Lindsay Adams’s Intimate Paintings Explore Place, the Self, and Memory

We invited Jasmin Hernandez, founder and editor in chief of Gallery Gurls, to spotlight a living artist who takes inspiration from our collection.

Lindsay Adams’s oil paintings, of both flora and people are intimate, introspective, and quietly beautiful. Across her soulful paintings, Adams says she is “working to capture the nuance and depth of both humanhood and personal and shared histories. In many ways my figures represent an extension of myself.”

In Adams’s elegant, meditative pieces, she investigates race and representation. While grappling with her personal feelings of otherness and exclusion, the young artist presents Black subjects with emotional depth and range.

Her subjects make direct eye contact with the viewer. They usually hold everyday objects, like pieces of fruit or bouquets of flowers. She paints them with “a specific intimate gaze, with both vulnerability and strength.”

Adams uses a gestural painting approach. When painting her subjects, she places them on a thin layer of paint on the canvas. Adams then layers on paint, moving between slow and rapid brushwork, which feels therapeutic and rhythmic. Adams, who’s also a writer, titles her oil canvases and works on paper with a very poetic and literary tilt.

The artist is currently based in Chicago, pursuing an MFA in painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. But she is very active in the DMV area, her home. (Adams was born in DC, and grew up in Prince George’s County, Maryland.) In 2022 her solo show Two Things Can Be True debuted at Eaton DC. The same year, she exhibited at the Martin Luther King Memorial Library in DC, among other cultural spaces. This year, the Baltimore Museum of Art acquired and showed her very moving floral canvas, Down at the Cross.

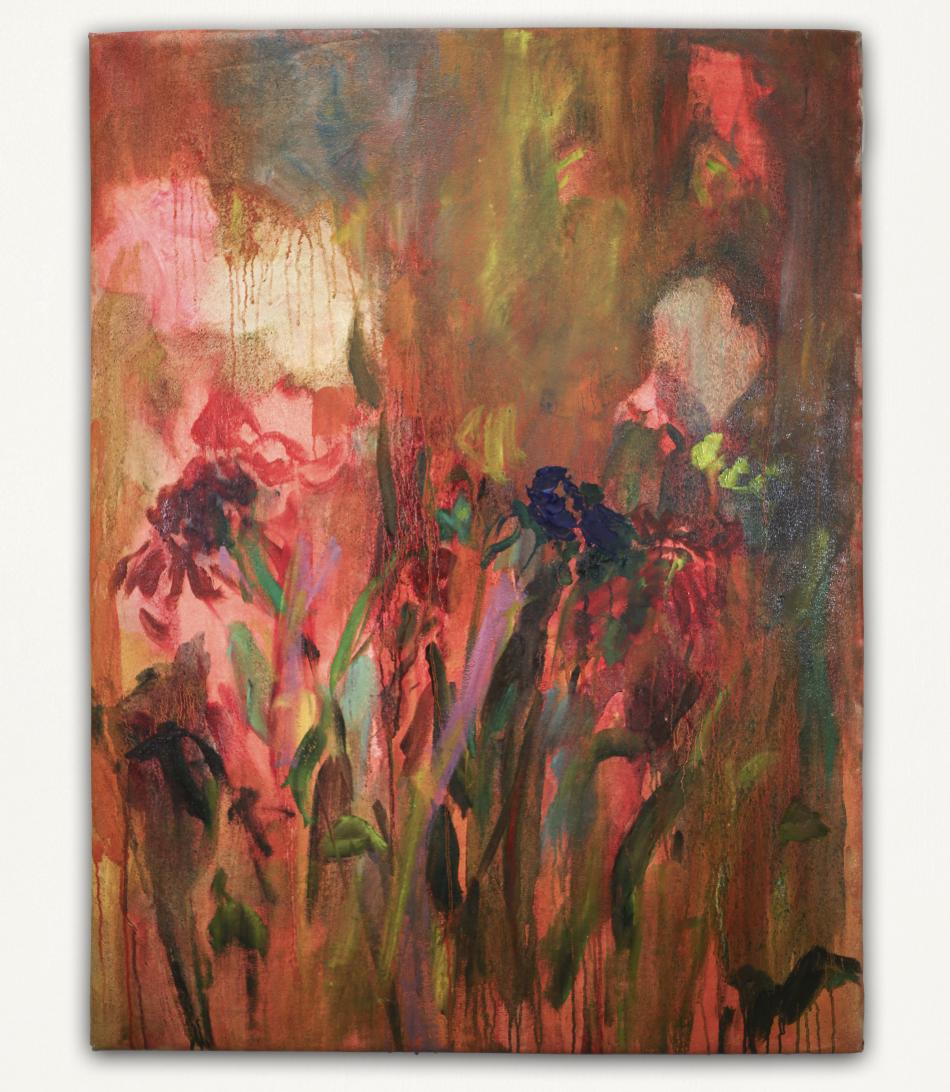

Lindsay Adams, Power of The Things Unseen, 2023, oil on linen, courtesy of artist

