Centering Asian Artists in the American Story

Asian Americans are often left out of view of US history. But their lives—and their art—are an essential part of the nation’s story. See how Asian American artists have interpreted pivotal events of the past 100 years.

Ruth Asawa and Her Family Endure Japanese Internment

Ruth Asawa grew up on a farm in the greater Los Angeles area. She was 16 years old in 1942, when FBI agents seized her father Umakichi Asawa. They separated him from his family and forcibly relocated him to a labor camp in New Mexico. He had lived in the United States for 40 years. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 allowed authorities to round up and confine anyone of Japanese descent, regardless of their citizenship. Asawa did not reunite with her father until 1948, six years later.

Just a few months after her father’s arrest, Asawa was also detained with her mother and five of her six siblings. They were held at the racetracks-turned-internment camp in Santa Anita, California. Disney animators Chris Ishii, Tom Okamoto, and James Tanaka were also imprisoned there. They held art classes for their fellow internees, and it was there that Asawa began to take drawing seriously.

Ruth Asawa, Japanese American Internment Memorial (PC.011), 1990-1994. Bas-relief bronze for the City of San José Public Art Program. Photographer: Hunter Ridenour (2022). Artwork © 2024 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy David Zwirner

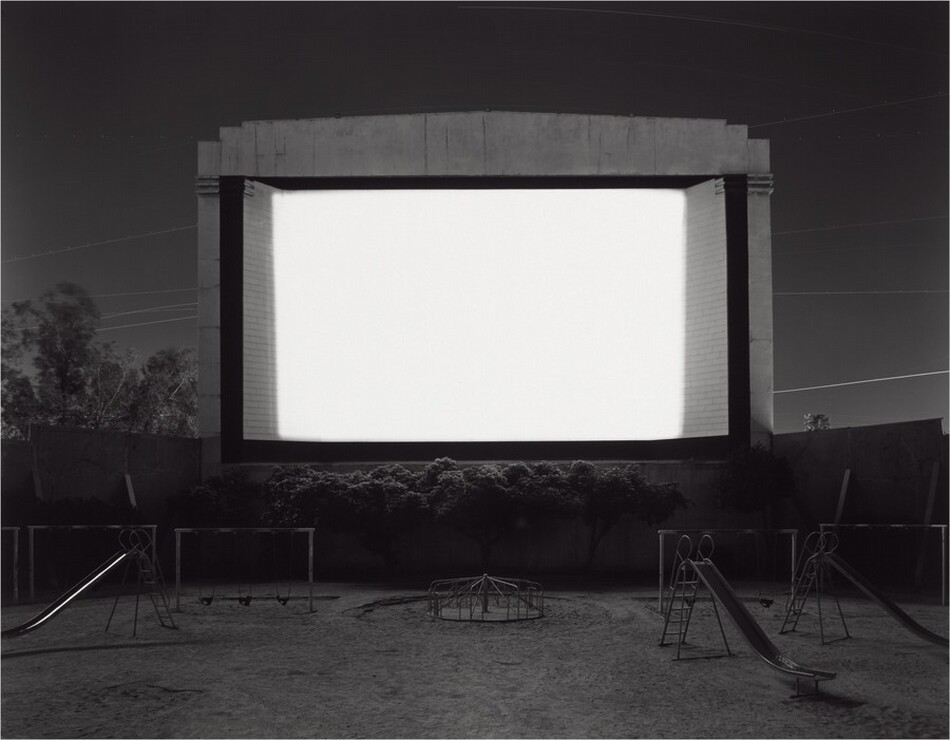

Asawa became famous for her airy wire sculptures, but that didn’t stop her from working in a weighty bronze to memorialize her experiences and those of fellow Japanese internees. With help from her son Paul Lanier and friend Nancy Thompson, she designed and cast the Japanese American Internment Memorial outside the Federal Building in San Jose, CA, dedicated in 1994.

