursued them, digging into the earth and creating Piltati’s rocky gorge.

4. Dots, lines, and other forms often carry multiple meanings.

This exhibition is named in honor of the late Gulumbu Yunupiŋu, a senior artist belonging to the Yolŋu people of Northeast Arnhem Land. Today known as the "Star Lady," Yunupiŋu dedicated her art to exploring the relationship between the visible and the invisible, the known and the unknowable. Inspired by stories passed down by her father about the creation of the Yolŋu universe, Yunupiŋu developed her own, entirely unique, signature style.

Paintings like Garak (The Universe) feature dense networks of crosses and dots. Each cross represents a star that we can see, and all that is visible within the known universe. The dots symbolize everything in the universe that is unknown: the “stars we do not see,” also called “second stars” by Yolŋu people. Star Lady’s paintings present a cosmos that is entirely full, where everything is connected—even that which remains unknown.

5. Paintings are made on a variety of materials, including bark.

Bark paintings are made commonly throughout the northernmost part of Australia. The practice first emerged as a creative response to European contact at the start of the 20th century, when a British Australian biologist by the name of Baldwin Spencer commissioned artists from Arnhem Land to depict figurative motifs on single sheets of eucalyptus bark. Up until then, these designs had only been painted only on cave walls, bark shelters, the human body, and ceremonial objects, and therefore could not be shared beyond the location of their production.

These first portable paintings catalyzed a movement. Initially, the practice was led by senior Aboriginal men, who held the cultural right to paint sacred themes. By the late 1980s, however, women had also begun to create bark paintings, bringing new approaches that explore materials, color, and design in innovative ways.

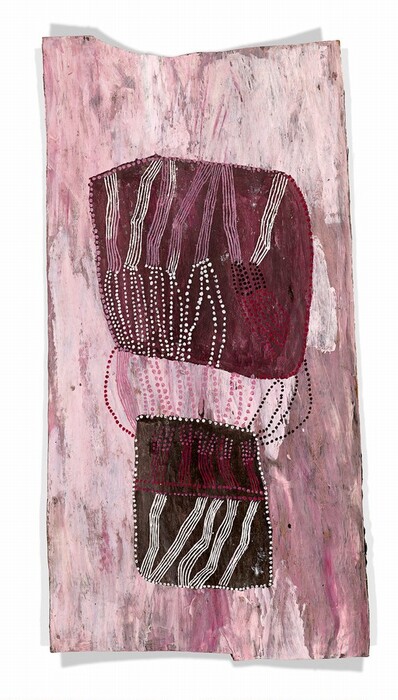

Noŋgirrŋa Marawili (Maḏarrpa), Baratjala, 2019, earth pigments on stringybark, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2021. © The Estate of Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, courtesy of Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala. Photo: Christian Markel / NGV

Bark paintings are typically made from natural ochre pigments on single sheets of stringybark. Artists such as the late Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, however, have radicalized the practice by mixing natural pigments with ink collected from discarded printer cartridges. This innovation has imbued Yolŋu art with an array of brilliant technicolor tones.

This work, Baratjala, represents a place in the Maḏarrpa clan’s coastal estate that borders the Gulf of Carpentaria. Embedded within the rock floating in the center of the composition is the energy of the artist’s father, Mundukul, who is also the lightning snake. White dots and zigzag lines illustrate the buildup of electricity in the clouds during the monsoon season.

6. Australian Indigenous Art includes the longest weaving traditions in the world.

For millennia, women throughout Australia have collected local grasses, plants, and tree leaves to use as raw materials in their weaving practice. Woven objects can have both spiritual significance and a utilitarian function. The natural materials are generally hand-spun into what is known as bush string, which is dyed and then looped, knotted, coiled, or woven to create fiber baskets, fishing nets, string bags, mats, and various other functional and decorative objects.

Freda Ali, Freda Wayartja Ali, Maureen Ali, Cecille Baker, Michelle Baker, Bonnie Burarngarra, Gabriella Garrimara, Doreen Jinggarrabarra, Lorna Jin-Gubarrangunyja, Indra Prudence, Jennifer Prudence, Zoe Prudence, Anthea Stewart (all Burarra-Martay), Mun-Dirra (Maningrida Fish Fence), 2023, pandanus, kurrajong, bush cane, jungle vine, natural dyes, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with funds donated by Lisa Fox, 2023. © The Artists / Copyright Agency, 2024. Photo: Predrag Cancar / NGV

The community of Maningrida, in West Arnhem Land, has long been home to a rich and vibrant weaving tradition. Grandmothers, mothers, and daughters, come together to weave collaboratively, as a way of passing down matrilineal knowledge across generations. In 2021, a group of senior artists from Maningrida worked together to produce this immense installation, Mun-Dirra, also known as the Maningrida Fish Fence.