Florals and Black Ancestral Connections

Adams is a Black American woman artist living with cerebral palsy (CP). Her floral pieces serve as a portal to her selfhood. She has explained that the flora serves "as subject and the visual foundation of the work, while the content is a deeper conversation with myself." The different flowers represent not only various aspects of Adams’s identity but also the many ways in which she is marginalized. These include ableism, misogynoir (sexism and racism against Black women), colorism (prejudice against people with darker skin tones, often within the same racial group), and other forms of oppression. But Adams is also a disabled person with invisible conditions. She only has to speak about CP, her speech impediment, and her premature birth when asked—and she knows that there is privilege within that. Her electrifying canvas Power of The Things Unseen shows a vibrant array of flowers. Their layered petals symbolize Adams’s multiple selves, which aren’t always visible as she navigates life.

Her floral paintings are also connected to the broader Black experience. That is why she’s decided not to assign them genres such as still lifes or landscapes. In her own words, “The florals represent a personal interrogation and reflection on the Black ancestral connection to land, place, and home.” For Adams, every floral canvas or work on paper is singular, with its own story to tell. There’s no one way to be Black, and Black people expand cultures and build communities continually, in many ways.

In The Sun in the Mourning, the rich shades of the flowers—scarlet, hot pink, and burnt orange—feel tender and warm. As the title suggests, you could imagine this floral bouquet sitting by the windowsill as the morning sunlight shines through. But there’s also a heavier, much darker feeling behind this work. We are often given flowers in times of grief and sadness. Adams emphasized this double meaning in the work and its title. The painting seems to have an almost oxidized effect, and that carries a deep melancholy. According to the artist, “Flowers have many different layers to their meaning . . . celebration, mourning, becoming, beauty, and decay.”

Place, Space, and Memory

While attending homecoming at her undergraduate alma mater, the University of Richmond, in 2018 Adams saw Howardena Pindell’s work for the first time. It was the artist’s first major traveling retrospective, Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Adams and Pindell both use autobiographical content to unpack race, misogynoir, memory, and Black womanhood. Adams describes her connection to Pindell: “I’ve seen many parallels with my life and hers: her time at an all-girls school; continuing onto a predominately white liberal arts university; and navigating these spaces socially, politically, and artistically.”

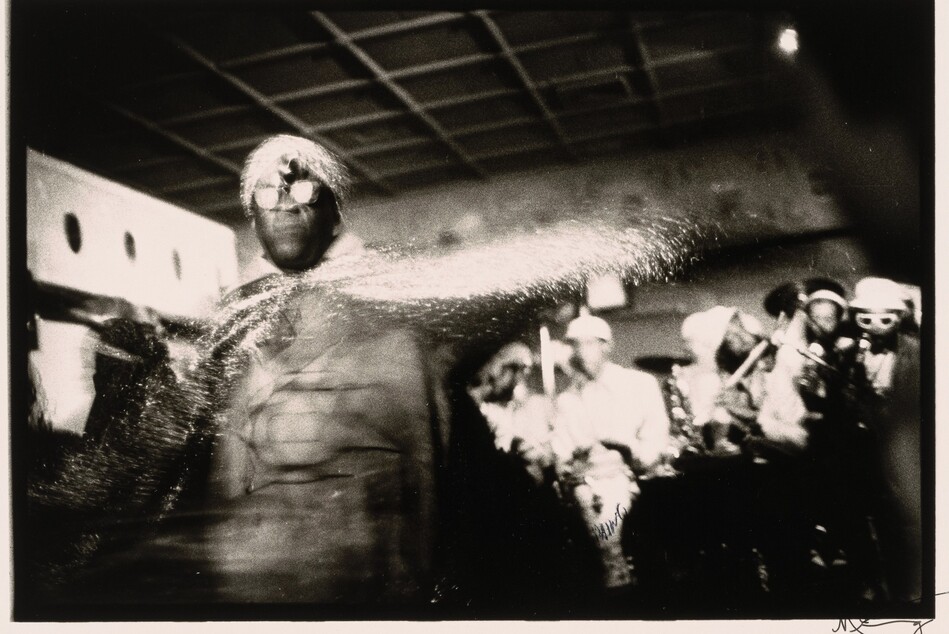

In the early 1980s, Pindell spent seven months living in Japan on a National Endowment for the Arts grant for a US-Japan artists exchange. She was heavily influenced by Kabuki theatre costumes and the use of color in Japanese fabrics. She also faced sexism, racism, and xenophobia during her time there. And these experiences all show up in her work.