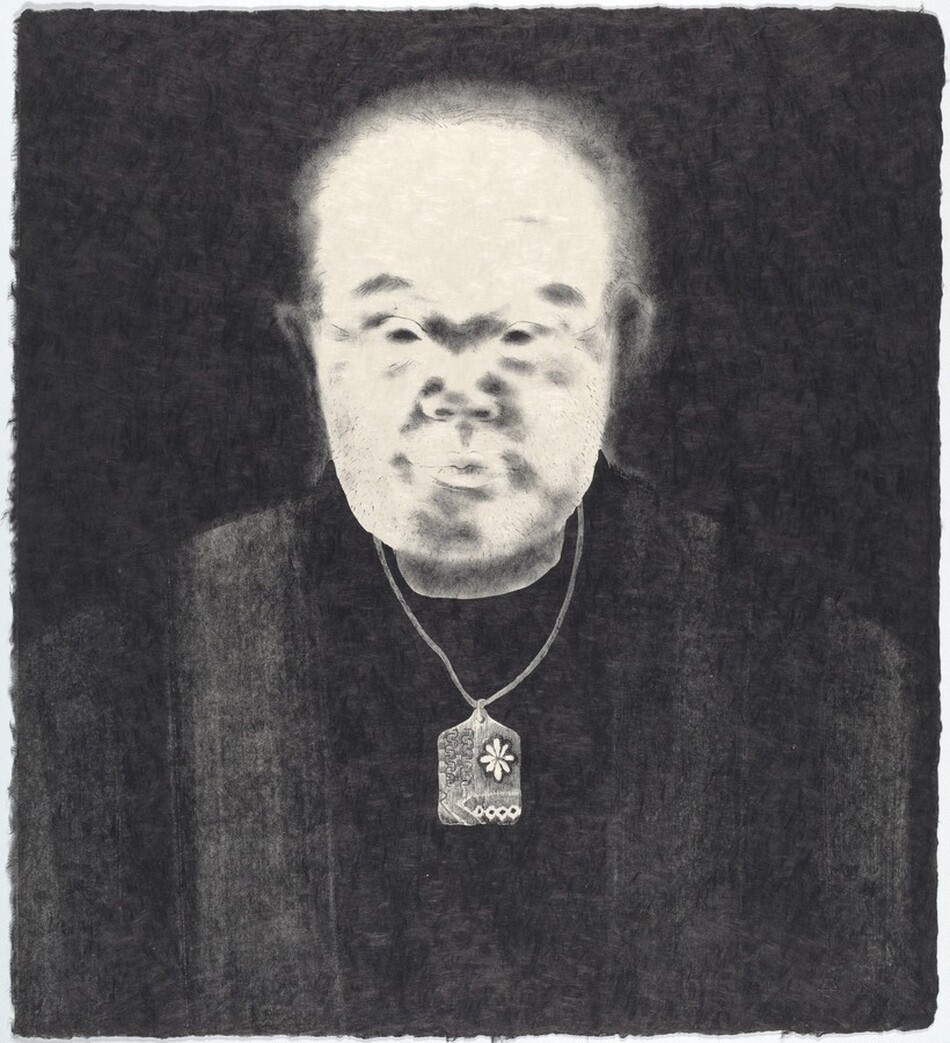

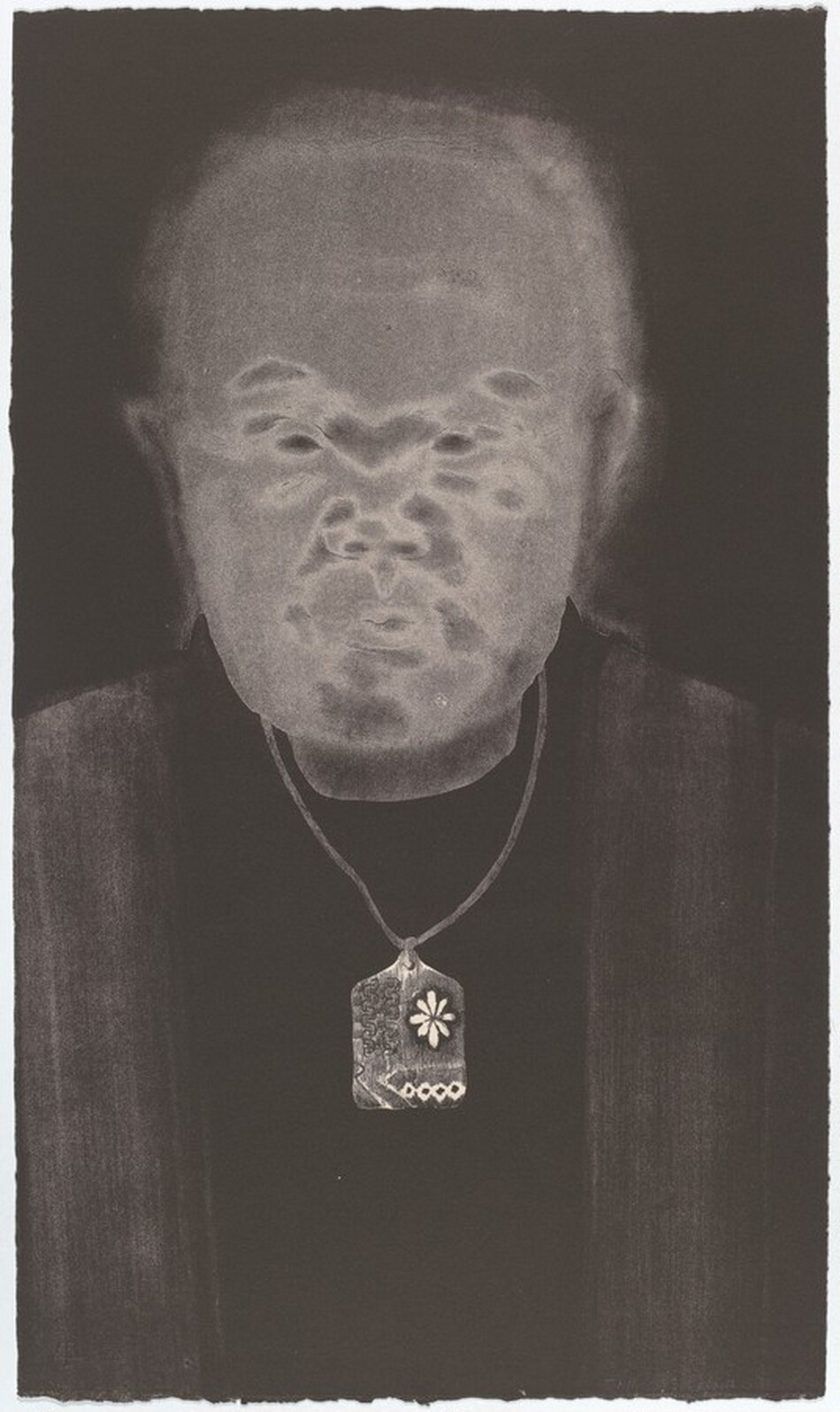

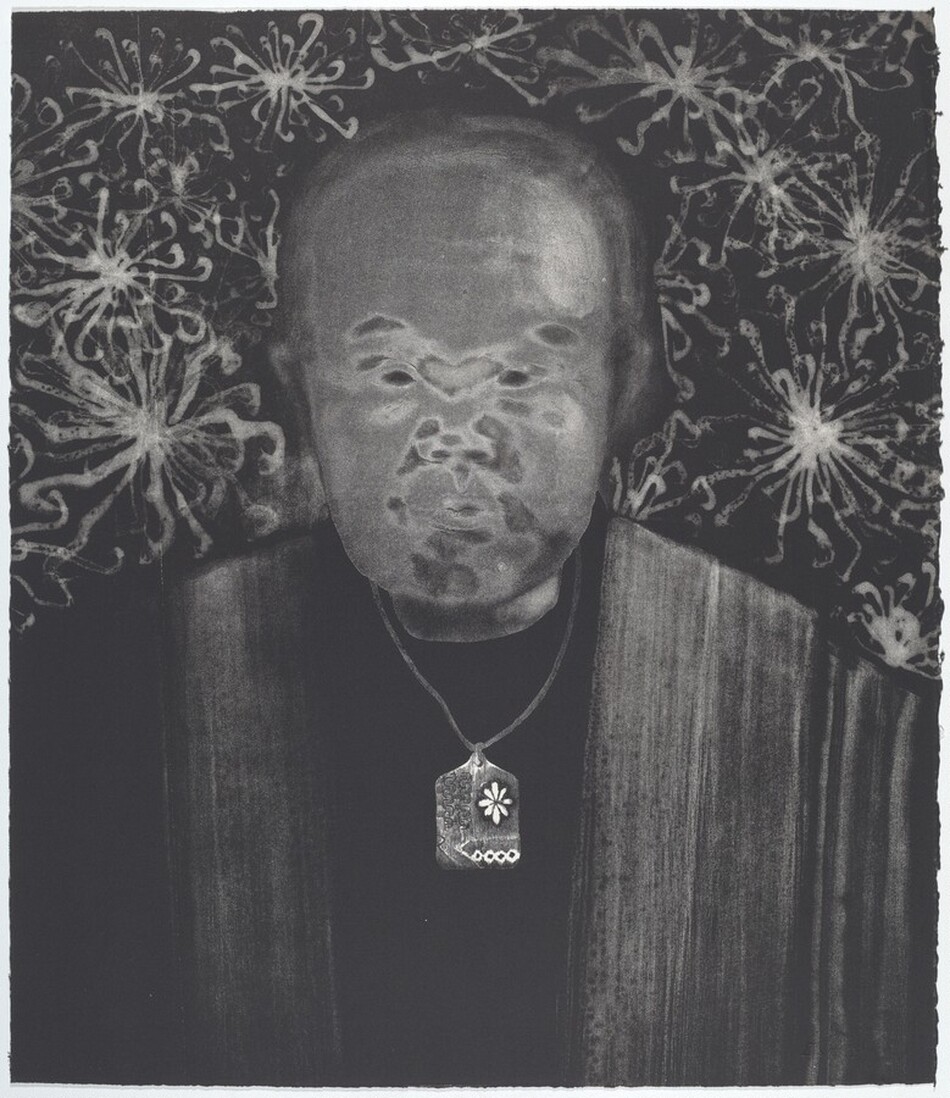

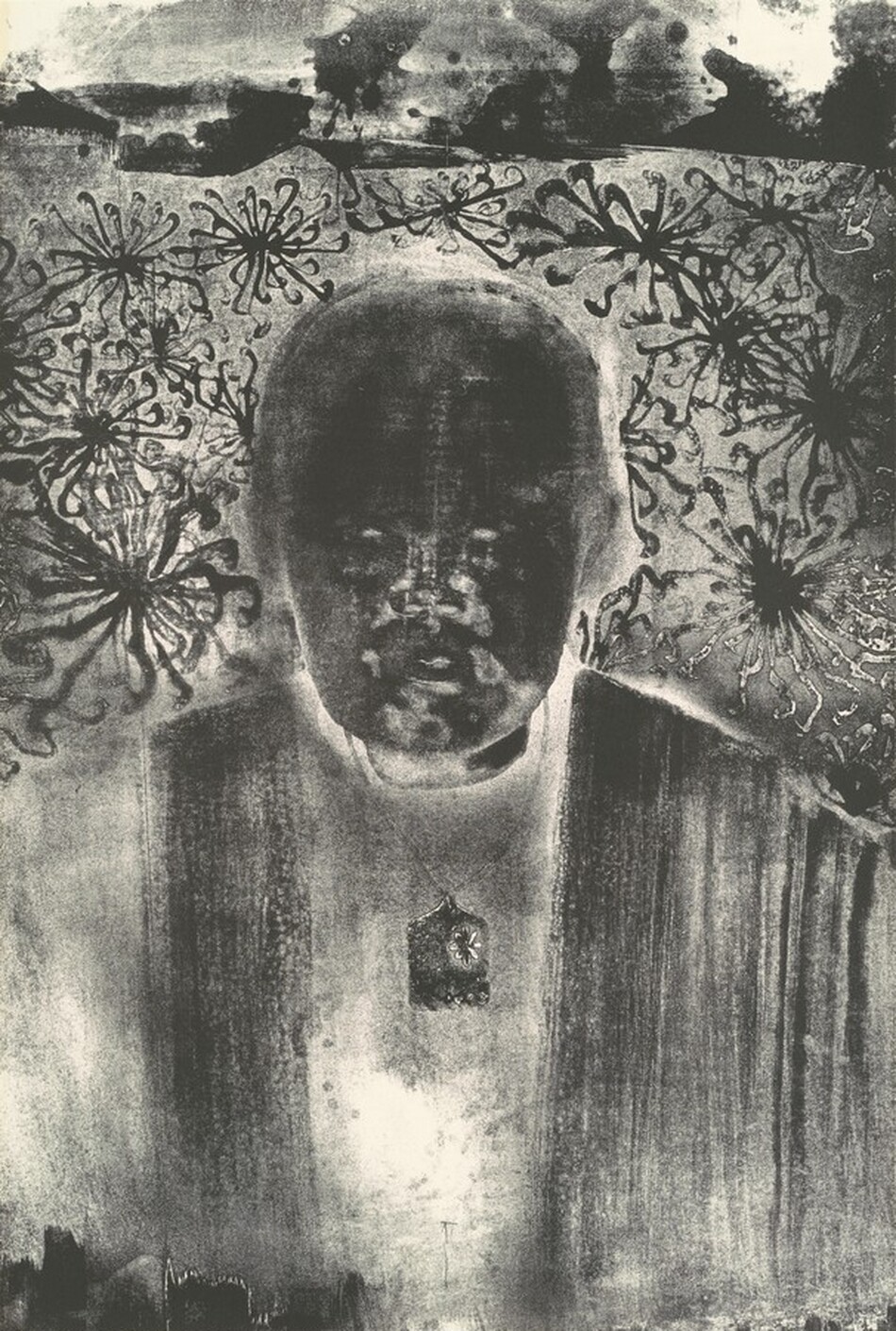