Made of ten panels, the entire installation is over 330 feet long and is based on a traditional fish trap used by women and men for hunting. Each panel, with its unique interlacing design and colors, reflects the individual style of its maker. The different sections of Mun-Dirra overlap to create a unified installation, bringing together land and sea while highlighting the power of Aboriginal women’s collaboration.

7. Australian Indigenous art illustrates the resilience and creativity of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders.

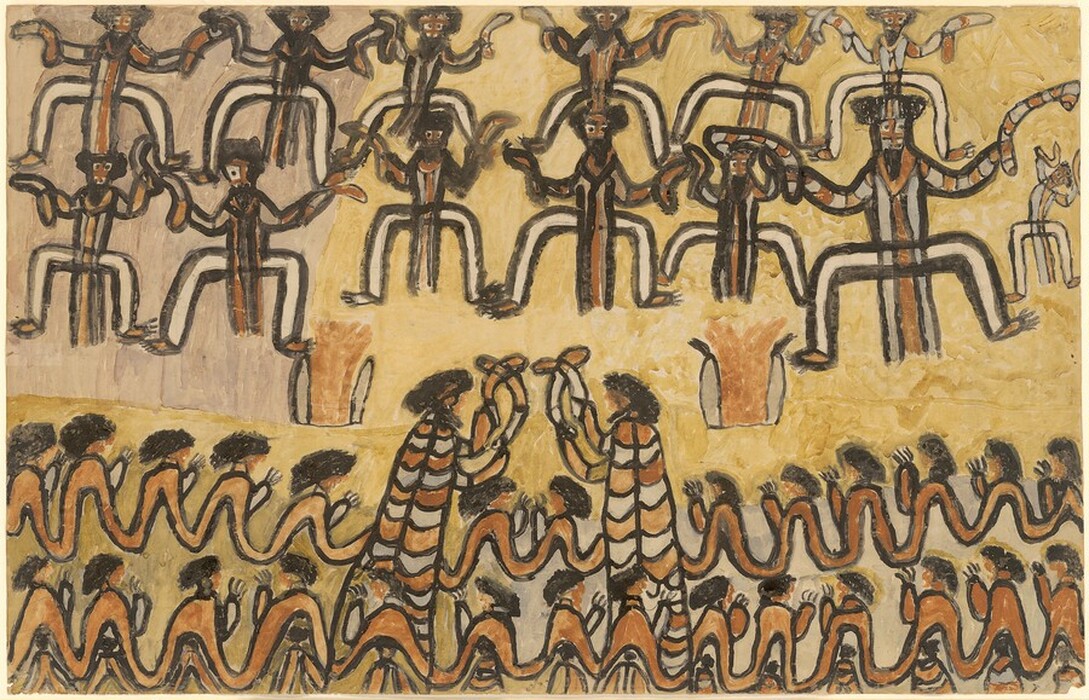

William Barak, also known as Beruk, witnessed several attempts by settlers to eliminate his people. During his lifetime (1823–1903), the Aboriginal population decreased by nearly 90 percent as a direct result of colonization, primarily due to smallpox, forced dispossession, and massacre.

Barak became a determined leader of the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people, fighting for the rights of his people and others. His painting Ceremony is one of the earliest works in the exhibition. It depicts men, women, and children dressed in ceremonial attire, primarily possum skin cloaks and dance belts.

The men raise their hands, holding boomerangs that are used musically as clapping sticks. Their legs are positioned at right angles in dance, while the figures in the foreground, including the women, appear to be watching.

The exact details of the ceremony are unknown; however, at the time this work was produced, conducting ceremonies was strictly forbidden. As a result, Barak’s work has become a treasured reliquary of a culture that has survived for thousands of years.