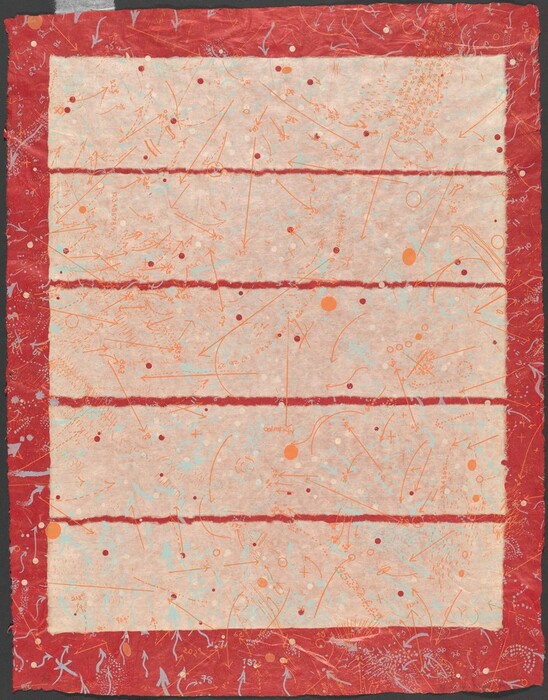

Kyoto: Positive/Negative is a combined etching and lithograph printed on various Japanese papers. A persimmon red border surrounds a pale rose background. The work is scattered with Pindell’s signature hole-punched dots.

Pindell likely experienced both beautiful and ugly, positive and negative moments in Japan. In this abstract piece, she used texture and space to lay out her memories of a specific place and her emotions about her jarring social interactions there. This resonates with Adams, who is “also mending, putting together fragments of memory and place” and processing the “sometimes painful aspects of remembering.” She adds that “space, place, and land can be quite contentious, especially as we think of who owns it and who has access to it.”

In Adams’s abstract floral work, Where Can I Go To Frolic? (from a recent series of the same name), she layers wine reds and dark purples with text. Frolicking, as Adams sees it, stands for “a sense of freedom and liberty,” a break from labor, exhaustion, even late-stage capitalism. Adams raises a fundamental question about where Black and Indigenous folks (and other peoples who make up the global majority) can access, own, and experience deep joy. This is especially significant because these are the people whose work keeps wealthy nations running.

Lindsay Adams, Where Can I Go To Frolic? (02), 2023, oil on canvas, courtesy of artist

The Personal and the Shared

“Libraries are where I ran into the least prejudice, the art world is the opposite,” Pindell once said. She was not only an artist but also a curator. And she faced constant frustrations within white feminist art circles in New York City. She cofounded the all-women A.I.R. Gallery in SoHo in 1972. But when she brought up race, the white women around her dismissed her as too “political.”

But the year between 1979 and 1980 was especially transformative for her. In 1979, white artist Donald Newman exhibited The N***** Drawings at Artists Space. Pindell and her peers (such as Faith Ringgold and Linda Goode Bryant), protested the racially violent exhibition.

That same year, she left the MoMA after 12 years as its first ever Black (and Black woman) curator. Pindell has said that she faced misogynoir and tokenism at MoMA and was undervalued. She then took a teaching job at Stony Brook University in Long Island. Soon after, she survived a near-fatal car crash while commuting to work; it left her with amnesia.