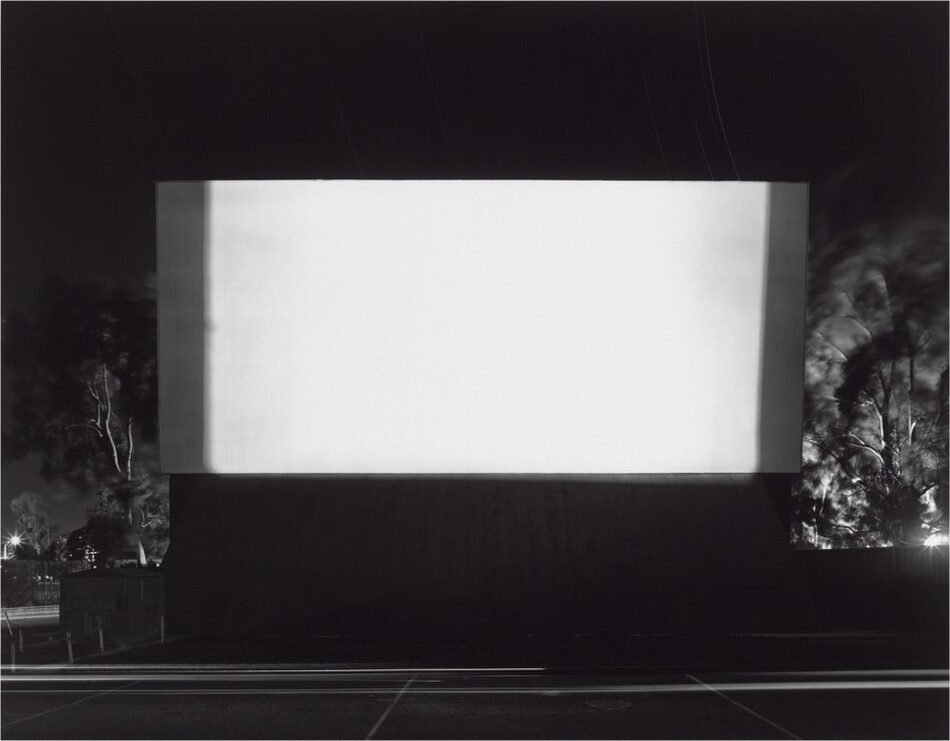

During her residency at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in 1965, Asawa made a series of four lithographs commemorating her father. In them, Umakichi looks straight as us with a relaxed, slight smile. Asawa casts his face in light and shadow, and in one print, even plunges him into a ghostly negative. The images are filled with a sense of distance and longing.