William Barak (Wurundjeri), Ceremony, 1898, pencil, wash, ground wash, charcoal solution, gouache, and earth pigments on paper, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased, 1962. Photo: Garry Sommerfeld / NGV

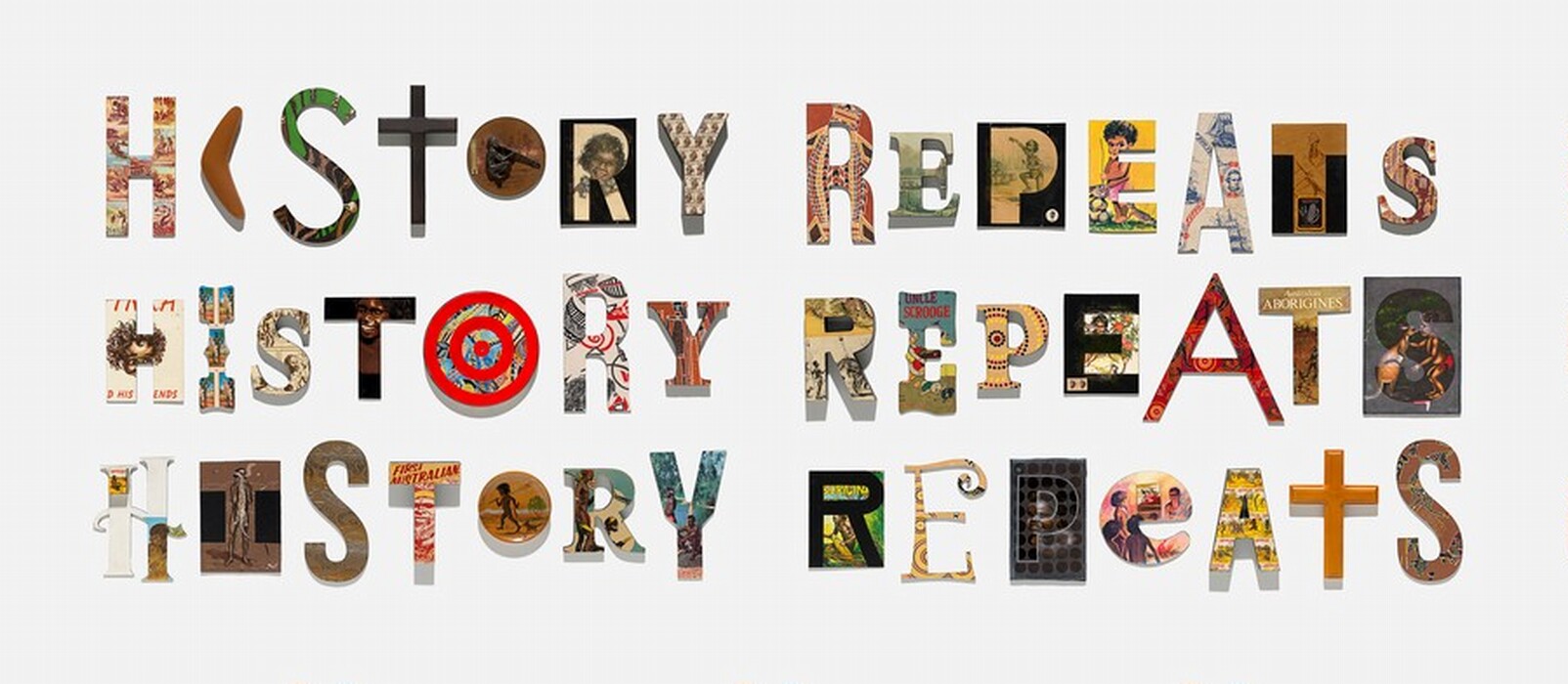

Made nearly 125 years later, Tony Albert’s History Repeats examines the impacts of British colonization. The work is made from what the artist calls “Aboriginalia”—found objects that use Indigenous iconography as decoration. Albert encourages us to look at history and consider the ways in which trauma of the past can manifest in the present. His work is also a reference to Indigenous concepts of cyclical time, wherein the past and future actively affect our lives in the present.

Australian Indigenous art draws on this connection to time, Country, and Ancestral traditions. Artists like Albert continue to find new forms of expression that engage with contemporary society while also acknowledging tradition, past, present and future. As Yolŋu educator Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr-Stubbs says, “The time of the past is the time of now and the time of the future.”

Tony Albert (Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku Yalanji), History Repeats, 2022, found vintage kitsch objects and timber, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased with funds donated by Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM and Family, James Farmer and Rutti Loh, Nicholas Smith, The JTM Foundation and Donors to the 2023 First Nations Art Dinner, 2023. © Courtesy of the Artist & Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney. Photo: Predrag Cancar / NGV

Exhibition : The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art

Don’t miss this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art—the largest ever shown outside Australia. Opening October 18.

You may also like

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Article: George Morrison Gets His Due

The Minnesota painter merged abstract expressionism with traditional Ojibwe values.