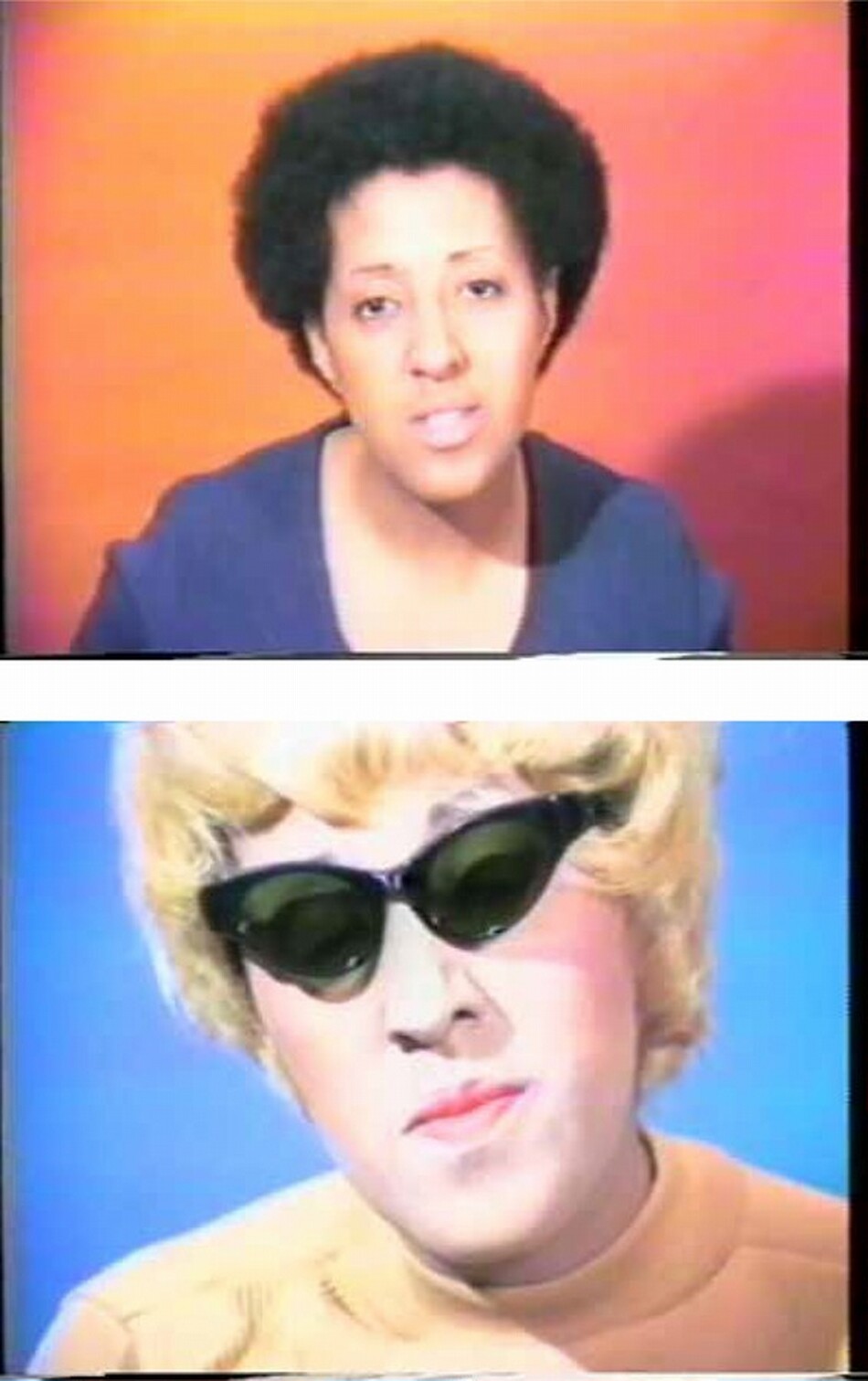

Working through this difficult time, Pindell created her groundbreaking short film Free, White and 21 just eight months after her accident. In the 12-minute film, Pindell describes several racist incidents. She also wears a blond wig and whiteface to play a white woman. The white character gaslights Pindell at every turn, responding to her stories with snarky replies, such as, “You really must be paranoid.” Free, White and 21 is still incredibly relevant. For Adams, it “represents both the personal and the shared”—viewers who’ve faced sexism, racism or both can identify with Pindell’s lived experiences. She considers the film, “vulnerable and intellectual” and explains that it “brings viewers into a deeper, historically ignored conversation.”

While Pindell and Adams are from different generations, their work addresses similar struggles, Adams says, “as it relates to Blackness and womanhood.” They also have disability in common, as Pindell, now 80, uses a wheelchair. There is a through line from Free, White and 21 to Adams’s oil portrait Not on My Watch. The Black woman in this painting offers a watchful gaze. The weight of her stare carries agency, defiance, and a knowledge of the obstacles unique to us, Black women.

Pindell has been an abstract and conceptual artist, filmmaker, and professor for nearly six decades. Her impact is especially monumental for Black women artists and art workers. Adams still recalls Pindell’s retrospective in Richmond. “To experience a major survey of work by a Black woman in the former capital of the Confederacy was . . . remarkable . . . in itself,” she explains.

Adams’s gorgeous and haunting figurative and flora paintings are an ode to Blackness and the endless ways we exist. Adams holds a reverence and a sacredness for herself, her inner layers, and her subjects. She says, “I’m also creating this place of home and memorial within the works.”

Banner image: Artist Lindsay Adams in her studio. Photograph by Mary Pistorius, courtesy of the artist.

You may also like

Article: Bianca Nemelc Paints the Spiritual Bonds Between Womanhood and Nature

The New York–based Latina artist finds deep connections between rest, nature, and womanhood in her vibrant paintings.

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.