Artist's Experiences of Internment

Artist's Experiences of Internment

Binh Danh Remembers the Vietnam War

Binh Danh’s family fled war-torn Vietnam when he was just two years old. They arrived by boat as refugees in the United States in 1979.

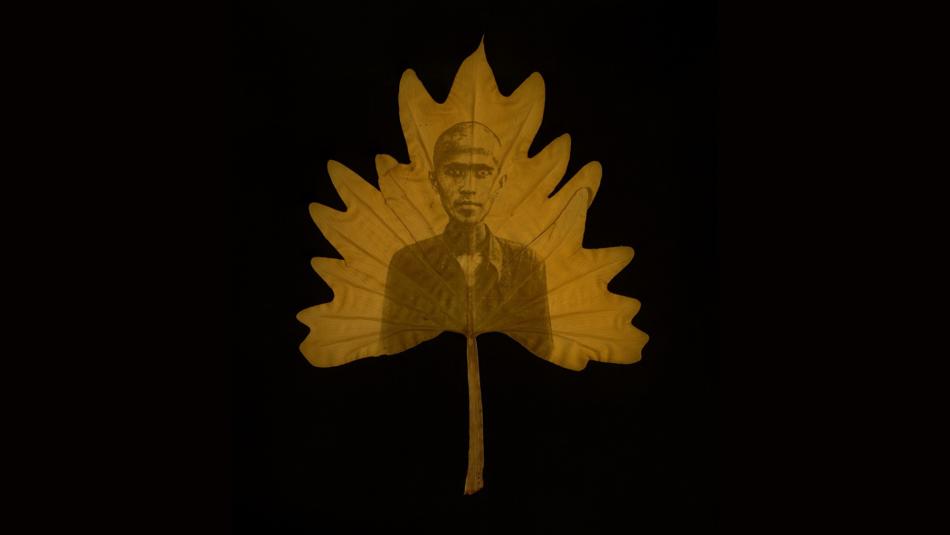

After returning from his first visit back to Vietnam in 1999, Danh began to print photographic images onto leaves using a printing process he invented. He placed transparent negatives of mass media photographs of the Vietnam War onto living leaves. He then left them in direct sunlight. This allowed the sun to “print” the images into the leaves through photosynthesis.

These chlorophyll prints, as Danh calls them, featured both American soldiers and Vietnamese people affected by the war. He explains,

That history is not talked about in the family because it’s so painful. People in the United States wanted to forget because it was a war that Americans didn’t win. But for my parents’ generation it was a war they lost.

His subjects also included victims of the Cambodian genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge regime. During the Vietnam War, the US military dropped an estimated 500,000 tons of bombs on Cambodia. This killed over 150,000 civilians and contributed to the rise of the Khmer Rouge. Danh’s own father was born in Cambodia, and the artist’s identity is shaped by the two countries' intertwined histories.

After a subsequent visit to his father's birthplace in Cambodia, Danh printed some of the photographs taken of prisoners at Tuol Sleng. At this brutal prison run by the Khmer Rouge, 14,000 Cambodians were tortured and sentenced to death.

Danh’s haunting photographs bear witness to history, and his art offers a different way to remember victims of war and genocide — not as an uncountable many, but as individuals. He calls these works altars to the dead, “a place where we can meditate on history, the present moment, and our own mortality.”

Meet other artists whose works respond to US involvement in the Vietnam War.

Meet other artists whose works respond to US involvement in the Vietnam War.

Nam June Paik Predicted the Digital Age

Born in Seoul in 1932, Nam June Paik grew up during Japanese occupation and World War II. He viewed television and other broadcast mediums that transmitted information one way as dictatorial. In his work, Paik aimed to undercut the power imbalance of broadcasts. By distorting video feeds, the artist showed his audiences the manipulation behind the images and offered a model for how television might be made more democratic and even revolutionary.

Around the time that he arrived in the US in 1964, Paik began experimenting with using television monitors in his art. At first, these works were criticized as shallow and commercial. Viewers could not understand why they were looking at TVs when they had come to see art. But in writer Hua Hsu’s words, “His art was always about a present that had yet to come into focus for everyone else.” Paik is now known as the father of video art.

In 2005, the year before his death, Paik created Ommah (“mother” in Korean). His last work of video sculpture, it sums up his wide-spanning career. A traditional Korean robe made of lightweight silk hangs in front of an LCD TV monitor. The television flickers between footage of three Korean American girls in traditional costume dancing and playing together, close-up views of early video games, clips from TV shows, and samples from Paik’s earlier videos. The video loop is distorted twice: it is manipulated using a video synthesizer, and we view it through the translucent silk robe.

Ommah captures the feeling of living through the era of digital overload, in which we never stop watching each other and ourselves. It's a fitting look back for the artist who presciently coined the term "electronic super highway" in 1974 to describe the media technologies that would transform our society. As Paik put it, technology is “progressing rapidly—too rapidly.”

Another Artist Exploring the Media

Another Artist Exploring the Media

Maya Lin Confronts Rising Sea Levels

Chinese American sculptor Maya Lin rose to fame in 1981, when she was 21 years old. She won a national contest to design a memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC, honoring those who died fighting in the Vietnam War. She was still an architecture student at Yale University—and she beat her own professor in the contest. When the winning entry was revealed, Lin’s gender and age sparked immediate backlash.

Over the past few decades, Lin has shifted her focus to the environment. To Lin, climate change is the existential challenge of our time. She works on both monumental scales—such as that of the Columbia River Confluence Project—and in more intimate forms.

Lin made Latitude New York City in 2013, a year after Hurricane Sandy brought nearly 8 feet of flood waters to lower Manhattan. The sculpture traces the rising sea levels that threaten the city. To create Latitude New York City, she used computer modeling to map the physical terrain along the east-to-west latitudinal line between the 40th and 41st parallels, which passes through Manhattan. The topographical model shows where the surface descends into the depths of the ocean floor. Lin carved the map into a marble ring.

Lin emphasized that the existing boundaries between land and water could not be taken for granted in an era of severe climate catastrophe. Her work conveys the urgency of the crisis. Of herself, she demands,

You may also like

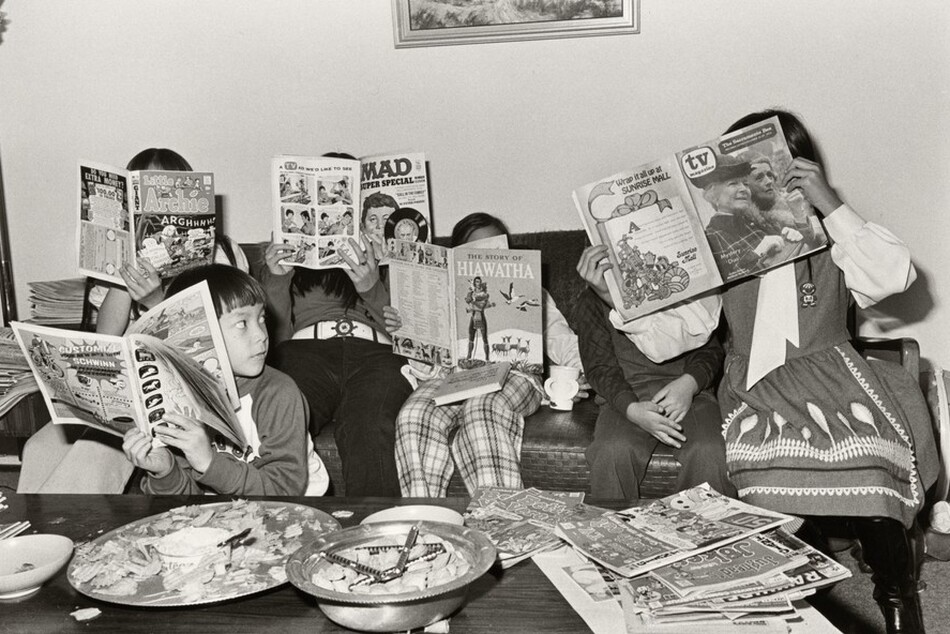

Article: 12 Documentary Photographers Who Changed the Way We See the World

Photographers of the 1970s revolutionized the medium through innovations of both style and subject.

Article: Poet Victoria Chang Responds to a Sculpture by Anne Truitt

The poet responds to a sculpture by Anne Truitt and asks the questions “Who gets to speak, who gets to brush.”